Almost six million people in the United States have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. And with baby boomers getting older, those numbers are only expected to rise. This disease, despite being studied by scientists for more than 100 years, has no cure. In our two-part series, we first dive into the personal lives of the people at the heart of this disease: the patients and their caregivers. Then we uncover why effective treatments for Alzheimer’s lag so far behind those for cancer, heart disease, and HIV. It turns out that for all the decades researchers have been at war with the disease, they’ve also been at war with each other.

Credits

Host: Alexis Pedrick

Reporter: Rigoberto Hernandez

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: James Morrison

Music courtesy of the Audio Network, the Free Music Archive.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions: “Kalsted,” “Stretch of Lonely,” “Thin Passage,” “Waltz and Fury,” “Dash and Slope,” “Gilroy Solo,” “House of Grendel,” “Uncertain Ground,” “Watercool Quiet.”

Research Notes

“2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures.” Alzheimer’s Association, 2019.

Begley, Sharon. “As Alzheimer’s Drug Developers Give Up on Today’s Patients, Where Is the Outrage?” Stat News. August 15, 2018.

Begley, Sharon. “The Maddening Saga of How an Alzheimer’s ‘Cabal’ Thwarted Progress toward a Cure for Decades.” Stat News. June 25, 2019.

“Biogen Alzheimer’s Drug Shows Positive Results.” CNBC. July 25, 2018.

“The Clinical Trial Journey.” Mayo Clinic. Youtube video. June 5, 2019.

Garde, Damian. “Alzheimer’s Study Sparks a New Round of Debate over the Amyloid Hypothesis.” Stat News. July 30, 2018.

Hogan, Alex. “The Disappointing History of Alzheimer’s Research.” Stat News. May 21, 2019.

Itzhaki, Ruth. “Alzheimer’s Disease: Mounting Evidence That Herpes Virus Is a Cause.” The Conversation. October 19, 2018.

Keshavan, Meghana. “On Alzheimer’s, Scientists Head Back to the Drawing Board—and Once-Shunned Ideas Get an Audience.” Stat News. July 22, 2019.

Li, Yun. “Biogen Posts It’s the Worst Day in 14 Years after Ending Trial for Blockbuster Alzheimer’s Drug.” CNBC. March 21, 2019.

“Lilly Alzheimer’s Drug Does Not Slow Memory Loss: Study.” CNBC. November 23, 2016.

“The MacNeil/Lehrer Report; Living with Alzheimer’s.” 1983-04-12, National Records and Archives Administration, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and the Library of Congress), Boston and Washington, DC, accessed October 16, 2019.

“The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour,” 1991-08-16, NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed October 22, 2019.

Makin, Simon. “The Amyloid Hypothesis on Trial.” Nature. July 25, 2018.

Prusiner, Stanley. Madness and Memory: The Discovery of Prions—A New Biological Principle of Disease. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Robakis, Nikolaos, et al. “Alzheimer’s Disease: A Re-examination of the Amyloid Hypothesis.” ALZforum.org. March 26, 1998.

Shenk, David. “The Forgetting—Alzheimer’s: Portrait of an Epidemic.” New York: Anchor, 2013.

“Virginia Lee and John Trojanowski on the Protein Road Map to Alzheimer’s.” Science Watch. December 2011.

Transcript

Part One

Evan: I don’t necessarily have faith in a higher purpose, but I believe in my responsibility to take care of my parents, and that is easier than deciding what my own responsibilities are towards myself, for my own sake. There’s a lot more moral clarity in taking care of someone else.

Rigo Hernandez: My name is Rigoberto Hernandez, I am one of the Distillations producers. A couple years ago, my friend Evan moved back to Boston to take care of her mom, Lanng. For years, Evan noticed that her mom was having problems with her memory, and then she started putting off major tasks. Evan is 30 years old and Lanng is 72, but Evan filed the paperwork for her mom’s divorce and sold their house. Now she handles all of Lanng’s finances.

Lanng Tamura: I mean in some ways she functions like a parent, you know? That’s how I view it.

Rigo Hernandez: How does that feel?

Lanng Tamura: Well, that’s a good question because I think part of me feels bad about it that she’s so young because she’s busy. It’s not like she doesn’t have anything to do. She’s got a full-fledged career, so it sort of bothers me at a practical level.

Rigo Hernandez: Soon after Evan moved in, Lanng was diagnosed with something called mild cognitive impairment, which basically means that someone’s memory, language, thinking, and judgment has started to slip. It’s a diagnosis that puts her somewhere between normal aging and full-fledged dementia, but where exactly that is on the spectrum is hard to say. Some people with mild cognitive impairment will get Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia. Others never get worse, and some actually get better. I went to visit Lanng and Evan at the apartment they now share. We started talking about the difference between normal memory lapses and the ones that Lanng is having.

Lanng Tamura:When you get older, your ability to remember stuff, it actually improves, but it’s stuff that happened a long time ago. Your long-term memory actually gets quite stable. It’s short-term memory that falls apart.

Rigo Hernandez: Evan doesn’t agree. She feels that what has been going on with her mother is not normal and doesn’t seem mild. She’s worried that her mother is one of the people who will get Alzheimer’s.

Evan: So maybe in normal aging, that’s how it works for normal aging.

Lanng Tamura: Yeah.

Evan: But in your case, or in the case of someone with a progressive memory disorder, it is actually common to see some changes in long-term memory too.

Lanng Tamura: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah.

Evan: So there are a lot of people that you no longer remember that you used to be pretty good friends with or big events that you don’t remember anymore.

Lanng Tamura: Like what?

Evan: Well, we ran into your friends Mishy and Chris on the bus a little while ago and …

Lanng Tamura: Oh, right.

Evan: … you didn’t know who they were at all, and you didn’t remember when I told you who they were. You didn’t remember ever having known them. It wasn’t like, “Oh yeah. Oh yeah, I can’t believe I didn’t recognize her or I didn’t remember that.” You still don’t know who they were. You don’t remember them or …

Lanng Tamura: Well, it’s not like they were really good friends of mine. They were Grady’s friends and …

Rigo Hernandez: Lanng is clearly irritated. It seems like she feels called out and embarrassed. Evan keeps going.

Evan: Something that came up not too long ago was that I was mentioning Sarah, my ex-girlfriend …

Lanng Tamura: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Evan: … and you said you didn’t remember who that was, and I told you some more detail about her to try to help you remember and you didn’t remember. I said, “Well …” and you said, “Well, I must not have met her.” And you actually had met her a lot and you met her family. The first time I realized you didn’t remember that was actually five years ago and that’s when I first asked you to go see a neurologist with me because I was concerned that you forgot someone who was really important in my life. Also, you didn’t remember experiences that were important to me like moving into my first apartment and how you helped me drive my things down to a new city and get set up. I was really sad that you didn’t remember that.

Lanng Tamura: It’s funny because I don’t remember you talking a lot about that sort of stuff in any case [cross-talk] you talked about it a little bit, but it was more like mentioning it as a fact rather than something that was emotionally charged. Yeah.

Evan: It felt like a big moment in my life, and I wasn’t mad at you for not remembering it. I was just sad because that was something I shared with you when it happened. I was sad that you couldn’t share it with me anymore because you didn’t remember it, and I was concerned. I was concerned about what it meant about your memory. Short-term memory definitely affects you more every day. Right? If you go to the grocery store and you can’t remember what you went there to get, or you go to the grocery store and you buy something and you realize you went this morning and bought it already, that sort of thing.

