IF YOU COULD TELL people living 5,000 years from now something about our lives here and now, what would you want them to know?

In the summer of 1938, Albert Einstein considered this question earnestly. “We have learned to fly,” he wrote, starting on a hopeful point. Yet “everybody must live in fear of being eliminated from the economic cycle.”

“People living in different countries kill each other at irregular time intervals,” he continued, edging closer to how he had come to be a refugee in the United States. “Anyone who thinks about the future must live in fear and terror.”

Einstein, a pacifist who renounced his German citizenship in 1933 after constant harassment from the Nazis, had spent the intervening years decrying the spread of fascism in Europe, watching with growing horror as scientific ingenuity was pushed to increasingly violent ends. Against this backdrop, Einstein received a request from G. Edward Pendray, assistant to the president of industrial giant Westinghouse, who wanted to send a message to the future.

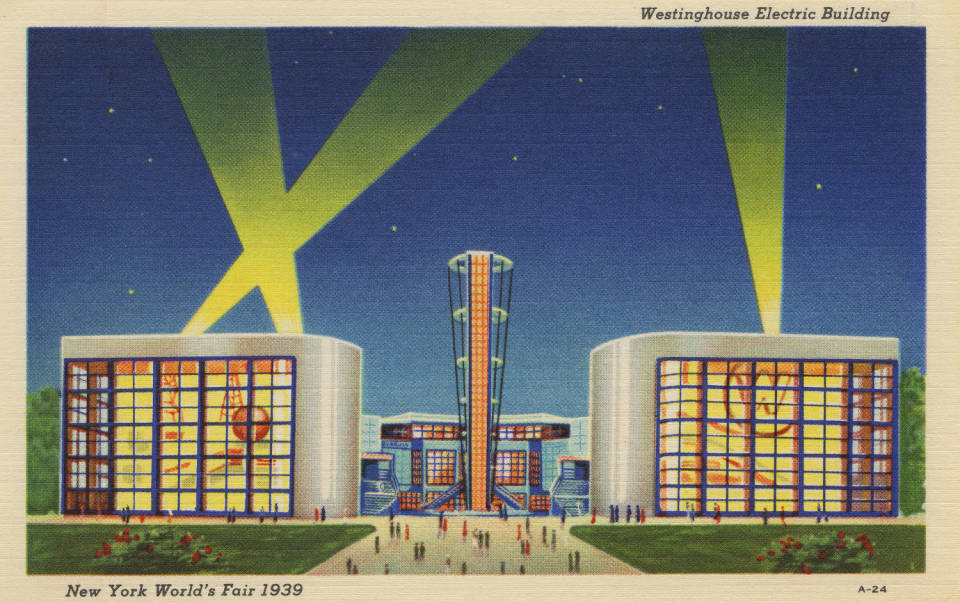

Once upon a time, Westinghouse had bathed the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair in dazzling electric light powered by Nikola Tesla’s then-controversial alternating current system. In the decades that followed, the company unveiled a string of lucrative innovations but still found itself second place in sales and reputation to General Electric—the rival research behemoth founded by Thomas Edison.

