Although largely forgotten today, rickets was once one of the most devastating diseases in the developed world: in poor urban neighborhoods, up to 90 percent of the children showed characteristic symptoms, including bent spines and bowed legs. The disorder was especially hard on women, since it flattened their hip bones and, in later adulthood, made childbirth far more dangerous. The search for the cause of rickets took decades and ended with a startling discovery: that much like plants, human beings had the ability to photosynthesize.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

Over and over, the lion cubs kept dying. It was London, the 1880s. The lioness in the London Zoo had produced twenty litters over a dozen years. But she could never make enough milk. And as soon as the cubs were weaned and moved on to a diet of goat meat, they started suffering.

Their limbs bowed out, and their spines sagged. One two-month-old cub proved especially sad. She was emaciated and half-paralyzed; she couldn’t run after her playmates without staggering and falling. She also suffered from seizures and died at just three months old.

And she was hardly alone. In 19 of the 20 litters, every single lion cub died.

When yet another litter was on the verge of death, the desperate zookeepers turned to a young surgeon for help. Dr. John Bland-Sutton moonlighted at the Zoo dissecting animals for his research into comparative anatomy. In examining the dead lion cubs, he found that they had soft bones—a disease called rickets.

The zookeepers asked Bland-Sutton how to fix the problem. After thinking things over, he blamed the lean goat meat that the cubs ate. He suggested switching to fattier horse meat. He also suggested adding ground-up bones and milk. On a whim, he told the keepers to add cod-liver oil as well. It couldn’t hurt.

The zookeepers tried the new diet on the ailing cubs, then spent weeks pacing and fretting. But they need not have worried. The cubs thrived on the food, practically springing up from the dead. Within a month, they were scampering around like Simba, play-fighting and sounding mini-roars. After that, the Zoo never had a problem with rickets again.

The story of Bland-Sutton’s miracle cure quickly circulated among doctors in Europe. That’s because rickets wasn’t just a disease of lions—humans suffered as well. Indeed, European doctors faced an epidemic: in some urban neighborhoods, 90 percent of children had symptoms of rickets. So could the lion diet cure human beings, too?

Over the next three decades, doctors zeroed in on one substance—not the horsemeat or ground-up bones, but the throwaway ingredient, the cod-liver oil. Something in that oil cured rickets. It was a breakthrough.

The only problem was, that breakthrough contradicted other research showing that the cure for rickets wasn’t cod-liver oil—it was sunshine. It turns out that lions can get vitamin D only through their diet, but if you let kids just run around outdoors, their rickets disappeared.

So which was it? Cod oil or sunshine? Those two things couldn’t possibly be linked … or could they?

Resolving that mystery would require a worldwide effort, and would result in one of the more surprising findings in medical history—the discovery of nothing less than human photosynthesis.

To my ears, rickets sounds incredibly old-fashioned—like gout or ague. So it’s hard to grasp just how common rickets once was—and how devastating.

