On the last day of March in 1953, Enrico Fermi’s phone rang in his office at the University of Chicago. On the line was Francis Loomis, a fellow physicist at the University of Illinois. Given Loomis was the outgoing president of the American Physical Society (APS) and Fermi was the incoming president, they had been in close contact recently.

But Loomis hadn’t called about APS business, or even science. He wanted to talk about a subject Fermi loathed—politics.

Loomis had read a disturbing story in the newspaper that morning. It involved the firing of Allen Astin, the head of a federal science agency called the National Bureau of Standards, or NBS, the precursor of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. By design and tradition, NBS was supposed to be shielded from political machinations. But Astin’s dismissal, Loomis argued, looked blatantly political.

By now, Fermi must have been squirming. Unlike many American scientists who had also fled fascism in Europe, Fermi avoided politics whenever possible. That tendency seemed especially wise in 1953. Several of his colleagues had been dragged into partisan battles over Communism and nuclear weapons recently (battles that would culminate in the notorious Robert Oppenheimer security clearance hearings the following year). Fermi had every reason to hang up the phone as soon as Loomis mentioned politics.

But as Fermi listened, his heart sank. Loomis explained that much more was at stake here than just politics as usual. The dismissal undermined cherished principles of scientific inquiry and freedom. So as much as he hated to, Fermi realized he had no choice but get involved with the bureau’s ugly showdown over AD-X2.

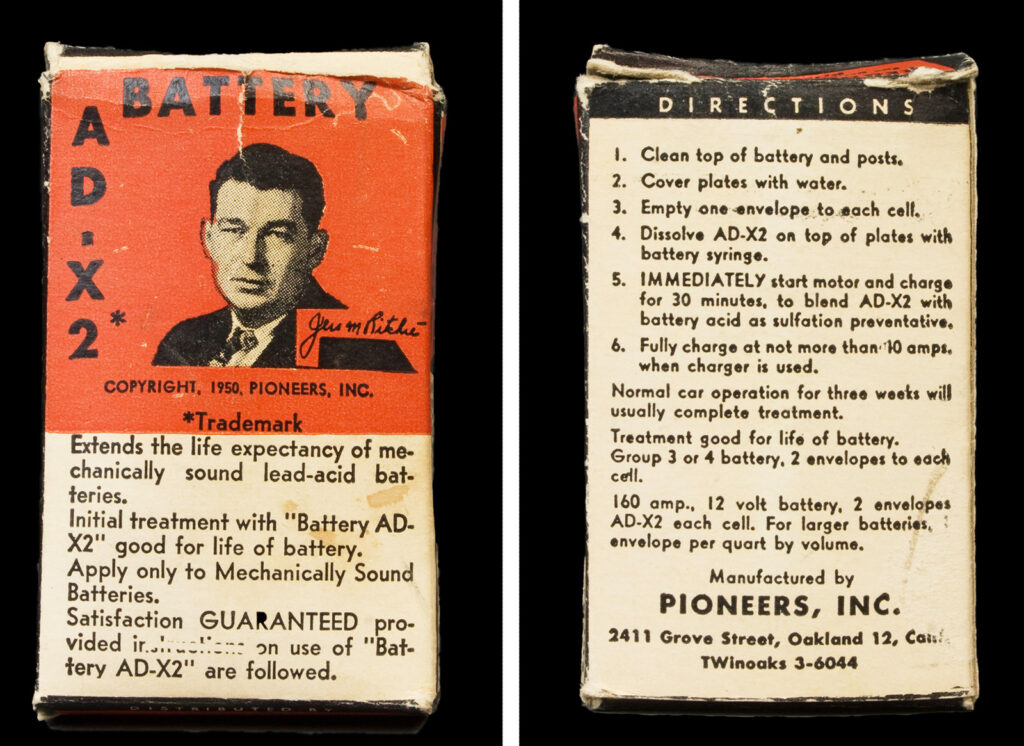

The AD-X2 affair began with Jess Ritchie, a bulldozer operator from Arkansas who dropped out of school after the sixth grade. He later took correspondence courses in engineering and moved to California to work in construction.

