During WWII, nine Soviet scientists starved to death surrounded by millions of delicious fruits, seeds, and nuts. Were they mad? No. They wanted to save humankind from doomsday.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

It sounded like the beginning of an Agatha Christie mystery. A man is found dead, alone, slumped over his desk. There’s no obvious foul play, but there is one curious detail. In his fingers, he’s clutching a packet of peanuts.

The scene’s even more mysterious given the state of the man’s body. He was an agricultural scientist, working in Russia during the brutal siege of Leningrad during World War II. And one look at his emaciated frame would tell you, poignantly, that he died of starvation.

But wait. If he was dying of starvation, why didn’t he eat the peanuts in his hand? What gives?

The mystery only deepens when we find out that the peanut scientist wasn’t the only victim. That same month, at the same institute in Leningrad, a colleague of his starved to death while watching over her precious potatoes. Yet another colleague starved with thousands of grains of rice at hand. In all, nine scientists at this institute died of hunger during the Leningrad siege—all surrounded by thousands of pounds of rice, barley, peas, fruit, and more.

Buy why? Were they mad? Were the seeds and grains poisonous or rotten? No. They had their wits about them, and the plants were quite nutritious. Yet they all starved rather than eat them.

Let’s call this mystery The Case of the Starving Scientists. And the only way to solve it is to understand their world: Where they were coming from. What they were studying. And why their work—on biodiversity—was important enough to die for.

***

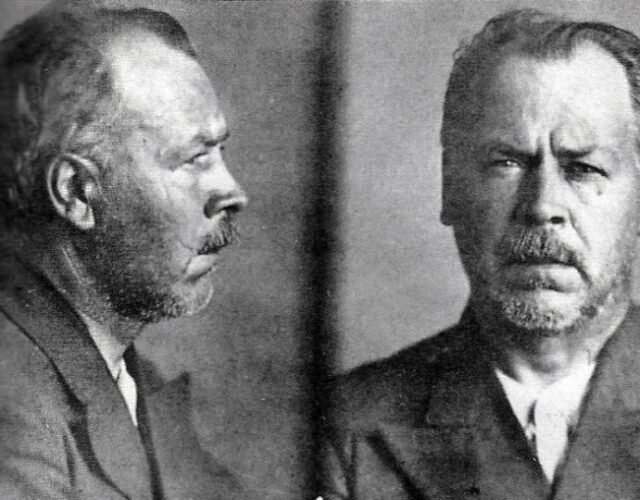

That research institute with the starving scientists is now called the Vavilov All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Plant Industry—or V-I-R in Russian. VIR was named after Nikolai Vavilov, one of the most remarkable and original scientists of the twentieth century. As his biographer said, “If justice be done, [Vavilov] would be as famous as Darwin.”

One crusade drove Vavilov’s life: stopping famines. He was born in 1887, and every few years during his childhood, something bad would lay waste to crops—droughts, insects, disease, brutal cold. One famine alone killed 400,000 people.

Relief kitchens were sometimes set up to feed people during these famines. But the food was awful. Vladimir Lenin dismissed the bread as, quote, “a lump of hard black earth covered with a coating of mold.” Novelist Leo Tolstoy was blunter, calling the food, quote, “vomit, regurgitated by the rich.” Even emergency measures, then, couldn’t prevent people from dying.

Vavilov tried a different approach. He tried stopping famines through the exciting new field of genetics. In short, he argued that preventing famines meant making crops more resistant to cold or drought or insects or disease. Unfortunately, he knew that modern crops are frighteningly inbred. There’s virtually no genetic variety in modern crops—no biodiversity. They’re monocrops. And the narrower a population’s genetics, the more susceptible to threats.

But monocrops do have distantly related wild versions, as well as obscure, off-brand cultivars. And randomly, some of those wild species or cultivars will have better tolerance for cold or drought or bugs. They’re more famine-resistant.

The only problem was, those resistant varieties might not taste good. But genetics could help here. Vavilov knew how to cross resistant varieties with tasty varieties and produce a hybrid plant that was both hearty and good to eat. With genetics he could create crops with the best of both worlds.

But again, the whole scheme required biodiversity. You needed multiple varieties of wheat or barley or whatever to mix and match. And sadly, even back then, many rare varieties were disappearing due to human development. Vavilov saw the best tool we have for fighting famines—biodiversity—slipping through his fingers.

That’s why Vavilov founded VIR. The institute sat in a grand, three-story building off the majestic St. Isaac’s Square in Leningrad, which is modern St. Petersburg. The building had dozens of windows and a cream-colored façade with white arches and pillars. It looked more like a museum or decadent hotel.

