Only once have I had to use a pallet jack and the freight elevator to bring in a new acquisition for the rare book collection. It was in 2015 when the Science History Institute acquired a complete run of the Annales de chimie, from its founding in 1789 through its eighth series ending in 1913. The 401 volumes came in one giant crate (that my kids later made a fort out of).

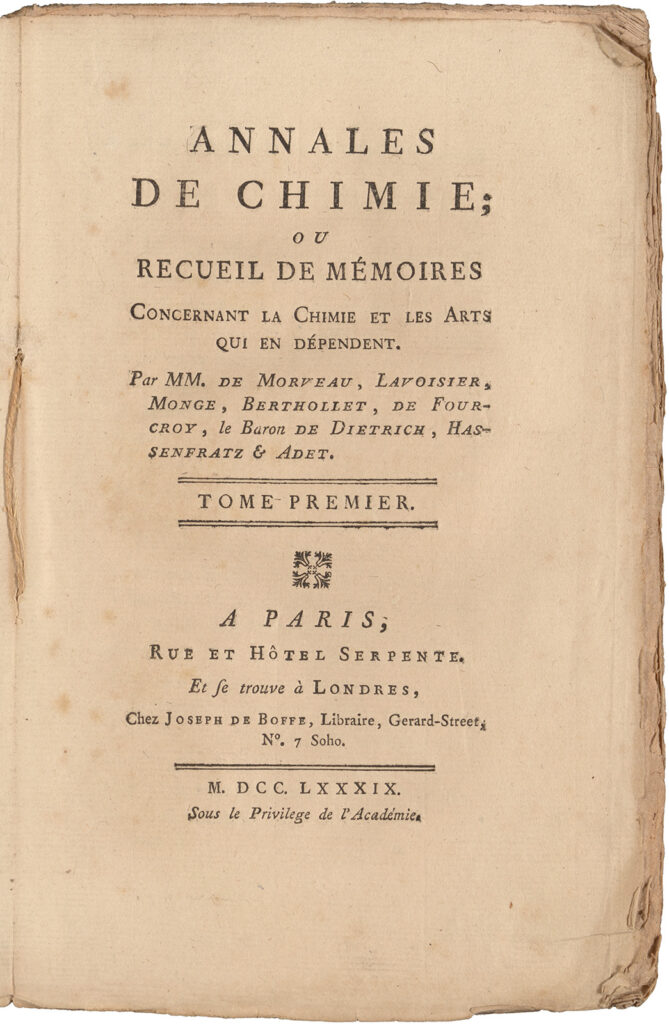

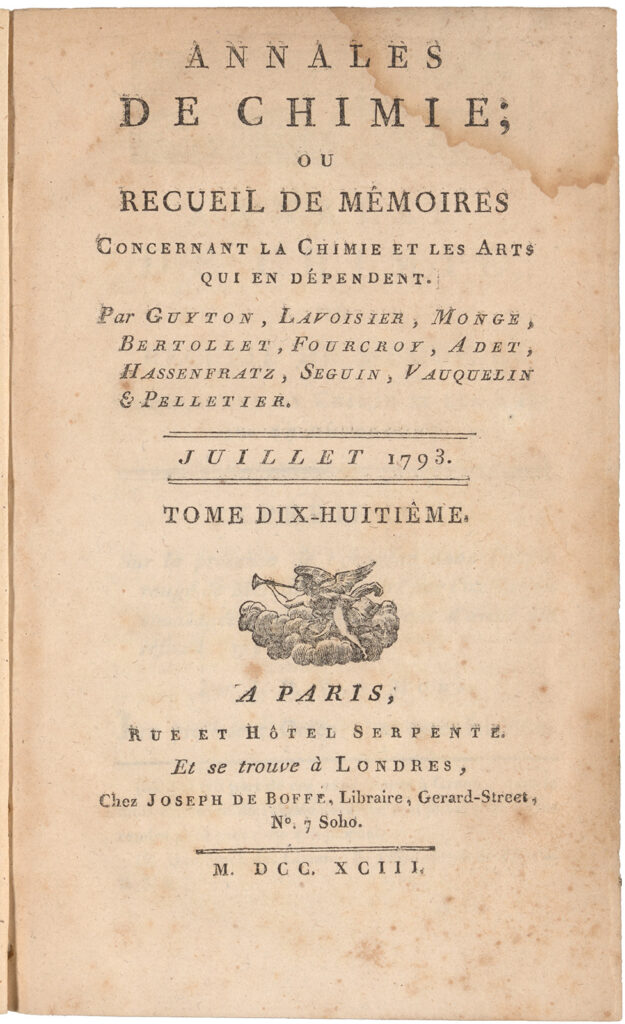

The purchase was brokered by a trusted book dealer because finding a home for the Annales was a delicate proposition. He couldn’t afford to risk owning all 401 volumes himself without a buyer. And libraries have been shedding journals in recent times, not acquiring them. But he knew us and thought a run that went clear back to the founding with Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier himself on the masthead might pique our interest. He was right, and with a strengthening of the dollar against the euro and a little creative budgeting on our end we had a deal.

The skepticism about acquiring a full run of a journal for the rare book collection was shared by some of my fellow librarians at the time, and for my sins I was entrusted with the physical processing of the collection. As I unpacked and inventoried each volume, I began to get a sense of just what it was we had acquired and how even the material artifacts that were passing through my hands told a story.