After World War II, Ritchie moved to the Philippines as a construction supervisor. He found the job frustrating, in part because his vehicles had constant battery trouble, conking out left and right. When Ritchie returned to Oakland in 1947, he decided to invest in the battery business. He sensed a financial opportunity.

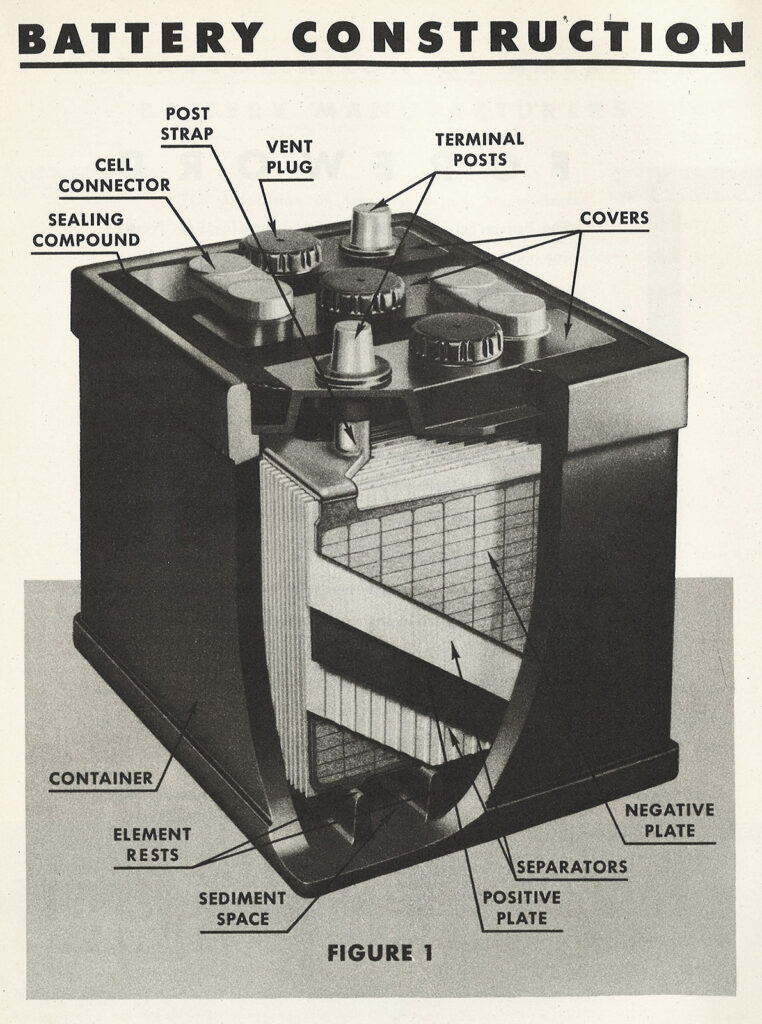

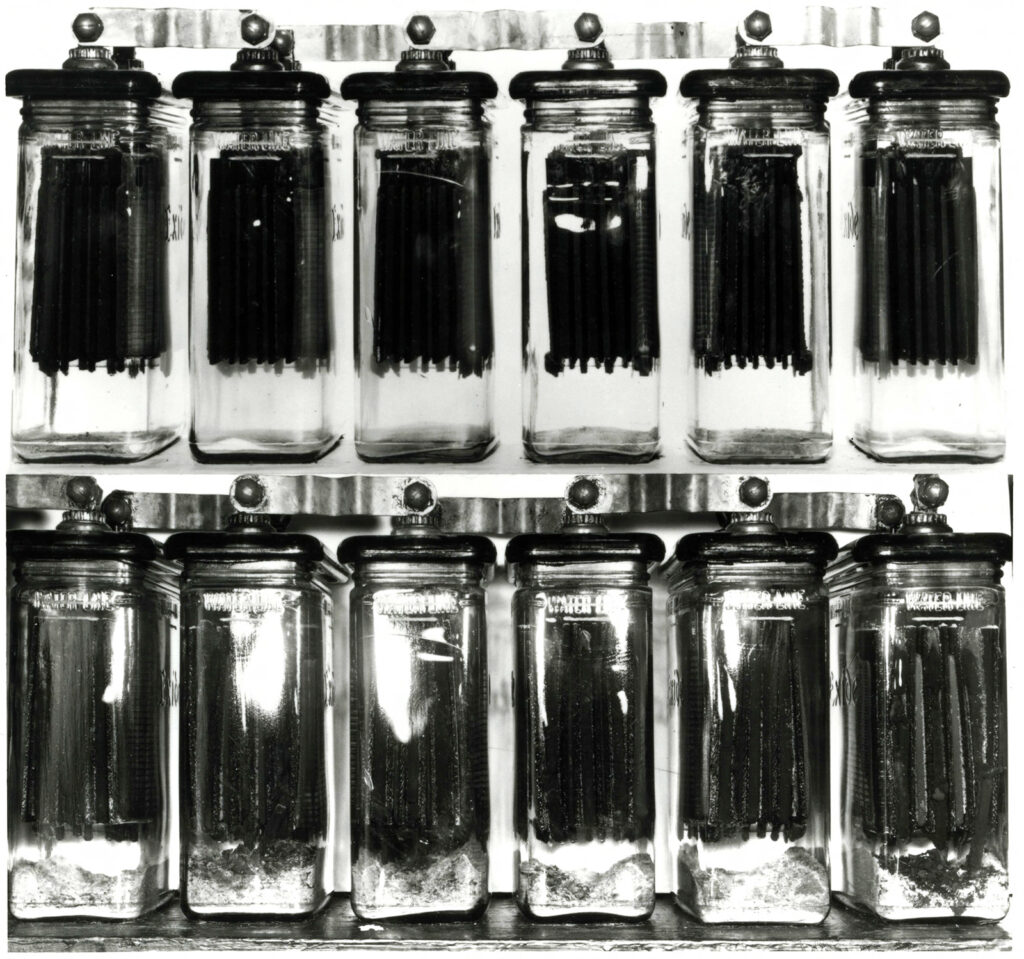

All vehicles made back then used lead-acid batteries, which had a positive plate of lead peroxide and a negative plate of plain lead, both immersed in dilute sulfuric acid. The lead and acid molecules reacted to form lead sulfate and produced electricity in the process. Recharging a battery ran the reaction in reverse.

However, the reaction wasn’t entirely reversible. Over time, a crust of unreactive crystals formed on the plates, leaving fewer molecules available to react and generate electricity. Before long, they crusted over completely, at which point the battery wouldn’t hold a charge—leaving you with a dead battery.

The short lifespan of lead batteries annoyed car owners and industrial outfits, especially since lingering wartime shortages made lead expensive. The United States was also experiencing a postwar boom in demand for cars. All these factors sent the price of batteries skyrocketing. People were desperate to find ways to extend their lifespan.

That’s where Ritchie sensed an opportunity. Various companies sold so-called battery dopes—compounds that promised to extend battery life. In 1947 Ritchie purchased a stake in a company that sold a dope called Protecto-Charge; it consisted of sodium sulfate and magnesium sulfate.

