Animal trials have always been part of society, but we are not talking about the ones with lab mice. In medieval times dozens of animals were tried in human courts for committing human crimes. It sounds silly, but the practice raises an uncomfortable question that we are still grappling with today: if we hold animals accountable in court, doesn’t that mean that they deserve some sort of legal protection? We kill them for food and skin them for leather after all. What about medical and product trials that sacrifice thousands of animals despite the fact that they have had diminishing returns throughout the years?

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

The child-killer was finally facing justice for his heinous crime. It was the year 1386, in Normandy in northwest France. While his two young parents had been making love in the nearby hay, the killer had crept up to the child’s crib and attacked him—maiming his face so badly that he’d died a few days later.

After being chased down, the killer had been jailed, tried, and convicted. Then, per the conventions of the time, the killer was dressed in a new waistcoat and white shirt and marched to the gallows.

Townsfolk hooted and hurled insults on the way, and perhaps pelted the killer with rotten food. But however hungry, the killer was not allowed to stop and eat.

At the gallows, local farmers had brought the killer’s brethren to watch—mostly to deter them from pursuing a life of crime themselves.

Finally the crowd hushed. We don’t know whether the killer spoke any final words. But if so, they probably were something along the lines of this: <OINK>

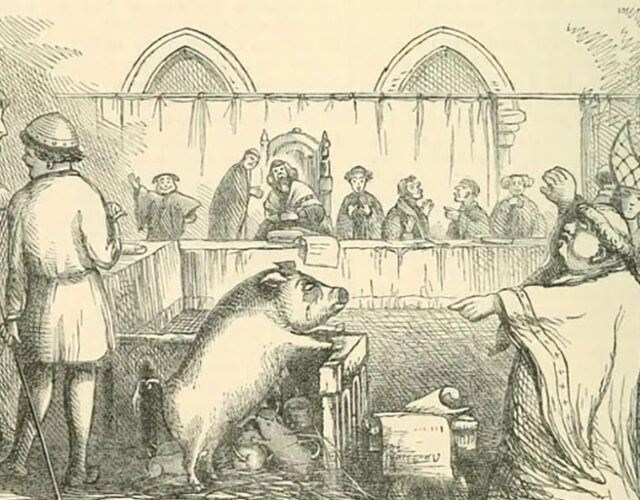

The killer, you see, was a pig. It had attacked the baby in the crib, then been jailed for the offense. Officials later convicted the pig in court and, despite its being a female sow, dressed her in a man’s clothing and paraded her to the gallows.

After the pig had squealed its last squeal, she was trussed up and hanged. The farmers on hand then pointed out her suffering to the pigs they’d brought along to witness, to teach them that a life of crime never pays. And apparently the other pigs learned their lesson. There’s no record of any more attacks on infants in the town.

Now, however strange it seems, this case in Normandy was far from alone. Historians know of dozens upon dozens of towns in medieval times that tried animals in human courts for human crimes. Animal convictions were not rare, not at all.

The obvious question is why. What on Earth were these people thinking dragging barnyard animals into the courtroom?

But while it’s easy to laugh, in truth, there were good reasons for the practice. It’s not quite as bizarre as it seems. And if you think this practice is a relic of medieval times and could never happen today in our enlightened age—well, think again. We’re not as far removed from medieval times as we might think…

The historical record is somewhat hazy, but animal trials were a worldwide phenomenon, with cases in Malaysia and Congo, in Brazil and New Zealand and colonial America.

But for whatever reason, animal trials peaked in Europe between about 1400 and 1700. People in southern and western France seemed especially vindictive, but animals also endured trials from England and Portugal to Russia and the Slavic states.

The sheer number of different animals brought to trial beggars belief. Locusts, moles, storks, termites, serpents, snails, grasshoppers, caterpillars, weevils, turtledoves, even dolphins. It’s a veritable Noah’s ark.

But the most common animal by far was pigs. Pigs were often allowed to run wild in medieval villages. And their immense size, several hundred pounds, meant that they could do real damage—up to and including killing and eating the victim. This was considered an especially shocking thing for pigs to do on Fridays, since Christians in medieval times were not allowed to eat meat on Fridays.

Technically, different kinds of animals were shunted into different court systems. Domesticated animals like cows and pigs were under the control of human beings. Therefore, they were tried in secular courts. A guilty verdict there usually ended with a death sentence.

Wild vermin were treated differently. Locusts and rats and weevils were not under human control—only God’s control. So ecclesiastical church courts handled their cases. These courts punished malefactors with banishment or excommunication.