Evan: … but long-term memory stuff, those are the things that make me sadder …

Lanng Tamura: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Evan: … when you lose those types of things because those are the things that are most important to our relationship.

Lanng Tamura: Okay.

Rigo Hernandez: What Lanng is going through is typical of the early stages of Alzheimer’s. In later stages, anxiety will come out of nowhere, conversations will be interrupted by the loss of names and places. It wouldn’t just be things like for getting what groceries to buy from the store, but forgetting what groceries actually are. Lanng will become more and more reliant on Evan for basic things like showering or going to the bathroom. This is what happens with Alzheimer’s. You lose yourself in slow motion in front of your loved ones.

Alexis Pedrick: Hello and welcome to Distillations. I’m Alexis Pedrick and this is Part One of a two-part series on Alzheimer’s disease. We wanted to bring you this story because today there are almost 6 million people in the U.S. who’ve been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Not only that, there are another 16 million that are caregivers like Evan. As baby boomers continue to age, those numbers are only going to go up. We also wanted to bring you this story because like for so many people out there, maybe even some of you, it’s personal. So for this story, you’re going to hear from me and you’re going to hear from one of our producers, Rigo Hernandez, who did the reporting, including talking to his good friend Evan and her mother.

In this first part, we’re going to focus on the lives of the people at the heart of it, the patients and their caregivers. In Part Two, we’re going to tell you about the science behind Alzheimer’s. It’s a different kind of story with different kinds of stakes. Scientists have been at war with the disease for decades, but despite great hopes, they’re losing because it turns out they’re also at war with each other.

If the two parts of this story feel disconnected, it’s because they are. The people living with Alzheimer’s and those taking care of them don’t often stop and think about the scientific research that’s going on behind the scenes. It’s not a part of their daily lives, and I know because I was one of those people.

My father had something called vascular dementia. It’s not Alzheimer’s, which we’ll explain, but the experience of being someone’s caregiver is similar. In fact, it’s so similar that when Rigo started talking about his friend Evan’s experience, I actually got emotional. Her struggles to make sense of the diagnosis, the strange and overwhelming responsibility of caring for a parent, the dismantling of that parent’s life and the reordering of your own, all while they are—to use a word that doesn’t feel big enough—forgetting. I recognized all of it.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter One—Finding Out Your Parent Has Alzheimer’s.

Alexis Pedrick: To start things off, Rigo’s going to clear up some terms for us, specifically Alzheimer’s versus dementia.

Rigo Hernandez: One of the most common mistakes people make, if not the most common mistake, is that they think dementia is the same thing as Alzheimer’s and it’s not. Dementia is an umbrella term that includes different types of memory diseases. There are lots of dementias that are not Alzheimer’s, but Alzheimer’s makes up about 60% to 80% of all dementias. So to sum it up, not all dementias are Alzheimer’s, but all Alzheimer’s are dementias.

Alexis Pedrick: Exactly. Like I said, my father, Alex, had something called vascular dementia, which is caused by a block of blood flow to the brain. Sometimes this block is caused by a stroke, and that’s what happened to my dad.

Rigo Hernandez: When did you first notice something was wrong?

Alexis Pedrick: I think it started earlier than we realized. I think we were caretakers and didn’t even know we were caretakers in a way, but my mom had breast cancer and at that point in time, she was in stage-four breast cancer. It had metastasized to her bones, and so we were so, I think, kind of overwhelmed with that. We just didn’t have the bandwidth to pay a lot of attention to sort of what was going on with him. We would see it, we would sort of chat with each other and say like, “Oh, did you see this with dad? That seems weird.” And it would go on the list of things we had to get back to.

After my mom died and we had a little bit more bandwidth, we did take him to his doctor. We were concerned because I would call him and we would talk and he would say, “Oh, I’m watching these guys and they got the ball here and they’re kicking it around and the other guy’s trying to get it, and then they’re trying to get it to the other side.” And I would say like, “Daddy, are you watching soccer?” And he would go, “Oh yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.” But he couldn’t remember the word for soccer.

Rigo Hernandez: Looking back now, Alexis realizes that while her mom was alive, she was compensating for Alex. It wasn’t until after she died that a clearer picture emerged. Spouses compensating for each other is pretty common. The same thing happened with Evan’s mom. The first time she really noticed something was wrong was when her parents separated a few years ago. Evan realized that things weren’t moving forward with the divorce because her mom wasn’t doing the things she was supposed to be doing.

Evan: And she would forget, or she would get confused by the purpose, or she would do it kind of wrong, or she would get really upset about something and it would hold it up for weeks. It took me a little bit of time to realize that she just didn’t understand what was going on. I had been noticing changes in her memory for a long time at that point, probably for about 10 years, but it had never before that point seemed like something that was directly impeding her life.

Rigo Hernandez: Evan agreed to move to Boston for a few months to help her parents, but when she got there, she realized she was going to be there for much longer.

Evan: It felt like a huge crisis had been building up, and I hadn’t quite seen it in full. I had been feeling it under the surface, but when I got to Boston, I realized bills were not being paid. The house was—it looked like a hoarder’s house. It was super cluttered, but it looked like anxiety clutter. It wasn’t just years of things slowly accumulated. It was like paper obsessively hung onto and objects squirreled away. It didn’t seem rational or normal. That’s when I became concerned that my mom actually couldn’t live alone and needed a lot of help and my dad was not in a position to do that anymore.

Rigo Hernandez: It’s important to note that finding out your parent has Alzheimer’s or another kind of dementia is not the same thing as getting the diagnosis. Up until recently, the only way to do a definitive test was by taking a sample of brain tissue, but that’s so invasive that it usually doesn’t happen until an autopsy’s done.

Alexis Pedrick: It feels like by the time someone really says to you, “Okay, this is what it is and this is the name for it,” it’s the end. It’s on paper now that that is what happened, but it took a lot to get to that.

Rigo Hernandez: An autopsy revealed that Alexis’s father had vascular dementia, but when Alexis and her siblings were worried about her father and took him to the doctor, the diagnosis he got was something called mild cognitive impairment, which did not seem to line up with what Alexis and her brother were observing.

Alexis Pedrick: My younger brother had gone to California to visit some friends and came back and the house was in complete disrepair. [He had just started and stopped a bunch of things and sort of forgot in the middle of doing them. So we went to his doctor and we were like, “Something is not right.” And I remember him saying, “Well, he’s older. He probably has some grief that your mom died.” And I was like, “Yeah, I mean I guess he’s sad, but he cannot. … Ask him what he had for breakfast. He can’t tell you. Something is not right.” And I remember them saying, he told us that he had that phrase, “mild cognitive impairment,” and we were just like, “Okay, but this does not seem mild.” I would say about six months later he was in the hospital, like that was it.

Rigo Hernandez: Lanng got the same diagnosis, mild cognitive impairment.

Evan: Mild cognitive impairment is a really slippery diagnosis. I believe it is defined as cognitive impairment that does not include impairment of the activities of daily living. They’re very physical. The activities are things like toileting, feeding oneself, clothing oneself, basic hygiene, and mobility.

Rigo Hernandez: Evan went to get her mom tested in 2018. The test is a long list of questions to measure what they remember. Her mom scored a 26 out of 30, which is technically considered normal for a 71-year-old.

