In the 19th century, New York City was an olfactory nightmare. The smells of fish, oysters, and liquor mingled in the streets with the sickly scents of sugar, molasses, and tar. Household garbage festered and putrefied in gutters, while sewers spewed untreated effluent into urban waterways. Slaughterhouses, fat renderers, tanneries, and fertilizer factories all processed animal carcasses and filled the skies with the noxious odors of rotting bodies and burning animal fat. In this reeking atmosphere, the sweetness of flowers and fruit stands provided little relief for residents.

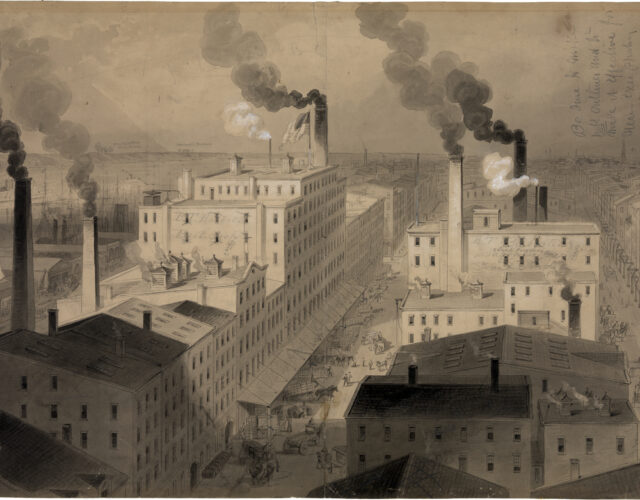

During the 1860s and 1870s New York City experienced unprecedented growth. About 2,000 new buildings were constructed each year, as immigration peaked at 200,000 to 300,000 new arrivals annually. Industries and the wastes they produced multiplied. Smoke was considered a sign of progress, but the intensifying, omnipresent odors signaled a city spinning out of control. People feared that the stinking air poisoned their very bodies, a fear grounded in the medical theories of the day and their own experience of illness. Foul odors were a sure sign of bad air and a pestilential atmosphere, or miasma. New Yorkers reeling from the stink complained to their Board of Health about “the most nauseous, foul, stinking, and pestilential odors.” When the Board of Health failed to control the dangerous aromas, the courts stepped in.

In May 1878 New York City District Attorney Benjamin Phelps indicted the board’s members—scientists and physicians—for “unlawfully, willfully, and contemptuously” neglecting the stench produced by fertilizer manufacturing in Manhattan. After listening to the complaints of citizens a grand jury concluded that the board had neglected its duties and left New Yorkers struggling with headaches, nausea, and insomnia—all the result of city air polluted by foul smells. With summer on the way residents knew that the stench from the slaughterhouses, tanners, and fertilizer manufacturers would only get worse.

How had it come to this? Chemists and regular citizens agreed on the need to regulate noxious industries, yet the city’s residents appeared to be turning on the scientific experts.

At the time he faced the grand jury, Charles Frederick Chandler, president of the Board of Health, was a prominent figure with a long involvement in city government. Born in 1836 and raised in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Chandler completed his chemistry training in Germany. After his return in 1856 he worked as janitor-assistant in analytical chemistry at Union College in Schenectady before moving to New York City in 1864, where he helped found a new School of Mines at Columbia College.

Chandler’s chemical interests included applying chemistry for the public good. He volunteered his chemical-analysis skills on sanitary questions to the newly formed Board of Health and soon attained a regular position as chemist. By 1866, the year of the board’s establishment, sanitary ideals had risen from pre–Civil War obscurity to a matter of national concern. New York City, home of the Sanitary Commission’s founders, was one of the first American cities to establish a permanent and effective Board of Health. Although exactly how diseases were caused remained unknown, sanitarians firmly believed in their ability to prevent stinky miasmas and their consequences—full-blown sickness.

Thus began Chandler’s lifelong professional commitment to public health, over the course of which he would address impurities in city water, adulterated milk and liquor, dangerous kerosene, poisonous cosmetics, tenement house construction, plumbing and house drainage, summer epidemics, and the care of contagious diseases.