But that appearance shouldn’t fool you. VIR was the Ft. Knox of agriculture—a repository to store and protect rare crops and keep them from dying out. And not just from Russia. Vavilov knew that famines killed people all across the globe. So, he started traveling the globe to gather rare crops and bring them back to VIR.

Vavilov made these trips wearing an Indiana-Jones-style fedora and sporting a thick black mustache. He eventually made 115 expeditions to 64 countries, collecting 380,000 seeds, grains, and fruits.

The variety was astounding. As one historian said: “[S]ome [were] dull-coated, while others glistened like jewels … [some were] knobby and gnarled [some] smooth and burnished as a clay pot … [they exuded] every fragrance imaginable—musky, fermented, citric, and floral.” The world had never seen a collection like it.

Every so often, Vavilov would send the seeds out to fields or orchards or paddies around the vast Soviet empire, and have technicians grow them. Then they’d harvest the resulting plants for fresh seeds or fruits and send those back to the institute for storage. The logistics were formidable. But by 1939, Vavilov had a humming empire of his own—25,000 workers, all directed from the stately VIR building in Leningrad.

And within a few years, that whole empire collapsed.

Vavilov’s downfall can be traced to a debate within Soviet science over nature versus nurture—whether inborn genetic traits or outward environmental factors shape our lives more profoundly. Nowadays scientists know that debating nature versus nurture is too simplistic. Both genes and environment shape us.

But that fact wasn’t clear back then. And many Soviet officials believed that environment alone mattered. Above all, the Soviets wanted to sweep away old human institutions and build a new type of human—a selfless, heroic worker. And they wanted to make these changes quickly. By remaking the environment, they hoped to remake humankind within a generation.

Genetics, however, threatened this vision. Genetics emphasized fixed, inborn traits. This implied that perhaps humans could not be refashioned so easily.

As a result, Soviet officials despised genetics. Some went so far as to deny the existence of genes. Eventually they outlawed genetics entirely.

And Vavilov, a prominent geneticist, soon became scientific public enemy number one. One day in 1940, while he was collecting seeds in Ukraine, agents from the future KGB tapped him on his shoulder and arrested him. Not even his wife and children knew where he ended up, but everyone feared the worst—the Gulag. This arrest also left his colleagues at the VIR trembling. They feared they would be next.

Meanwhile, other threats were looming, too. In June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Two of the biggest armies in history clashed, and Leningrad—the heart of Russian art and culture—was a major target.

In fact, Hitler was so excited to goose-step into Leningrad that he printed up invitations to his planned victory speech there, awaiting only a date. He envisioned giving his oration from the balcony of the Hotel Astoria on St. Isaac’s Square.

But while Hitler dreamed of hotel balconies, his scientific minions fantasized about raiding the building across the street from the Astoria—the VIR. These scientists knew Vavilov had gathered priceless troves of crops there, and they were eager to get their grubby hands on them and start experimenting. They might have been working for the Soviet Union’s bitterest enemy, but they alone appreciated the Soviet scientist’s work.

After the Nazi invasion began, officials in Leningrad began evacuating the city’s cultural treasures in July 1941. Especially from the legendary Hermitage Museum—several million paintings, sculptures, gems, coins, and more.

This rescue effort can only be described as epic. Hordes of students and artists and laborers in Leningrad worked around the clock. And in two days—just two days—this small army packed 1.5 million pieces of art into boxes. That’s 520 pieces every minute, almost eight per second. The art then left the city in trains up to 53 boxcars long. As a result, these treasures spent the war 1,500 miles distant, safe from Nazi hands.

In comparison, what support do you suppose the VIR scientists got? Not a single volunteer to help move, not a single train car. Think about that discrepancy. I mean, art is important, absolutely. But we can survive without gems and sculptures. The VIR was housing the collective global heritage of food—irreplaceable cultivars and varieties. But when asked whether they wanted to save them, Soviets officials said, nyet. Those filthy geneticists could fend for themselves.

Imagine what this must have done for morale at the VIR. Their boss had already been disappeared. They were demonized and called traitors for their science. Now Nazis were marching on Leningrad, eager to steal their life’s work. Who wouldn’t despair?

Then things got even worse. The battle for Leningrad deteriorated into a deadly slog. And rather than waste lives and resources in a shooting war, the Nazis laid siege to the city. Their main weapon now would be the very thing Vavilov had worked his whole life to prevent—famine. They intended to starve the Russians out.

***

Those first few months of the siege in Leningrad, people pulled together. They ate stores of grain and tinned goods and tightened their belts to get by. Then, supplies dwindled. Rationing went into effect, then strict rationing. Adults were reduced to just a quarter-pound of bread per day.