Evan: The only word that my mom heard was “normal,” so what I took from that was, “Something here is wrong. We don’t know what it is. We can’t actively pursue treatment because there are things under experiment, but there’s very little in the way of drugs or treatments that are definitively recommended by doctors. We are just going to have to wait and see what happens. Wait for things to develop, keep track, keep checking in. And what my mom heard was almost a vindication.” Like, “Evan is accusing me of having a bad memory, but the doctor says I’m normal.”

Rigo Hernandez: After getting that diagnosis, Evan wanted something more conclusive, so she scheduled another meeting with a more specialized neurologist. Evan told the doctor about her mom’s memory lapses, and then he gave her mom a bunch of tests.

Evan: And then I left and I went to a waiting room. And I ate string cheese for hours. I wanted to get bad news because what I had gotten so far was no news, and that made us both feel like we were floating, I think. But especially me, because I knew I was responsible for planning and taking care of her, and I couldn’t plan if I didn’t know what to expect. And mild cognitive impairment does not give you a lot of information about what to expect. And if we had a word like Alzheimer’s in our shared vocabulary, that is scary but concrete; it would allow us to have frank conversations about money and time and her wishes, her priorities. And all of that stuff is really difficult to create a conversation around when you don’t have a concrete reason to do it. And she was pushing it off, and she was getting angry if I brought it up because she felt like I was saying she was stupid or that I was saying she was incompetent. So I was hoping for bad news so that I could force the conversation.

Rigo Hernandez: But instead she got the same diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Again.

Rigo Hernandez: How did you feel when you were told that? Can you remember that day?

Evan: Yeah, I think I cried in the office. I felt like a monster. I mean, getting mild cognitive impairment as the diagnosis in some ways should have been the best news we could have gotten because it signified no development. We’d had the diagnosis in February of mild cognitive impairment and then it was late October. And to get the same diagnosis should have been great news. But what it meant to me was after all of this waiting, we still didn’t have better information about the cause of her symptoms or what happens next.

Rigo Hernandez: Like we said, getting an accurate Alzheimer’s diagnosis is hard and invasive. One method involves taking a sample of spinal fluid and looking for the accumulation of two proteins, amyloid and tau. Lanng ended up getting a spinal tap this past spring, but she only got this procedure because she was in a clinical trial. It confirmed that she has probable Alzheimer’s.

Evan: Hearing that information, that she almost certainly has Alzheimer’s disease, but knowing that she wasn’t processing that with me, meant that I kind of had to sit with the weight of that alone. And it felt like mine, and I knew that I’m going to see her go through that in a way that she’s not even going to see. I have to experience that sadness for her.

Rigo Hernandez: Alexis didn’t have the long, slow experience of Alzheimer’s that Evan is living through with her mom. Remember, Alexis’s father didn’t have Alzheimer’s; he had vascular dementia, and one of its hallmarks is how quickly it progresses.

Alexis Pedrick: When we got to the hospital and the hospital was like, “Oh yeah, this is probably vascular dementia.” And they were saying like, “Oh, you know, he’s got to go into a facility or he needs round-the-clock care, like he cannot … he cannot go home.” And they were talking to us as if we already knew or as if we should have been prepared. And I remember my older brother stopping them and saying, “Wait, what is dementia?”

Rigo Hernandez: Things with Alexis’s father built up until it reached a crisis point in 2011. He’d had a stroke and got into an accident, but he forgot that he’d been in an accident and kept driving. When the police caught up with him, he didn’t know who he was.

Alexis Pedrick: He didn’t know anything. And he had my business card in his wallet, and he knew that he had a card for someone in his wallet, someone they needed to call. I don’t think he … He couldn’t even articulate that I was his daughter. And so they called me and they took him to the hospital, and I called my brothers and we went there. My dad was, he was scared and he was crying, and I think now we sort of think about it and it’s like, “Oh, his life was over at that point. It was not going to go back to the way that it was.”

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Two—Living with Alzheimer’s.

Rigo Hernandez: There’s a theory about predictable stages of Alzheimer’s disease called retrogenesis. It says that the cognitive decline people with Alzheimer’s disease experience are the reverse of the milestones infants reach. Neurologists, Barry Reisberg came up with this theory in 1982.

Barry Reisberg: This is the reversal in this can be seen as the last stage of life.

Rigo Hernandez: While observing Alzheimer’s patients, he realized that the timeline of their decline mirrors infants’ timeline of growth, from birth until age 19.

Barry Reisberg: That timeframe is about the same timeframe that it takes us to acquire our abilities. And in the course of our development.

Rigo Hernandez: Between 4 and 12 weeks old, babies are able to hold up their heads. At around two months, they learn to smile. At around six months, they learn to sit up, and in about a year, they learn to walk, and so on and so on until they are productive citizens. But if you reverse this timeline and put it on the other end of the life span, that’s what happens with Alzheimer’s disease.

Barry Reisberg: And that is what retrogenesis is. We lose our abilities in approximately the same order, over approximately the same time in the course of the degenerative dementia of Alzheimer’s disease as we acquire these same abilities in the course of our normal human development.

Rigo Hernandez: I was really struck by this theory, so I told Evan about it, who was less excited about it than I was.

Evan: Wow. I can’t tell if that’s beautiful or sick.

Rigo Hernandez: Reisberg broke up Alzheimer’s into seven detailed stages. Mild cognitive impairment is stage three.

Barry Reisberg: People emerge in the seventh stage with very limited speech abilities. And then, we can frequently identify a single word substage. So it may be “yes”; it may be “no” when they mean “okay.” If they’re angry or upset, they may say, “Okay, okay,” or whatever the final word is. And then the ability to say even this final single word is lost. So these people in the seventh stage of Alzheimer’s disease really require the same kinds of care, the same amount of care as an infant. Some people, if they get the proper care, people can still at least internally have a comfortable life until the end, internally, in their own minds, and people need not suffer.

Rigo Hernandez: I think it’s important to note that the Alzheimer’s Association doesn’t buy the idea of the seven stages, because they think it creates false expectations for caregivers. And they think that each case of Alzheimer’s is unique.

Fredericka Waugh: I’m Fredericka Waugh, and I’m the associate director for diversity and inclusion for the Alzheimer’s Association, Delaware Valley Chapter.

Rigo Hernandez: So instead, they talk about early, middle, and late stages.

Fredericka Waugh: Because a lot of times the behavior and what they’re trying to manage overlaps, you know you they may be in stage 2 with some stage for us, you know behaviors also, so we don’t like to get hung up on that. However, it would be great if we could, but no one is going to go from stage 1 to Stage 7, you know step by step by step.

So if they’re looking at a pattern then, that’s going to make them a lot more frustrated because the person they’re taking care of may not fit the pattern, probably will not fit the pattern.

Rigo Hernandez: But Barry Reisberg says that breaking down these stages can be useful for caregivers, and Evan agrees that the predictability can be helpful.

Evan: Caretaking as an emotional undertaking is something that you have to prepare yourself for, and that takes so much out of you that seeing where a thing is going, even though it can be ugly, really ugly, knowing that it’s going to hit that point can help you get used to the idea that you’re ready for that before it hits.

Rigo Hernandez: So maybe the stages are helpful for caregivers, but there are other things that families do to manage. I asked Lanng if there were some things she writes down in order to remember.

Lanng Tamura: That’s very seldom that I write down things like that.