Chandler also committed himself to establishing chemistry as a professional field in the United States. He chaired the 1874 Priestley Centennial, the first national gathering of chemists in the United States, and took up the suggestion of creating a national professional society for chemists independent of the overarching American Association for the Advancement of Science. Chandler then publicized this idea in the pages of American Chemist, a journal he created and edited, and later served twice as president of the new organization, the American Chemical Society.

For many in New York City, Chandler, with his distinctive mustache, was the face of both public health and chemistry. Those who questioned his expertise in policy thus also challenged his scientific knowledge. Mounting complaints about New York City’s stenches in the 1870s proved a trial for Chandler as both chemist and public servant. New York Times editors claimed that the board’s members “secretly removed their [noses] long ago, and have since been unable to perceive any bad smells.” In the Ohio Medical Journal a letter writer renamed Chandler’s group “Board of Death” and denounced this “negligent, pretending, and worthless Board” because “the most nauseous, foul, stinking, and pestilential odors still permeate the atmosphere of this overtaxed city!”

Since its inception the Board of Health had pursued odor regulation by restricting the locations and practices of such offensive trades as slaughterers. The board pushed slaughterhouses north of 40th Street in 1868 and then banned them altogether from between 40th Street and the core of the city in 1870. (The board acted again in 1885, confining slaughterhouses to a narrow block between the Hudson River and Eleventh Avenue from 39th to 40th Street.) Similarly, the board demanded that “scavengers,” the people who emptied cesspools, collected offal, and cleaned stables, do their work at night, use disinfectants, and immediately move offensive material out of “the built-up portions” of the city. The board designed a system of permits that governed both scavengers and the offensive trades and created sanitary inspectors to enforce these regulations. Overall, New York City’s Board of Health tried to eliminate odors by banishing their sources to the edges of the city, far from homes and nonindustrial businesses.

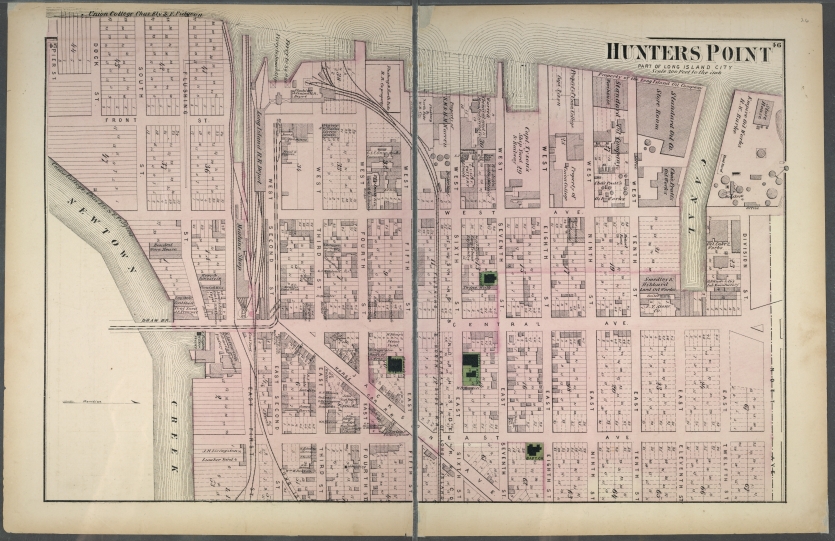

Manhattan businesses began to move across the East River to Kings and Queens counties. At Hunter’s Point, where urban boosters actively courted new development, and along Newtown Creek, the natural border between the two counties, business owners found their ideal: relatively lax health boards, water access for trade, and proximity to a dense working population. The offensive trades anchored miles of interdependent factories that spewed stench and smoke along the creek’s banks. Chemical factories produced sulfuric acid, which oil refineries mixed with petroleum to remove impurities. After agitating the mixture with an air jet, workers drew off “sludge acid,” a compound of spent acid and contaminants, and sold this waste to nearby fertilizer manufacturers. Any of the black and foul-smelling stuff that remained unsold was dumped into Newtown Creek, a tidal waterway. At each return of the tides, the sludge acid released more fumes.

