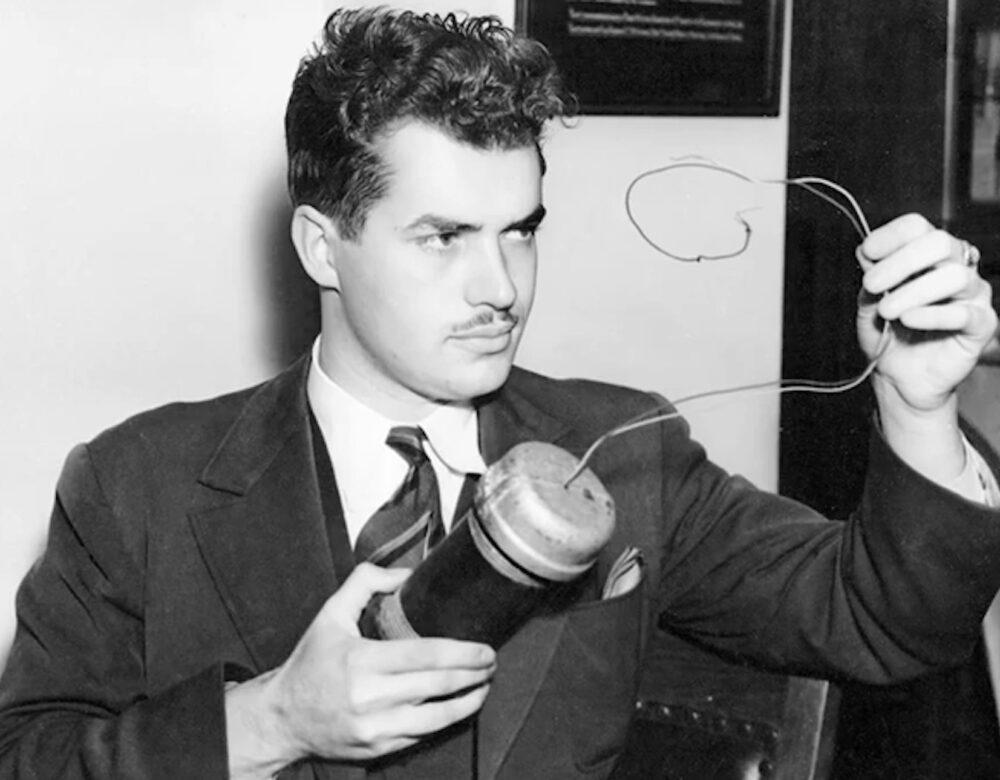

Jack Parsons was a brilliant rocket scientist, but he lived a wild lifestyle. With a devil-may-care attitude, he was pretty relaxed about safety and dabbled in drugs, occult practices, and sex-cult rituals. It would all eventually catch up to him though.

Listen to Part 1 of this two-part series.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineering: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

This is part 2 of a two-part series. So if you missed part 1, I suggest you listen now.

When World War II ended, rocket scientist-slash-devil worshiper Jack Parsons was living with his occult friends in a commune in a grand mansion on Millionaire’s Row in Pasadena, California. And in August 1945, a fresh face showed up there—a former navy lieutenant named L. Ron Hubbard, the future founder of Scientology.

Parsons was immediately smitten. Parsons practiced a magick-based religion. It involved communing with gods and demons. And Hubbard was the most gifted, most natural magician Parsons ever met. Hubbard had an amazing gift for contacting otherworldly apparitions.

Parsons quickly welcomed Hubbard into his commune’s inner circle. And Hubbard repaid this generosity—by sleeping with Parsons’s young girlfriend, Betty. In fact, Betty soon ditched Parsons to date Hubbard full-time.

So did Parsons kick him out of the commune? Sock him in the teeth? No. Parsons was angry, but magick was a far higher priority, and he didn’t want to alienate Hubbard and his gifts.

In fact, Parsons soon approached Hubbard with an offer. Parsons wanted to revive his childhood fantasy, and summon a spirit from another realm. Specifically, a goddess named Babalon. A.k.a., the Scarlet Woman.

To be blunt, the Babalon/Scarlet Woman was a sex goddess. Parsons had a theory that the world then was ruled by a violent demigod. His evidence was World War II. By summoning a sex goddess from another dimension, Parsons hoped to teach the world to love.