Evan: I write a lot of notes for you. So that’s why I got the whiteboard on the refrigerator, so I can write things down to remind you of things.

Lanng Tamura: Yeah.

Evan: And remember that FAQ that I wrote for you when we were dealing with the car insurance last week?

Rigo Hernandez: The week before I showed up, Lanng’s car had been hit by another car while it was parked.

Evan: You had a lot of questions about how we were going to buy a car and who was paying for the old car and whose insurance company was which. And so all the questions that seemed to come up a lot of times, I wrote down the question and the answer, and I gave you a two-page document that had all the questions and answers and I made you read it a lot. And then every time you asked me a question, I would say, “Go check out the FAQ and see if the answer’s there, and if it’s not, then you can come back and ask me.”

Lanng Tamura: You know, I don’t remember that at all.

Evan: That was three days ago.

Lanng Tamura: Really?

Evan: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Rigo Hernandez: When Evan reminds you of stuff like that, and then you … It’s new to you, new information. How do you feel when that happens?

Lang Tamura: When I don’t remember that she told me about it or wrote it down or something?

Rigo Hernandez: Yeah, and then she tells you about it.

Lanng Tamura: Well, I feel kind of bad about it, because it just seems like such a drag to have to make notes for somebody else because they’ll probably forget. I mean, that’s just so boring.

Rigo Hernandez: For Alexis’s dad, writing things down was part of how he was compensating for his decline. She discovered a lot after he died by looking at the notepads he kept.

Alexis Pedrick: When I look back on stuff now, I can watch this progression over time. Right? Early on in his notepads, it’s notes about work and things like that. And eventually, it becomes these really explicit detailed schedules of what time he needs to leave the house and who he’s going to pick up and what they mean to him.

Oh. you have to go get Alex. Alex is your son. Alex is going to be at this place, etc, etc. It’s this level of detail. And so, you know, even though he doesn’t have the incident that, you know, puts him into the nursing home and whatnot … Like the crisis doesn’t happen until I think it’s like 2011/2012. For years before that he’s clearly losing track of things, and he’s coming up with all these sort of like workarounds.

Rigo Hernandez: One note stands out in particular.

Alexis Pedrick: He had written my mom a note, and he had done some kind of work, some sort of repair work or something he had gotten done for her. And he was telling her how much money it was, but he had forgotten what the word is for money.

And so he replaced the word “money” with scrunches, and it’s the craziest note, where you say, “Oh, you know, it was this many scrunches we owed and then 15 scrunches—you know, that’s so it’s a total of 127 scrunches.” And, you know, it was select stuff like that when you look at it and you go, “Oh, this was not just he was writing too fast. Like he did not remember the word for money, you know?”

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Three—The Caregivers.

Rigo Hernandez: Caregiving is hard. The emotional labor of grief is taking place in real time alongside trying to make arrangements for care and keep track of someone else’s life. I asked Alexis about this.

Rigo Hernandez: What did you feel like when you realized that your dad doesn’t know the word for money? What does that … that seems like a profound … that seems like a paradigm shift.

Alexis Pedrick: Rigo, I was so tired. Do you know what I mean? We were exhausted. It took everything to get him settled. You know? We didn’t know his social security number. We’re running back to the house and going through his mail and saying, “Does he have a bank account? Oh, well, where? Where is it?” I remember feeling devastated, but I also remember thinking, “Oh, I don’t have any time to actually think about this. I just, I don’t have any time.” At one point, they needed us to bring him more clothes at the nursing home or at the facility. My dad was a real dapper dude. He would wear pressed pants and button-downs, and a blazer and a cap. He would go to the pharmacy in a Stetson. You know what I mean? Here we were in Kohl’s buying him sweatpants and T-shirts, and we were thinking, “Oh my God, if he was in his right mind, if he was present right now, he would be so furious. He would be like, ‘What are you buying me?’ He would not be caught dead in a pair of sweatpants.” We laughed and laughed. We were hysterical about it, but it was underneath that, we also were like, “Oh, this is it, actually. He doesn’t need any of those clothes, any of that stuff anymore. He’ll never wear it. This is what his life is.”

So I think you laugh because if you don’t laugh, you’ll cry, and you don’t have any time to cry because you’re just trying to figure your way through it. You just don’t have any bandwidth. No one prepares you. You sort of know, okay, they’ll forget who you are. No one prepares you for the fact that it’s a terminal disease, that this person is dying, that he, yes, will forget names and places, but eventually he will forget how to walk and he will forget how to talk, and he will forget how to breathe, and that this is the way that he will die. You put it in a box that you are going to have to process later because when you are taking care of somebody, even if you’re not live-in full-time taking care of them, it’s all consuming.

Rigo Hernandez: Evan is experiencing that all-consuming feeling, too. Back in Boston in the apartment she shares with her mom, Evan is showing me her Trello board. It’s an app that people use in offices to organize team projects. In fact, we use a similar app to produce this podcast, but Evan is using it to organize her mother’s life.

Evan: It feels a lot less like being someone’s daughter than being their project manager.

Rigo Hernandez: Evan is trained as an archivist, and she’s tracking her mom’s regression in a similar way to how she once organized archives.

Evan: Resources for deep future and progression are things that are not at all relevant yet, but are going to become an issue later—so driving safety, which actually now I’ve scheduled her an appointment for an evaluation for driving safety. I then keep a list of developments. So anytime there’s a new type of occurrence that seems to signal a new level of progression, I make a note about it with a note about the date. Not remembering the name of the neighborhood that we live in or mixing up nouns that are really common or central in her life or incidents like not remembering that I’m her daughter, thinking I’m her sister, things like that.

Rigo Hernandez: How does it feel to enter things like this as data points, things like your mother forgetting who you are?

Evan: It feels really absurd to try to make meaning out of it in any other way because it’s not meaningful. It’s just painful. It’s not her fault, and it’s not something that she did to hurt me, and yet I am hurt and I can’t blame her, and I shouldn’t try to assign blame anywhere. So to put it somewhere as a data point makes it feel important.

Rigo Hernandez: This is one of the hidden costs of Alzheimer’s. The price tag on the disease is about $290 billion a year, but it also costs about $234 billion in unpaid care time for people like Evan. The job Evan is doing is extremely hard. Professional caregiving has a turnover rate of 82%. That means that almost everyone who does it ends up quitting.

Evan: It’s hard to find the rewards because it just gets worse and worse and worse for every person that you’re attached to until they die.

Rigo Hernandez: Here’s another stat. Half of caregivers are depressed, and 40% of them die before the person they’re taking care of does because they are not taking care of themselves.

Evan: I think my new idea about self-care is that it’s not about meeting your needs; it’s about recognizing your needs because the truth is that sometimes I can’t meet my needs. It’ll be a week or two, and I won’t have seen anybody that I care about in two weeks, other than my mom sometimes. No friends, not even my dad because there’s too much to do.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Four—The Virtues of Forgetting.

Rigo Hernandez: Alzheimer’s is a cruel disease without a doubt, but I wanted to find out if there was anything uplifting at all, if there could ever be some virtue in forgetting. It turns out sometimes there is.

Evan: Forgetting things is not just about loss. It can be an opportunity to revisit things. We focus so much on our past as the single element that most constitutes our identity, what we have done, what we have accomplished, where we came from. And instead of knowing ourselves only through who we have been, sometimes people with dementia are able to really live in the present in a way that our meditation and Zen-obsessed society is somehow failing to teach us how to do.