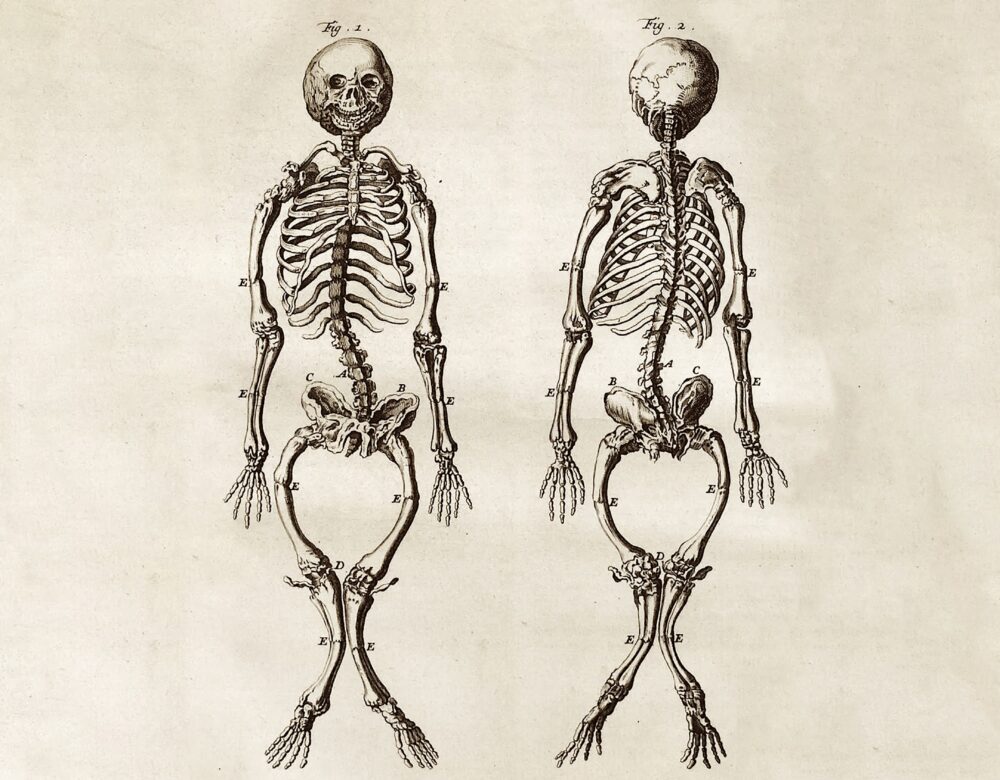

The most common symptom was soft bones. Children’s legs grew rubbery, leaving them bowlegged. Many had breathing problems because rickets distorted the ribcage.

Rickets also warped the pelvis. This was especially dangerous later in life for women, because it narrowed the birth canal and made labor risky. Rickets is one big reason why childbirth killed countless women in centuries past. Their rickets-twisted hips simply weren’t the right shape to deliver babies safely.

I’ve actually put together a bonus episode about rickets and childbirth at Patreon. It explains why C-sections are so common nowadays. It also includes the story of two brother-doctors whose secret medical instrument saved many women in labor from death—even while scaring them half to death. Check it out at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

The first-known rickets cases date back to ancient Egypt, but the disease’s incidence ramped up quickly in Europe in the 1600s. At first, it affected mostly rich people. King Charles I of England had it, as did several Medici children in Italy.

During the Industrial Revolution, rickets shifted from the rich to the poor. Hundreds of thousands of people migrated from farms to cities to work in factories. This included many children, who toiled away for pennies per hour. And something about those circumstances caused an explosion of cases. Again, 90 percent of children in some cities showed symptoms.

England was hit especially hard. Two Charles Dickens characters show clear symptoms: Tiny Tim and the Artful Dodger. But cases abounded all across Europe and North America.

As for the cause, doctors were baffled. They blamed everything from poor ventilation to adulterants in bread to congenital syphilis and over frequent gambling. These were just wild stabs in the dark. They had no idea.

The first clue about the cause of rickets came from a British doctor named Theobald Palm. In the early 1870s, Palm traveled to Japan to do missionary work. He didn’t have much luck preaching the gospel—the Japanese people had their own perfectly fine religions, thank you. But Palm was a gifted and selfless doctor, and treated some 40,000 patients over his dozen years in Japan.

Palm returned to Great Britain in 1880—and something immediately struck him. He’d of course seen rickets cases before, while living in Britain. But he suddenly realized that he hadn’t seen a single case of rickets in Japan. Why would that be?

Curious, he sent surveys to other medical missionaries—in North Africa, Mongolia, India, China, everywhere. And every last one told him the same thing: that rickets was unheard-of there. Only in large, Western cities did children get this disease.

Palm puzzled over his results. He tried to correlate rickets to every factor he could think of—rainfall, altitude, overcrowding, malnutrition, but none of them could explain rickets. Many other countries had worse malnutrition and worse sanitation than European cities. In fact, every other known disease had far higher rates outside Europe—except rickets. Why?