And to Parsons’s shock and delight, the spell actually worked.

One reason Parsons was so delighted to meet L. Ron Hubbard was that, frankly, his professional life as a rocket scientist was in shambles. Even though, over the previous few years, he’d been responsible for some major breakthroughs.

Parsons secretly wanted to send astronauts to the stars, but most scientists then considered such ambitions loony. So Parsons focused on military applications, like building rocket motors to help airplanes take off faster.

Parsons first tried using gunpowder. But the ingredients in gunpowder separate over time, which can cause explosions instead of a steady burn.

So in the early 1940s, Parsons harkened back to his childhood. As a boy, he’d taken the gunpowder inside cherry bombs and mixed in glue to keep the powder from separating. Given his inexperience then, his rockets still mostly exploded and left craters in the yard. But the idea of using glue as a binder still seemed promising. So the adult Parsons began experimenting.

He finally developed a promising recipe: a mix of gunpowder, glue, corn starch, and fertilizer. His team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory decided to test this mix in so-called JATOs—jet-assisted takeoff motors.

His team bolted several JATOs under the wing of a small, lightweight aluminum plane. Like all planes then, this one had a propeller to help fly. The JPL crew snapped the propeller off. This plane would fly—or not—on jet-rocket power alone.

When everything was ready, an army pilot fired up the JATO motors. Nothing happened; the motors choked. Parsons’s team grumbled and tinkered, then told the pilot to try again.

This attempt—did not go well. One motor exploded, tearing rivets out of the wing. Shrapnel also blasted the plane’s body, tearing a hole in it. The pilot was lucky to survive.

But a week later, the pilot bravely climbed back into the cockpit for a third test. You can imagine Parsons pacing and holding his breath. What would go wrong this time?

Nothing. The motors fired right up, and the pilot blasted down the runway. He took off at a distance 30 percent shorter than normal. Parsons and JPL had just launched the first-ever American vehicle with jet-rocket motors. Quite an achievement for a self-taught, ragtag chemist.

Still, the whole experience had been dicey. The gunpowder-glue mix was still prone to exploding. By June 1942, Parsons knew he needed to shift away from gunpowder. But to what?

At this time, he had also been contemplating liquid-fuel motors. Liquid propellants are mixed right before ignition and therefore cannot separate. Unfortunately, using liquids requires pumps, which complicated the motor.

But one hot afternoon that summer, Parsons happened to see some roofers working. They were pouring asphalt—a thick, oozing liquid that solidifies into a solid. Suddenly, everything clicked.

Asphalt burns readily. It’s also liquid, so you can mix in other propellants. But it hardens into a solid, so nothing separates. And because it’s a solid, you don’t need pumps, either. Asphalt combined the best of both setups. It’s both fuel and glue—a brilliant combination.

Parsons started experimenting immediately. He found that a mix of asphalt with potassium perchlorate burned perfectly. He finally had the rocket fuel of his dreams. Perhaps the stars weren’t so far off.

Unfortunately, Parsons’s main funder, the army, was less enamored. One problem with asphalt rockets is that you can’t turn the motor off. Once you ignite the asphalt, it just burns, burns, burns until it runs out. That’s not ideal for planes.

So, the army demanded that Parsons focus on purely liquid-fuel rockets. However annoyed, he obeyed. And within a few months, he achieved a second major breakthrough.

Again, liquid-fuel motors combine two propellants and ignite them with a spark. But it proved hard to build a reliable ignition system.

So Parsons began experimenting with chemicals that ignite spontaneously upon mixing. It’s like two people who can’t stand to be near each other: as soon as they interact, boom. Some liquids do the same when mixed. After trying various combinations, Parsons successfully built a spontaneously burning liquid-fuel motor using aniline and nitric acid.

In the span of one year, then, Parsons invented two completely new types of motors—the basis for the first practical rocket engines. Both were low-cost and high-performance—what we’d call disruptors today.

During World War II, the U.S. military used Parsons’s engines in thousands of planes. The boost in speed they provided allowed planes to take off on aircraft carriers, a major advance. Planes could also now land in remote areas with short runways and rescue troops. This saved an estimated 4500 lives during the war.

