It was one the largest epidemics in American history: 30,000 men became paralyzed over the course of a few months in 1930. A dogged epidemiologist eventually traced the cause to adulterated bottles of a medicine called “jake,” which was being sold illegally (during Prohibition) as booze. Despite the massive number of victims, historians all but forgot about the epidemic. About the only place it survived was in blues songs in the South, and historians have been using old blues lyrics to piece together certain aspects of the ailment otherwise lost to time.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

For Ephraim Goldfain, the morning quickly got out of hand.

It was February 1930. Goldfain was a 34-year-old doctor in Oklahoma City. First thing that morning, he saw a patient with a mysterious bout of paralysis. The man stumbled in off the street, barely able to walk.

During a consultation, the man said he’d strained his legs lifting a car. A few days later, he felt tingling in his calves. Then the paralysis began. If he lifted his legs, his feet drooped, the toes hanging slack. To walk, he had to take exaggerated steps, lifting his knees extra high, then slapping his limp foot down.

Goldfain suspected that the part about lifting the car was spurious—it had nothing to do with the paralysis. But beyond that, he had no idea where to start. Polio can cause paralysis, but other symptoms of polio were absent in the man. Lead poisoning also seemed a strong possibility. But the bloodwork came back negative.

Goldfain was still puzzling over the case when another half-paralyzed man staggered in. The same symptoms—a spooky coincidence.

Then, incredibly, three more cases arrived over the next few hours—five cases of paralysis overall.

Goldfain was overwhelmed. He talked to one of them in detail: a podiatrist.

The podiatrist said he’d caught the paralysis from his patients. Goldfain asked him how he knew this. The podiatrist replied, “Because they all have the same symptoms.”

Goldfain swallowed hard. There were more?

The podiatrist pulled a list out of his pocket. It had 65 names—all victims. Goldfain was flabbergasted. What on earth was happening?

He grabbed the list, then grabbed his coat. He had to get to the bottom of this outbreak.

He had no idea that he’d just stumbled into one of the largest epidemics in American history. It would come on in a flash, affect tens of thousands of people—and vanish almost without a trace.

In fact, if not for a few musicians who played the blues, the entire saga of Jake Leg might have disappeared from history forever.

After getting the list from the podiatrist, Goldfain headed right out. He ended up interviewing thirty different men in Oklahoma City. They mostly lived in the same neighborhood, one notorious for bootleggers and rough living.

Again, the podiatrist said he’d caught the ailment from his patients, but during his interviews, Goldfain realized the disease couldn’t be contagious. No children caught it, and very few women did, either. That ruled out simple microbes.