By 1890, Palm had finally puzzled out the answer. A lack of sunlight. In most countries, people spent hours every day outdoors. But Europe, and especially Britain, was cloudy and suffered from pollution that blocked sunlight. It was also cold, which kept people indoors. Most importantly, industrialization had shifted thousands of people from farmwork to factory work. Children in particular either spent their days working inside or in sunless tenements.

Overall, Palm made a compelling case that rickets resulted from a lack of sunlight.

But what about those lion cubs at the Zoo? The ones who sprang back to life after a few drops of cod-liver oil. Similar research showed the same effect on dogs and rats with rickets. Cod-liver oil had long been a folk remedy for rickets as well. All of this made rickets seem related to diet.

So which was it? Diet or sunshine?

Scientists finally got some traction on the answer in 1923. That year, two scientists in London began some experiments on rats.

Eleanor Hume and Hannah Smith kept their lab rats in glass jars with sawdust in the bottom for bedding. They fed the rats a diet known to produce rickets—and sure enough, the rats were soon bowlegged and weak.

At this point, the experiment started. For half the rats, they removed the animals from the jar, and placed the jar—without its lid—beneath a mercury-quartz lamp. This lamp could reproduce the full spectrum of the sun, including ultraviolet light. The air in the jar was irradiated for ten minutes. Then the lid was replaced, and the rats put back inside.

For the other half of the rats, the air in the jar was also irradiated with the lamp. But in this case, the rats themselves were also, separately, irradiated in a wire cage.

Smith and Hume then measured how well the rats recovered from rickets. They found that both sets of rats recovered quite well. They concluded from this that the air in the jar somehow retained the irradiation. And this retained irradiation cured rickets.

So, they ran another experiment to test this conclusion. This experiment also involved rats in jars with sawdust. The air was irradiated, but the rats were not. And this time, before replacing the rats, they had an assistant blow the irradiated air out of the jars. He just took a big gulping breath and <WHEW> blew all the air out.

To Smith and Hume’s satisfaction, this time the non-irradiated rats did not heal. They had solved the mystery of rickets! Irradiated air was the key.

Except, it wasn’t. Another group repeated the experiment and failed to replicate the results. Plus, when Smith and Hume thought more about their theory, the whole idea fell apart.

Most air is outside, so it gets irradiated in the sun. And air isn’t stationary. It’s fluid, and eventually that irradiated air will flow indoors. But if so, why wasn’t that air curing people with rickets? Something wasn’t adding up.

So Smith and Hume repeated their experiment—and this time, they kept a close eye on the assistant. That’s when everything started to make sense.

When Smith and Hume asked their assistant to repeat the experiment and blow out the air in the rats’ jars, they noticed something immediately: that the assistant was fussy. He knew that if he blew into the jar while it still contained sawdust, it would get all over the place—on the floor, on the table, in his hair. Heaven forbid.

So the assistant had been pouring the old sawdust out before blowing, then replacing it with fresh sawdust. And those were the rats, with the fresh sawdust, who were not healing from rickets.

So why did that detail matter? Smith and Hume realized the problem when they examined the sawdust of other rats. It had bits of leftover food in it, plus rat poop.

Now, this is kind of gross, but rats sometimes eat their own poop. They were also eating the leftover food, and even the sawdust. This got Smith and Hume thinking.

Again, some rats had the air in their jars irradiated with the lamp, but were never irradiated directly themselves, and they healed from rickets anyway. But maybe it wasn’t the irradiated air that cured them. Maybe it was the irradiated bits in the bedding—the food and poop.

Another team at Columbia University took this idea and ran with it. They gave rats rickets and then fed them various things, like spinach, flour, and powdered milk. None of these foods cured rickets alone. But when they irradiated those foods under a lamp—presto, the rickets disappeared.

Crucially, the Columbia team also tried this trick with human skin. Now, this is even more gross and creepy: they peeled off skin from a cadaver, irradiated it, and fed that to the rats. But it cured rickets immediately.

