At first glance, the incident report seems entirely familiar. Upset about the partying in his housing complex, a man alerts authorities that his neighbor keeps getting whacked out on drugs. He gets so high he passes out into a kind of euphoric delirium. Worse yet, he’s peddling the same stuff to other neighbors, who likewise collapse in stupefied ecstasy.

A few details set this tale apart, however. The year is 1640. The authority is the Roman Inquisition. And the whistleblower, dealer, and fellow revelers are all Franciscan brothers living in a friary on the outskirts of Naples.

The anecdote, uncovered from Inquisition archives by University of Chichester historian Lorenza Gianfrancesco, sparks a number of questions. Why were these friars tripping? What were they on? Where did they get it? And how common was this kind of behavior?

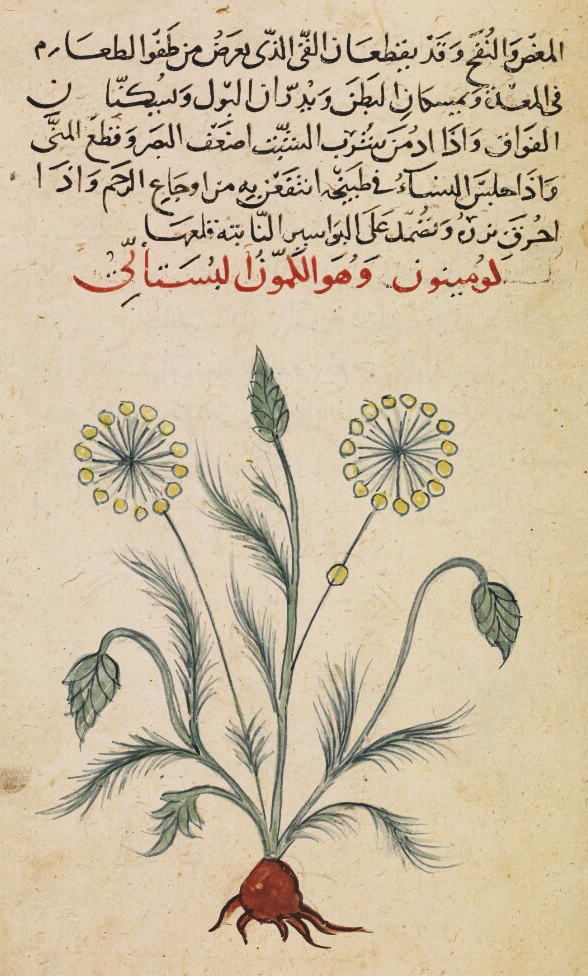

The substance in question, Gianfrancesco believes, was mandrake, a root known for its ability to trigger hallucinations and even comas. And while it’s unclear how common this sort of experimentation was among mendicants in the era, the story underscores a largely forgotten fact:

“In medieval and early modern Europe, chemistry and chemical medicine is dominated by clergy who act as pharmacists and apothecaries,” Gianfrancesco says. Despite the widely held belief that the early modern church was staunchly anti-science—a view epitomized in the 1633 heresy trial of Galileo—Christianity actually was a catalyst for scientific discovery.

“In the Middle Ages, the church was the main supporter and promoter of all science, medicine, and investigative research,” says Winston Black, a professor of history and religious studies at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia. Through the medieval and early modern periods, Europe’s sick and poor turned to church-affiliated pharmacies, hospitals, and, later, chemical laboratories where holy brothers and sisters concocted botanical balms and potions from medicinal herbs grown in the gardens of Catholic living establishments.

Monks, nuns, and friars were not only among the most knowledgeable herbalists and apothecaries in Europe, they were also on the front edge of an intellectual exchange with the Islamic world that ushered in alchemical practices and with them a whole new array of powerful remedies.