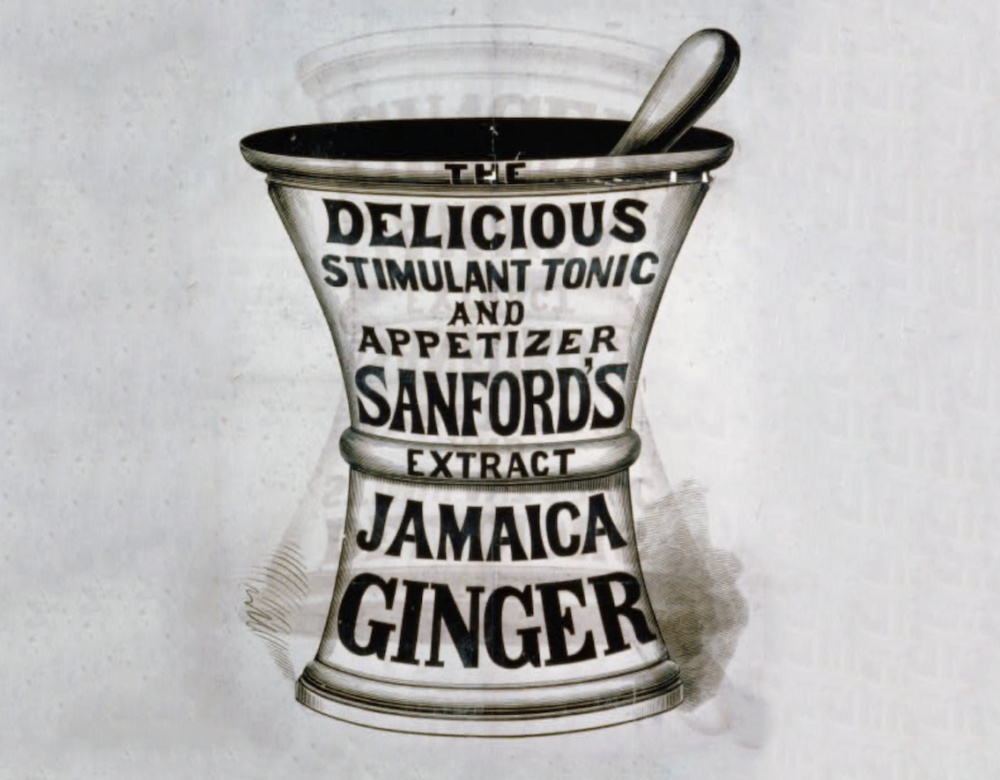

But there was one clue. He asked the men about any medicines they’d taken, and they all mentioned the same one. An elixir called Jamaican Ginger. Or more commonly, just jake.

Jake was sold in pharmacies and grocery stores, although you could also pick up bottles at roadside sandwich stands. It supposedly relieved stomachaches, headaches, and intestinal distress. But everyone knew why people really drank jake. For the liquor.

In 1920, Prohibition had made alcohol illegal in the United States. But this was among the least obeyed laws in American history. Rich and middle-class people bought smuggled liquor from Canada. Rural people employed whiskey stills.

Poor city-dwellers had fewer options. Some of them did truly nauseating things to get their fix. They drank hair tonic or perfume. They’d strain shoe polish through cloth, or stove fuel through bread.

Drinking medicines that contained alcohol was a better option. And of those medicines, Jamaican Ginger was popular. It was an amber liquid that contained up to 90 percent alcohol. A two-ounce bottle cost around a quarter which at that potency equaled four shots of liquor.

And if you’re thinking to yourself, Yum, ginger, I bet that’s tasty … not quite. Under Prohibition, any medicine with alcohol had to contain four percent solid material to discourage illicit consumption. So bottles of jake always had sludge in them.

And it was nasty sludge, mostly ginger-root extract that was cringingly bitter. You could choke it down, but just barely.

To reduce the bitterness, some manufacturers illegally swapped in chemicals that tasted better, like castor oil. Castor oil has another benefit, too. Prohibition agents would sometimes boil a bottle of jake and then weigh whatever remained behind to see if the mixture had the required four percent solids. Castor oil is thick and heavy and has a high boiling point. So it remained behind when the alcohol boiled off. That way, manufacturers could cheat, and didn’t have to add the super-bitter ginger-root extract.

Unfortunately, if a bottle of jake sat on the shelf for too long, the dark castor oil would rise to the top. Government Prohibition agents could see this, and they’d seize the bottles. So most shady manufacturers stopped using castor oil.

So people just had to deal with the taste. Pharmacists would give people a Coca-Cola with their bottle of jake, then open a back room. It was like a low-grade speakeasy, with men sitting around getting hammered—grimacing with every sip.

During his interviews, Ephraim Goldfain realized that every single person who was paralyzed had drunk jake roughly two weeks before the symptoms started. And they’d all bought the jake from the same few pharmacies in that rough neighborhood of Oklahoma City.

However, the problem extended far beyond Oklahoma. Within days of Goldfain’s interviews, several other cities had outbreaks: 400 cases in Cincinnati; 500 in Wichita; and a thousand in Mississippi. Thirty thousand cases appeared in all.

No one had ever seen an epidemic arise so fast. Some people called the plague gingerfoot or jakeitis. Mostly common, they called it jake leg.

The most common symptom was paralyzed feet and a staggering walk. Some people could get by on crutches, but others could not walk at all. Many victims lost the use of their hands, too.

Predictably, all sorts of quack treatments sprung up: zapping victims with electricity, or bathing them in vinegar or petroleum sludge. One cruel doctor gave people excruciating spinal taps and then injected horse serum. But nothing helped.