Unfortunately, tests that Ritchie ran on Protecto-Charge revealed that it was a dud. It did nothing to extend the life of batteries and, in fact, seemed to harm them.

Undeterred, Ritchie hired a chemistry professor at the University of California named Merle Randall to help him develop a new battery dope. Under Randall’s guidance, Ritchie ran 1,600 tests on various materials before hitting on a promising compound. He decided not to patent it, preferring to keep its formula a trade secret. He gave it a futuristic name: AD-X2.

Packets cost $3 (around $45 today). As part of normal maintenance, car owners back then regularly removed the lids of their vehicles’ batteries and poured distilled water inside to top off the acid solution. At this point, they could also dump in the crystals of AD-X2. An early ad claimed that it was as easy as dissolving sugar in coffee. Ads also claimed AD-X2 would double or triple a battery’s lifespan, and that Americans collectively could save $360 million per year.

Despite these big claims and heavy advertising, AD-X2 flopped initially. Ritchie was moving just a few thousand packets per month. In talking to mechanics and engineers, he soon realized why—the National Bureau of Standards.

Among other responsibilities, NBS tested consumer products for other government agencies to make sure the products worked as advertised. During World War I, the bureau started testing various battery dopes and found them worthless. It finally issued a circular in 1931 warning consumers against all of them.