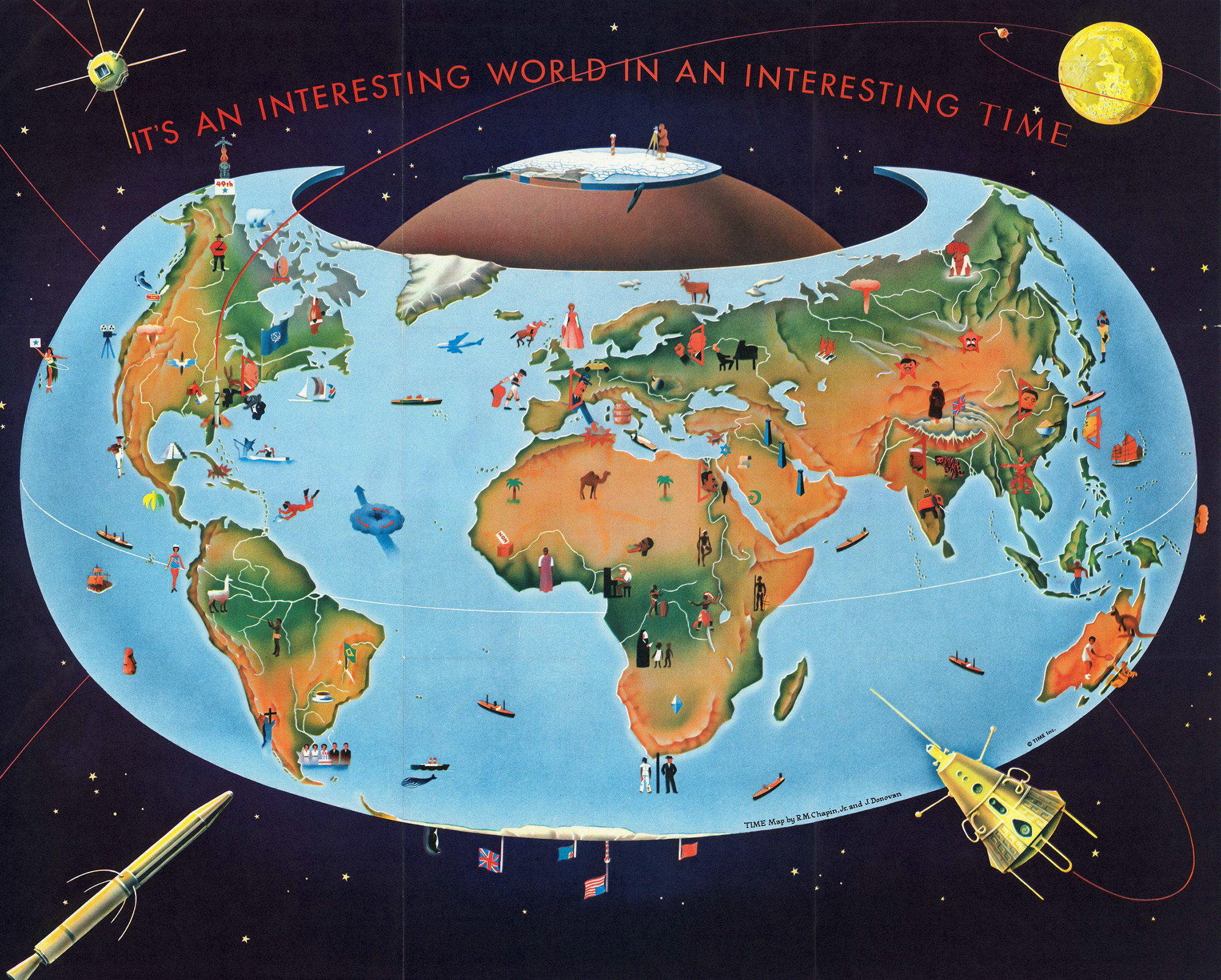

The upcoming 1939 New York World’s Fair promised audiences a peek at “the world of tomorrow,” and offered Westinghouse a fresh opportunity to advance its reputation and sales. The question was what to put in the fair that would show up GE, General Motors, and U.S. Steel, which were all planning pavilions of their own.