Cases appeared in ten states, mostly in the Midwest and South. Before long, the federal government’s Public Health Service, the precursor to the Centers for Disease Control, got involved. The main investigator was a doctor and pharmacologist named Maurice Smith.

In his investigation, Smith had two goals. Figure out what caused jake leg, and figure out who was responsible.

Now, people had been drinking jake long before 1930. And most people who drank jake that year nationwide didn’t end up paralyzed. Given how quickly the outbreak happened, Smith reasoned that a batch of jake had been contaminated with something. But what?

Theories included arsenic, carbolic acid, or wood alcohol. Smith needed to find a tainted bottle and test it for different compounds.

Unfortunately, finding the bottles proved diabolically hard. Most victims had already drunk the evidence. And as word of the outbreak spread, pharmacies began dumping their supplies in panic, often tossing bottles down the holes of outhouses.

So, Smith had to visit the outhouses and fish them out. In his published reports, he doesn’t go into detail his retrieval methods, but you can imagine. Although, actually, don’t—it’s probably better not to.

Anyway, Smith tracked down 13 hard-won bottles of jake and tested the contents. They came up negative for everything. No arsenic. No carbolic acid. No wood alcohol. Smith began to fret. What if they couldn’t find any chemicals?

But after some advanced chemical analysis, his team finally found traces of an obscure compound called tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate. It’s a byproduct of making tar. Back then, it was used to make lacquers and to keep fake leather from turning brittle.

Only two companies in the U.S. manufactured tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate, which means it probably hadn’t appeared in bottles of jake accidentally. So why was it there? The reason involved some inspired chemistry.

Again, elixirs like jake had to contain four percent solids. Legally, that meant adding the bitter ginger-root extracts. Bootleggers had tried swapping in castor oil, except it rose to the top of bottles and gave the game away.

But after some testing, Maurice Smith’s team realized that tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate prevented that from happening. A spoonful kept the castor oil on the bottom. It was a clever chemistry hack, and made the jake taste far better.

Smith’s team now had a probable cause for the outbreak of paralysis. There was just one problem. When they consulted medical sources, the books listed tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate as perfectly safe—totally nontoxic.

But that didn’t sit right with Smith. He decided to run his own tests. The standard animals for toxicology work back then were dogs and monkeys, so he fed some tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate to them. And … nothing happened. The dogs and monkeys showed no symptoms. His whole investigation slammed into a dead end.

Luckily, Smith didn’t give up. He fed tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate to some rabbits as well. And to his immense relief, they ended up paralyzed. He later tried it on calves, too, and the same thing happened. They all got jake leg.

It turns out that dogs and monkeys don’t absorb tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate. It just sluices right through them. But rabbits and calves do absorb it, with tragic effects. As do human beings.

Tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate paralyzes people by killing the brain cells that control movement. And while some people recovered, many didn’t. Several victims drank only a single bottle of tainted jake. And from that one night of cutting loose, they ended up paralyzed for life.

At this point, Smith had gotten half of what he needed. He’d figured out the cause of jake leg. Now, he just had to find who’d done this.

One odd thing that scientists noticed about jake leg was the seeming lack of victims who were Black. Which didn’t make sense. After all, Black people drank jake at roughly the same rate as White people.

A few doctors at the University of Oklahoma suggested that perhaps Black people were biologically immune for some reason. And they tested this theory with perhaps the stupidest experiment I’ve ever heard of.

They obviously couldn’t just give tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate to Black people and White people and risk harming them. So instead, they got hold of some black and white…chickens. They apparently reasoned that feathers and skin color were close enough.

So they fed the chemical to white chickens and black chickens and charted their symptoms. Sure enough, white chickens suffered more. Therefore, they concluded, black skin must protect humans more.

Other doctors had a different explanation—a far more plausible one. They reasoned that Jake leg probably did hit Black communities. But Black people didn’t visit doctors as often, either because it cost too much, or because most doctors were White.

That theory turned out to be correct. Black people simply suffered jake leg in silence, and remained invisible in medical reports.

Still, despite the lack of medical documentation, another type of documentation did exist in the Black community. Listen…

<MUSIC>

That’s a song called “Jake Walk Blues.” Here’s another snippet, from the song “Jake Leg Blues.”

