The Haber-Bosch process is famous for allowing industries to develop cheap synthetic fertilizer, and thanks to it, human beings crank out 175 million tons of ammonia fertilizer every year that helps to feed half the world. Its namesakes, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, however, are deeply controversial figures. Their stories tell us a lot about how science and scientific fields got entangled with Nazism.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

Hey, everyone. This is the last episode of the spring season. I’ll be back this fall with more episodes. If you’re craving science history stories in the meantime, check out the wonderful Distillations podcast from the Science History Institute.

Plus, some exciting news: As I mentioned before, I have a new book coming out soon, called Dinner With King Tut. It’s about experimental archaeology—people recreating things from the past. I’ve never written a book that’s been more of an adventure!

The book comes July 8th, but you can preorder it now. In fact, I have an exclusive offer for podcast listeners. If you preorder now through my publisher, you’ll get 20 percent off the hardcover.

Just use the code “Spoon” at this website: bit.ly/dinnerwithkingtut. Again, the website for 20 percent off the hardcover is bit.ly/dinnerwithkingtut. Offer code “Spoon.”

You can also find that link in the show notes, or at samkean.com/podcast. So please, pick up a copy before that offer expires. Preorders are vital for books. And now on with the show.

In the early 1930s, white-collar professionals in Germany were frustrated. The economy was in shambles after a decade of hyperinflation. At one point, the cost of a loaf of bread, which had been 250 marks, shot up to 200 billion marks.

Unemployment was rampant, too, even for doctors and engineers. And those who did find work often suffered big salary cuts. All of which explains why many people in those professions embraced the rise of the Nazis.

Now, a lot of them disagreed with the Nazis on certain issues. Many even found them extreme. But because the Nazis at least promised to do something to help these professionals out, they welcomed them.

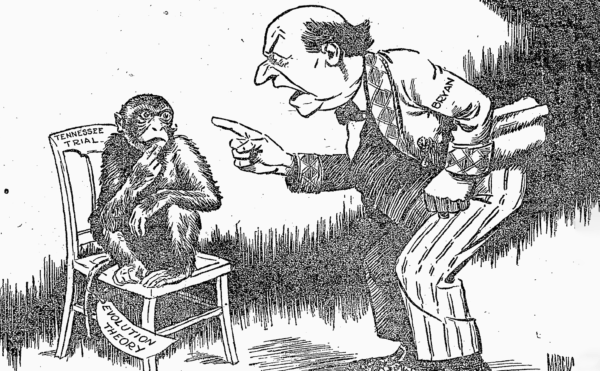

So today, we’re going to examine why—why so many people in technical fields embraced Nazism. Because however uncomfortable it is, scholars have documented that there’s something about the scientific mindset that seems to drive certain people into radical and even violent politics.

Nazism was popular among physicians. Half of all German doctors joined the Nazi party. Half! That’s compared to 10 percent of the overall population. And most doctors joined pretty early, in the party’s initial days.

A decade ago, a group of psychiatrists and lawyers wrote a paper examining why doctors found Nazism so attractive.

Now, to be clear, a few doctors, frankly, were evil. They wanted to experiment on human beings without any restraints. They did awful things like give people unnecessary organ transplants and expose people in concentration camps to excess heat or cold. These doctors ended up killing at least 1100 prisoners, and injured or maimed at least 400,000 more.

But most doctors weren’t just evil. They embraced Nazism for other reasons.

One reason involved rhetoric and propaganda. Medicine then was emerging from centuries of well-meaning but often harmful quackery. Doctors were embracing the scientific methods instead and making great strides.

Nazism made similar claims—that it was the rational application of science to politics. Those claims look ludicrous now, of course. But physicians wanted to be scientific, and because the Nazis supposedly did as well, some doctors believed them. Some doctors also hoped that the Nazis would fund research programs that aimed to rebuild society according to supposed biological laws.