The charges levelled against vermin usually involved destroying food crops. Meanwhile, domesticated animals usually got charged with murder or property crimes.

Sometimes the animals’ owners faced charges as well. One example of a dual human-animal trial took place in colonial Connecticut. In 1662, a man named William Potter was accused of, quote, “the unnatural deed of carnal lewdness” with animals. In short, he buggered three cows, three sheep, and two pigs. He then had to watch all his lovers be killed before his eyes, one by one. Officials finally hanged him as well.

In other cases, people had more compassion for the animals. In 1750 a French peasant named Jacques sodomized a donkey, and both were hauled into court. But due to a wave of popular protest, the judge allowed several character witnesses to testify—on the donkey’s behalf. The witnesses swore the donkey had always been chaste and pure. The judge was so moved that he acquitted the ass. Meanwhile, the real ass here, Jacques the peasant, burned at the stake.

However bizarre it seems to have character witnesses for a donkey, it does reveal something important: that people took animal trials seriously. Animals enjoyed all the same rights and privileges accorded to human beings. None were arrested before an official investigation, and they received a full trial before a judge while being defended by lawyers.

Domesticated animals, which could be rounded up and captured, actually appeared in court. With wild vermin that could not be rounded up, a church official would march into the field where they lived and read a proclamation requesting their appearance on such-and-such a date.

If a court banished the animals, the sentence was not immediate. Judges often gave animals time to get their affairs in order. One kindly judge even gave a pregnant mole a few extra days to vacate, given her condition.

I think my favorite animal trial involved a man who can only be described as the Johnnie Cochran of kangaroo courts—Bartholomew Chassenée.

In 1510, again in eastern France, a plague of rats began devouring one town’s barley crop. The local bishop brought up charges, and assigned Chassenée to defend the rats. In doing so, the bishop miscalculated badly. He had no idea how clever Chassenée was.

Right away, Chassenée objected to the indictment. The bishop had charged every rat in the region—which was surely unfair. Could His Excellency prove that all local rats had been eating the crops? Not just a few rogue ones?

The bishop no doubt grumbled, but he ordered his priests to read a proclamation where the rats were known to gather. It demanded that the guilty parties turn themselves in and appear in court on a certain date.

Strangely enough, no rats showed up that day. Which of course looked bad for Chassenée’s clients. A sure admission of guilt, right?

Nonsense, said Chassenée. To explain his clients’ absence, he invoked another provision of the law. At the time, if a defendant felt that the journey to court would endanger their life, they had the right to skip the trial. And everyone knew, Chassenée said, that the town was overrun with cats. His clients simply could not appear in court under those circumstances. Their lives would be in danger.

This sophistry must have had the bishop gnashing his teeth. He now had to figure out how to detain all the cats in town for the duration of the trial. Several months soon slipped away. Eventually Chassenée threw up so many roadblocks that the case withered and died. The rats had won. The case made Chassenée famous, and he later served on the equivalent of the French Supreme Court.

Now again, it’s easy to mock these cases. It’s much harder to try to understand why they happened. But there were several reasons, some good and some bad, for why medieval Europeans would try and execute wayward animals.

For one thing, punishing criminal offenders, even animals, made local officials look tough. Animal trials also reassured people that the authorities took crimes seriously and would hold everyone responsible, no matter their age, creed, gender, or zoological status. Justice was so important that not even pigs or cows would escape punishment.

In addition, animal trials fulfilled a need for revenge. If there’s an atrocity in a community, people usually demand that someone—anyone—be held responsible. This might sound dark, but it doesn’t have to be.

Consider the practice of scapegoating. In ancient times, priests would lay hands on a goat and spiritually transfer all of a community’s sins onto the beast. The priest would then banish the goat into the desert, to carry away everyone’s sins.

We might question the metaphysics here, but in a functional sense, scapegoating did two things. It acknowledged the hurt and pain that the sins had caused. And it provided a ceremony to help people move on. Rituals do help us heal.

Medieval people were doing something similar with the animal trials. When an infant got mutilated or a crop got wiped out, life seemed absurd and tragic. The subsequent trial and execution was a way to restore balance in the universe—another ritual to help people heal and move on. There was some deep psychology at work here.

Still, times do change, and animal trials began to decrease in frequency with the rise of the Enlightenment in the 1700s. Enlightenment thinkers emphasized science and reason. And they challenged the idea of convicting someone of a crime when they lacked the intellect to even understand what the law was. It’s no coincidence that insanity defenses also first arose during this time.