That explained AD-X2’s poor sales. So Ritchie got in touch with NBS. He asked the bureau to test his compound and prove it worked.

The bureau declined. According to law, it could test consumer products only at the request of other agencies. Moreover, according to its own policies, the bureau never weighed in on specific brands, just general classes of goods. To do otherwise would risk compromising its impartiality and scientific independence.

These were sensible measures, but you can understand Ritchie’s frustration. NBS had essentially declared his product worthless 16 years before he invented it. It didn’t seem fair.

Ritchie instructed Randall to use his weight as a professor at a prestigious university to pressure NBS to test AD-X2. Meanwhile, Ritchie began complaining loudly that onerous government regulations were squashing a scrappy, hardworking inventor like himself. That message—bureaucracy run amok—always plays well in the United States, and Ritchie soon convinced both the Oakland Better Business Bureau and a U.S. senator from Oakland to put additional pressure on NBS.

To top things off, Ritchie sought endorsements from the military. He offered packets of AD-X2 to five bases in California for mechanics to test on vehicles. Three bases deemed the compound useless, but two said it seemed to work. The tests they ran lacked controls and had small sample sizes, but Ritchie crowed about the results anyway.

Although the bureau’s hands were tied publicly, one chemist there decided to test AD-X2 on his own. His tests showed it didn’t extend battery life. But more troubling, a chemical analysis revealed AD-X2 was nothing but sodium sulfate and magnesium sulfate—the exact same ingredients as Protecto-Charge, a substance Ritchie had already proved didn’t work. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that he was perpetrating a fraud.

Meanwhile, the Federal Trade Commission, which governs advertising in the United States, was growing suspicious of Ritchie’s claims of extending battery life by two or three times. So in early 1950 the FTC formally asked NBS to test AD-X2. At last, the agency had the bureaucratic cover it needed to publish its results on AD-X2. And in an unprecedented move, the bureau broke policy to publicly name a consumer product. In August 1950, it explicitly stated that AD-X2 didn’t work.

A different man might have backed down at this point. Ritchie refused. Although rough around the edges, he possessed considerable charm and soon convinced the science editor at Newsweek to run a gushing story on AD-X2. It cited the endorsement by the military mechanics as well as several happy consumers Ritchie produced. “It is one of those materials,” the story concluded, “that shows up once in a lifetime.” Sales of AD-X2 boomed.

Ritchie also continued to work various politicians, becoming a cause célèbre among pro-business congressmen. Eventually, 28 senators would denounce the NBS results and throw their weight behind Ritchie.

Meanwhile, another political scandal rocked NBS. Its director, nuclear physicist Edward Condon, was hauled before the House Committee on Un-American Activities several times on suspicion of being a Soviet spy. The committee never produced evidence of wrongdoing, but the smears against him threatened the agency’s reputation. Condon made the painful decision to resign.

His replacement was Allen Astin, a quiet, lanky physicist from Utah who had been with the bureau 21 years, mostly working on military projects. However talented a scientist, Astin’s true gift was management, and he had quickly risen through the agency’s ranks. In assuming the position of director in October 1951, he inherited responsibility for the brawl over AD-X2.