Fertilizer manufacturers spread sludge acid over carcasses and left them in the sun to rot. Sludge acid sped decomposition, releasing pungent and irritating fumes, particularly as days grew warmer. Easterly winds carried the distinctive odors of sludge acid and animal putrefaction across the East River to Manhattan. Gas works added to the nasal cocktail. City lights burned natural gas purified by a dry-lime process that produced sulphureted hydrogen and sulfide of ammonium. These gases diffused over a wide distance, infiltrating Manhattan’s homes as easterly breezes carried the odors across the river and into the heart of midtown.

The Board of Health’s repeated failures to provide olfactory relief to residents and to protect their health led to Chandler’s 1878 legal challenge. Board members, now on the defensive, parsed, for all who would listen, the different odors of sludge acid and other smells. As board president and a trained chemist, Chandler led the education effort. In courtrooms, in conversations with the press, and before his professional peers Chandler insisted that “sludge acid” caused the physical discomfort and complaints of the previous summer, not any factory operating within Manhattan and the board’s jurisdiction. When subpoenaed, board members appeared with maps and charts to explain how the wind conveyed the distinctive stench of oil refining from distant Brooklyn plants to midtown. Before the Medical Society of the County of New York, Chandler recounted how the Board of Health had banished bad smells from the city and claimed that “having eliminated all other smells, [the board] has uncovered this one [sludge acid].” Playing on his professional credentials, Chandler went on to say that the odor of sludge acid “is one that cannot be mistaken by a chemist.”

While Chandler attacked his opponents for their “selfish personal ends”—looking out for their own property values and political ambitions—his complaint against lay sanitarians ran deeper than corruption. Some time after the trial Chandler told a reporter: “The trouble is that citizens are very poor smell detectives. They are annoyed by a stench and in most instances ascribe it to some industry near them and believe it to be perpetual.” Chandler thought that amateur sanitarians, such as vocal and critical members of a local citizens’ group were “to the professional and official sanitarians what a horde of ambitious and officious guerillas would be to a General of an army at a critical moment. They insist on thrusting forward theories and advice and acting independently . . . while they are unable to render any real service.”

Chandler could not stop New Yorkers from sniffing and complaining, but he hoped to harness them to his purposes by setting up a chain of command for individual complaints. A year after the court case of 1878 he deputized his former student, chemist Samuel Goldschmidt, as Inspector of Offensive Trades, with the power to stop offending practices. Goldschmidt’s experiences as a fertilizer inspector in Savannah had turned his nose into an instrument that could tease apart smells, whether from organic decomposition or from chemical waste. As inspector, Goldschmidt spent his days monitoring the winds and inspecting the practices of New York slaughterhouses, gas works, fat renderers, fertilizer manufacturers, and other redolent businesses. He remained on call at night, when perturbed citizens might arrive on his doorstep and drag him out into the dark city streets to track down a disgusting smell.

One nighttime visitor demanded that the inspector identify a nuisance that kept him from sleeping. Goldschmidt later reported that the stink had died away and likely came from across the river, beyond his jurisdiction. Just like the air and breezes that carried them, odors were ephemeral. Their constant arrivals, mixtures, shifts, and departures were well-known but still problematic for the trained chemist: “The wind was blowing strongly from the East North East, and by careful watching mingled with the Hunter’s Point smell, could be obtained slight puffs from the manure and garbage dumps, and the slaughter house smell. About 9:50 came for a few moments the rendering odors, and this gradually died away.” Tracking all the odors in this ever-changing nasal cocktail proved surprisingly difficult. Goldschmidt focused on the rendering odors but could not determine whether they came from a rendering tank at Rafferty and Williams or a malfunctioning condenser at Schwarzschild and Sulzberger, so he cited both companies

When Goldschmidt submitted his reports to Chandler, he noted two types of stenches: those he abated and those beyond his control. Chandler, whose regulatory concerns extended beyond the city, was keenly interested in both. Because New York’s stenches often traveled with the wind, Chandler hoped to create a new organization through which he could control industries upwind of the city.