<MUSIC>

Most blues musicians in the 1930s were Black, and several songs from the era make reference to jake leg. And in some ways, the songs did a better job of documenting the epidemic than doctors did.

You see, limb paralysis was the most common symptom of jake leg. But squeamish doctors often avoided talking about the immobility of another body part—impotence.

In short, many victims of jake leg could no longer get erections. Doctors didn’t want to talk about this, but blues musicians were willing to. One lyric ran, “You have numbness in the front of your body. You can’t carry any lovin’ on.”

Even more than the paralysis, this side effect ruined some men’s lives. One victim was interviewed four decades after the onset of his symptoms. The interviewer asked if he’d ever been married. The man couldn’t even answer. He just dropped his head and started weeping.

Knowledge of this symptom might have disappeared forever if not for the blues. And we certainly wouldn’t know how hard it hit the Black community without it.

So, who was responsible for this tragedy? It wasn’t easy finding out. Given its illegal nature, bootlegging was beset with sketchy, fly-by-night characters. At one point, several states thought they’d found the villain—a man named S.A. Hall.

Multiple grand juries indicted him. They finally tracked this criminal mastermind down, only to find that the address for S.A. Hall was actually a Salvation Army Hall. The bootlegger had been having his mail delivered there. He himself was long gone.

However, the dogged Maurice Smith finally traced the tainted bottles of jake back to a single company in Boston. It was run by two brothers-in-law, Harry Gross and Max Reisman.

The two of them hit upon using tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate in their jake after talking to a chemist they knew. And to be fair, they insisted that the chemist write a letter to the company that manufactured the chemical to make sure it was safe. The manufacturers got back and promised it was.

But it turns out, the manufacturer hadn’t bothered testing the chemical. According to the law then, they didn’t have to. In fact, you could put anything you wanted into medicines then, as long as you labeled it accurately. Cocaine, heroin, industrial solvents, it didn’t matter. You just had to label it.

So, Gross and Reisman bought 135 gallons of tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate for $40—enough to make half a million bottles of tainted jake. Then they shipped it all over the country, with tragic consequences.

Unfortunately, prosecuting Gross and Reisman proved difficult. When it came to medicines then, the entirety of the law was basically, Buyer, beware. Prosecutors could charge them only with mislabeling their product and adulterating a supposed medicine to make it drinkable. Those were mere misdemeanors, despite the 30,000 cases of paralysis.

Plus, the brothers-in-law lied their way out of further trouble. They swore up and down that they were just middlemen. They claimed that two dastardly bootleggers in New York had actually tainted the jake, and they’d just shipped it. The judge swallowed this story whole and gave them just two years of probation and a thousand dollar fine. That’s around 3 cents per victim.

The judge also made them promise they had to track down the New York bad guys. Gross and Reisman solemnly promised to, but did no such thing, because the New York villains didn’t exist.

Maurice Smith was furious about this light sentence, but there was nothing he could do. Later, Harry Gross violated his probation and ended in prison, but Max Reisman never did see the inside of a cell.

Sadly, this was not the only outbreak of tri-ortho-cresyl-phosphate poisoning in history. I’ve put together a bonus story about another case at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It happened in Morocco in 1959. In this case, Moroccan people were duped into consuming jet-engine oil from a U.S. military base. It was a huge international scandal, and it turned into a proxy Cold War battle for hearts and minds in the region. Check it out at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

The jake leg epidemic remains one of the worst mass poisonings in U.S. history. Yet it remains all but unknown today, largely due to shame.

In general, the public blamed the victims for drinking jake in the first place. And the victims themselves felt ashamed of their disabilities. It isn’t rational, but that’s what happened. Otherwise, no one wrote memoirs or gave interviews to reporters. Indeed, the only place the pain was captured was in blues songs. Like these lines, from the song, “I Got the Jake Lake, Too”:

“Boys, Jamaica ginger

Sure will do its part.

Boys, Jamaica ginger,

Will kill your honest heart […]

Now you’ve heard my story,

But I haven’t told half,

This on your tomb

Will be your epitaph.

I had the jake leg,

I had the jake leg, too.”