THE AIR IS WARM AND MUGGY as three volunteers wade into Delaware’s Indian River Bay on a mid-June night. Shin-deep, they lower a square frame made of PVC pipe, called a quadrat, into the water. Their headlamps illuminate a cluster of overlapping round objects in the shallows, like stepping stones dumped in a pile.

“Six, two,” one man announces. Six male horseshoe crabs have crawled on top of two female crabs half-buried beneath them. The females are laying clusters of pinhead-sized eggs in the wet sand; the males are trying to fertilize them.

As Lori Jo Whitehouse, the count leader, records numbers on a spreadsheet, others lift the frame and move down the beach, tallying crabs in one-meter-square sectors. In the biggest cluster, 11 males are jostling to reach two females. “We found the party,” Whitehouse jokes.

Along the shores of Delaware and New Jersey, volunteers are tallying crabs this evening at two dozen sites, extending an annual survey that has run since 1990 to track the crab population in its prime spawning zone. At this beach alone, some nights have yielded more than 400 horseshoe crabs in flagrante delicto.

Horseshoe crabs have inhabited the world’s oceans virtually unchanged for some 450 million years. Genetic studies confirm they are arachnids, more closely related to spiders and scorpions than to true crabs. They were here before trees, flowering plants, or land animals; they have survived asteroid strikes, ice ages, warm eras when palm trees grew in the Arctic, and five mass extinctions.

When the supercontinent Pangaea broke up, horseshoe crabs rode along with the pieces, diversifying into 22 known species around the world. Today four species remain—three in Asia and one in North America, the Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus), which scuttles along the coast from Maine to the Yucatan peninsula. If a horseshoe crab from the Cretaceous period time-traveled to the Delaware shore, it would resemble its modern descendants, with a rounded, helmet-like shell, 10 legs, 10 eyes, 10 gills, and a long, pointed tail. And tonight, it would probably try to mate with them.

Horseshoe crab spawning around Delaware Bay, the estuary that separates Delaware from New Jersey, is one of nature’s great mass events. In May and June, crabs converge on beaches when a full or new moon pulls the tide to its highest point onshore. They leave millions of fertilized eggs buried a few inches deep in the sand. “Witnessing horseshoe crabs mating on a silent beach in spring is like visiting your own private Paleozoic Park,” writes science journalist William Sargent. “Yet this ritual occurs within a hundred miles of every major East Coast city.”

As the crabs spawn, shorebirds are flying around the clock on their migration up the Atlantic coast from South America to summer nesting grounds in the Arctic. Ravenous, they land on beaches to feed—especially on horseshoe crab eggs, which are rich in fat and protein. One closely watched species, the red knot, a plump sandpiper with a reddish breast, is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, its decline partly a consequence of pressure on horseshoe crab populations.

Humans rely on horseshoe crabs too. Commercial fishermen prize them as trap bait for eel and whelk, which are drawn to the crabs’ flesh. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission sets state-by-state quotas for horseshoe crabs caught for bait, partly to ensure there will be enough eggs to feed shorebirds and partly to safeguard their role in protecting human health.

