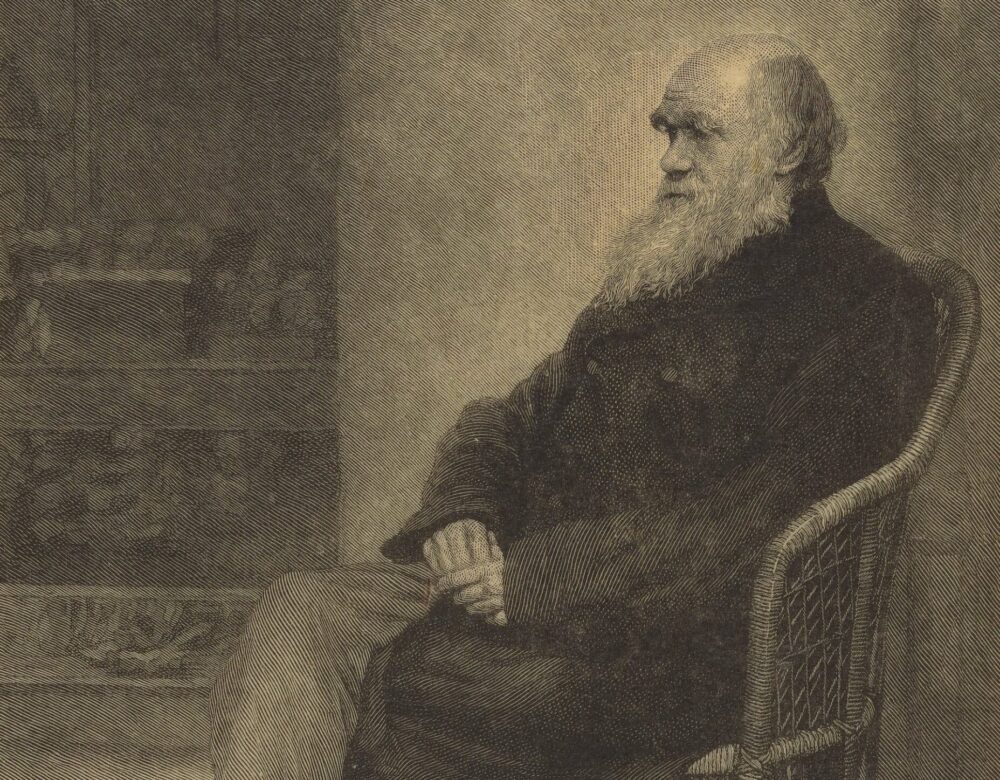

“Survival of the fittest.” It’s a twisted-up shortening of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Despite not coining the phrase, Darwin is still closely tied to it. Even worse, the quote may have inspired a gruesome murder: something else the scientist became entangled with.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

Hey, everyone, a quick message. This is the tenth and final show in the fall season. After this we’ll be taking a break until spring.

If you’re craving more science history delights before then, check out the Science History Institute’s other incredible podcast: Distillations. Or check out the dozens of bonus episodes I’ve posted at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. In the meantime, enjoy this episode, and I’ll see you in the spring.

And oh, before I start, in case you cannot tell from the title, there is a murder in this story, and this episode contains graphic violence.

The landlady opened the closet door, and nearly vomited. She had never smelled anything so foul. What had those dirty students left in this bundle of clothing?

She had rented a room to the students two weeks earlier. They had seemed like decent fellows, and even paid upfront. But after they hauled this bundle of clothing up to the room, they’d vanished—leaving her to clean up this mess.

The landlady sighed. Holding her nose, she picked up the dirty bundle. At which point two severed arms and two severed legs tumbled out.

The landlady had just uncovered one of the most sensational murders of nineteenth-century Paris—the slaying of a poor old milkmaid. The case proved sensational not only for the ghastly crime, but for the motivation behind it.

Because as strange as it sounds, one of the murderers killed the milkmaid simply to prove something about Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Which in turn raised an urgent question in French society. Was Charles Darwin to blame for this murder?