But animal trials have never quite disappeared. In 1906 a dog in Switzerland was tried and executed for its role in a robbery-homicide. In a more light-hearted vein, a chimpanzee got convicted in Indiana in the 1920s for violating a no-smoking ordnance when it lit up a cigarette during a circus act.

Unbelievably, a bear in Macedonia got convicted of theft as late as 2008. Its crime was stealing honey from a local beekeeper. Before that, the beekeeper had been deterring the bear by blasting so-called “turbo-folk ” music. Apparently bears hate turbo-folk. Here’s an example…

I’d stay away, too. Unfortunately the generator blasting the music eventually ran out of power—at which point the bear went full Winnie the Pooh and devoured all the honey in sight.

So the man charged the bear in court. The court tried the bear in absentia, and ordered the government to pay the man $3,500 in damages, on the grounds that the bear was an endangered species and therefore a ward of the state. It was sweet, sweet justice, although the bear does remain at large.

Now, animal trials certainly aren’t the only crazy court proceedings in history. In ancient Greece, courts used to try stones and construction beams that had fallen on people and killed them. They were essentially convicting them for obeying the law…of gravity.

People also dreamed up wild trials for witches, like having them eat poison beans or tossing them in lakes. Then there’s an absolutely flabbergasting tale from the Vatican. In the year 897, one pope exhumed a dead pope, dressed the putrid carcass in a robe, and convicted the dead man of high crimes. I’ve actually collected a few of these wild stories in a bonus episode at Patreon.com/disappearingspoon. You should check it out.

But I’d like to end with one final, and perhaps uncomfortable, reason that scholars think animal trials declined. Namely, that convicting animals of crimes brings up all sorts of sticky legal issues about their rights in general.

After all, if we tried animals in courts, just like humans, why wouldn’t animals deserve legal protections in other areas? What right did we have to slaughter them for food or skin them for leather? It was perhaps easier to banish them from court than ask such questions.

But these basic questions about the rights of animals haven’t gone away. They’ve simply taken new form. Consider the monkey selfie case.

In 2008 a British photographer named David Slater traveled to Indonesia and befriended a group of macaques. Then he set up a camera in such a way that the monkeys, simply while fooling around with it, would take a selfie.

It was a cute idea, and the resulting picture was hilarious. A big, grinning monkey. And naturally, Slater wanted to cash in.

Unfortunately, media companies began running the photograph without paying Slater. They did so on the grounds that he hadn’t taken the photograph. The monkey had. And as non-persons, monkeys cannot hold copyrights. The picture, they said, was therefore in the public domain.

Slater sued these publications in court. But in the middle of all this, animal-rights activist jumped in and countersued on behalf of the monkey. Why couldn’t it own the copyright? The activists also wanted to collect damages, which they planned to use to preserve the monkey’s habitat.

Eventually the courts declared the picture part of the public domain. But some legal scholars think that’s shaky. The whole dispute opened up a giant can of worms.

More seriously, animal activists have also sued the U.S. federal government to declare chimpanzees legal persons. Their goal was to stop medical experiments on chimps.

Now at first, requesting that legal designation may sound strange. How can chimps be “legal people”?

But then again, corporations are technically legal persons nowadays. As a result, corporations enjoy free speech and other legal rights. So if Facebook and Walmart are so-called people, why not our closest living relatives? At least they’re biological.

In fact, the U.S. federal government has recently stopped supporting medical research on apes, and several scientific agencies are phasing out research on other animals as well. Europe has even stricter regulations. It’s not the same as dressing a pig in a waistcoat and letting it sit in the docket. But don’t be surprised to see more animals represented in court in the future.

And even with animals that committed heinous deeds, was the old way really so bad? I mean, sure, it was a waste of time to read a summons to rodents. And there is a risk of making a mockery of the court.

But people way back when did take animal rights seriously in some ways. Consider the case of a hangman in Germany in 1576. After yet another pig attacked yet another child, the hangmen went vigilante. He hanged the sow on his own, before a trial could be convened. But the town was outraged at the lack of due process. Rather than hail him as a hero, the town ended up banishing him.

Contrast that with today. Any animal who killed someone now would probably be summarily shot, Old Yeller–style. No investigation, no inquiry. No due process at all.

Now, we probably shouldn’t revive literal kangaroo courts. But perhaps it was better than nothing. And the whole saga leads me to wonder. Did these trials raise animals up to our level? Or did we sink down to theirs?