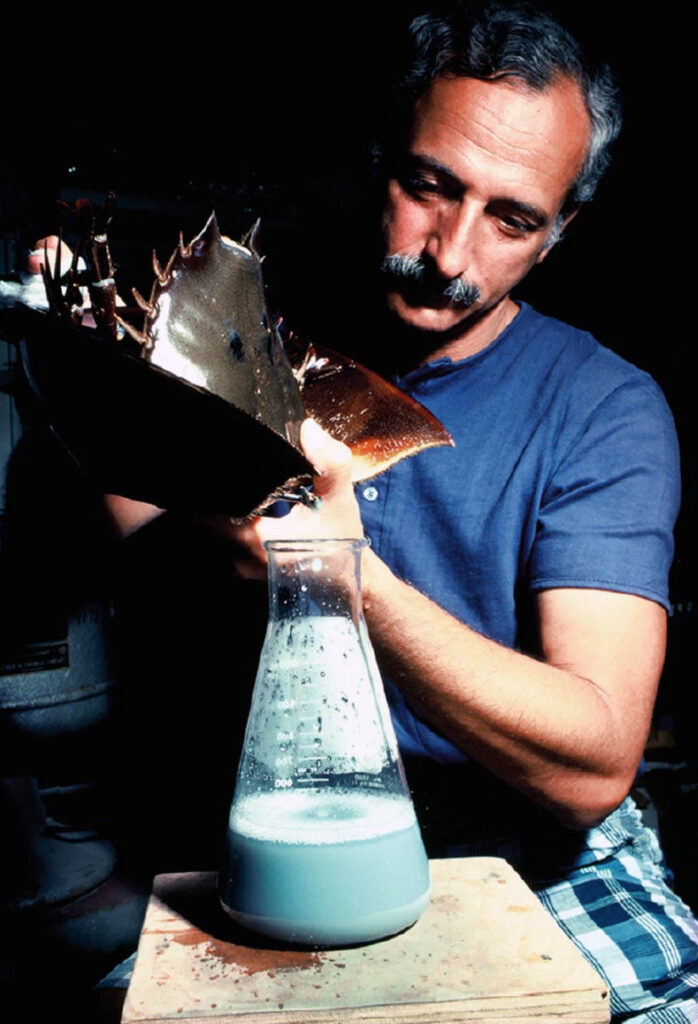

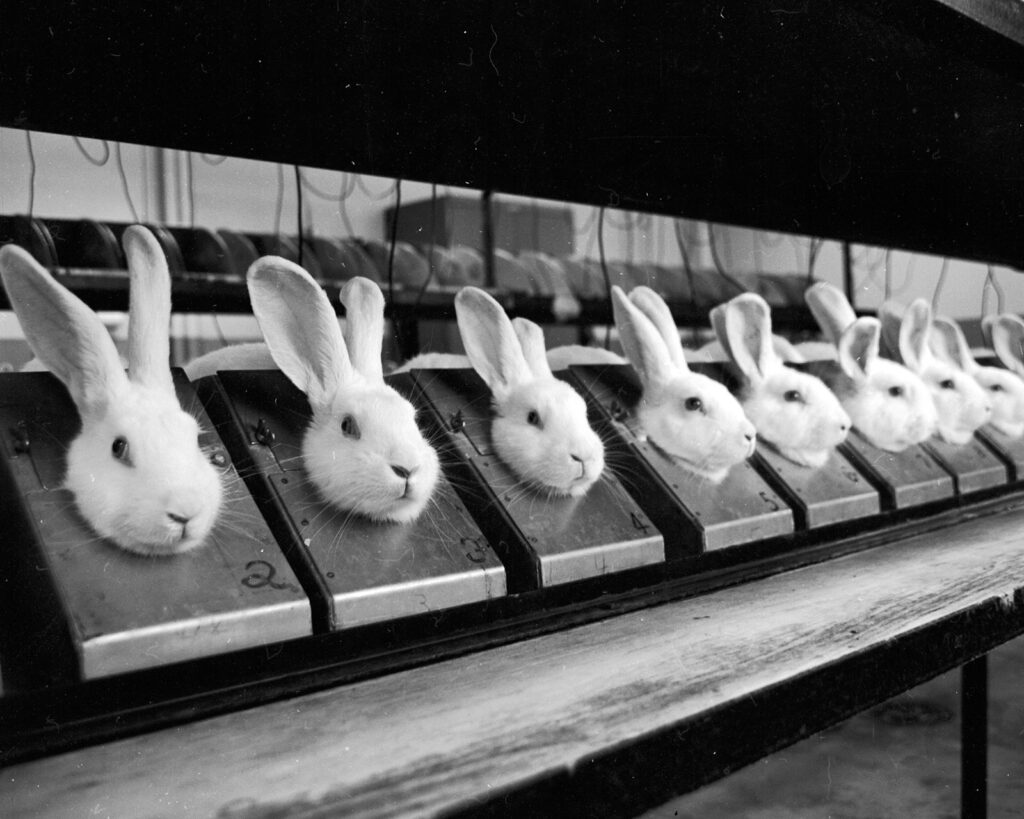

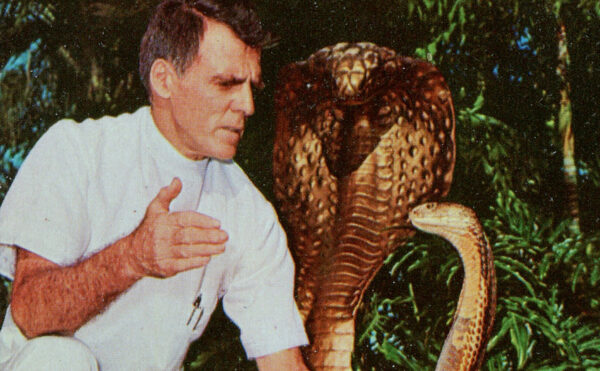

If you’ve ever received a vaccine, injectable drug, or medical implant, thank a crab for ensuring the product is free of contaminants that can cause inflammation, fever, or even death if they enter the bloodstream. The standard test for detecting contamination is derived from horseshoe crab blood. In 2023, the most recent year for which data is available, more than a million crabs were collected for biomedical bleeding.

If all goes well, this harvest does no lasting harm to the crabs. Under best practices, fishermen deliver them to labs that extract up to 30% of their blood