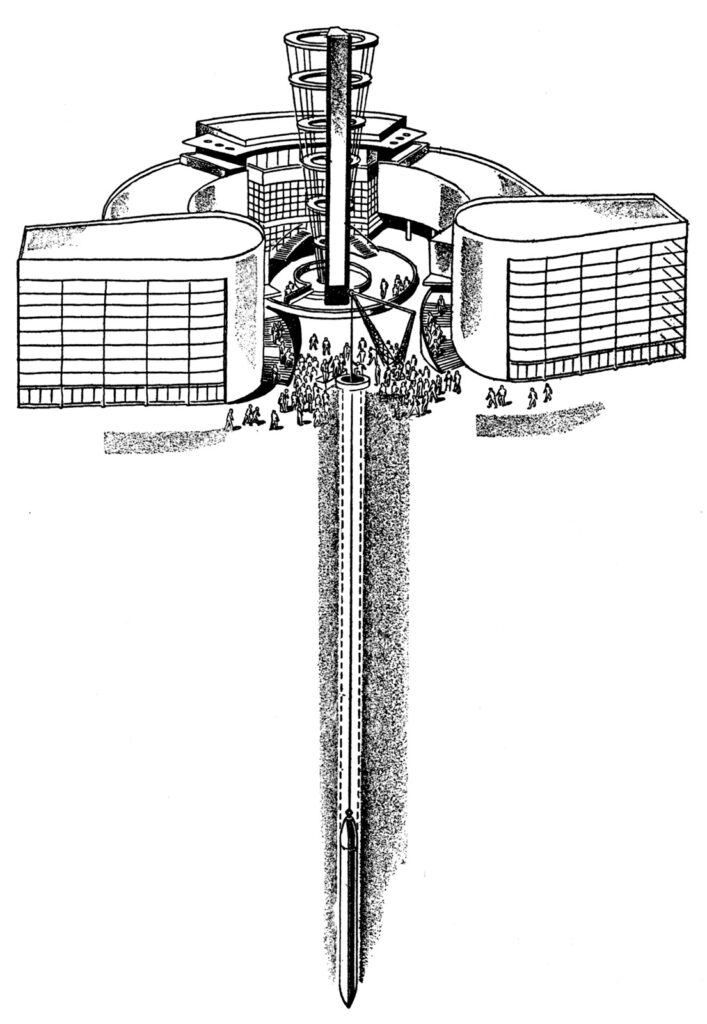

The solution came to Pendray on vacation. A time bomb! They would build a time bomb! A rocket-shaped capsule carrying a payload of all the 1930s had to offer in science, culture, and technology to the distant tomorrow.

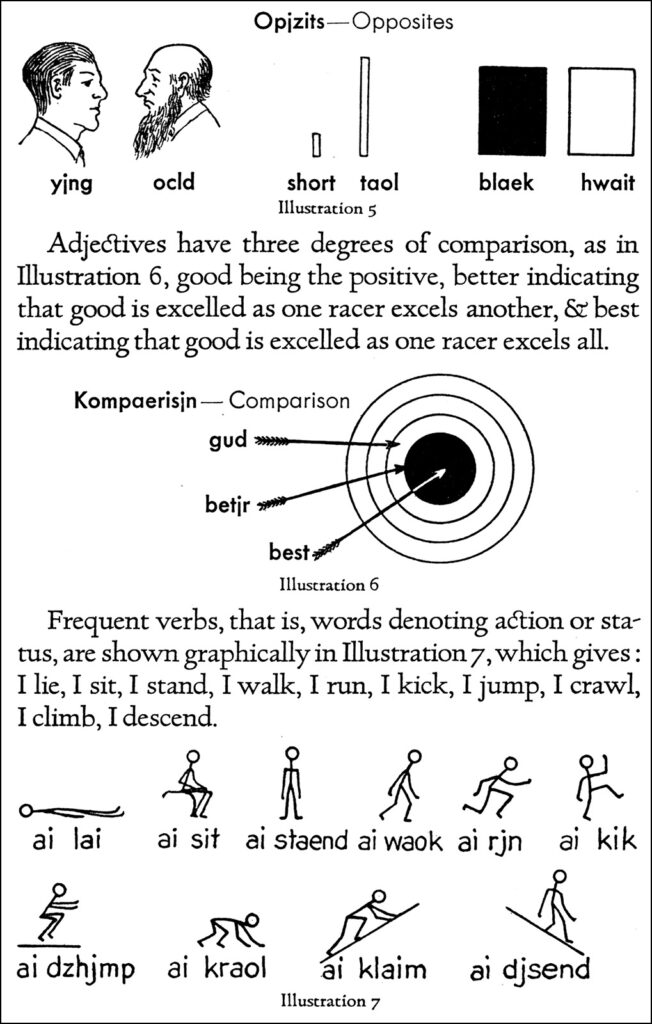

Pendray, a tireless optimist who had founded Westinghouse’s PR department two years earlier, coordinated the whole affair. In less than three months he rounded up a panel of academics to choose objects and texts; recruited a linguist to create tools to help future generations decipher today’s languages; marshaled Westinghouse engineers’ efforts to build a vessel capable of preserving the cargo for 5,000 years; and developed a scheme to ensure people would find the capsule in 6939, buried 50 feet below the Westinghouse pavilion. Years later, he would call that summer’s whirlwind of activity “a kind of religious experience.”