Aimé Barré’s tastes always outran his budget. Barré was a bearded, 25-year-old stockbroker in Paris who loved spoiling his mistress. He gave her jewelry and designer clothing all the time.

But his speculations in the stock market never paid off. He would take money from clients and, instead of investing in sound securities, would gamble on some longshot and lose everything. Then he’d scramble for more clients to make up the shortfall. He began drowning in debt.

That didn’t stop Barré, in 1878, from moving to an expensive new apartment near Notre Dame. He kept himself afloat by bleeding his father, a carpenter, for money. But even family love has its limits; his father cut his ne’er-do-well son off. A desperate Barré resorted to forgery and blackmail, but he was no better at those than he was at picking stocks. Both ventures failed.

He did have one hope. Across the street from his apartment, he noticed an old woman named Gillet who sold milk. She had gnarled hands and a scarred left arm. She was also quite thrifty. Neighborhood gossips swore she had 5000 francs squirreled away, about $15,000 today.

Barré heard this figure and began salivating. He approached Gillet and begged for a chance to run her estate. He promise to double her wealth. But he came on a bit strong; Gillet sensed his desperation and refused. A fuming Barré then turned to his friend, one Paul Lebiez.

Lebiez was the tall, handsome, 24-year-old son of a photographer. He had first met Barré in school, where Lebiez distinguished himself as a brilliant budding scientist. After school, Lebiez took some anatomy courses and applied to join the navy as a doctor.

Before accepting him, the navy put out feelers about Lebiez’s character. Although many people regarded him as a warm and happy-go-lucky person, others called him “difficult and unruly.” He also had a reputation as a political firebrand. Ultimately, the navy rejected him.

Lebiez began teaching in Paris instead, but he was soon fired for chronic tardiness. Like his friend Barré, he also ran up several debts.

But Lebiez differed from Barré in one way. Barré was grubby, materialistic. Lebiez had an intellectual streak. And one of his touchstones was Charles Darwin’s new theory of evolution by natural selection.

Darwin has always been controversial, but he was especially so in France. Part of this was snobbery—the reflexive French disdain for anything English. Catholics and conservatives in France also fretted about how evolution seemed to displace God and undermine traditional morals.

Even French scientists split over Darwin. Some of them held a torch for the alternative ideas of biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who promoted a looser, use-it-or-lose-it theory of evolution. Other scientists saw Darwin’s merit but hesitated to speak up for fear of being labeled an atheist or a radical.

Darwin’s support was especially weak among the establishment types who dominated the august French Academy of Sciences. Six separate times before 1878, progressive scientists had nominated Darwin for election to the Academy—and six separate times, Darwin had been voted down. The message was clear: Darwin had no home in France.

Paul Lebiez, however, adored Darwin, and he was not shy about saying so. Lebiez was a firebrand, and he had no career to ruin anyway by speaking up in Darwin’s favor.

When Lebiez heard that Barré was also in financial trouble, the two old school pals commiserated. They actually discussed committing suicide. It seemed like their only option. Then Barré mentioned the old milkmaid, and how she had rebuffed his attempts to manipulate her finances.

In mentioning her, Barré might simply have been blowing off some steam. But Lebiez pounced on Gillet and began denouncing her as a miser. As Lebiez said, “What right has she to hoard up her gold when … others … could put it to some use?” Lebiez considered it the duty of the weak, like Gillet, to give way to the strong, like him. To him, this was simply Darwinism in action.

Lebiez certainly was not the first person to twist Darwin’s theories like this. A decade earlier, the Englishman Herbert Spencer began promoting so-called Social Darwinism. Social Darwinism conceived of human life in terms of conflict—strong people brushing aside the unfit, powerful nations dominating weak ones. There was no room for pity, no remorse. It was actually Spencer, and not Darwin, who coined the phrase “survival of the fittest.”

The flaws in Spencer’s thinking are many. Most obviously, human beings are not mere barracuda and chum. We have morals, logic, reasoning. We can cooperate for the greater good. We’re certainly no angels, but we can think beyond our immediate needs and rise above a lions-versus-gazelles mindset. In truth, Darwin provides zero guidance on morals. That’s something that we have to figure out ourselves.