Moreover, many doctors also saw the Nazis as a ticket to gain prestige. Now, most doctors enter medicine for selfless reasons: they want to help people. But some doctors also seek prestige. Doctors are community leaders. They have high status. They make lots of money; they schmooze with powerful people. And aligning themselves with the Nazis was a ticket to more power.

Another reason is a trend medicine still grapples with today. Medicine was quite hierarchical. It had rigid structures of command, especially in hospitals. It was paternalistic, too: doctors thought they always knew what was best for patients. And there were right and wrong ways to treat patients.

Sometimes, that attitude is a good thing in medicine. You don’t want a free-spirited improviser for a brain surgeon. But back then, that rules-heavy, hierarchical mentality often bled over into the political beliefs of doctors. As a result, they proved more susceptible to authoritarian rhetoric—where political overlords know what’s best for common people and prescribe solutions to them.

And to go back to economics, the Nazis provided convenient scapegoats to blame for people’s employment troubles: new graduates, women entering the workforce, and especially Jews.

Disturbingly, many German doctors also embraced ugly rhetoric about Jews. Although they were a small percentage of the German population, Jews formed the majority of doctors in several major cities. In tough economic times, non-Jewish doctors resented this—even those who had Jews for mentors and colleagues.

Finally, the Nazis were health fanatics. They began public-health “wars” on smoking and cancer, which doctors supported. But then the Nazis extended this rhetoric to “racial hygiene.” They talked about cutting Jews out of society just like you’d cut tumors out of a body. And shockingly, many doctors embraced that idea, too.

For all those reasons, doctors flocked to the Nazi party at higher rates than any other profession. And doctors were seven times more likely to join the most fanatical parts of the Nazi movement, like the notorious SS security police. It was a sad state of affairs, and helped enable Hitler’s Holocaust, which murdered 6 million people.

Other fields rode the coattails of the Nazis as well, including archaeologists. They were enlisted to invent a glorious past for Germany. But any alliance with the Nazis provided only short-term benefits. The Nazis infiltrated professional organizations and demanded loyalty oaths. Before long, promotions depended less on competence and more on what the Nazis called “political correctness” and ideological purity.

In contrast, engineers fared better under the Nazis. That’s partly because the Nazis had to keep them happy—keep them churning out planes and radios and bombs. Many engineers were content to just bury their heads and build things—especially when they could cash in. The most glaring example of this involved the so-called Haber-Bosch process.

The German chemist Fritz Haber is one of the most divisive figures in science history. I wrote about him in my book Caesar’s Last Breath. Haber was notorious for his work on chemical warfare during World War I. This work sprang from his fierce patriotism for Germany, and most of the worst gases of the war trace back to him.

At the same time, Haber also did things that benefited humankind immensely. Most importantly, he figured out how to take nitrogen gas out of the air and turn it into a useful product—ammonia.

Ammonia in turn allowed chemists to mass-produce fertilizer for the first time. This proved to be an inflection point in human history—right up there with the first time human beings diverted water into irrigation canals or smelted iron ore into tools. As people said, Haber had transformed the very air into bread.

Still, Haber’s breakthrough was mostly theoretical. He proved you could make fertilizer from nitrogen. But the output from his apparatus was mere dribbles—you could barely have nourished your tomatoes, much less fed a nation. Scaling Haber’s process required different skills—skills possessed by a thirty-five-year-old engineer at the BASF company in Germany. Carl Bosch.

Carl Bosch tackled each of the subproblems with ammonia production independently. One issue was getting pure nitrogen, since regular air contains oxygen and other impurities. For help here, Bosch turned to the Guinness Brewing Company. Fifteen years earlier, Guinness had developed the most powerful refrigeration devices on the planet—so powerful they could liquefy air.

Bosch was interested in the reverse process—taking cold liquid air and boiling it. Curiously, although liquid air contains many different substances, each one boils off at a separate temperature. Liquid nitrogen boils at -320°F. So all Bosch had to do was liquefy some air with the Guinness refrigerators, warm the liquid to -319°F, and collect the nitrogen fumes. Every time you see a sack of fertilizer today, you can thank Guinness stout.