Rigo Hernandez: There was an unexpected side to Alexis’s father forgetting.

Alexis Pedrick: He and my sister, my older sister, didn’t really get along. It was sort of funny because by the time he was in the nursing home, he had forgotten what they even fought about. He forgot that they didn’t talk or that they didn’t get along. He was living in a perpetual state of now and maybe like three minutes from now.

Rigo Hernandez: Deborah Hoffmann is a filmmaker who chronicled her mom’s regression in the 1994 film Complaints of a Dutiful Daughter. She found humanity in the disease.

Deborah Hoffmann: There were some profound lessons in all this, and one of them had to do with staying in the moment. The other one was the nature of prejudice. I don’t think my mother had particularly racist ideas, but she certainly had homophobic ideas, and certainly was not happy that I was gay until she sort of forgot that was how she was supposed to be. It just seemed so clear to me that, “Oh, prejudice is something you learn from society.” It has nothing to do with what you actually feel or see or anything. As soon as she forgot that was how you’re supposed to be, she had no problems whatsoever. She was just—accepting is too mild a word—she was just thrilled with my relationship with Frances or any friends of mine she met. So I just thought that was a revelation.

Rigo Hernandez: Last year, Evan got a copy of the Beach Boys album Pet Sounds. Lanng became obsessed with a B-side track called “Sloop John B.”

Evan: She associates the Beach Boys, who were very popular when she was a teenager, with her youth. Yet she didn’t recognize the song. So it was old, and it was brand new to her at the same time. She listened to that song hundreds of times in the next several months. I got so sick of it, but it was so wonderful to watch her get into it every single time, almost for the first time. She became familiar with it, and she knew it wasn’t the first time she was hearing it, but she was able to access this pleasure in the repetition of that song that I think she wouldn’t have found before. She would dance in the living room, and she would invite me to dance with her. Those were really special moments.

My mom was a classical musician for a while, so classical music was a big part of her identity, and she was very invested in complex, or what she thought of and would describe as complex, music. To see her take so much pleasure in such a simple song was complicated for me. It was wonderful to see her joy, and it was also a very painful reminder of the changes she was undergoing. It’s hard to see both of those things at once sometimes.

Rigo Hernandez: Evan also plays music, the cello, and she started playing while I was visiting. Lanng was watching her play from across the room, and she looked so happy.

Evan: (music)

Lanng Tamura: Oh, I miss playing a lot. There’s nothing like music. You’re not supposed to get it. So the effort is not for you to get it. It’s just how human beings react to sound and harmony. It is such a part of my soul, and there’s nothing like music.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Five—What Cure?

Rigo Hernandez: While I was doing some reporting for this story, I saw this on the news.

CNBC: Biogen shares are tumbling this morning, this is big news. It comes after the drug maker and Japanese partner Eisai discontinued late-stage trials of an Alzheimer’s treatment that came after an independent data-monitoring committee said that the treatment is unlikely to meet its primary goal.

Rigo Hernandez: I asked Evan how this news made her feel, and the answer really surprised me.

Evan: It’s not something that I spend a lot of time following because it’s exhausting and it’s disappointing and because it doesn’t help me today. The people that I really respect as the heroes of this field are the people who do tiny, tiny acts every hour for people who are never going to see a cure and who are never going to be restored to their former states of thriving. But if you can calm someone down, if you can comfort someone, if you can provide respite or relief to someone who’s thoroughly exhausted from caregiving, those things to me are essential values that I think have been forgotten.

Rigo Hernandez: I had assumed that caregivers like Evan would be more personally connected to Alzheimer’s research, but Alexis echoed Evan.

Alexis Pedrick: When you think about the number of decades there’s been work done on this, I’m not working on that timeline. My timeline’s a lot shorter than that. I think there’s a huge gap. What is science’s job, right? Yeah, there’s a real strong argument to be made that science’s job is to do this, right? Do the clinical trials, figure it out, figure out the medications, work on the cure, do the research, et cetera, et cetera. Again, you need all of that. That’s important, but is there another job that science should have in working on the here and now? I wonder how much work is being done out there that could have made—while it couldn’t have reversed his dementia—could have made the things that we were suffering with, the things that he was suffering with, easier or more comfortable. Making it that it doesn’t ever happen, I mean, cool, but not the biggest thing.

Alexis Pedrick: You can start listening to Part Two now, where we’ll dive into the science of Alzheimer’s.

Distillations is more than a podcast. We’re also a multimedia magazine. You can find our podcasts, videos, and stories at distillations.org, and you can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. This story was reported by Rigoberto Hernandez and produced by Mariel Carr, Rigoberto Hernandez, and myself. The episode was mixed by James Morrison. For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Thanks for listening.

Part Two

CNBC: Not the news anybody was looking for this morning from Eli Lilly, putting out the results of a phase III trial of its Alzheimer’s drug. It did not meet the goals of that study. The failure rate in Alzheimer’s drug development is unfortunately extremely high, including at least nine late-stage clinical trial failures over the last decade.

Alexis Pedrick: Hi, I’m Alexis Pedrick and this is Distillations, a podcast where we explore the funny, weird, and serious ways science intersects with culture and history, and it’s all powered by the Science History Institute. This is the second chapter of a two-part series on Alzheimer’s disease.

In Part One, I took off my official Distillations hat and put on my Alexis the person hat. I shared some pretty personal stuff with you all about what it was like to take care of my father who had dementia.

In Part Two, I’m putting back on my Alexis, the host of this podcast, hat, and let me tell you, I’ve learned some things that I didn’t know or think about, or frankly cared about when I was actually living through it. Alzheimer’s research took off 30 years ago, but it’s seen one disappointment after another. Our producer, Rigo Hernandez reported this whole series, and he and I are going to tell you this part of the story together.

Rigo Hernandez: There have been hundreds of clinical trials, research costs in the billions, and yet 28 years later, there are zero drugs to treat the actual cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

Sharon Begley: There are four approved drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. But none of them affect the actual biology of the disease, and none of them bring any benefits to patients after a few months on the medication. It’s important to say that the brain is very, very difficult, and any brain disease is therefore extremely difficult.

Alexis Pedrick: That’s Sharon Begley. She’s a senior writer for Stat News, a publication that covers the biotech industry. After one high-profile failure in March 2019, she started making phone calls to scientists to figure out why.

Sharon Begley: Why are all of these very well-respected, very highly capitalized companies continuing to bring forth compounds into phase I trials, phase II, and then the very, very expensive phase IIIs and they simply don’t work? I mean, how much bad luck can there be? And that’s when a number of researchers—they said in Alzheimer’s disease more than any disorder that they’re aware of—a particular hypothesis has just dominated the field in a way that they had never seen before.

Alexis Pedrick: In this episode, we’re going to find out why there have been so many failures. We all know that the road to scientific discovery can be messy, but as we learned, and you may be surprised to find out, it can even be unscientific. As it turns out, once researchers adopt a hypothesis, they run with it, and that can leave very little room for alternative ideas. The establishment accepts the theory, and anyone who doesn’t fit the mold gets cut.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter One—Everyone Loves a Winner.