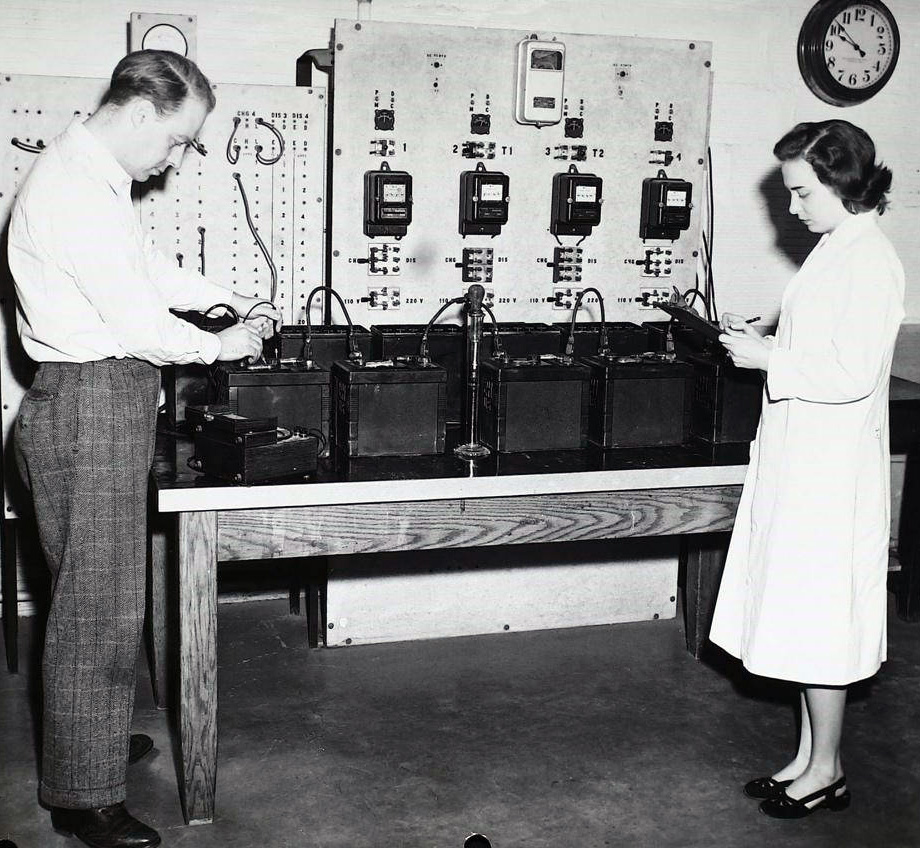

Astin bowed to congressional pressure and reluctantly agreed to Ritchie’s demands for more research on AD-X2. He even asked Ritchie to help design the experiments and agreed to personally supervise the tests.

Unsurprisingly, the bureau once again found AD-X2 didn’t work. And just as predictably, Ritchie rejected the result, claiming NBS had deviated from the agreed-upon protocol. He demanded yet another test, this time by an independent party. He hired a professor of chemical engineering at MIT named Harold Weber to carry it out.

Weber’s tests were odd. For some reason he used very low concentrations of acid, far lower than those found in a real battery. As a result, his findings differed from the bureau’s in a few ways; in his tests, batteries doped with AD-X2 remained cooler during charging, for instance. In his write-up, Weber stressed that these minute differences were probably immaterial to battery performance and lifespan. But scientific duty compelled him to report them.

Ritchie seized on the discrepancies. He leaked the results to his allies in Congress and helped craft a public statement claiming the differences Weber found proved the bureau had bungled its tests and was “psychologically incapable of giving AD-X2 a fair trial.”

The statement blindsided Astin and his staff, in part because they assumed Weber would release the results independently and not slap MIT’s name on the report. They scrambled to analyze Weber’s write-up and catalog the flaws of his experiments. But good science takes time, and Ritchie’s allies had a field day in the interim.

More political wind gathered behind Ritchie’s sails when Republican Dwight Eisenhower won election as president in 1952. By tradition, most agency heads resigned when a new administration took over. A major exception was NBS, a scientific agency that by tradition had remained free from political interference. Astin was a registered Republican anyway and presumably sympathetic. But Eisenhower ran on a pro-business platform, vowing to hack away at the red tape strangling the proverbial little guy. Ritchie’s supposed mistreatment at the hands of NBS bureaucrats fit this narrative perfectly.

Administratively, the bureau was overseen by the Commerce Department, and Ritchie found a keen ally in Eisenhower’s new commerce secretary, Sinclair Weeks. Weeks ran a company that had recently replaced a dead battery for the outrageous cost of $1,300 ($16,000 today). An annoyed Weeks therefore had an axe to grind with battery-makers and anyone seemingly supporting the status quo. (Weeks was also a zealot about government efficiency. In taking over, he demanded a purge of “deadwood and poison ivy” in the federal ranks. He eventually cut 1,900 jobs in the department, and 2,600 more employees resigned.)

In early 1953 Astin tried to meet with Weeks to clear the air about AD-X2. Above all, he sought assurances that Weeks would rebuff the political pressure the bureau was facing to reverse its verdict on the compound. He didn’t want to compromise the agency’s scientific independence or integrity. Instead of meeting with Astin, Weeks pawned him off on an underling. Astin persisted, and Weeks’s office finally reached out with a short message in March 1953: you’re fired. Weeks gave Astin a few weeks to get his affairs in order and clear out.