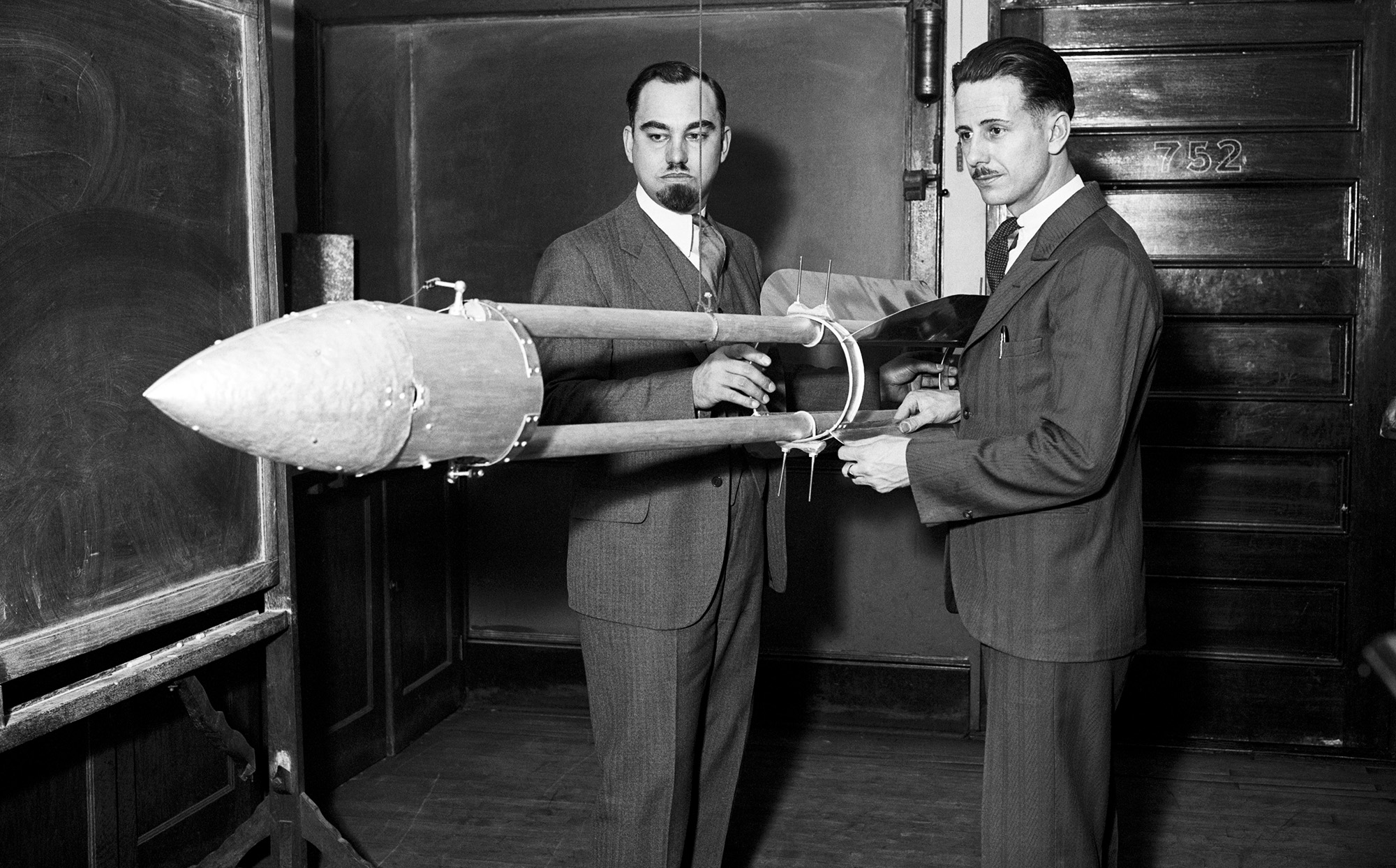

The bomb’s launch was scheduled for September 23, 1938, the autumn equinox. Its final manifest included a Bible; a newsreel with footage of President Roosevelt, Jesse Owens winning the 100-meter dash in the 1936 Olympics, and the 1938 bombing of Canton; a microscope, instructions to build a better microfilm reader, and microfilm containing 1,000 pictures and 10 million words taken from books, articles, and the Encyclopædia Britannica; and more than 110 other objects and materials, including vials holding seeds, a pack of cigarettes, a plastic Mickey Mouse cup, and Einstein’s letter. The entire menagerie was encased in a nitrogen-filled, “torpedo”-shaped housing made of Cupaloy, a corrosion-resistant copper alloy with the mechanical strength of steel recently invented in a Westinghouse lab. By the time it was complete, Pendray had given the bomb its new name—the still rocket-themed, but considerably less violent, Time Capsule.