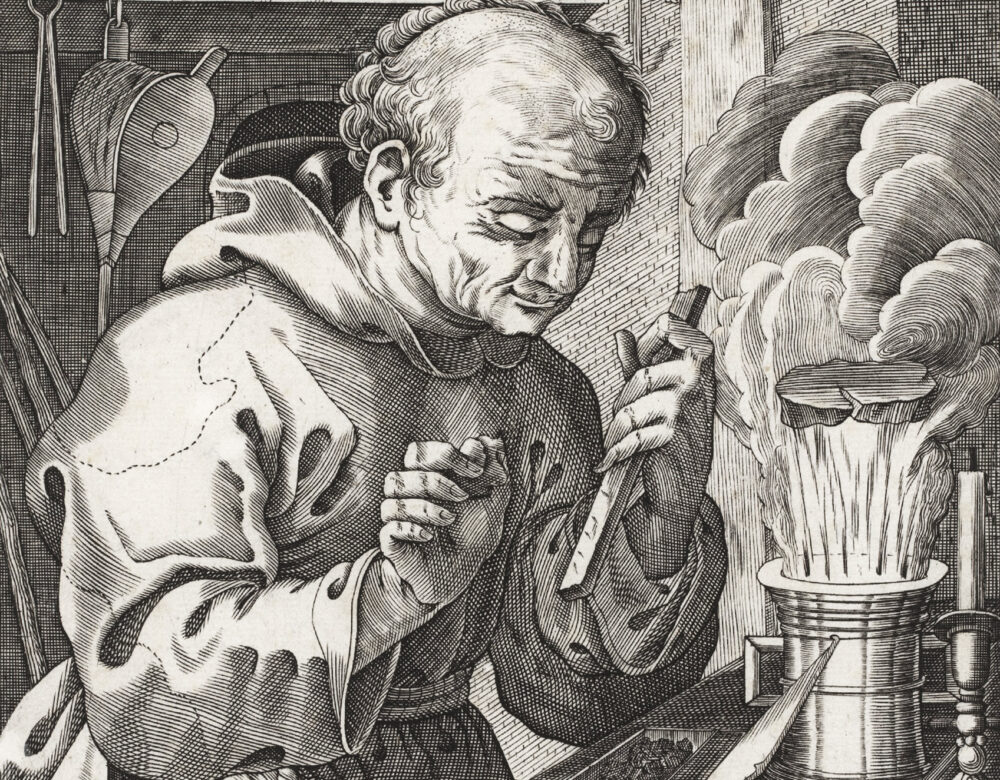

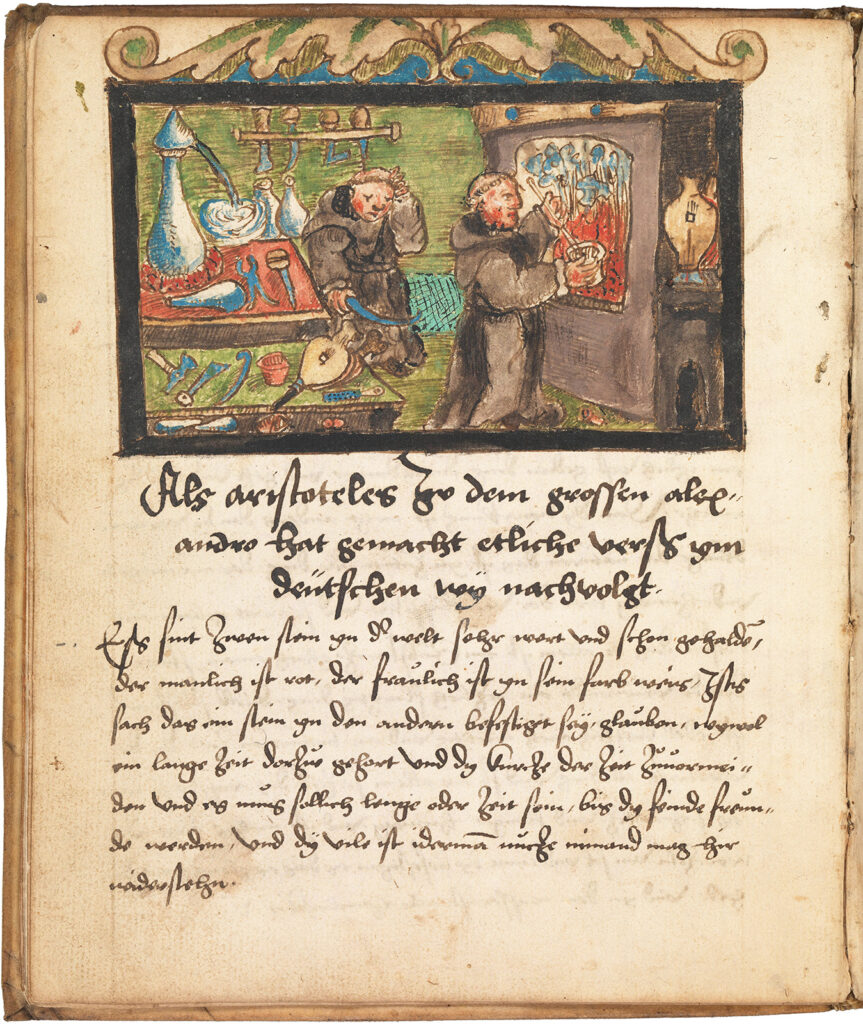

Just as alchemy, long dismissed as magical mumbo jumbo, is increasingly seen as a precursor of chemistry, research is showing that friars played an outsized role in advancing alchemical medicine. Frater medicus, as friar-doctors were called, penned influential books, experimented with new remedies, and peddled potent—sometimes deadly—therapeutics.

