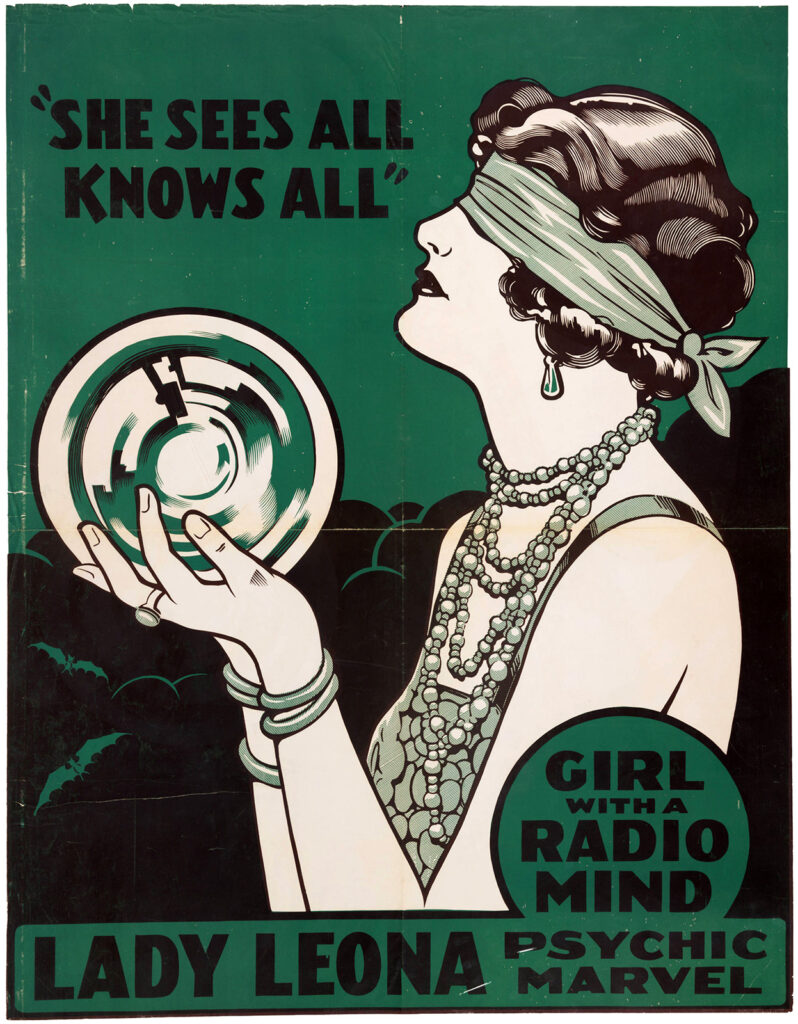

THE STORE WAS DIMLY LIT, with walls painted a deep purple and the sweet smell of incense in the air. Beck emerged from the back of the shop, introduced themselves, and walked with me to the consultation room for my “Celtic cross reading.”

They sat down in a large wicker chair and shuffled the cards while we chatted about the new shop and the surprisingly robust support from the community following the run-in with the police chief that had put Beck Ravenswood (at the time, Beck Lawrence) on my radar. After a few minutes they asked if there was anything I was particularly interested in talking about. Aren’t we all interested in the same small set of topics: job, relationships, health?

At some point, they laid out the cards on the small table between us. For the next 45 minutes or so they used the cards as signposts in an encouraging and generally optimistic reflection on work and happiness.

Notably absent were any predictions, any specific references to the future. Beck didn’t tell me I would become wealthy or find my soulmate. They didn’t promise a better job waiting for me around some corner. Instead, they talked about how to approach life, how to think about the challenges that inevitably arise, and how, in a general sense, to draw on past experiences when confronting new difficulties. It felt like a cross between an encouraging conversation with a supportive friend and a personalized theater performance.

I left having enjoyed the experience but having learned nothing concrete about what the future held, not even where to find a good meal. Standing in front of the shop, I looked across the central square and spotted Hanover’s own Famous Hot Weiner. At least now I knew where I would have lunch.

A couple weeks later I went to my dermatologist for my annual skin check. I pulled into the parking lot of an unremarkable medical building in the Philadelphia suburbs. The waiting room, also generic, was bright, the walls were a nondescript beige, and the air smelled faintly antiseptic. I checked in at the counter, sat in a chair, and, when called, went back to an examination room. After a few minutes the physician walked in, introduced himself, and began the exam.

He started with my head, looking carefully around my scalp. On the side of my head he found a slightly raised spot, a mole. He asked if I had noticed it. I had. He inspected it for a minute and then expressed concern. He wanted to remove it and have it tested. The implication seemed clear: removing the mole reduced the chance it would develop into melanoma. Fifteen minutes and a small patch of skin later, I left. After a few days somebody from the office left a message on my phone: the mole was benign.

