When the word vitamin was coined in 1911 by a Polish biochemist named Casimir Funk, no vitamin had ever been chemically isolated: in fact there was still some debate among nutritionists about whether vitamins actually existed. But that didn’t prevent food manufacturers and their advertising firms from capitalizing on the appeal of the term. Not only did these mysterious dietary compounds seem to need regular consumption in unknown amounts, but they were also tasteless, invisible, and immeasurable. To marketers these qualities made them irresistible.

“The food manufacturers have discovered a new language,” wrote one nutritional chemist in a 1929 issue of Good Housekeeping. “Old staples that you and I bought because we liked the taste and found them ‘filling’ are now appearing in the advertising pages with new appeals to attention. They’re rich in vitamins! Apparently that statement ought to be enough to make us open our pocket-books and purchase forthwith.”

Vitamin C “cannot be stored in the body longer than 24 hours,” warned one ad for Sunkist lemons. “It is essential that it be replenished daily.” Manufacturers of cod-liver oil, which is a natural source of vitamin D, began referring to it as “bottled sunshine.” They came up with a mint-flavored version and advertised its supposed ability to give babies “well shaped heads.” Iceberg lettuce, which is essentially water in leaf form, became “nature’s concentrated sunshine”; bananas were a “natural vitality food.” Ralston Wheat Cereal put “the B1 in breakfast.” “New research” suggested it was probably a good idea to “start or end one meal a day with canned pineapple.” If you didn’t want to risk vitamin starvation (“a danger that gives no warning!”), you’d better eat Del Monte “vitamin-protected” canned foods. Schlitz Sunshine Vitamin D Beer launched in 1936 with the tagline, “Beer is good for you . . . but Schlitz, the beer with sunshine vitamin D, is extra good for you.”

Marketers weren’t just content with using vitamins to boost the appeal of already popular foods. Once they had used vitamins to establish the concept that foods should be judged not by their taste but by science, the next step was to use vitamins to create a desire for products that had lacked any previous demand at all. My favorite example of this phenomenon is a product that almost no one wants anymore—but which is a great case study in how profoundly vitamins have influenced both current nutritional trends and our overall attitude toward food. I’m talking about yeast cakes.

Yeast cakes? When I first read the term in historian Harvey Levenstein’s Revolution at the Table, I had no idea what it meant. At first I thought it might refer to a precursor to Marmite, the salty yeast spread beloved by the British and reviled by nearly everyone else. Then I found a 1920s ad that referred to yeast cakes as “creamy wholesome candy” and encouraged readers to “try a luscious bite,” which made me think of some sort of confection, like those leaf-shaped cakes of soft maple sugar found at roadside stands in Vermont. Or maybe yeast cakes were a baked good, like a sort of leavened biscuit or a particularly spongy dessert.