then return the crabs to the beaches where they were collected within 36 hours, keeping them cool and moist in transit.

The reality, however, is that many crabs die in the process. And those that survive, many conservationists argue, suffer adverse effects from the experience that could affect the crab’s numbers long term.

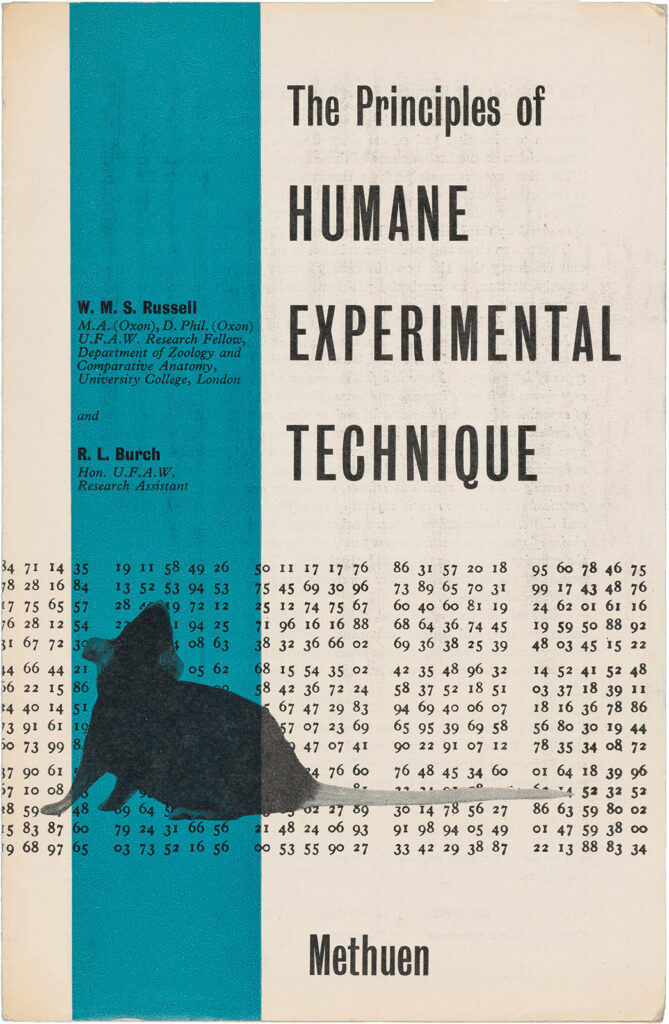

Now change is on the on the horizon: federal agencies have approved synthetic substitutes for crab blood, and some U.S. companies are starting to use them in their testing processes. Depending on how quickly businesses choose to shift, the pharmaceutical industry could help preserve this ancient species instead of threatening its future.