Rigo Hernandez: Alzheimer’s disease got its name more than a century ago from Dr. Alois Alzheimer. He observed a patient of his, Auguste Deter, at an asylum in Germany and saw that she had delusions and memory loss. After he did an autopsy in 1906, he stained tissues of her brain and noticed sticky plaques and tangles. These two markers have become the hallmarks of the disease ever since.

Alexis Pedrick: But after Alzheimer’s discovery, no one really cared about this new disease. Not until decades later in the late 1970s when scientists started considering the disease a public health problem and not just a side effect of being old.

Newshour: It’s been called the disease of the century, and it is now the fourth largest cause of death in the United States. Doctors do not know what causes Alzheimer’s disease nor how to cure it, nor even treat it.

Rigo Hernandez: Scientists set off on a race, and the goal was simple: find a hypothesis that could explain the disease, which could then lead to the ultimate prize, a blockbuster drug that would cure it. Stanley Prusiner is a neurologist who studies Alzheimer’s, and this is the way he sees the competition.

Prusiner: You know, in science, unlike basketball or football or baseball, there’s always another year passes and you have another chance to be first. When you come in second in science, it’s like coming in thousandth or millionth or whatever. It doesn’t make any difference. You’re either first or your last.

Alexis Pedrick: In science, as in sports, everyone loves a winner. And for good reason too. Today we live in a world where smallpox, rinderpest, yaws, polio have mostly been eradicated, all because someone or a group of someones discovered a cure.

Rigo Hernandez: The research for Alzheimer’s as we know it today, all started around the same time in the 1980s and 1990s. Prusiner himself theorized that infectious proteins corrupted the brain in a similar way that mad cow disease does.

His theory did not get traction. Another theory called the tau hypothesis focused on the tangles—one of the two markers that Dr. Alois Alzheimer first observed.

Alexis Pedrick: And there are several Alzheimer’s theories out there. But in this episode, you’re going to hear us talk a lot about two theories; the amyloid hypothesis, which has been winning the race since the beginning, and what’s called the virus or infectious agent hypothesis, one of the many losers.

Rigo Hernandez: The virus or infectious agent hypothesis says that the herpes 1 virus, the one that causes cold sores in your mouth and the one that the majority of adults have, lives on your neurons. Certain genes can activate the virus, thereby causing Alzheimer’s.

Alexis Pedrick: For the past 30 years, theories like prion, tau, and virus hypotheses all took a back seat to the big kahuna in Alzheimer’s research, the amyloid hypothesis. To understand what this hypothesis says, you have to know a little bit about how the brain works. Rigo, take it away.

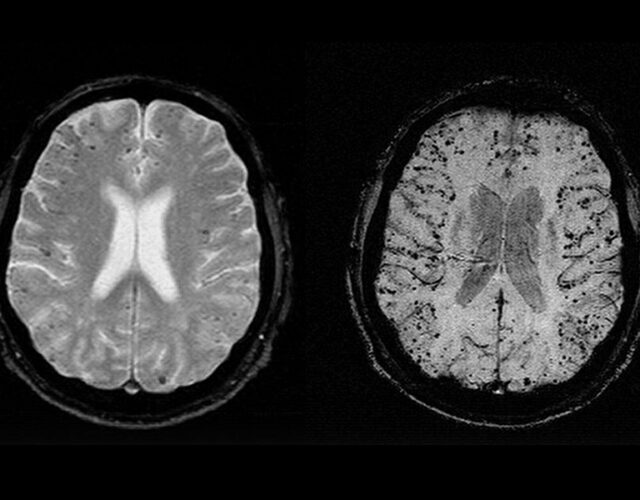

Rigo Hernandez: Okay, so inside our brains are very important cells called neurons. They’re the basic working unit of the brain. They process and transmit information throughout it. There are other types of cells that clear wastes away from your brain and keep the neurons healthy, and this is where the amyloid hypothesis jumps in. It says that floating around the neurons are a bunch of proteins. One of them is called the amyloid precursor protein, or APP, which does, well, we’re not exactly sure actually. But that APP generates a smaller protein called beta amyloid. In healthy brains, the beta amyloid gets flushed out, but in people with Alzheimer’s, they become sticky and accumulate outside the neurons. Those plaques are toxic to the neurons, and they eventually kill them.

Rigo Hernandez: In the early 1990s everyone was talking about Alzheimer’s and the amyloid hypothesis. It had cemented its place as “king” among the Alzheimer’s theories. Amyloid became a buzzword. Even PBS NewsHour was talking about it.

NewsHour: Where does extra beta amyloid come from? Why do some people have more of it in their brains?

This is still a matter of investigation, but the amyloid precursor protein itself is produced and influenced by a gene that regulates it; and one of the theories is there is a mutation in this gene that improperly instructs the amyloid precursor protein such that it abnormally produces the beta amyloid protein, which in turn causes damage to nerve cells.

Rigo Hernandez: John Hardy was the geneticist who found the mutation in the gene. They were just talking about it on the NewsHour. He thought that mutation must be causing the production of beta amyloid in Alzheimer’s patients.

John Hardy: I felt that genetics, if you like, was the referee. So genetics was going to referee between all the different hypotheses. When we found the mutation, I felt the referee called it for the amyloid hypothesis. That’s how I felt it, and I think that’s how everybody else felt it.

Alexis Pedrick: The referee definitely called it, even though it was still so early in the game. The result was that the amyloid hypothesis became the clear winner.

Rigo Hernandez: The following year John Hardy wrote an article that explained his theory of how Alzheimer’s is born. It goes something like this: over time, the buildup of amyloid reaches a critical mass, a cascade, that causes inflammation and the formation of tangles. Neurons start to die off, and this is what causes Alzheimer’s.

John Hardy: Let me just say that when I wrote the article, which is called the amyloid cascade hypothesis, I wrote that over a weekend, literally without thinking. I mean I really wrote it over a weekend and submitted it on the Monday or Tuesday after starting to write it on the Friday. It was never modified. We just sent it in, and to my amazement, it was accepted immediately. I didn’t intend it to be … I never intended the idea to be that it was like the 10 commandments handed to Moses, should be carved in stone, and everyone should read it forever and a day. If I had been told that when I wrote it, I would have thought that was ridiculous.

Alexis Pedrick: Nevertheless, the amyloid hypothesis was taken as gospel, and for the next 30 years, Team Amyloid gets all the funding, all the attention, all the resources. Meanwhile, other hypotheses like Team Virus lose out.

Rigo Hernandez: Chapter Two—Life at the Bottom.

Alexis Pedrick: If we treat science like a zero-sum game and place the amyloid hypothesis at the top as winner, then it follows that everything else must be to varying degrees the losers.

Rigo Hernandez: The virus, or infectious agent theory, pioneered by molecular neurobiologist Ruth Itzhaki, got especially rough treatment.

Ruth Itzhaki: I had a very naive idea that everybody in science were brothers and sisters and helped each other. Some people are like that, but they’re fairly rare. But I’ve certainly enormously enjoyed working in science. I think the intellectual stimulus is terrific. It’s just that the practical side is not always very terrific. In fact, it can sometimes be quite awful.

Alexis Pedrick: So what got her to go from naive, idealistic scientist into a hardened skeptic? It all started when she began researching Alzheimer’s in the 1980s. This is Sharon Begley from Stat News again.

Sharon Begley: So Itzhaki was a pioneer of the infectious agent hypothesis of Alzheimer’s, and she did this work, gosh, more than a quarter-century ago. It was not definitive, but it was certainly suggestive.