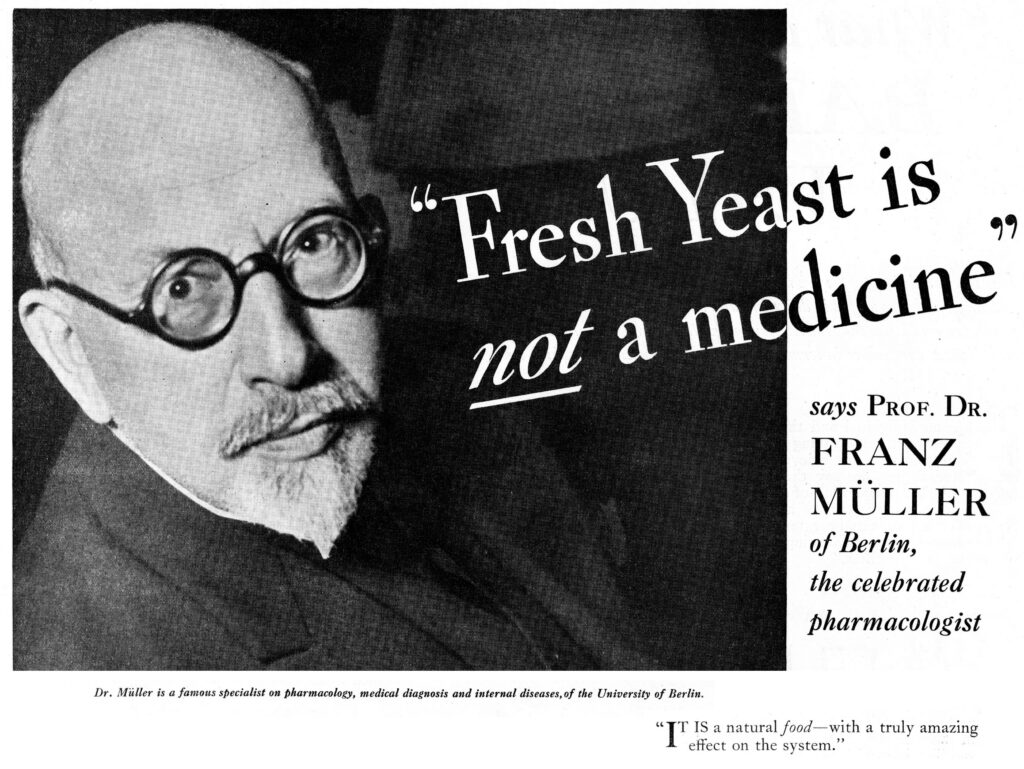

The particular ads that had caught my eye began in late 1928 (though the campaign had started earlier) and featured pictures of stern-looking doctors accompanied by cartoon diagrams of intestinal tracts and the word constipation in surprisingly large type.

“The fastidious, successful women of today know how to avoid the damaging effects of clogged intestines,” said an ad featuring a Dr. Gaston Lyon, supposed laureate of the Academy of Medicine in Paris. Another, starring “the noted Vienna hospital authority” Dr. Januschke, claimed that so-called sluggish intestines were the “cause of more ill health—more actual, permanent sickness—than any other one disease!” The photographs were so stern, the copy so insistent. By the time I read a testimonial from Britain’s Dr. Leonard Williams, who announced to readers in 1929 that “I should like to prescribe less feasting and more yeasting,” my curiosity was thoroughly piqued.

It turns out that, true to their name, yeast cakes are simply yeast that has been pressed into a cake and wrapped in foil like a bouillon cube. Like all yeast, it’s a natural source of many B vitamins. It’s technically the same yeast found in active dry yeast, a fungus called Saccharomyces cerevisiae that feeds on fermentable sugars and releases ethanol and carbon dioxide as waste products. (S. cerevisiae is the yeast used by bakers and brewers; the carbon dioxide causes the dough to rise and the beer to bubble.) But active dry yeast is, well, dry; yeast cakes, which are made from fresh or “compressed” yeast, are not. Their moisture makes them go bad quickly, which is the main reason fresh yeast was mostly supplanted in the 1940s by the less perishable granular powder that’s common today.