It started with monasteries.

The first began to appear in Egypt in the late 3rd century CE, calling Christian men and women to turn their backs on the outside world and live pious, solitary lives of prayer. By cutting ties with their kin, however, monks and nuns lost the foundation of health care: the family. Instead, monastics had to tend to their own, although “the first line of attack wasn’t pharmaceutical—it was diet,” says Andrew Crislip, professor of the history of Christianity at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Beyond prayer, the ill were treated with meat and wine, provisions forbidden to healthy nuns and monks, some of whom feigned illness just to get something hefty to eat. The sick also were given so-called “simples,” teas and tisanes made of a single herb, such as chamomile, marjoram, or mallow.

Botanical medicine at monasteries began blossoming in 529 CE, when Benedict of Nursia, later known as Saint Benedict, founded Monte Cassino, an abbey between Naples and Rome. There he penned what would be known as Benedict’s Rule, which called for obedience, silence, and self-sufficiency among monastics, including growing their own food and medicinal herbs. Sage, rosemary, mint, nettles, and thyme were dried, ground in mortars, macerated, and infused in wine or prepared as poultices and ointments.

Medicinal gardens proliferated among European monasteries, so revered that monks wrote poetry about these salubrious gifts from God. In Hortulus (The Little Garden), 9th-century German Benedictine abbot and poet Walafrid fawns over 24 herbs, recommending celery seeds “to banish the racking pain of a troubled bladder” and the pulp of lily crushed in wine to counter snakebites. In the 12th century Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen wrote Physica, an encyclopedia of 200 botanicals and their therapeutic uses, insight she gained through mystical visions while in the abbey gardens.

“If a person has many lice, let the person smell lavender frequently; the lice will die,” she writes. A paste of nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves should be eaten often, she further advises, to “calm all the bitterness of heart and mind.”