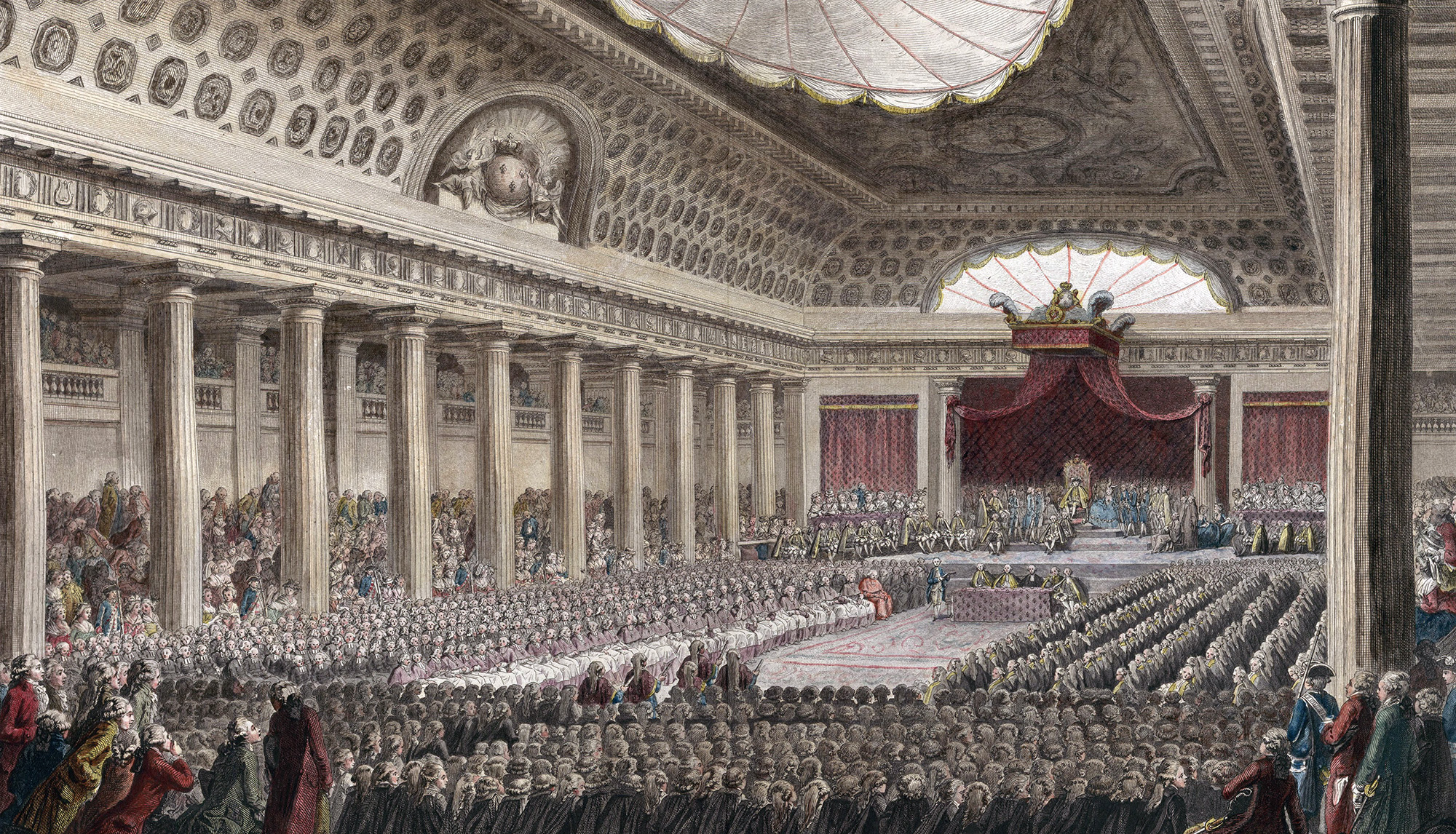

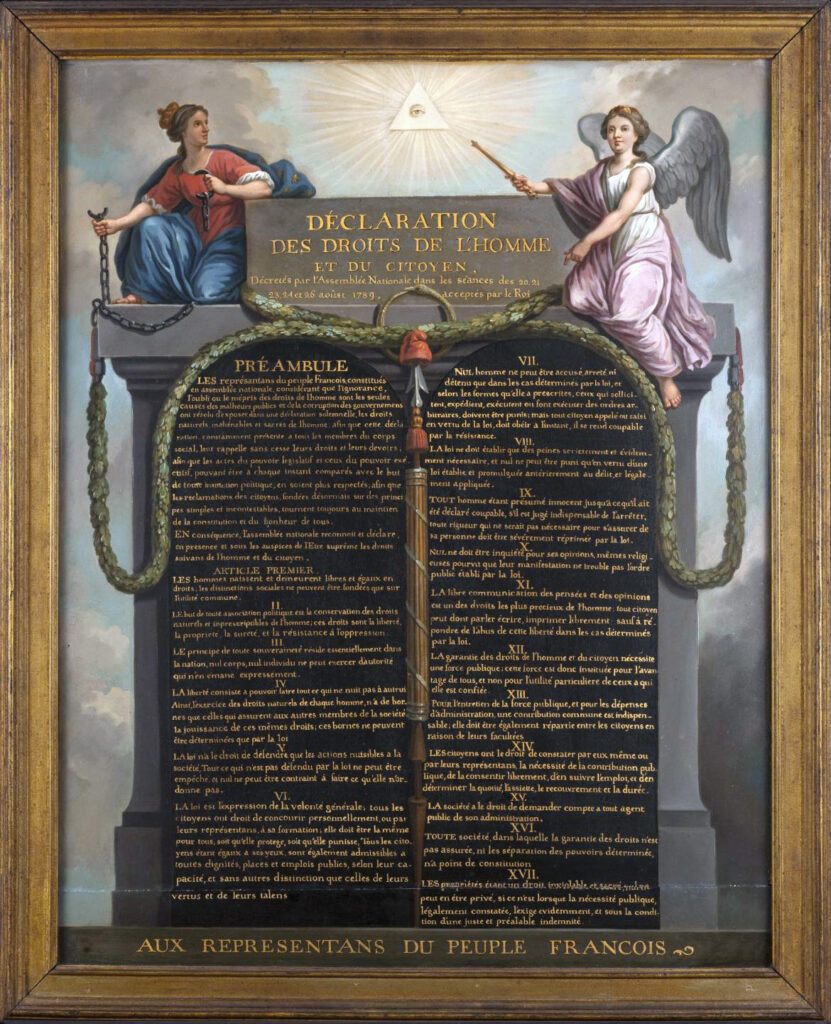

It was mostly in the earliest volumes, still in their original paper publisher’s bindings, that the tale unfolded. The first thing that struck me as I put the volumes in order was the abrupt appearance of the French revolutionary calendar numbering years not from the beginning of the common era but from the glorious establishment of the French Republic on September 21, 1792.

And then, of course, there was the uncomfortable matter of Lavoisier, whom I knew did not survive the revolution. Starting with the masthead, these early volumes of the Annales de chimie tell a story of rapid and terrifying change as the chemists who put it out sought to adapt and survive as France went into convulsions around them.