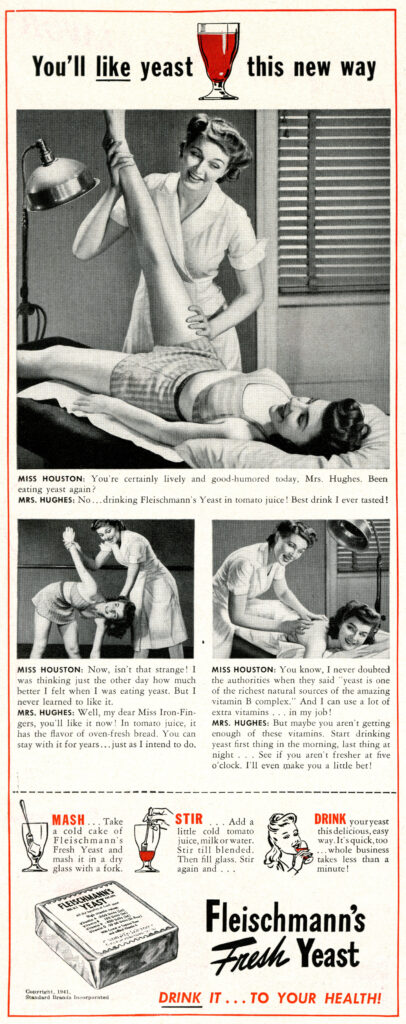

Fresh yeast is still used by commercial bakers, but for most people it’s no longer a household term. In the 1920s and 1930s, however, everyone knew about yeast cakes. They were such a popular, faddish health food that they were available everywhere, from groceries to cafeterias, lunch counters, and soda fountains; whether eating the cakes whole or dissolved in drinks, consumers could get an extra vitamin fix wherever food was sold.

It’s worth pausing here to acknowledge how strange it is this trend caught on, given the actual taste of yeast. The ads said that you could eat your yeast “in the cake or crumbled” in water, fruit juice, or milk. If the idea of yeasty orange juice lacked appeal, the cakes could also be consumed as is. “Yeast,” said the copy of one early ad, “has a pungent, appetizing taste.”

But when I managed to procure a yeast cake of my own (in the dairy section of a New Jersey grocery store), I immediately knew that it wasn’t going down easily. The cake was a grayish beige, with a smooth surface similar to clay. I concur with the ad copy that the smell was pungent, but “appetizing” is not an appropriate word choice. Its odor was sour, as if I’d stuck my head into a vat of stale beer. What really dampened my enthusiasm, though, was the texture. When I took a bite, it snapped in a crisp yet muted way and immediately began to dissolve. It coated my tongue and the roof of my mouth and became tacky, as if I had eaten a spoonful of paste.

“I don’t think I can do this,” I said to my husband, thinking of the millions of live, active fungi that were now stuck to my teeth. I tried to put the rest of the cake in my mouth but my hand refused to lift it to my lips. Ignoring the advice from 1925 (“yeast is especially delicious on toasted crackers or as a sandwich ‘filler’ with jam or peanut butter”), I placed the rest of the cube back in the refrigerator with its four companions.

In a last-ditch effort I brought several cakes to my in-laws’ for Thanksgiving to see if other people might find them more appealing. And indeed, when I mentioned the cakes to my husband’s 91-year-old grandmother, her face lit up. “Ooh, I love yeast cakes!” she said, before taking a nibble. “The texture is so nice.” Encouraged, I then spent the weekend trying to press yeast cakes on her. Eventually she turned to me. “You know, Catherine,” she said, “sometimes people say things they don’t entirely mean.”

‘I don’t think I can do this,’ I said to my husband, thinking of the millions of live, active fungi that were now stuck to my teeth.

So how did this trend begin? After all, no one was munching on raw yeast in the 1860s, when the rise of yeast cakes begins. At the time, America had no commercial yeast business to speak of. Instead, American home bakers used yeast derived from a variety of sources, including wild yeast collected from the air, yeast from “starters” passed on between bakers, and foamy brewer’s yeast skimmed from the top of fermenting beer. Each of these strains of yeast had different tastes and leavening effects, making it difficult to ensure that the yeast used for one batch of bread would taste or rise like another.