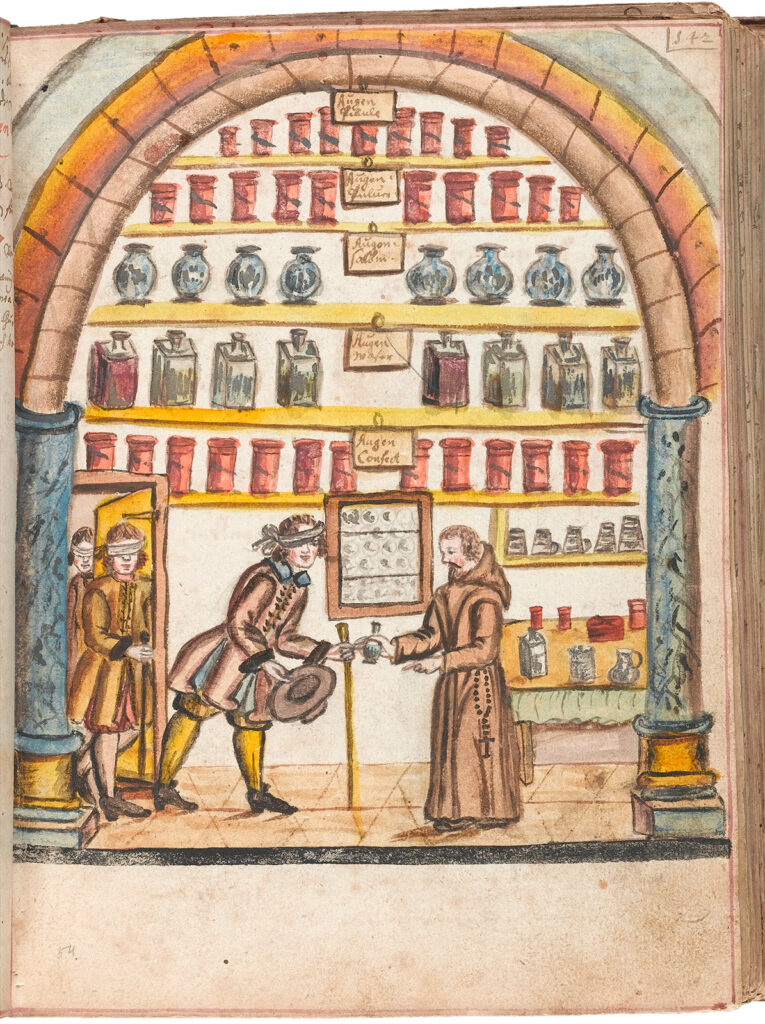

Monasteries compiled such medicinal recipes in their libraries and dispensed remedies to pilgrims and peasants through on-site infirmaries and pharmacies. Eye problem? A salve of garlic, leeks, and cow bile might do the trick. Warts? Try a balm made from willow bark.

But by this point a transformation was underway that would revolutionize monastic therapeutics. The head-on meeting of Christianity and Islam that began in the 11th century brought an influx of Arabic recipes, new ingredients, and alchemical processes that would trigger a medical renaissance.

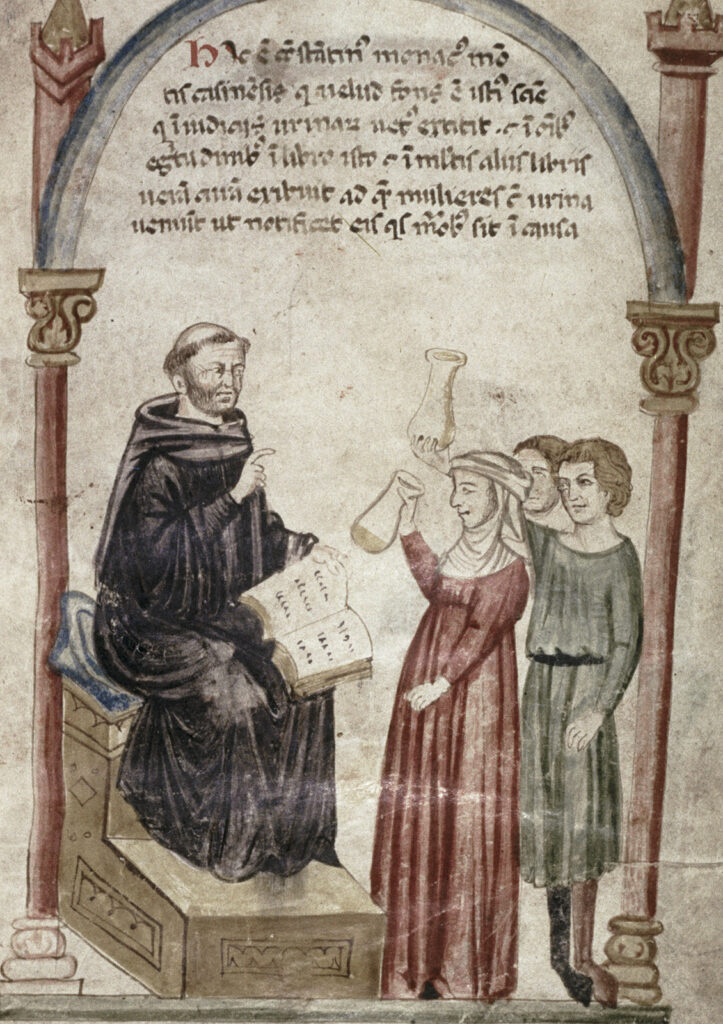

Around 1070, Muslim scholar Constantine the African moved from what is now Tunisia to Salerno, in southern Italy, hauling with him a trove of medical texts written in Arabic.

Constantine’s cache was far more advanced than anything seen by Europeans at the time—it drew from “lost” writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans as well as complex remedies from India and China. Converting to Christianity, Constantine joined the order at Monte Cassino, where he cranked out Latin translations of Galen and Hippocrates and manuscripts on fevers, eye afflictions, internal ailments, surgery, and “tried and true remedies.”

His translations filled Monte Cassino’s library and informed the curriculum at the abbey-affiliated medical school in Salerno, drawing scholars from across Europe. The medical texts introduced previously unknown practices, such as pulse taking and uroscopy; they also fueled demand for rare ingredients used in Islamic medicine, such as ambergris, musk, antimony, camphor, tamarind, cassia, and sugar.