I juxtapose my skin exam with my tarot reading to highlight peculiarities in Pennsylvania law. In Pennsylvania and a number of other states across the country, fortune-telling is a misdemeanor. Why, in 2025, do we have statutes on fortune-telling? Why is fortune-telling a crime? And what are those laws actually doing?

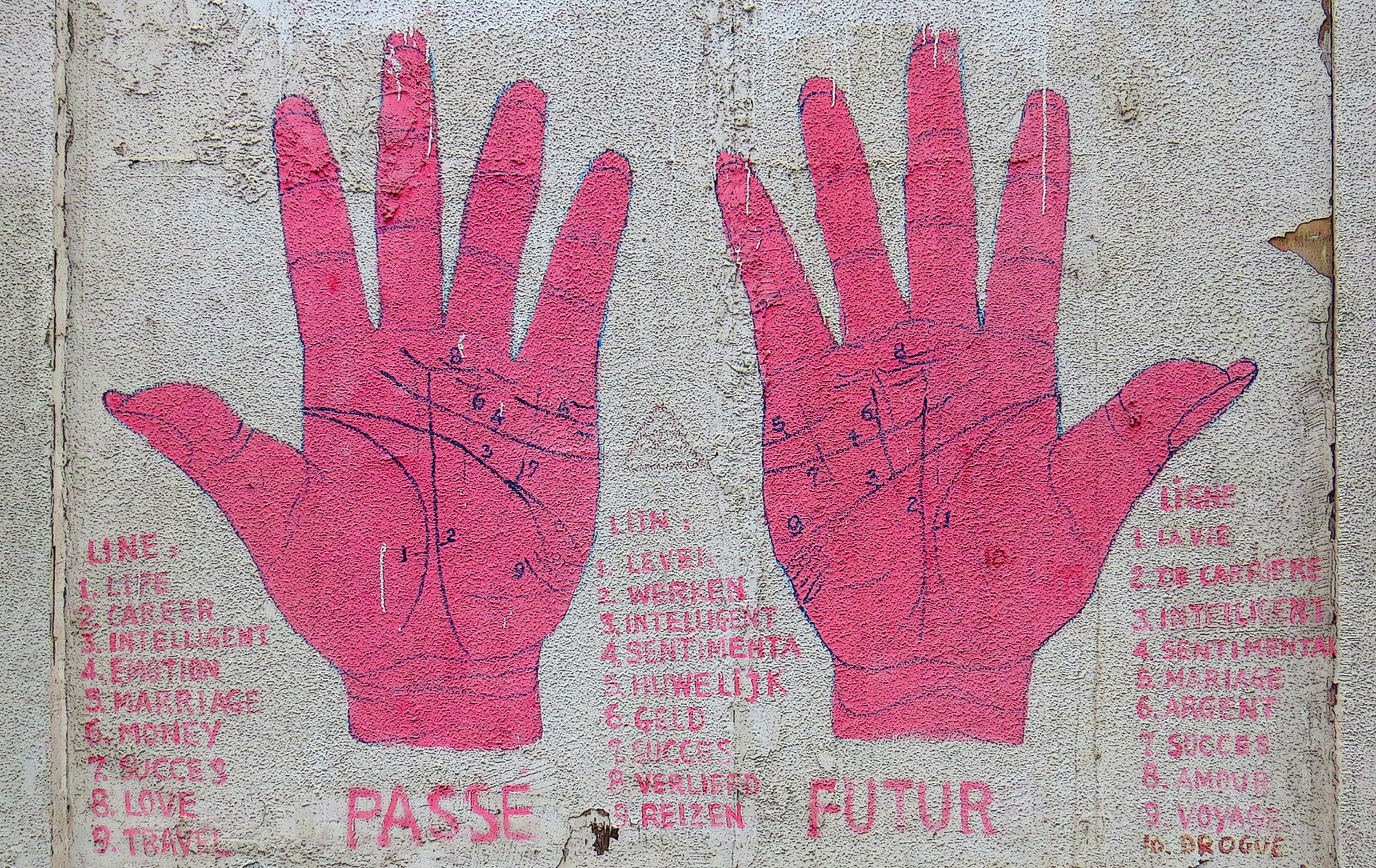

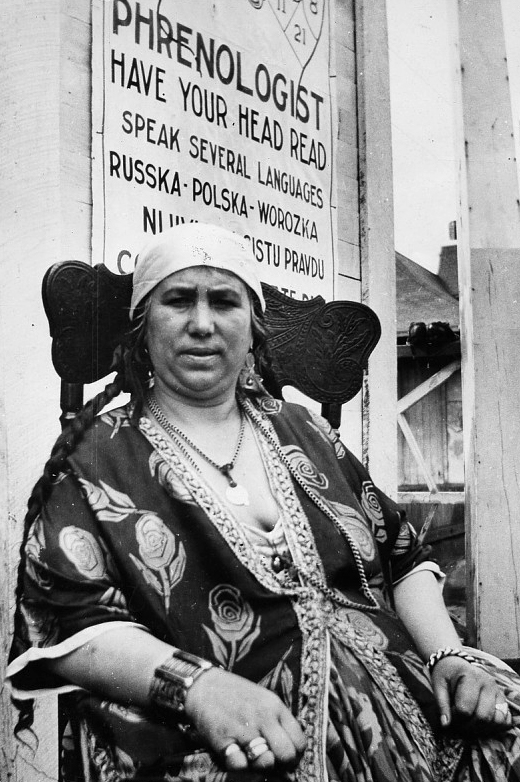

Although Pennsylvania’s statute covers goods and services that today might seem far-fetched—including love potions and necromancy—at its core is a vague notion of “fortune-telling.” Anyone who “pretends for gain or lucre to tell fortunes or predict future events by cards, tokens, the inspection of the head or hands of any person, or by the age of anyone” has committed a crime. What exactly constitutes fortune-telling is unclear, or rather, perhaps so clear as not to need any clarification.

According to a strict interpretation of the statute, Beck’s Celtic cross reading scarcely qualifies as fortune-telling, a key aspect of which seems to be some sort of prediction. By contrast, my dermatologist’s