As a publicity stunt, Pendray and Westinghouse deemed the Time Capsule a tremendous success. By November 1939, it had garnered articles in newspapers and magazines with a combined circulation of 150 million, more than any previous Westinghouse publicity scheme. But Pendray’s affection for the Time Capsule went far beyond the piles of newspaper clippings it generated. When, in 1959, it was suggested that the Time Capsule be dug up early during the 1964 New York World’s Fair, he was aghast.

“I would oppose this suggestion with as much energy as I could muster,” Pendray wrote in a letter to the fair’s chairman. “The Time Capsule project was designed from start to finish as a message about ourselves and our times for the distant future. It is no quickly-put-together stunt, but a project of considerable scientific and engineering importance.”

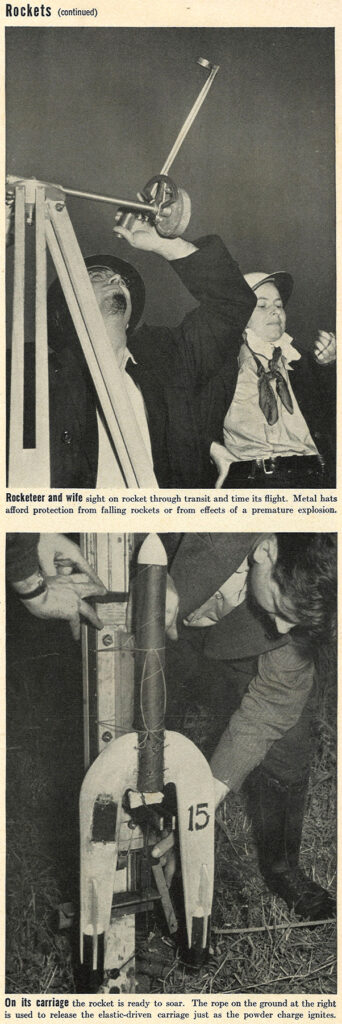

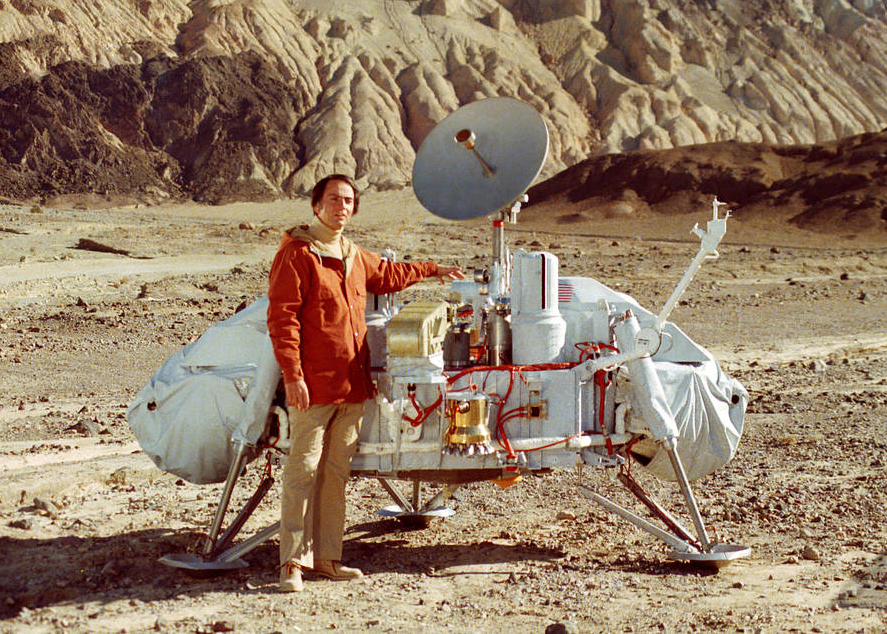

Instead of opening the capsule, Pendray had a suggestion of his own: a second Time Capsule filled with all the advancements made in the intervening years—atomic energy, computers, satellites, and, not least of all, space flight. Pendray had more reason than many to be proud of humanity’s achievements in reaching outer space. He himself had played a notable role in developing the necessary technology.