Bosch also found catalysts to speed the process up—aluminum oxide and calcium mixed with iron. Perhaps most importantly, he partnered with the Krupp armament company. Krupp manufactured legendarily large cannons and artillery like the Big Bertha. For Bosch, the company built thick steel vats to withstand the enormous pressures that ammonia production required.

Within a few years of Haber’s first drips of ammonia, BASF had erected one of the largest factories in the world. It was, as one historian marveled, “a machine as big as a town. The plant contained several miles of pipes and wiring.” It used gas liquefiers the size of bungalows. It had its own railroad hub to ship materials in, and a second hub just for transporting its ten thousand workers. Within a few years, ammonia production doubled, and then doubled again. Profits grew even faster.

But even that factory wasn’t big enough for Bosch. He pushed BASF to open a larger and even more extravagant plant over the next several years. This one stretched two miles long and a full mile wide.

This factory launched the modern fertilizer industry, and it has never slowed down since. Even today, the Haber-Bosch process consumes at least one percent of the world’s energy supply. Human beings crank out 175 million tons of ammonia fertilizer every year.

And that fertilizer helps feed half the world. One of every two people alive today, 4 billion of us, would struggle to have enough food to stay alive if not for Haber and Bosch.

And how I wish the story of Haber and Bosch ended there—happily. But pride and ambition tainted this triumph.

Carl Bosch had a rough time after World War I. After Germany surrendered, French officials demanded the right to “inspect” BASF’s ammonia factories. Ammonia can be used to make explosives, and the Frenchmen supposedly wanted to make sure Germany had stopped doing so. In reality, they just wanted to steal Bosch’s technology.

In fact, at the peace talks in Versailles, ammonia technology was a point of contention. Bosch got summoned to Versailles as a BASF representative. Upon arrival, he was locked into a hotel surrounded by barbed wire.

And after a few days of forced “negotiation,” Bosch realized that he would have to give up the ammonia technology one way or another. Still, he wanted the best terms possible. So he took a risk one night one night and scaled the fence to meet secretly with French manufacturers. There he signed a pact to help build a plant in France—provided that the French left BASF alone.

They didn’t. In the 1920s, France forcibly occupied BASF plants in Germany in lieu of reparations payment. So Bosch instructed his workers to shut down machines, rather than let the French see how they worked. The French government got so furious that they sentenced him in absentia to eight years in jail for sabotage.

Bosch regained some international respect in 1931 when he won the Nobel Prize for his achievements in high-pressure chemistry. In doing so, he joined Fritz Haber as a controversial Nobel laureate.

By this point, BASF had merged into a larger company called IG Farben. IGF continued to make ammonia, but Bosch transitioned into other work. He channeled his knowledge of high-pressure chemistry into oil and gasoline production.

Bosch had honed this knowledge in the mid-1920s when the world seemed to be running out of crude oil. All the early gushers were running dry, and companies like IGF were scrambling to develop synthetic alternatives. Bosch was convinced that liquefying coal and refining it into gasoline was the best option.

But the work proved tougher than expected. Liquid coal proved a huge mess. It was tar-y and hard to work with. It gummed up every pipe and valve that Bosch’s team used.

Worse, wildcatters in Oklahoma and Texas made some of the biggest oil strikes in history in the 1920s. And as oil prices plummeted over the next decade, Bosch realized that he would never be able to bring the costs of liquid coal down enough to compete.

Unfortunately, Bosch had staked his career and reputation, and in some ways the company’s financial future, on synthetic gasoline. He faced ruin. So in the 1930s, he began scrambling to secure government contracts to bring in money however he could. Which led him to Adolf Hitler.

Truth be told, the Nazis horrified Bosch. He shielded his company’s Jewish employees from harm, and he helped many Jews find jobs overseas.

At the same time, Bosch agreed to meet with Hitler privately. And he listened with rapt attention as Hitler waxed on and on about his love of automobiles, and he was thrilled at Bosch’s suggestion that they could secure a good Aryan source of synthetic gasoline. Hitler also wanted to fuel his rapidly expanding military.

