In the fall of 1918, the (misnomered) Spanish flu ravaged much of the world. Philadelphia was hit especially hard: it had the highest death rate of any major American city. Over the course of six weeks, 12,000 people in the city died. Hospitals were overcrowded, and bodies piled up.

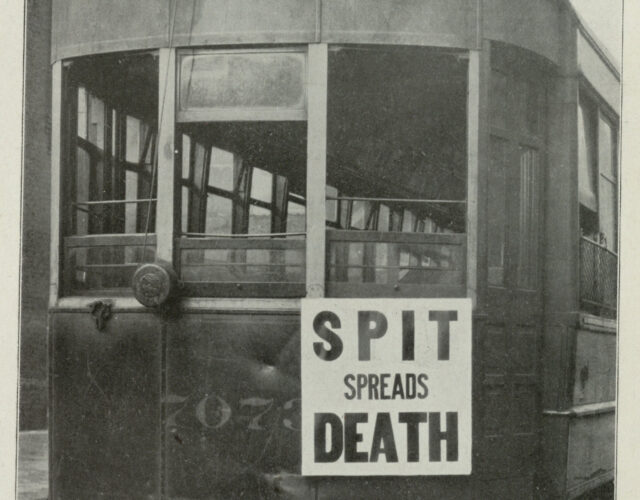

When the Mütter Museum embarked on the multiyear exhibition and public art project Spit Spreads Death, the curators and researchers behind it had no idea how relevant it would become—or how quickly.

Credits

Host: Alexis Pedrick

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Music: “Dry Earth” by Robbie Redway and Ben Jackson, courtesy of the Audio Network. “Titter Snowbird” and “Lunette Interlude” by Blue Dot Sessions.

Audio Excerpts: From Spit Spreads Death: The Parade, a flim by Blast Theory with music by David Lang, performed by The Crossing, © 2019 Blast Theory, all rights reserved.

Research Notes

Davis, Kenneth C. “Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu.” Smithsonian Magazine, September 21, 2018.

Flynn, Megan. “What Happens If Parades Aren’t Canceled during Pandemics? Philadelphia Found Out in 1918, with Disastrous Results.” Washington Post, March 12, 2020.

Mütter Museum, College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Spit Spreads Death: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–19 in Philadelphia. Exhibition, 2019–ongoing.

For further reading check out:

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Penguin RandomHouse, 2005.

Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Porter, Katherine Anne. Pale Horse, Pale Rider. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1990.

Spinney, Laura. Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. PublicAffairs Books, 2017.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to Distillations. I’m Alexis Pedrick. Our team is busy working on our upcoming season, even as we self-isolate, but we had a hunch that a lot of you could use something new to listen to now. So this is the first of several short interviews that’ll be appearing in your feed. Some are going to be relevant to what we’re living through right now, and some are going to be completely unrelated, random history of science nerddom or bonus content from our upcoming season.

Alexis: Today we’re talking to Jane Boyd, the historical curator for a multiyear project at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. It’s called Spit Spreads Death, and it’s about how the influence of the pandemic of 1918 hit the city of Philadelphia. And it’s more than just a static exhibit in a museum; it also incorporates public art projects and community health programming.

The show opened in September, and while of course you can’t go see it now, it’ll be open until 2024, so you have plenty of time. We talked to Jane about the eerie parallels between the 1918 pandemic and our current global health crisis.

So I’m just going to start at the beginning. Can you give us a snapshot of what Spit Spreads Death is all about?

Jane: So what we wanted to do was use Philadelphia’s experience in this global pandemic, which killed 50 to 100 million people worldwide, and see, use that to explore how communities respond to these severe public health crises.

So it really talks about how this pandemic blazed through the city in a matter of weeks, for the worst part of it. And it affected every block and every family, and it left a lot of questions behind it that are still unanswered even after 100 years, like, How many people died in this pandemic?

We’re never going to know that exact number, partly because in places like Africa and India that didn’t have a lot of people recording all this information at the time, we’re not necessarily going to know what those figures are. Other questions are what exactly caused the pandemic, this particular pandemic virus, this variant of influenza, to be so very deadly?

That’s a question that is still being figured out. Why did it kill so many young people? Most infectious diseases kill the very young babies and children and the very old, but this disease hit very heavily among people in the prime of their life, people in their 20s and 30s. So those are the kinds of questions that are being asked in terms of how many people actually died in Philadelphia.

We had some numbers that the city had compiled at the time, but what we decided to do was to go back into the death certificates and transcribe the death certificates to figure out who died, where they lived, how we could map the progress of the disease through the city. This was something that visitors told us they were interested in seeing.

So we embarked on this grand data-gathering project and analyzed all of these death figures, and came up with a figure of about 17,500 people died of influenza and related infections over the six months of the pandemic. And 14,000 of those died within six weeks, making one death every five minutes.

So using, gathering all that data—which we’re going to put that dataset online for future researchers to use—that enabled us to create digital interactives that actually show all the deaths in the city. They pop up as red dots, and you can search for a family name. You can search for a street.