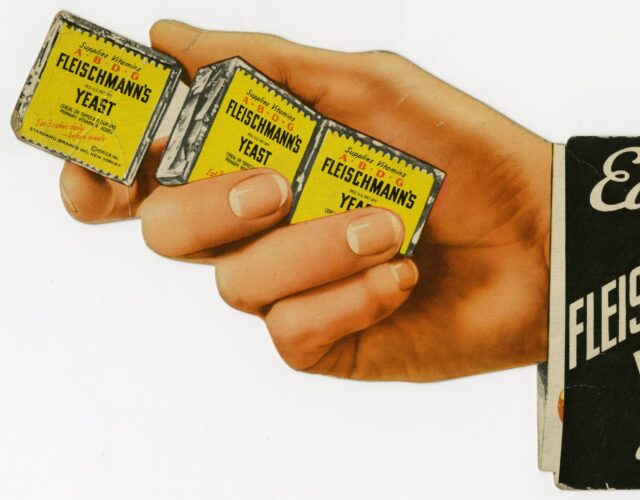

Sensing an opportunity, Charles Fleischmann—a recent immigrant who had been trained in distillation and yeast production in Europe—teamed up with a businessman named James Gaff and began mass-producing yeast in a distillery near Cincinnati. Once the yeast had eaten the starter (multiplying millions of times in the process), the yeast was rinsed and pressed into cakes. The cakes were wrapped in tin foil and sold as quickly as possible, often door-to-door and originally by Fleischmann himself. Since one of the by-products from yeast production is grain alcohol, Fleischmann and Gaff also founded the Fleischmann Distilling Company and were soon producing gin.

The ensuing decades saw great business as the popularity of home baking exploded and refrigerated railway cars made it possible to quickly distribute fresh yeast throughout the country. But by 1920 Fleischmann’s market had suffered two serious blows: the availability of store-bought bread, which led to a decline in home baking, and Prohibition, which immediately destroyed half of the company’s business. A history put together by one of Fleischmann’s advertising companies summed up the situation: “The Fleischmann Company realized that they would have to develop a new material for their product, a new want for yeast.”

The company turned to a professor of physiological chemistry at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and asked him to study the health value of baker’s yeast. The professor complied and published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association. “The Use of Bakers’ Yeast in Diseases of the Skin and of the Gastro-intestinal Tract” concluded that yeast eating had been proven to cure boils, acne, and various skin and stomach issues. The Fleischmann Company reprinted this study in a booklet and did a mass mailing to doctors across the United States. To drive the point home the company also took out ads in several medical journals and offered to send out free copies of a booklet called Yeast Therapy.

Between three and four million copies of the booklet were distributed through grocers between 1918 and 1919, but sales of yeast still were not what the company had hoped for. So Fleischmann’s hired an advertising firm that proposed to boost yeast’s sales by linking it to a hot new trend that had just begun to capture the attention of the public: vitamins. The first ad in what is now known as Fleischmann’s Yeast for Health campaign appeared in 1920 with a picture of an attractive young woman dropping a cake of yeast into a glass of water above copy claiming that yeast “has been found to be rich in Vitamins, an element the body urgently requires.”

This first campaign was based on truth: as noted, yeast naturally contains B vitamins, which at that point were thought to be a single substance. It also really does act as a laxative. But when in 1920 Fleischmann hired a new advertising firm, the J. Walter Thompson Company, to expand on the idea of “yeast for health,” the company’s claims began to multiply almost as quickly as the yeast spores themselves. Now, in addition to being a curative for constipation, yeast was good for skin troubles, stomach troubles, and a “general run-down condition.” Eat a cake before every meal—but be patient: results, the ads emphasized, might take months to see.

The ensuing campaign was so popular that when the Thompson Company launched a contest in the summer of 1923 that offered $5,000 in total prizes for people’s positive testimonials about yeast cakes, they received 8,340 responses. “I am a mail-carrier, and it may sound strange that a man walking twelve miles a day, six days a week, should suffer from constipation,” said one example that ran in McCall’s Magazine in March 1924. “After the first month [of yeast eating] I noticed a remarkable difference, and when Saturday night came, I still had some pep left. . . . Fleischmann’s Yeast has relieved me completely of constipation and I feel tip-top all the time.”

For the first round of personal testimonials, the company had been using photographs of models to illustrate the advertisements. Then, starting in 1925, Thompson’s copywriters and photographers began tracking down the actual letter writers themselves. The firm later claimed that this made the campaign “absolutely accurate in every detail,” but a 1926 article for the company newsletter—“How We Get Yeast for Health Photographs, Written by One Who Has Taken Many of Them”—suggested otherwise.