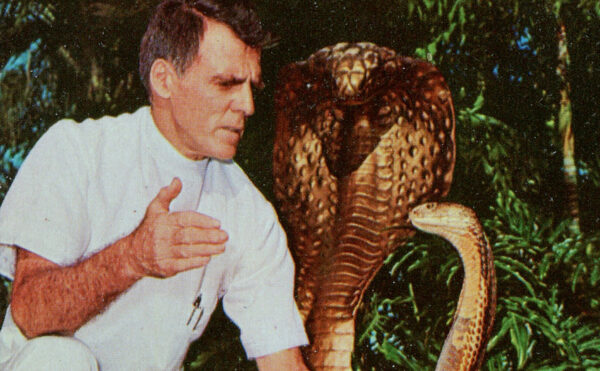

Theriac, a substance used by the ancient Greeks and revived by Constantine’s translations, emerged as the most sought-after curative compounded by monk apothecaries. Mixing viper’s flesh with opium and dozens of ingredients, theriac was heralded as an anti-venom, an antidote to poison, and general cure-all for centuries.

“The reason it was so popular was the opium”—the strongest drug in the medieval arsenal, says Black, author of Medicine and Healing in the Premodern West. However, strength varied, so it “either worked very well or it killed you.” (In either case, the holy brothers had patients covered.)

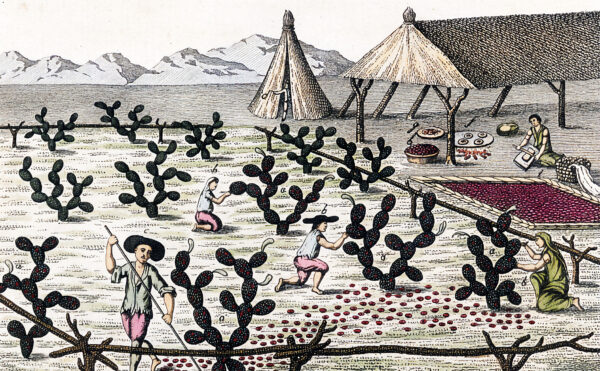

Crusader incursions into the Holy Land starting in 1096 further expanded European exposure to Islamic medical knowledge. These Crusaders encountered more Arabic texts and opened new maritime trade routes that provided greater access to the exotic substances Constantine popularized. Asian plants and spices began making inroads into European kitchens and dispensaries.