When the New York State Board of Health formed in 1880, Chandler finally had the power to deal with Hunter’s Point. At the first quarterly meeting of the state board, Chandler introduced the first item of business: “Resolved—That a special committee be appointed by the chair to proceed to New York City to take testimony with regard to the nuisances alleged to exist there.”

The Special Committee on Effluvium Nuisances gave Chandler new jurisdiction over New York City’s air and gave the citizens of New York a new audience for their complaints—and a new scapegoat for their disappointments.

The Special Committee consisted of three men: Albany doctor J. Savage Delavan, whom Chandler had known since teaching at Union College; state senator Erastus Brooks, who had owned and edited the New-York Express; and Elisha Harris, New York City’s well-known sanitarian and vital-statistics registrar as well as secretary of the State Board of Health. This committee gathered testimony about the odors from New York’s professional and amateur sanitarians. Doctors commented on the health problems associated with the stenches, such as headaches, nausea, and depression. Laypersons from the fashionable, wealthy, and politically connected Murray Hill neighborhood (residents included the Astors) testified to their own discomfort. A Mr. Montgomery put it plainly when he said, “The stench was simply terrible. It could not be described, but must be smelled to be appreciated. . . . I have been broken of my rest night after night in the Summer, . . . until I was nearly sick and unfit for business. There is no alternative but to open the windows and let in the stench or close the windows and suffocate.”

Montgomery’s neighbors seconded his comments. George G. DeWitt said the odors depressed spirits and robbed people of their appetites. Henry Bergh said the odors caused intense discomfort, if not outright sickness. Bergh also insisted, like Montgomery, that these stenches needed to be experienced to be understood: “It is impossible to describe the perfume of the rose, and equally impossible to describe the detestable odors of Hunter’s Point.” Throughout the testimony about stenches and illness ran one insistent refrain: if the members of this new committee wanted to understand the odors, they had to smell and experience them for themselves.

The committee decided to make a tour of inspection. They put their noses to the wind and went in search of the stenches’ sources. A New York Times reporter used heavy sarcasm in recording the experience of these three men encountering the powerful, but commonplace, odors: “The homes of these [sickening stenches] are along the shores of the East River, and by dodging in and out of slips with a tug-boat, and by creeping and climbing over oil-lighters and rotten string-pieces, they were finally reached by the committeemen without loss of life or limb.” Though the men were safe for the moment, things changed when the state officials found “the home of the most powerful stench of the day. . . . Assemblyman Brooks started as if a knife had pierced him after taking one whiff. The other members of the party were visibly affected.” This powerful stench emanated from a fertilizer factory, which used sludge acid.

The state intervened at last, ordering that the cause of the stinks be removed by June 1, 1881. In the end, more than any catalogue of testimony or chemical reports, the committee members’ own noses and turned stomachs convinced them of what everyone had been saying: the state government must intervene to control noxious odors from Kings and Queens counties that drifted into New York. While chemists had a place in the final report presented at Albany, the evidence that spoke most forcefully was not their research and opinions but the experiences of multiple New Yorkers and of the committee members themselves. Yet chemists did play an important role in the politics of regulation. They established the validity of complaints and were the “smell detectives” whose professional training qualified them to track smells to their sources. Ultimately, though, neither chemical reports nor individual complaints created air regulation: politicians heeded chemists and complainers only when odors were linked to consequences of political importance, such as powerful citizens and voting blocs.

Though citizens continued to complain of noxious odors after the governor’s 1881 ordinance, their complaints were now channeled through a political system of citizen reporting, scientific investigation, and official response. Rather than oppose each other in the courts, chemists and concerned citizens worked together in the streets, gradually shifting their concerns from stinks to smoke—a far more visible target, and one that was morphing from a sign of progress into a health hazard. Drawing on their earlier experiences, chemists and citizens campaigned together against the new threat.