The dismissal crushed Astin, who had dedicated most of his professional life to the bureau and had never expected to be subject to a political loyalty test. Dozens of reporters clamored to get comments from the deposed director. But Astin couldn’t face them. He holed up in his office and let his phone ring and ring, refusing to answer it.

The moment marked a low point for science’s political standing. Less than a decade earlier, scientists had built an atomic bomb—a stunning technical achievement that, as historian Joseph Martin noted in a study of the AD-X2 affair, “made science politically relevant in ways it had not been before.” But as soon as the U.S. government had the bomb in hand, it disregarded scientists’ advice on deploying it. Most gallingly, in June 1945 several top scientists on the Manhattan Project pleaded with the military to abandon plans for a sneak attack on Japan. They proposed demonstrating the bomb’s power on a remote island first, to give Japan a chance to surrender.

The military, of course, dismissed their advice, and the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki offered a stark reminder of who ultimately controlled scientists’ handiwork. To their humiliation, Martin notes, many researchers who questioned the prevailing hawkish attitudes in Washington found that their “interventions in nuclear politics often exposed their influence as sharply limited.” And things only got worse over the next few years, as scientists such as Condon and Oppenheimer fell afoul of Communist witch hunts.

But when Astin got sacked, the stakes felt different. This wasn’t merely humiliating. Firing someone for producing the “wrong” experimental results—as if nature bowed to the whims of politicians—seemed threatening in a new way, a gross violation of scientific integrity.

So this time, scientists banded together. Individual scientists had always voiced their political beliefs, of course, sometimes passionately. But they had largely resisted organizing as a bloc to promote specific causes—at least until Astin got fired. Martin calls this moment a political “awakening,” as dozens of scientific organizations rallied behind Astin. This included Fermi and Loomis’s APS. Fermi wrote a letter to APS councilmembers to feel out where they stood on involvement. The majority favored action. As one councilmember, Jesse Beams, put it, “I am opposed to the American Physical Society participating in national politics, but the society has always been closely associated with the bureau and I believe that we should go to its aid if we can be of help.” The American Institute of Physics, the American Chemical Society, the Electrochemical Society, and the Federation of American Scientists, among other groups, all felt the same. They issued outraged press releases, and their thousands of members flooded Eisenhower and Weeks with letters.

Then a second, even bigger story broke: 400 NBS scientists were threatening to quit if Astin wasn’t reinstated. This represented more than 10% of the lab workforce. Given how much military testing the bureau did at the time, the walkout would have been a disaster for the Pentagon.