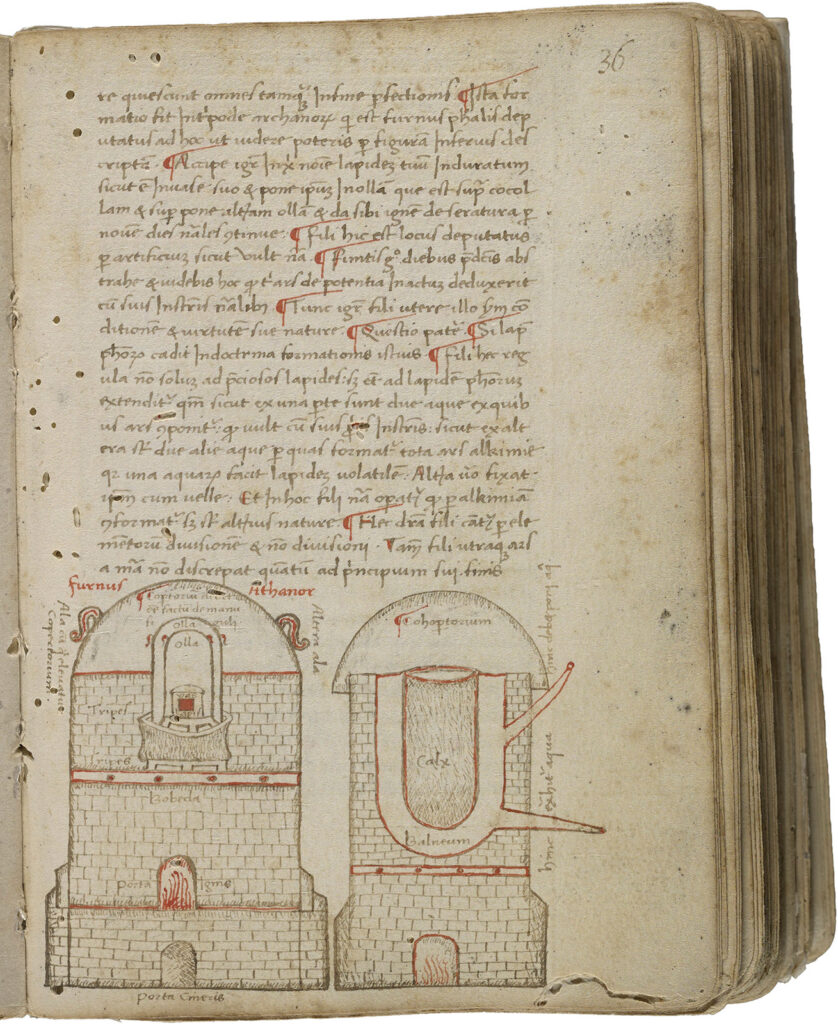

Simultaneously on the other side of the Mediterranean, Muslim control of the Iberian Peninsula was beginning to unravel as Christian warriors reconquered Spanish cities, such as Toledo, a font of Islamic knowledge. In doing so, they uncovered alchemical writings and encountered new instruments, such as alembics used for distillation, although it’s unclear whether they hauled them out of laboratories or discovered them through texts.

Given the geographic proximity, it’s no surprise, then, that European alchemy first took root in northeastern Spain and southwestern France, according to historian Stefania Buosi-Moncunill. And religious houses were a foothold. Alchemical laboratories outfitted with ovens and stills became so common in religious houses that those who wanted to pursue this novel study often signed on with religious orders specifically to do so, says Buosi-Moncunill.

“A monastery provided the perfect solution for alchemical study,” she says, since converts “could access a library, a laboratory, and resources,” including the vast gardens cultivated for drug making.

While some tried to transmute base metals to gold, others tinkered with panaceas to cure all ailments and restore youth. Interest in this new body of knowledge was immense; rulers encouraged these pursuits, even licensing alchemists and dabbling in the practice themselves. This alchemical boom overlapped with a boom in hospital building by religious orders, and the monastic apothecaries attached to these hospitals began to adopt the new alchemical methods and tools.

“In pharmacies and big monasteries, you see this craze for distillation, for trying to get the pure essence of a plant or substance,” says Black. “They called them waters of life, but they’re usually a powerful herbal potion that’s been alchemically distilled.”

Typically starting from a base of distilled wine, these potions (aqua vitae in Latin) often incorporated belladonna, mandrake, and other plants with potent alkaloids. Those alkaloids didn’t necessarily make the elixirs effective treatments, Black says, but they could deliver a punch, and the high alcohol content alone could make people feel better.

Alchemy presented the late-medieval church with all sorts of new conundrums. Were the transmutations alchemy promised credible? If so, were demons involved? And should holy men participate in these activities or condemn them?

Around the same period, a backlash began to emerge that would profoundly affect medicine. At some monasteries, concern grew that monks were spending too much time with outsiders. Shunning the secular world became crucial to the spiritual practice of monks in cloistered orders, such as the Carthusians and Cistercians, that grew in influence in the 12th and 13th centuries, says Black. Their message to the outside community, he says, was “We’re not your hospital, we’re not your guest house, we’re not your library—you stay in your world.”

While these monks were retreating behind monastery walls, another sort of religious figure emerged whose duty it was to go out in the world, spread the gospel, and help the sick and poor—friars. The Franciscan and Dominican orders of friars, founded in the early 13th century, played key roles in furthering alchemy and bringing new remedies to the masses.

Friars and monks are fundamentally different. While both groups take vows of poverty and chastity, their day-to-day activities contrast sharply. Monks are supposed to spend their lives in quiet, secluded contemplation, while friars, humbly garbed in sandals and tunics tied with rope—are meant to live in the world and off the generosity of others.

The mobility of friars and their “freedom from cloistered discipline naturally inclined them toward hands-on healing and experimentation,” says Buosi-Moncunill. “Compared to monks, they were freer, more exposed to real-world needs, and often deeply invested in public health.”

Friars, for instance, tended to lepers and, later, victims of the Black Death, people who were shunned by family, doctors, and society at large. In between hearing confessions and preaching in town squares, some friars also delved into alchemical medicine making.

“Late-medieval friars were among the major researchers into alchemy and alchemical medicine,” says Black. And people of the time, he believes, expected “chemical” knowledge from their frater medicus. Carrying potions and powders in their pouches, friars “replaced monks in the 13th century” as medicine men, says Black. And they became powerful voices on alchemical matters, writing influential books.