actions seem criminal. He often makes predictions based on the inspection of a patient’s head or hands: this mole poses no threat, that mole could kill you. The accuracy of his predictions is not at issue. And though “lucre” seems to mischaracterize his motives, he certainly makes his predictions for gain.

We can all agree this conclusion is absurd. My dermatologist is not breaking any law. We all know he is not a fortune teller. The university-trained physician who works in a sterile environment, whose demeanor is calculatedly sterile, and who wears a recognizable uniform is not a fortune teller. Our social expectations and assumptions assure us of such.

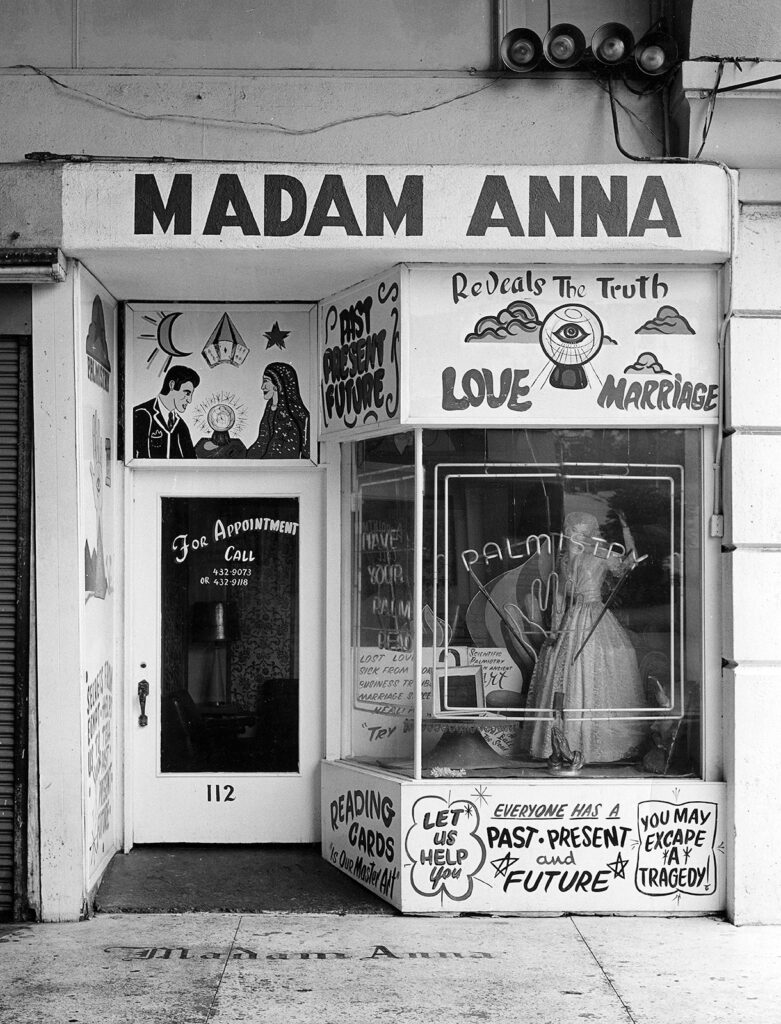

Similarly, our social expectations shape our perception of Beck. They dress as they want. They are interested in their clients as people. They ask personal questions and listen carefully to the answers. Their store is softly lit, warm, and has a pleasant smell. They sit in a comfortable wicker chair and shuffle tarot cards. Though they make no predictions, we know Beck is a fortune teller.