You can find out if someone died in your house or near a landmark that you were interested in, and find out how the pandemic affected particular neighborhoods. And those names also allowed us to, for marchers in the memorial parade, to choose someone to hold, hold that person’s name as a sign and to represent that person in the parade.

Alexis: The Mütter Museum worked with a U.K. artists group called Blast Theory to create a public art project based on the flu pandemic.

Jane: They decided to do a parade as an echo of the Liberty Loan wartime fundraising parade in 1918 that was one of the triggers for the rapid spread of the influenza pandemic virus in Philadelphia.

Alexis: On September 28, 1918, Philadelphia hosted its largest parade ever—the Liberty Loan parade. Two hundred thousand people crowded together on Broad Street to celebrate war bonds and support the war effort. But just days earlier, a mysterious and deadly influenza had arrived in the city, and city leaders knew about it, but they allowed the parade to go on. Within three days every bed in the city’s 31 hospitals was filled.

Jane: So I’ll talk a little bit about the parade that was done by the artist group Blast Theory in order to convey some of the sort of personal and emotional dimensions of this pandemic that hit Philadelphia particularly hard. Philadelphia was the city in the U.S. that had the highest death rate among the top largest American cities. So this parade was meant to be a memorial for the victims but also a celebration of the public health workers that keep us all safe today.

Alexis: The Blast Theory parade happened on September 28, 2019, 101 years to the day after the Liberty Loan parade, and anyone was welcome to participate. Many Philadelphians came out to honor family members who had died or gotten sick during the 1918 pandemic. Health-care workers marched in scrubs. And people honored victims by holding signs with their names on them.

The following excerpts are from the artists’ film of the event made by Blast Theory:

>> Calls from crowd >>

Male voice: The amount of people that showed up here, it was a testament to how many people were touched by this epidemic.

Female voice: My grandparents were very sick, so I think a lot of people I’ve met have memories.

Alexis: I was reading a blog post where the museum director, Robert Hicks, wrote that he anticipated that visitors coming to the Mütter Museum during the lifetime of the exhibition would immediately make a connection to recent news reports of certain killer disease outbreaks somewhere in the world. But could any of you have imagined how close to home this would all become, and sort of how quickly?

Jane: Well, certainly not. I mean, we knew, as Robert said, that since disease outbreaks are frequent all over the world, that something would happen over the course of the run of this exhibition that people could make connections to in the news. And for instance, when we were planning the project, the Zika virus was in the news.

That seems a million years ago.

Alexis: No, gosh, you’re right. It is. It’s so true. Oh!

Jane: But fortunately, severe pandemics are much more rare than those kinds of outbreaks. For influenza there’s only been three pandemics since 1918: in 1957, in 1968 to 1969, and in 2009, the swine flu pandemic, which many people remember.

So it’s the sort of thing where something is going to come down the pike. You just don’t necessarily know what or when it’s going to be. So we knew it would be relevant. We absolutely did not anticipate that it would become this extremely relevant so extremely quickly, just a few months after the exhibit opened.

So we had our parade, our parade with 400 marchers at the end of September. We can’t, that’s unimaginable now to have something like that.

Alexis: Right. No, absolutely. I mean, I think it’s really interesting to sort of think about the parallels between what’s happening in the world right now and what was happening back then in 1918. Are there parallels that you see in terms of what we’re living through now?

It seems like Philadelphia’s response is very different today than it was in 1918.

Jane: No. Certainly that is true. And I think that experience of 1918 has, it’s most likely informing the very cautious response today. But to go back to the past, that pandemic killed more people more quickly than any other disease then or since. There have been plagues and pandemics that have killed, certainly killed more people but not as quickly.

And the spread of the pandemic virus was exacerbated by this movement of people during World War I, you know, thousands, millions of people moving over oceans and borders and continents. And this, it also happened at the very end of the war. And at the time there were no vaccines, no antibiotics to use against pneumonia, which was the most common secondary infection.

That was the real killer. Influenza would weaken your immune system, and then the pneumonia would come in and really carry you off. And even though we know a lot more medically and scientifically than we did then, you know, we know how viruses work. They didn’t know that influenza was a virus at the time.

They had identified a bacterium as the disease-causing agent. And they developed some vaccines against that, but that was mistaken. So today we know how viruses work. We can analyze their genomes; we can use that to develop vaccines against them. And so we have much more advanced medical and scientific knowledge, and our treatments are much more advanced.

But with coronavirus, with this novel virus that’s very virulent, we can really be sort of, it’s like a time-travel machine. It just takes us right back into 1918 conditions because it takes time to develop and test a virus. In the meantime these hospitals and doctors and nurses get overwhelmed. Supplies and equipment run short.

The coffins start to stack up because they, people are dying more quickly than they can be buried. Temporary hospitals get set up in auditoriums and parking lots. The stories and photos that I’m seeing from places like Bergamo, Italy, and now from New York, just very close to us here in Philadelphia, there are lots and lots of echoes of 1918. So even with all this medical and scientific knowledge that we have, when systems reach their breaking point, we’re really living those past conditions all over again in some ways.