Bishop Theodoric Borgognoni, a 13th-century Dominican physician, called for the use of antiseptics and anesthesia before operations in his widely circulated book Cyrurgia (Surgery), which includes alchemical recipes for both.

Franciscan friar and polymath Roger Bacon was commissioned by Pope Clement IV to write books on several subjects, including alchemy and medicine. Around 1267, he sent off Opus tertium, which advocated for the study of practical alchemy in monasteries and friaries as a way to understand nature, produce valuable metals, such as gold and silver, “and discover things which can prolong human life.”

The pope didn’t move on Bacon’s suggestion, dying not long after receiving the book. And soon thereafter, some friaries began clamping down on the practice. Bacon himself was imprisoned for several years, possibly because of his alchemical writings. From 1273 to 1378, six chapters of the Dominican order in France prohibited friars from practicing or teaching the occult art; even ownership of an alchemical book was grounds for excommunication. Franciscan chapters followed with their own bans.

Pope John XXII took a more lenient approach. In 1317 he issued a papal decree banning alchemical gold-making, specifically counterfeiting, while leaving alchemical medicine undisturbed. Nevertheless, alchemy was regarded suspiciously, notably during the tenure of Nicholas Eymerich, Spanish inquisitor general in Aragon during the mid-to-late 1300s. Eymerich regarded alchemy as devil’s work and prosecuted, tortured, and imprisoned suspected alchemists in Spain as heretics and sorcerers.

But friars—a group so associated with rule-breaking, womanizing, and profiteering that they inspired characters by Shakespeare, Chaucer, and Boccaccio—kept bubbling up potions and chasing dreams of transmuted gold. And friars’ reputation for brow-raising behavior wasn’t entirely unearned. In central Spain a group of Franciscans infamously turned a convent into their love nest; their audacious romps and cross-dressing ultimately earned the condemnation of not one, but two popes.

Other friars harbored different obsessions. Fourteenth-century Franciscan alchemist Jean de Roquetaillade (John of Rupescissa) grew increasingly fascinated with boozy elixirs that could cure anything. The key for fully transforming substances and coaxing out their healing essence, he believed, was repeated distillations. Through this refinement, Roquetaillade claimed to have concocted a cure-all aqua vita and devised recipes for the philosophers’ stone and “potable gold,” another panacea made from distilling urine with gold. While Roquetaillade was never punished for his alchemical experiments, per se, his visions and rantings about the end of times and the Antichrist—whose influence could be countered with these magical medicines, he claimed—compelled his superiors to imprison him for decades. He continued experimenting and writing from his cells, perhaps to his own detriment. His recipe for the philosophers’ stone, like many alchemical recipes, calls for the handling of any number of toxic chemicals, including mercury, a poison known to induce hallucinations.

Ravings aside, the sophistication of Roquetaillade’s experiments prompted historian Robert Multhauf to label him a pioneer of medical chemistry in 1954. Roquetaillade’s writings were so popular and well regarded during his own lifetime they inspired a wealthy merchant in Tuscany to form a new order, the Jesuati, in 1360. Becoming a friar himself, the former merchant operated numerous stills to churn out high-octane medicinal waters and opened hospitals across the region to treat victims of plague, smallpox, and typhus. The order became known as the Aquavitae Brothers for the elixirs they handed out. The Jesuatis carried on for 300 years, until Pope Clement IX shut the operation down, purportedly for, you guessed it, bad behavior.