At this point, dozens of other researchers jumped into the fray and things got convoluted. But the truth about rickets soon emerged.

The first step involved linking rickets with diet. Scientists in the early 1900s had discovered a new class of nutrients in food called vitamins. Missing vitamins caused various ailments. For instance, a lack of vitamin C caused scurvy. In the 1920s, scientists knew of three vitamins, which they called A, B, and C. So someone proposed that perhaps rickets was caused by a missing vitamin—a theoretical vitamin D.

This hunch proved correct. Vitamin D helps the body process calcium and phosphorus, two elements that make bone strong. Without vitamin D, our bones are starved of calcium, and they get soft and bendy—classic signs of rickets.

Cod-liver oil just happens to be rich in vitamin D. That’s why it cured rickets in the lion cubs and other animals. It supplied a missing nutrient.

So what about sunshine? Well, it turns out that biological cells can also make vitamin D. Whenever ultraviolet light strikes a cell, the cell produces vitamin D automatically. It happens in spinach, flour, even poop. Any organic matter, really.

Including human skin. Even a trace of direct sunlight starts cells churning, pumping out vitamin D. It’s human photosynthesis.

The role of vitamin D in the evolution of human skin is a fascinating topic. It actually helps explain why humans have different skin color. I’ve put together a second bonus episode about this at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

The usual story here involves how light skin evolved as an adaptation to northern climates—a way to get more vitamin D. But that’s not the whole story. In fact, the original innovation involved the evolution of dark skin. Dark skin was the first breakthrough to make humans human. The bonus episode also covers a controversial theory about slavery and rickets that recent historical research has upended. All that at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

By 1930, scientists had a complete picture of rickets. Rickets is caused by a lack of vitamin D. It exploded during the Industrial Revolution because factory work kept people indoors all day and left them crowded in dark tenements with no windows. The poet William Blake once criticized the “dark satanic mills” of industrialization. But the real evil there was less the Satan and more the dark.

And now that medical scientists understood rickets, they set about curing it. In animals, this was easy. The London Zoo installed special glass that lacked iron. Most glass has iron impurities that filter out ultraviolet light. But by installing so-called Vitaglass that lacked iron, the zookeepers ensured that reptiles and monkeys and other animals would not get rickets again.

For humans, doctors recommended that children swallow spoonfuls of cod-liver oil. But this idea was not popular. Mostly because cod-liver oil has the nastiest taste you can imagine—off-the-charts fishiness. Manufacturers tried to mask the taste by blending it with various flavors like mint, cherry, and chocolate. But if anything, that mix sounded even more revolting. Chocolate fish? Yuck.

Children nevertheless kept choking down cod-liver oil throughout the 1930s. The United States actually imported 67 million pounds of it every year, mostly from Norway. But in 1940, Nazi Germany invaded Norway and cut off the supply. The Nazis were waging a rickets war against America.

At this point, the U.S. began adding artificially derived vitamin D to beverages. One was beer. Schlitz Beer got especially enthusiastic. As their slogan read, “Beer is good for you, but Schlitz, with Sunshine Vitamin D, is extra good for you.”

But beer isn’t the best choice for children. So, dairy manufacturers started adding vitamin D to milk, which contains no vitamin D naturally. This was actually clever marketing on their part. Before this, milk was considered a dodgy liquid. It was prone to spoiling and was festering with germs. But with added vitamin D, milk was suddenly good for you.

Adding vitamin D to milk all but eradicated rickets in the United States and Europe. But, with declining milk consumption, rickets is on the rise again in both places.

Of course, there is an easier solution here—just go outside for a bit! And get children outdoors especially. Depending on your skin tone, even twenty minutes of sunshine will give you a month’s supply of vitamin D. I mentioned before that, to me, the name rickets conjures up a bygone era of disease—the days of ague and gout. And a tiny bit of sunshine will ensure that this awful Victorian ailment stays firmly buried in the past.