After a certain point, though, you can’t tighten your belt anymore. You start getting desperate. Residents started hunting dogs and cats. Soon they were reduced to eating lipstick, leather hats, and fur coats. Eventually even those ran out.

So again, imagine the morale at the VIR. You’re disgraced, you’re scared—and now you’re starving. No one believes in your mission. And you’re surrounded by the only viable food in the whole city. What do you do?

If you’re the VIR scientists, you just keep working. As one survivor later said, “It was hard to walk. It was unbearably hard to get up in the morning, [even] to move your hands and feet … but it was not in the least difficult to refrain from eating up the collection.” But none of them ever succumbed. They worked with food, thought about food, touched food every day. But they never put a morsel to their lips.

Still, the scientists could see their starving, wild-eyed, sunken-cheeked comrades walking by every day. All it would take was one rumor to start a raid. One person remembering, Wait a second, don’t they store food in there? One whisper, and the building would be overrun.

So eventually the VIR scientists barricaded themselves into the freezing basement. Their only company was a plague of rats. Rats always know where the food is. The scientists had to beat the rats off with metal rods while they listened to Nazi artillery explode overhead. And they still didn’t eat a single crumb.

So why didn’t they succumb? Why didn’t they say to hell with the rats and the Nazis and just eat and save themselves? Because they weren’t thinking about themselves. They were thinking about bigger things.

First, they were thinking about the world after the war. Nations would need help getting back on their feet, especially in places where crops had been destroyed. They could help with that.

They were also looking at human history. Ever since the first farmers planted the first seeds 10,000 years ago, there’s been an unbroken chain of plantings through time. Think about that—no nation, no state, no religion has ever survived that long. And the VIR scientists saw themselves as stewards of this heritage.

Eating the seeds or nuts or fruits would have snapped that chain. It would have cut us off from that heritage—and threatened our ability to grow crops in the future.

So the VIR scientists waited—and waited—and gradually died. The rice scientist and the potato scientist and the scientist clutching a packet of peanuts in his hand. In all, 700,000 people starved in Leningrad during the siege. But I defy you to find any deaths more poignant than those nine scientists.

After 872 days, the siege finally lifted in spring 1944, when the battered Nazi army withdrew. Imagine the jubilation in the city. Food, real food, flooded in, and people could eat their fill, beyond their fill, for the first time in years.

But it was a bittersweet moment for VIR scientists. They were happy to be rid of the gnawing hunger and constant temptation, certainly. But they were crushed that their late colleagues couldn’t celebrate with them. They were also disheartened to finally learn the fate of their guiding light, Nikolai Vavilov.

After his abduction in Ukraine, the Soviets threw Vavilov into the Gulag and interrogated him mercilessly, for twelve hours at a stretch. They were determined to make him confess to his so-called crime of not conforming his science to the ideals of communism.

But as one historian put, “Vavilov, unlike Galileo … refused to repudiate his beliefs.” Speaking for his colleagues, he looked his interrogators in the eye and said, “We shall go into the pyre—we shall burn. But we shall not retreat from our convictions.” The Soviets simply could not break Vavilov.

At least not mentally. Starting in spring 1942, the Soviets essentially did to Vavilov what the Nazis tried to due to Leningrad—starve him into submission. They fed him nothing but mashed cabbage and moldy flour day after day after day. The man who’d sampled wild apples in Kazakhstan, wild barley in Ethiopia, wild potatoes in Chile, was reduced to eating flavorless mush, and little of it. His muscles wasted away, turning his arms and legs to sticks. His cheeks caved inward, and boils erupted on his skin. He’d labored for decades to end famine, and he finally succumbed to starvation himself in January 1943. He was 55 years old.

Thankfully, Vavilov’s work outlasted him. The VIR is still working to preserve our global food heritage. And he inspired the even bigger Ft. Knoxes of agriculture that exist today. In fact, I’ve put together a bonus episode at patreon.com/disappearingspoon about one of them—the so-called Doomsday Seed vault in Norway. It’s a truly incredible place—the world’s best hope for preserving our food heritage in the uncertain future. You can also hear about other seed vaults that, unlike VIR, were destroyed by wars and other disasters. That’s patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Today, Vavilov’s work is more important than ever. Despite advances in technology, crops today are more inbred than ever—even more genetically narrow and even more vulnerable to pests and diseases. Climate change could make things even worse as our weather grows more extreme. You might have heard that crops like bananas and chocolate and coffee are already threatened by extinction. Now imagine a world without wheat or corn or rice.

We need biodiversity more than ever. Humankind has been farming for 10,000 years now. And if we manage to survive another 10,000, we just might have Vavilov and the starving scientists of Leningrad to thank for keeping us going.