Nevertheless, some people did twist Darwin’s theories into ethical principles. Paul Lebiez in Paris was one of them. And Lebiez soon made a chilling suggestion to his friend Barré: to kill the weak milkmaid Gillet and grab her money for themselves. Barré quickly agreed.

Because Barré had met Gillet before, he planned to visit her apartment to dispatch her. Three times he invented some excuse to wheedle his way into her flat. And three times he chickened out. Lebiez must have been wondering whether his friend really was one of the strong ones. A chagrined Barré finally agreed to lure Gillet to his apartment instead, so Lebiez could help.

On March 23rd, 1878, Barré convinced Gillet to visit him and deliver some milk. She arrived around 10am. Barré let her in with a smile—then smashed her skull with a hammer.

After crumpling to the floor, she cried out for mercy. Mercy, however, was for the weak. A lurking Lebiez ran up and stabbed her six times in the heart with a stiletto.

The squeamish Barré left to ransack Gillet’s apartment. Meanwhile, Lebiez used his anatomy training to dismember Gillet’s body. He packed her head and torso into a trunk, and wrapped her arms and legs in some blue blouses that Barré had bought for his mistress.

Barré returned from Gillet’s apartment with bad news. Neighborhood scuttlebutt had greatly exaggerated the milkmaid’s wealth. Rather than 5,000 francs, Gillet had only 2,000 to her name.

Barré then made a proposal—that he, who had bigger debts, keep the lion’s share of the loot. He’d give Lebiez around 75 francs. Talk about a risky idea! Did he really expect that the cold-blooded Lebiez would agree to that?

Incredibly, though, Lebiez did. Barré pocketed most of the cash. Meanwhile, Lebiez walked away from the murder with the modern equivalent of less than $250. Apparently, to him, carrying out his Darwinian duty was reward enough.

The coverup was as clumsy as the murder. Lebiez and Barré deposited the trunk with the torso and head on a train bound for Le Mans. Then they rented a room from a landlady under a false name and dumped the bundle of clothing with the legs and arms in the cupboard.

They chose the room for its proximity to a medical school. They hoped that when the police found the limbs, they would assume that some med students were playing a crass joke—dumping a cadaver there to gin up rumors and scandal.

And at first, the police swallowed the bait. When the limbs were discovered on April 6th, they did assume a prank. But a visit to the medical school revealed that no bodies were unaccounted for. Suspecting something darker now, the police began inquiring about missing people around town. On April 17th, they got a report about Gillet the milkmaid. She had a scar on her left arm that matched the scarred left arm found in the room.

From there, things proceeded swiftly. Neighbors told the police that Barré had been hounding Gillet for money. On Good Friday, the police hauled Barré into the station, where the landlady identified him. Barré quickly confessed, and implicated Lebiez.

Lebiez was in the countryside then, on an excursion to collect tadpoles and frogs to dissect. His debts notwithstanding, he hoped to purchase a microscope with his blood money and continue his anatomical studies. But the police caught up with him on Easter Sunday and cuffed him.

Predictably, the French tabloids ran screaming headlines. It was a real-life Grand Guignol. Respectable French papers exhibited more restraint. And however sordid, the tale probably would have faded from memory if not for one thing.

Word soon got around that, on April 11th, two weeks after the murder, Lebiez had given a public lecture on—Darwinism, and the natural tendency for the strong to dominate the weak. In Lebiez’s words at the talk, “At the banquet of Nature there is not room … for all the guests. Each one struggles … [T]he strong push out the weak. … [F]amily against family, species against species, a civil war without peace or truce.”

It was Social Darwinism incarnate. And it didn’t exactly take Sherlock Holmes to link these sentiments to the recent murder. Lebiez was basically laying out his justification. And many in French society saw those words as a golden opportunity.

Catholics, conservatives, and their allied newspapers began denouncing Lebiez as a heinous criminal. More importantly, they began using him as a cudgel to destroy Darwin and evolution.