Alexis Pedrick: But from the onset, there was already an Alzheimer’s theory hierarchy. Remember, amyloid is King. Following that was the tau hypothesis, and pretty much any other theory was regarded with skepticism.

Ruth Itzhaki: It was just something so new, but of course that made it very suspect. When we tried to submit a paper on it, we had a great many refusals and disappointments and people saying it’s all … more or less saying it’s rubbish.

Rigo Hernandez: Still, Ruth Itzhaki submitted her research findings to science journals for years and years. In science, being published in journals is one of the main ways that you get your ideas heard by other scientists. If you don’t get your ideas into journals, they might as well not exist.

Ruth Itzhaki: I can’t remember how many journals we tried, but we certainly tried several. All of which refused it and not for any good reason, but mostly on the grounds that it was artifactual law. It was just ridiculous and couldn’t be possibly true, until we found the Journal of Medical Virology, which was a medium-quality journal.

Rigo Hernandez: The other way to get your ideas out into the science community is by giving talks at conferences. This was also an uphill battle for Itzhaki. In 2004, Ruth Itzhaki tried to give a talk at the big annual Alzheimer’s conference.

Ruth Itzhaki: I was told that it was apparently a huge battle to let them agree even to my giving a talk for 10 minutes.

Rigo Hernandez: Those 10 minutes were thanks to George Perry, a neuroscientist and editor of the Journal of Alzheimer’s. He’s also a prominent critic of the amyloid hypothesis.

George Perry: The only time I was ever on the program committee, I fought to get her a spot on the program.

Ruth Itzhaki: Which of course was one of many other 10-minute talks and therefore attended by a relatively small number of people. Although I do remember one person, very nice, some person stood up and said, “Really, people should be paying attention to this. It really is potentially very important.” I was very gratified and cheered by what he said then because it was so unusual to have that attitude.

Rigo Hernandez: Getting published only by second-tier journals, not getting to talk at conferences, experiencing hostility at conferences, these all had trickle-down consequences. It made it hard to get funding for her research. Itzhaki remembers one particularly frustrating rejection.

Ruth Itzhaki: They said we hadn’t done any animal work, which is totally true, we hadn’t. And the reason was, that particular organization we’d applied to three years earlier to do animal work had turned it down with a very, very nasty referee’s comments. So that was really in a way quite ironic, but that’s the sort of thing that has happened, and you can imagine that makes one feel rather bitter about it.

Sharon Begley: She tried to get funding and was rejected time after time after time, and that’s bad enough. But honestly I would have to say that the decision of journals, high-profile journals to reject her papers, the decision of meeting organizers not to give her a speaking slot, those are the sort of things that send a message, a sort of wink, wink message. Especially to younger researchers. That’s kind of a fringe idea. And guess what? People don’t succeed in science by pursuing fringe ideas. So people did not pursue it.

Ruth Itzhaki: So that went on for years and years, and it was quite dreadful, because such money as I got was from small organizations who were interested and willing to try something new, or occasionally from companies who wanted some experiments done. But even nearly always, in very short supply, was the funding. And the difficulty of getting published was a vicious circle because the fewer papers you produced, the less chance you had of getting anything or persuading other people. So, it’s just a self-perpetuating situation.

Alexis Pedrick: Self-perpetuating situation. That’s important. And not just from the point of view of Ruth Itzhaki’s theory but for science as a whole. Research needs competing ideas. If you have them all stuck in a loop somewhere, where they can never get heard, you risk missing something important.

Rigo Hernandez: Rachael Neve and Nikos Robakis are two scientists who contributed to the amyloid theory. They discovered the APP-creating gene. So Hardy discovered the mutation, but they discovered the gene. Well, it turns out that after doing more research, they changed their minds about the amyloid hypothesis.

Sharon Begley: So even people who were involved in the amyloid hypothesis subsequently, with more research, said, “You know what? Amyloid has something to do with this disease, that’s incontrovertible, but it is not the right drug target.” And when they tried to sort of deviate from the mainstream view, they really, really struggled.

Rigo Hernandez: Rachael Neve had a contact at the National Institutes of Health. They give out the lion’s share of funding for Alzheimer’s research, and this is what that contact told her.

Sharon Begley: Her contact at the National Institutes of Health said, “Look, regardless of what study you actually want to do, even if it has nothing to do with amyloid, just make up something to suggest that it’s at least amyloid adjacent, as we say these days. So that the panel that decides whether or not to fund a study will be more likely to say yes to it.

Rigo Hernandez: In an email, Neve told us that she quit the field of Alzheimer’s 11 years ago out of, quote, “disgust with the amyloid files domination of the field.”

Nikos Robakis is still in the field, but he’s critical of it.

Robakis: I support the fact that the amyloid theory was tested. Every scientific theory must be tested. Having said that, the NIA [National Institute on Aging], the NIH [branch] that really gives the money out, should also as I mentioned before, put some more support to alternative fields, and I think that was one point where the system failed.

Rigo Hernandez: He’s also changed his mind about the amyloid hypothesis.

Robakis: So of course it would be to my advantage for amyloid to be very important, but surely it became clear that there were a lot of facts, empirical evidence, refuting or going against the hypothesis that amyloid is the main cause of the neurodegeneration which causes Alzheimer’s disease.

Rigo Hernandez: You could have benefited from the amyloid hypothesis?

Robakis: Exactly, yes of course. But I could not go against my own thought, correct? That would be dishonest.

Rigo Hernandez: And once he started focusing on other theories, getting funding was much harder. He ultimately got funding, but he didn’t like the message this sent out to young scientists.

Sharon Begley: He described a number of junior scientists who worked in his lab, who saw what he went through struggling to get funding for anything other than amyloid and who said, “You know what? We don’t need this. We’re going to go study Parkinson’s disease or we’re going to go study the blood-brain barrier.” Important as Alzheimer’s is, in addition to everything else you have to struggle to do as a scientist, we just don’t need to fight this just very, very dominant force. So then you ask, these smart people left the field, if they had remained within the Alzheimer’s research community might we be further along than we are? That’s obviously unanswerable, but you have to think maybe we would be.

Rigo Hernandez: George Perry is a neuroscientist who got Itzhaki that 10-minute speaking slot, and he’s one of the amyloid theories most vocal critics. He’s written a couple of papers comparing the dominance of the amyloid theory to religious fervor.

George Perry: We dissect how amyloid became like religious phenomena and cult-like. And much like what happened 500 years ago, during Galileo’s and Copernicus’s time, in which the earth was thought to be the center of the universe. And if you reacted against that, you were attacked.

Rigo Hernandez: Chapter Three—What Makes a Winner?

Alexis Pedrick: From the beginning, being on Team Amyloid was very attractive. Everyone liked the amyloid theory because, well, like we said before, everyone likes a winner. But why amyloid? John Hardy, the father of the theory himself, might say it best.

John Hardy: Frankly, because it was simple. It was easy to write the arguments down in a convincing way, and it was therefore easy to sell within pharma and within academia.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember, the ultimate prize is a blockbuster drug, and clear winners are very attractive to pharmaceutical companies. George Perry, the perennial thorn in the side of Team Amyloid, agrees that the theory is simple, but he also thinks it’s wrong.

George Perry: I think it’s a misunderstanding of genetic evidence. People assume if they have a mutation that leads to a disease, that that means it’s causality. When in truth, genetic evidence is like many other kinds of evidence; it’s correlational. It doesn’t tell you mechanism without going deeper.