Given the high demand, Parsons’s JPL colleagues founded a company to manufacture motors. One suggested calling the company Superpower, but others said no. That sounded too juvenile, too much like Superman.

Instead, they called the company Aerojet. It would go on to become one of the most celebrated aviation companies in history. Despite possessing zero business skills, or really any business sense, Jack Parsons became a vice-president.

But before long, Parsons’s interest in the occult became a major liability for Aerojet.

Parsons’s lifestyle among the occultists in the commune was mostly harmless. He’d spend hours in the bathtub playing with toy boats. He’d greet people at the door holding a giant snake. He’d conduct séances to contact Egyptian gods. Typical shock-the-bourgeoisie stuff.

Other activities proved more troubling. Earlier, Parsons had abandoned his wife to date her then-17-year-old sister Betty. Other commune members were accused of sleeping with a 16-year-old boy. Neighbors spied naked, pregnant women jumping through bonfires in the yard.

Parsons was also making illegal bathtub absinthe, as well as taking cocaine, speed, morphine, and peyote. His many, many hungover mornings enraged other Aerojet executives.

Finally, they had enough. They fired Parsons. And in truth, this was probably wise. At that point, Aerojet didn’t need his explosions of insight anymore. They needed the steady, reliable burn of 9-to-5 work. Which was not Parsons’s forte. Aerojet had business contracts, and needed FBI security clearances. Parsons had to go.

Still, in appreciation, Aerojet gave Parsons $11,000 in severance. However devastated about the firing, the money allowed Parsons to purchase the commune’s mansion as a consolation prize. He had now come full circle. His family had lived on Millionaires’ Row as a child, but had been forced to leave due to money problems. Now he had a house of his own there. People began calling it the Parsonage in his honor.

And then, as mentioned before, L. Ron Hubbard showed up at the door in August 1945. Despite their romantic rivalry, Parsons latched onto Hubbard. To Parsons, rocketry and the occult were intimately intertwined. Rocketry freed the body from the surly bonds of Earth, while the occult freed the mind and soul. And with his rocketry career in shambles, the occult was all Parsons had left. So he convinced Hubbard to help him summon the sex goddess Babalon, or the Scarlet Woman.

They began the summoning ritual in January 1946. As for what they actually did during it, I’ve read their notes, and frankly, I can’t make heads or tails of it. They consecrated a dagger, played classical music, sprinkled some blood around. Maybe you had to be there.

But they swore that spooky things happened in response. A lamp fell. The electricity went out. A windstorm began. Totally unexplainable stuff.

Then they waited. And soon, a Scarlet Woman did walk into Parsons’s life. A former navy PR officer visited the Parsonage, curious about the religious worship and magic she’d heard about from friends. Her name was Majorie Cameron—a vivacious woman with stark red hair.

Parsons became obsessed with Cameron. After all, he thought he’d summoned her from a different realm. They began a torrid affair, and basically locked themselves into a room for five weeks of lovin’. Parsons sincerely thought of this sex as a magick sacrament to bring world peace. The two eventually got married.

But not before L. Ron Hubbard screwed Parsons over again.

In 1946, Hubbard approached Parsons with a business plan. Hubbard proposed buying yachts on the East Coast, sailing them to California, and selling them for a steep markup. Parsons, the poor boob, agreed. He blindly gave Hubbard his life savings, nearly $21,000.

Shortly after which, Hubbard disappeared to Miami, taking Betty with him. At first, Parsons was too distracted with his Scarlet Woman to realize he’d been scammed.

When it finally dawned on him, he raced over to Miami. He found a yacht they’d purchased, The Blue Water, but not the couple. But a few nights later, the harbor called to say that Hubbard and Betty had just fled.

Parsons locked himself into his hotel room and got out his book of spells. He decided to summon a weather demon to stir up a storm. The ritual involved pentagrams and geomancy, whatever that is.

And, coincidentally or not, a storm really did kick up off the coast. Hubbard and Betty’s yacht got clobbered; a sail was torn off. They limped back to port to find Parsons waiting for them.

Parsons ended up getting some of his money back, but not all. After that, he and Hubbard parted as enemies.

And while Hubbard went on to wealth and fame through Scientology, Parsons’s life began unraveling.