I would say that if there was one lesson to draw from 100 years ago, I would say that it’s the importance of transparency. And it wasn’t possible at the time to be transparent about the situation.

There were federal laws that mandated press censorship and punished free speech, all to keep up wartime morale. But people in power really need to be honest about the situation. They need to say what is happening, what’s being done, and issue very clear guidance about what individuals should and shouldn’t do.

And we’ve seen what goes wrong and how many people suffer when that transparency is lacking, both 100 years ago and today.

Alexis: As we’re thinking about 1918, you know, today, are we ever really going to be the same? You know, are we forever changed? Are we always going to sort of obsess over these germs and, you know, be scared of embracing our friends and, you know, all of that sort of stuff? And so I think, you know, I wonder after 1918 were Philadelphians really forever changed?

Jane: Well, the pandemic came and went very quickly, and it’s looking like our experience is going to be a bit more long and drawn out, even if the actual peak of the disease in any particular location is going to be really quickly. But in 1918 the worst weeks in Philadelphia were from late September to early November, and the peak was in October—in 1918.

But very soon after the death rate dropped, the end of World War I was declared. So there was enormous relief and rejoicing on November 11, on Armistice Day and afterward. That terrible toll of the pandemic was kind of swept under the rug to some extent, and many people just wanted to forget about both of those traumas—the pandemic and the war.

So they really didn’t talk about their experiences and their feelings. An additional thing is, since there wasn’t a public memorial for the victims of the pandemic, and there are only very few pandemic memorials anywhere in the world, there really wasn’t any sort of communal way for people to grieve those losses.

So because diseases have not been viewed as the same kind of historic event as a war or some other kind of political conflict, they just are treated as kind of the ebb and flow of life. And so it’s something that just gets remembered privately and not in a communal fashion, even though these deaths came out of an event that affected the entire world.

There just wasn’t that kind of recognition that this was something that was worthy of commemoration in that way, unlike the combat losses of the soldiers and sailors. Those do have memorials. And people really mostly mourned really quietly and very privately. And I think that’s part of the reason why this pandemic used to be called the “forgotten pandemic.”

That’s because historians didn’t really pay much attention to it until later in the century. Most histories of that time were focused on political events and military events, but we found in our research that people definitely remembered the pandemic, not just those loved ones they lost, but also those emotions and sensations and sights and sounds and even the smells of living through those terrible weeks in those terrible months.

For instance, there are oral histories recorded from Philadelphians in the early 1980s, where people talk about seeing coffins stacked up and smelling the dead bodies and being just afraid. And when people started to hear about this project, our project, they began to send us stories of the pandemic that were passed down in their families. And we have dozens of these stories so far and more coming in every day, and we were able to put some of the stories into the exhibition. And we’re compiling more of them to make a digital scrapbook to go online later this year.

Alexis: Wow. That is amazing. That was actually going to be my next question. I was going to be, like, has anyone actually sent you anything so …

Jane: Absolutely. So actually I can tell you a really incredible story that we got at the beginning of the year.

Alexis: Yeah, please.

Jane: So this is a story a woman sent in that her mother used to tell.

So when the mother was a baby, her family lived in Camden, New Jersey, across the river from Philadelphia. There was a twin sister who died in the pandemic, but there wasn’t any undertaker available to bury the body. So the mother was absolutely desperate. So she put the dead baby and the living baby into the carriage and took them on the ferry across the river to Philadelphia. And this was before the Benjamin Franklin Bridge was built.

Because she knew an undertaker in her old neighborhood, in Frankford, a neighborhood in Philadelphia… So this is one of the harrowing parts, is that people on the ferry were complimenting her on her beautiful children, and all the while she was just terrified that she’d get caught for transporting a dead body across state lines.

Alexis: Oh my gosh.

Jane: Isn’t that amazing? So when she got off the ferry, she walked several miles north to Frankford, pushing the baby carriage to reach the undertaker, where she left the body. And the woman who wrote this letter telling us this said that the story was told regularly at family gatherings.

And you start to wonder, what was it like to grow up with a kind of origin story like that? Totally sort of haunted by your dead twin and by this trauma of your mother.

Alexis: Yeah.

Jane: So we have lots of stories like that, but not as dramatic as that one. But they really show how deeply the pandemic affected people.

So really people were changed because of their intense experiences. And they did carry their memories with them, even if they didn’t really talk about them at the time. So if people have family stories, we’d like you to send them to influenza1918@collegeofphysicians.org, or visit the Mütter Museum website for the address, particularly from the Philadelphia area.

We’re also interested in finding out if you have an artifact passed down in your family from someone who died in the pandemic, or photographs or documents. We’d really be interested in hearing about those.

Alexis: Thank you so, so much, Jane. Really, this was fantastic.

Jane: Thank you. You too. Bye-bye.

Alexis: Thanks to Blast Theory for letting us use excerpts from Spit Spreads Death: The Parade, a film by Blast Theory, with music by David Lang performed by the Crossing. For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Thanks for listening.