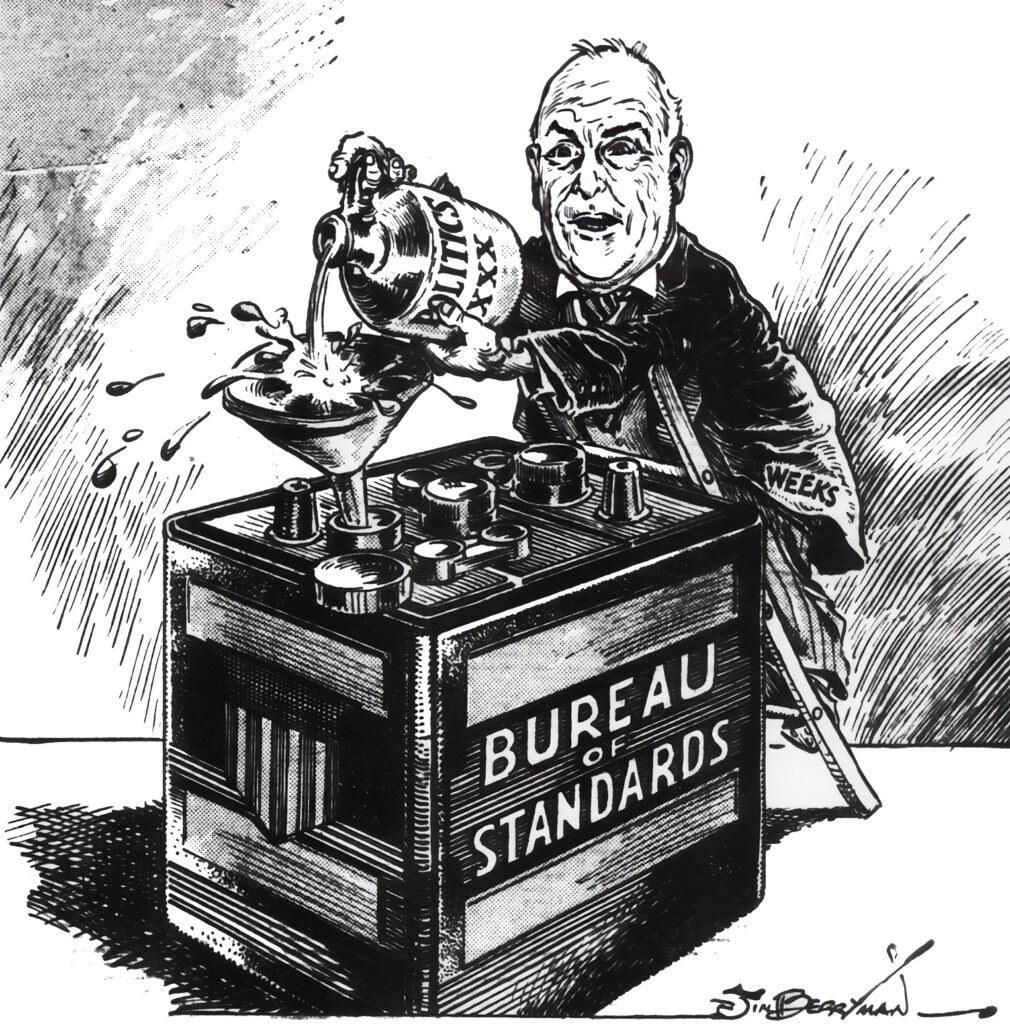

These protests shifted the media narrative as well. Instead of reporters framing this as maverick inventor Ritchie taking on the big, bad government, now they could highlight a noble truthteller standing up to political pressure—another story Americans love. The Washington Post lamented Astin’s shabby treatment, noting that he was “in the best sense of the word a career scientist who has kept wholly aloof from politics and devoted his life to furthering the work of the bureau.” A cartoon in the Washington Evening Star showed a smirking Weeks dumping political moonshine into a battery labeled “Bureau of Standards.”

President Eisenhower—a former general—ordered Weeks to back down. Twelve hours before Astin was scheduled to depart, the commerce secretary crawled back and asked him to stay. To salvage some pride, Weeks made the restoration temporary, pending an investigation by the National Academy of Sciences into the bureau’s handling of AD-X2. Senators would also be allowed to grill Austin. But these rearguard actions failed. The academy report vindicated Astin and the bureau, and the Senate hearing produced only empty grandstanding. Astin won permanent reinstatement.

Over the next few years, sales of AD-X2 cratered. A furious Ritchie later sued the government for $2.4 million, claiming that it had irreparably harmed his business. A judge dismissed the suit. Ritchie went on to run for Congress several times but never won election. He died of a heart attack in 1965 at age 55. Meanwhile, Astin served as director of the National Bureau of Standards for 16 more years. He died in 1984, but as Martin notes, his integrity is still celebrated at the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Although obscure nowadays, the AD-X2 affair marked a turning point for science in Washington. In their protests, scientists had stressed the necessity to remain aloof from politics. But as Martin wryly notes, portraying yourself as apolitical can be a shrewd political move.

And with this newfound confidence, the American scientific community lost at least some of its reticence about messing with politics, especially on the international stage. Meanwhile, the U.S. government took a page from the scientists, co-opting the argument that science had no political ideology, and using that notion to promote foreign aid programs such as Atoms for Peace. By the 1960s, science and scientists were a key component of American foreign policy—a far cry from their impotent attempts to steer atomic bomb policy in prior decades. As Martin concluded, “The impetus for science’s postwar prominence might well have been nuclear, but the quotidian work of securing and exercising its influence was battery powered.”