The article, which is really more of a confessional, was penned by a photographer I wish I could have met. “We rang doorbells all over the city,” he wrote, after listing the “ingredients” necessary for a good shot, including “ingenuity, tact, eloquence, endurance.” The assignment proved challenging, despite the 5,000 testimonials to choose from. “Many of our Yeast eaters had moved; some were sick in bed; some were deaf; too old; too young; too fat; too hopelessly ugly,” he claimed. But that didn’t stop his intrepid team. On a portrait of a little boy he remarked,

On a woman with a “heavy face but a divine figure,” the photographer recalled,

The campaign was enormously successful: Fleischmann’s Yeast sales tripled between 1917 and 1924. Between 1924 and 1925 the company’s net income was up an additional 75%, and by 1927 Fleischmann’s sales of yeast in the United States was 2.45 pounds per capita. As the J. Walter Thompson Company put it in an internal report, “The effect of the ‘Yeast for health’ campaign in increasing sales of Fleischmann’s Yeast is very clearly shown.”

This was a truly amazing achievement, a triumph in advertising and a tribute to the almost hypnotizing power of vitamins. Yeast cakes are also emblematic of one of the more peculiar aspects of our modern relationship with nutrition: with the right health claims affixed to them, foods are no longer required to taste good.

Despite the actual taste of yeast, by 1928 the Yeast for Health campaign had helped Fleischmann’s capture 93.4% of the yeast business in the country. That’s when the company decided to launch the foreign doctor campaign mentioned earlier, in the hope that stern physicians talking about bowels would appeal to the small segment of the public unmoved by the Yeast for Health campaign.

As more vitamins were discovered and new technologies developed, yeast also lent itself nicely to vitamin fortification. In late 1929 Fleischmann’s began irradiating its yeast to create vitamin D to fight against what ads called a “sun-starved” race—“soft-boned, weak-muscled, teeth a prey to decay.” Once vitamin B was divided into thiamin (B1) and riboflavin (B2, then known as vitamin G), the ads were able to claim that Fleischmann’s yeast was “rich in three vitamins.” Then in 1934 a new strain of yeast was introduced (“XR” yeast—“that’s the scientists’ name for it”) that contained vitamin A. According to the ad copy, this meant the yeast could reduce your risk of getting a cold. But don’t worry, a parenthetical reassured, XR yeast was “as good as ever for baking.”

By the mid-1930s yeast’s four vitamins and unspecified “minerals and hormone-like substances” had emboldened its advertisers to the point where they actually began to argue that yeast was better for health than straight-up fruits and vegetables. An ad in 1935 claimed that Fleischmann’s Yeast “supplies ‘Protective Substances’ your stomach, bowels need to work properly,” and that “no other food, even fruits and vegetables, gives you enough of them!”

Eventually the ads were too much. The Federal Trade Commission filed a cease-and-desist letter against Fleischmann’s parent company, Standard Brands, in 1931, protesting what it claimed were misleading ads; seven years and many claims later, the commission finally succeeded, and Fleischmann’s was forced to scale back its assertions. By then health claims included the prevention of tooth decay; the strengthening of intestinal muscles; the prevention of pimples, “furry tongue,” and colds; a cure for “fallen stomach”; improvements to breath; a cure for depression; a reduction in headaches and fatigue; an increase in “pep”; the elimination of crying spells; help for digestion; an increase in skin’s “self-disinfecting power”; the sharpening of intellect; and the prevention of obesity. One ad from 1937 included a testimonial claiming that Fleischmann’s Yeast, whose abilities apparently now rivaled those of Jesus, had restored a woman’s ability to walk.

Today the idea of mandatory pre-meal yeast cakes sounds both disgusting and preposterous: who would ever believe that such a specific and isolated ingredient would be the secret to vitality? I recently asked myself that question as I strolled the grounds of Natural Products Expo West, the largest trade show in the United States for the country’s natural and organic food industry. Within minutes I had been offered samples of hemp-infused drinks, chia-seed puddings, and ancient-whole-grain brownie bites—products that promised improvements to my health if consumed in sufficient quantities. Oddly textured and not that tasty, these creations seemed like perfect representations of just how far we’ve come since the public’s introduction to vitamins in the 1920s and 1930s—the heyday of yeast cakes. By which I mean we haven’t come very far at all.

This article is adapted from Vitamania: Our Obsessive Quest for Nutritional Perfection. Read our review of Vitamania.