Far from perverting Darwinism, those newspapers thundered that Lebiez had simply followed Darwinism to its logical conclusion. One called him a “puppet intoxicated by the doctrine of his master.” Darwinism, they said, was nothing but amoral, might-makes-right nihilism. Society therefore had a duty to root out this evil.

Rhetorically, this seemed like a strong case. A vocal supporter of Darwin really had killed someone weaker than him for explicitly Darwinian reasons. You can imagine people reading along and nodding. But as the campaign to destroy Darwin picked up momentum, something funny happened.

Frankly, most French people then had never heard of Charles Darwin. Why would they have? He was just some foreign savant, most of whose published work was about barnacles, worms, and pigeons. Suddenly, though, Darwin was everywhere, in newspapers of all persuasions. And French folks wanted to know more. What was this Darwin brouhaha?

So, some newspapers began running stories to explain Darwin’s theories, especially the more liberal newspapers. Many took pains to avoid distortions and smears. And oddly enough, when everyday people began reading what Darwin actually said—a lot of them decided it kind of made sense.

Especially when respected scientists began weighing in. Again, many scientists had hesitated to speak up for Darwin before. But the Lebiez murder, and the public controversy surrounding it, forced the scientists to take public stances in meetings and interviews.

Thus arose a virtuous cycle. The more that common people read about scientists supporting Darwin, the more public opinion shifted in his favor. This made it easier for other scientists to pipe up, which shifted public opinion further. Which encouraged more scientists to speak out, and so on.

Slowly, then, the great tide of public opinion lifted Darwin out of the muck. And it did so in spite of the ongoing negative publicity from the trial of Lebiez and Barré.

After months of headlines, the trial opened in late July 1878; it lasted just a few days. Cravenly, each of the friends tried to blame the whole mess on the other. (So much for being strong.) The jury believed neither one of them, and swiftly returned a sentence of death.

Meanwhile, just four days later, the French Academy of Sciences once again took up the question of whether to elect Charles Darwin a member.

His odds did not seem good. Would you support someone accused by the Church of providing justification for murder—especially if he was English? Darwin should have been defeated more soundly than ever.

But that’s not what happened. Despite the murder rap, the seventh time was the charm, and in August 1878, Darwin finally became a member of the prestigious French Academy. The results were not a landslide, and the scientists who voted aye justified themselves by muttering that Darwin had done some excellent work in botany. But the timing spoke volumes: the public interpreted the election as a slap to those who had been disparaging Sir Charles.

I’d like to end with this. If something about the Lebiez-Barré affair has been tickling your mind, pinging memories of some story you’ve heard before—well, you’re right. Their story echoes one of the greatest pieces of literature ever written.

On September 7th, 1878, Lebiez and Barré had their heads chopped off with a guillotine. But their story continued to fascinate the public. So in the early 1880s, a French writer named Alphonse Daudet began writing a book about the Lebiez-Barré murder.

Daudet labored for years on his book—and then abruptly quit in 1884. Why? Because the first French translation had appeared of a novel by the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The book’s name was Crime & Punishment.

Crime & Punishment tells the tale of a struggling young man named Raskolnikov who murders an old lady. He ends up stealing a trifling sum of money from her. But his real motivation was his belief that strong beings like him had a right to exploit the weak. In his deranged morality, superior types can dispose of lesser beings however they like.

The writer Daudet read Crime & Punishment and groaned. He realized he could never compete with Dostoyevsky’s genius. Despite years of investment, he abandoned his book on Lebiez and Barré.

There’s no evidence Dostoyevsky ever heard about the Lebiez-Barré murder. It couldn’t have influenced Crime & Punishment anyway, which came out a dozen years earlier, in 1866. But it’s hard not to marvel over the coincidence. The idea was apparently in the air. And Dostoyevsky himself had wise things to say about Darwin.

Like many religious people, Dostoyevsky felt uncomfortable with how natural selection displaced God. But he was also intellectually honest enough to see the overwhelming evidence for evolution in nature. Dostoyevsky rejected the conservative cant. And given his masterful novel, he certainly would have seen through the sophistry of Lebiez, as well. He knew that nature’s laws are not equal to human laws, and never will be. Again, morality is something we have to figure out for ourselves.