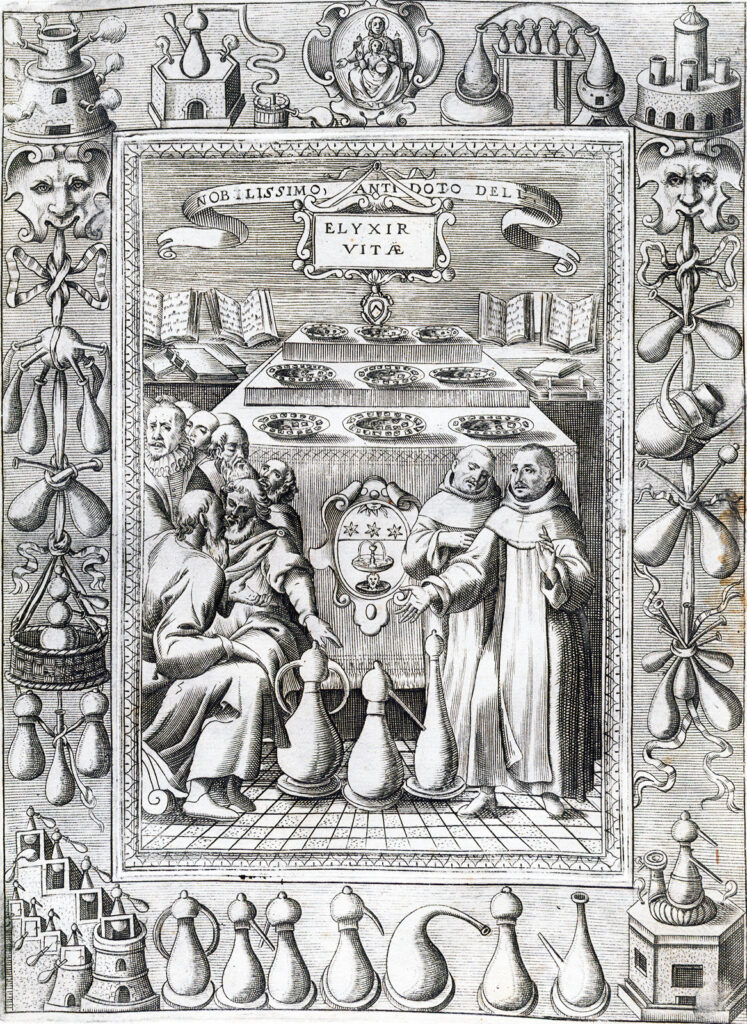

But the public’s thirst for distilled elixirs was far from slaked. In 17th-century Naples, an elixir vitae made by Donato d’Eremita at the Dominican friary Santa Caterina a Formiello was so popular, writes Gianfrancesco, its profits paid to build a museum and library with frescoes wrapping the ceilings and fine art hanging from the walls. Natural philosopher Giambattista della Porta and apothecary Ferrante Imperato, famous for his cabinet of curiosities, were frequent visitors to d’Eremita’s lavish apothecary shop.

Friaries, Gianfrancesco says, “were much more than strictly religious houses. Friars were part of an intellectual network, and they networked with secular patrons. They wrote books. They were part of scientific academies, and the friars traveled and exchanged ideas and know-how.”

But such networks gave pause to some church leaders, who believed friars shouldn’t be so close to money, power, and drugs. When a new prior arrived at the medical center of Santa Caterina a Formiello, he kicked d’Eremita out of the apothecary shop. When d’Eremita protested, his superior locked him up. Distraught, d’Eremita took his own life, almost certainly using a concoction of his own making, says Gianfrancesco.

While his case is extreme, across Europe, pressures were mounting to push friars out of the medical world—both from within the church and without. Mendicant orders, long wary of alchemy in general, discouraged friars from studying medicine or making remedies, which were increasingly viewed as distractions from their primary calling to preach and teach God’s word. Secular physicians, who formed guilds and influenced laws, wanted rid of the competition; they claimed friars were poorly educated in the medical arts.

Meanwhile, the sway of religious houses in Europe was weakening. Protestant reformers saw the establishments as archaic; starting with Henry VIII in 1536, kings shut them down to strangle the church’s power and seize its wealth. During Napoleon’s suppression in the early 1800s, countless monasteries and friaries along with their libraries and apothecary shops—including d’Eremita’s—were dismantled. Chemists replaced friar-alchemists; modern pharmacists replaced monastic apothecaries. Professional physicians became the popular healers. Laws prohibited religious establishments from selling potions marketed as medicine. Holy men were shoved aside and relegated to healing souls, not bodies.

Were the skeptics right? Was monastic medicine little more than hocus pocus, if not the work of the devil? Modern research, at least in some cases, says no. While some remedies—like reciting the gospel over epileptics while dropping hairs from a white dog—sound absurd, other remedies hold up to the test of time.

Multiple studies have suggested some essential oils, including the lavender remedy touted by Hildegard of Bingen, may be as good at killing lice as modern chemicals. Likewise, it’s been a thousand years, and willow bark, or more precisely the salicylic acid extracted from it, remains a frontline treatment against warts. And in 2015 microbiologists at the University of Nottingham, inspired by a medievalist colleague, showed the medieval eye salve made from garlic, leeks, wine, and cow bile could treat bacterial eye infections, such as styes. Tests also demonstrated it was 90% effective at destroying a modern plague—the antibiotic-resistant bacteria MRSA.