After being fired from Aerojet, Parsons wanted to get back into rocketry research. But the field had changed on him. It wasn’t ragtag dreamers in the desert anymore. Businesses were popping up. The military was involved. People needed security clearances from the FBI.

At first, Parsons cooperated with the FBI. He even informed on a few colleagues, ratting them out as communists. But when the FBI examined Parsons’s own life, they were horrified. He read communist newspapers. He’d slept with a 17-year-old. He summoned demons! The FBI soon stripped Parsons of his clearance, meaning he couldn’t work in rocketry. He had to take jobs as a washing-machine mechanic and a hospital orderly instead.

Eventually, former colleagues intervened. They said Parsons was too brilliant to waste on washing machines. So the FBI relented and restored Parsons’s clearance.

But a few months after securing a new job, Parsons got caught stealing documents, reportedly to sell to foreign governments. He got fired again, and the FBI stripped him of his security clearance permanently.

Frustrated, unable to work, Parsons soon embraced occultism completely. He declared himself the Antichrist. He also began visiting prostitutes for more sex-magick rituals. The poor women must have been terrified.

Before long, Parsons had to sell the Parsonage—the second time he’d been ejected from a home on Millionaire’s Row. He moved into the coach house with his wife instead.

To make money, he set up a lab in the garage, where he made special-effects chemicals for Hollywood—pyrotechnics, fog, things like that.

One afternoon in June 1952, Parsons got a rush order for some pyrotechnics. He headed down to his lab and started mixing chemicals. Around 5pm, two quick explosions rocked the neighborhood. Bang-bang.

Neighbors rushed over to find a huge hole in the ceiling. The lab’s windows were shattered, and the heavy garage door had been torn from its hinges.

Amid this wreckage lay Parsons. His right forearm had been blown off, and half his face was missing. He died within forty minutes. His last words were, “But I’m not finished yet.”

No one knows what caused the accident. Parsons had always been cavalier about danger, and probably just dropped some explosives he was mixing. That caused the first bang. Dangerously, he often kept other explosives just lying around. Those probably ignited and caused the second bang.

But rumors have always swirled about darker explanations. A neighbor on the scene supposedly found a syringe of morphine in the lab trash can. Was Parsons high? Others whispered that the rush-order story was a coverup. They swore he’d been driven to suicide, or was trying a new magick spell.

Some people even invoked conspiracies. In 1938, a crooked L.A. police captain had been caught planting a bomb in a detective’s car. Parsons’s testimony at the trial had sent the man to prison. Well, that captain had been released from prison just days before Parsons died. Was that a coincidence? Many people doubted it.

Regardless, Parsons died too young, just 37 years old. And he left a complicated legacy.

Occultists still revere him. In some circles, he’s even given credit for attracting the first alien visitors to Earth. After all, he was a rocket scientist. And his first big ritual to summon beings from another dimension took place in 1946. UFO sightings began the very next year at Roswell, New Mexico. Surely not a coincidence!

In reality, there’s a much more interesting explanation for Roswell. I’ve actually put together a bonus episode about it at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It might surprise you to hear that the Roswell affair really did involve unidentified flying objects—just not the type of UFOs you’re probably thinking. That’s patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

In rocketry research, Parsons’s legacy is both more precarious and more secure.

Secure because he was unquestionably one of the greatest rocket scientists in history. Both his solid-fuel and liquid-fuel motors were big breakthroughs. NASA’s Titan rockets as well as the Space Shuttle were both based on his work. When someone once referred to Wernher von Braun as the father of rocketry research, von Braun shook his head no. He insisted that Parsons deserved the name more.

And yet, groups like Aerojet and JPL—groups that Parsons cofounded—are reluctant to embrace him. It’s not hard to see why. Parsons was pretty loony.

But maybe that looniness wasn’t incidental to his genius. It can’t be a coincidence that the most eccentric rocket scientist around also had the most original ideas. As they say, there’s a fine line between insanity and genius.

If Parsons had lived, there’s no way he ever would have worked at NASA. The agency was too buttoned-up, too straitlaced. In many ways, the establishment simply used Parsons—milked him for ideas, then discarded him.

But Parsons sure didn’t do himself any favors. He led a reckless life. And he certainly had no need to summon demons. He already had plenty of his own.