At the meeting, Bosch did ask Hitler if he could maybe spare some Jewish scientists. But this appeal to Hitler’s decency went about as well as you’d expect. Hitler thundered, “If Jews are so important to physics and chemistry, then we’ll just have to live without physics and chemistry for a hundred years.”

Bosch immediately backed down, all apologetic. And to make amends, he praised the Nazi regime in print, and he attended rallies with swastikas and sieg-heil salutes.

The IGF fuel contracts proved critical for the Nazi military in World War II. By 1944, factories designed by Bosch were supplying a quarter of the gasoline in Germany. They used a workforce that was at least a quarter prisoners and slave laborers. Hitler considered them so critical to the Reich that he ringed them with the best anti-aircraft defense system in Europe; even Berlin was less heavily guarded. In a real sense, Bosch made the Nazi blitzkrieg possible, both by developing the technology to liquefy coal and especially by making sure the Nazis got the first drink at the trough.

Engineers in other industries did much the same, supplying the Nazis with guns, engines, and rubber. In comparison, many prominent scientists in Germany, like Albert Einstein and Max Planck, refused to bow to Hitler.

Even Fritz Haber, who had longed to see Germany rise to power again, reviled National Socialists, the former name for the Nazi Party, as scum—partly because he was Jewish himself. Haber’s fame and status shielded him somewhat, but he also went out of his way to insult Hitler.

In 1933, after Hitler dismissed all Jews from the German civil service, Haber penned a biting letter of resignation. He wrote, “For more than forty years I have selected my collaborators on the basis of their intelligence and their character, and not on the basis of their grandmothers.”

His resignation made headlines across Germany and embarrassed Hitler. Unlike Einstein or others, no one could dismiss Haber as a weak pacifist.

Afterward, Haber arranged to emigrate to Switzerland and start over. But by this point, the Nazis were seizing funds from Jews to fuel the war. This included Haber’s fortune from the ammonia work. It was a final knife in the back. He was now destitute. And when he began looking for jobs in other countries, he received zero offers. Despite his Nobel prize, despite his standing up to Hitler, no one could get past the stench of gas warfare on him. He finally landed an unpaid post at Cambridge University.

Haber was now facing ruin, as well as a multitude of health problems. So he appealed to one last colleague, Carl Bosch.

Although the two men weren’t friends, Bosch had often expressed his gratitude to Haber. He’d also once pledged to help Haber if he ever needed it. So Haber wrote to him: “I took your words seriously. … Won’t you make it possible for me to live out these remaining years … in peace and decency?” Bosch never replied. With no other options, Haber left England and died of a heart attack in Switzerland in January 1934.

Bosch did speak out a little against the Nazis later. Unfortunately, he also slipped into depression and started hitting the bottle pretty hard, and perhaps abusing painkillers.

Bosch soon retired from public view. Meanwhile, IGF continued to ramp up synthetic gasoline production for Hitler. Bosch died in 1940 with Germany still ascendant, but he had no illusions about how badly things would turn out. As he said near the end, “It’s a terrible gift when one can foresee the future. … My entire life’s work will be destroyed.”

Of course, that wasn’t the real tragedy here. The real tragedy was the tens of millions of lives that his work, and his choices, helped destroy during the war.

The problems here aren’t just limited to World War II. I’ve put together a bonus episode about engineers and modern-day terrorism at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. This includes the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington. The crew responsible for that was overrun with engineers—although the reason why will probably surprise you. All that and more at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

I admit, this is a hard topic to discuss. I’m sure most listeners of this podcast think about science as a force for good in the world. The same holds true for adjacent disciplines like medicine and engineering. And I do think those fields do vastly more good than harm.

But that doesn’t mean the harm is zero. As history shows, doctors can be vile Nazis, scientific breakthroughs can be used for evil, and there is no such thing as a world where science and society are separate.