Alexis Pedrick: And listen, we all know the experience of sticking with an idea until the bitter end. It’s human nature. And although we forget sometimes, scientists are humans too, and they aren’t immune to that experience.

Sharon Begley: These were not people who had evil intentions by any means. Instead they truly believed, and I would say believe present tense, in their heart of hearts that amyloid is the right target to go after. Once a scientist is intellectually invested in a particular hypothesis, it is very, very hard for him or her to abandon it, not when that hypothesis has been his or her claim to professional advancement and consulting fees and advisory roles and prominent editorial positions in journals. People have ridden the amyloid hypothesis to great success in their personal, professional lives. Unfortunately, the amyloid hypothesis has not helped any Alzheimer’s patients.

Alexis Pedrick: And that’s not to say that amyloid has nothing to do with Alzheimer’s, but some scientists think that its actual role may be differ rent than we originally thought.

George Perry: If you’re an unknowledgeable person, which is what scientists start as when they’re studying things, and you hear that a fire’s burned down the house, and you run to the house and what do you see? You see firemen pouring water on the house, with their hooks tearing apart the house. If you didn’t understand the context, you would think that the fireman was the problem, because the arsonist is long gone. But if you understood the whole context, you’d know that firemen didn’t cause the fire and you’d know that there was something that happened previously. Maybe an arsonist, maybe a shorted wire. That’s what I think is the problem here, is that the amyloid is playing that role, much like the fireman is doing.

Alexis Pedrick: It’s not just about being right or wrong about amyloid. It’s more like, all those resources and the fact that the amyloid hypothesis has gotten the lion’s share of funding and attention, might lead you to believe that there have not been any problems, that amyloid dominated all of those other theories because it figured out the answer. But there have been lots of red flags along the way. The one thing that isn’t required to make a winner: being right.

Sharon Begley: But I have to say that the clearest red flags along the way have been the failures of the amyloid-targeting experimental drugs. With failure after failure, you would think more people would’ve said, “Maybe this is not the way to go.”

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Four—The Winner Is Losing, Clinical Trials and the Search for the Cure.

Clinical trial explainer: The Clinical Trial Journey is how a medical intervention, such as a drug, device, or procedure, moves from an idea into patient care.

Rigo Hernandez: After Team Amyloid researchers convinced pharmaceutical companies to pursue their hypothesis, they went to work developing a drug that would target the amyloid protein and stop Alzheimer’s. The first clinical trial was 20 years ago. This is an explainer from Stat News, the side Sharon Begley reports for.

Stat News Explainer: So the first big idea was a vaccine. So just as injecting someone with an inactive virus can prevent them from ever getting, say, polio, the idea was that if you stick people with a synthetic amyloid, you would train their immune systems to find and hunt down amyloid in the brain and basically treat Alzheimer’s naturally. And that’s where our timeline of amyloid failure begins.

Rigo Hernandez: Over the years, trial after trial based on the amyloid hypothesis has failed. Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer have all taken stabs at it, and one by one they failed.

CNBC: Not the news anybody was looking for this morning from Eli Lilly, putting out the results of a phase III trial of its Alzheimer’s drug, solanezumab. It did not meet the goals of that study. As a result, Lilly says it will not seek regulatory approval of this drug.

Rigo Hernandez: Yet, over and over again, instead of giving up completely, the trials continue, and an interesting thing happens. Each time they fail, they pivot, and one big idea emerges. What if it’s too late for some people? What if they were only to focus on people that haven’t developed the amyloid plaques yet?

Sharon Begley: In retrospect, the companies as well as just outside scientists said, well, look, a lot of the people they enrolled, it turns out did not have amyloid in their brains, and if you are giving them an anti-amyloid compound, then somebody who doesn’t have amyloid is not going to be affected by it, has no chance of benefiting from it, and arguably did not have Alzheimer’s disease in the first place, because the amyloid deposits are the hallmark of the disease.

Rigo Hernandez: Reisa Sperling is a leading researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and a leader in the Alzheimer’s research field. She was a principal investigator in the trial by Janssen that failed. She says this is what she learned from that trial.

Reisa Sperling: Our research started to show that we needed to go quite early, and I really thought that we should be starting 10 or 15 years before symptoms, and that’s really where my research has been focused in the past 15 years.

Rigo: George Perry says these are just excuses for a failed hypothesis.

George Perry: She was advocating earlier, earlier interventions, and I suggested that we needed to start in utero. I did not do so seriously. Because it’ll never stop, and if it doesn’t work in utero, that could be that you need to start while people are dating. I don’t know. Or you need to look at their grandparents, because all of those things that impact people … how your grandmother … what they ate, what they did, and whether they were educated actually impacts your genes. So all those things are intervening, but how are you going to do those tests? With current technology and current understanding, it just becomes really difficult.

Rigo Hernandez: Despite the failures, Team Amyloid keeps getting the green light to keep going. They do more clinical trials until we get to the biggest, THE clinical trial of them all, Biogen’s aducanumab. They learned from all the previous mistakes and were highly touted as a good trial.

Sharon: Biogen was really smart. It made sure that their patients had a significant amyloid burden, as it’s called, in the brain. And they did something else. The field has recognized that once somebody has severe Alzheimer’s, it is almost certainly too late for them to benefit by having amyloid removed from the brain, and that’s because they already have lost synapses. Their neurons are dead, neurons are not going to come back from the dead. Therefore, all the smart thinking said, “You have to try to treat patients who have only mild, possibly moderate Alzheimer’s.” And again, that is what Biogen did. So they enrolled only mild to moderate patients, and they made sure they had amyloid.

Rigo Hernandez: And at first, it looked like things were going great.

CNBC: It’s been a really exciting morning for Biogen and the whole medical community today, with these positive data on Alzheimer’s disease. Analysts saying, after seeing the data, they met and exceeded these high expectations, showing not only a reduction in the amyloid plaques in the brain that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease, but also a slowing of the cognitive declines you see in Alzheimer’s. Very strong signals on all of those, so people are very, very excited.

Rigo Hernandez: When the results of the phase I trial were published in the journal Nature, it led to articles proclaiming this might be the Holy Grail for Alzheimer’s, but then this happened in March of 2019.

CNBC: Biogen shares are tumbling this morning. This is big news. It comes after the drug maker and Japanese partner Eisai discontinued late-stage trials of an Alzheimer’s treatment. That came after an independent data-monitoring committee said that the treatment is unlikely to meet its primary goal.

Rigo Hernandez: Biogen ended those phase III trials after it showed that their compound was no better than placebo. It was a huge blow.

CNBC: This is very bad news, not just for shareholders in this, not just for the company, but also for anybody who was really hoping on this as a new way to try and treat Alzheimer’s. So the company CEO coming out and saying, this is just proof of how difficult it is to try and tackle Alzheimer’s and how we really need to focus much more on neuroscience and ways to come at it. So a lot of people are going to be waking up to some very disappointing news this morning.

Rigo Hernandez: By the time Biogen’s trial started in 2012, Team Amyloid’s captain and founder, John Hardy, was already getting nervous. There had been so many other failures.

John Hardy: I thought it was going to raise hopes inappropriately, and that’s what it did. And so when it failed, I just kind of rolled my eyes because that was what I was worried about right from the get-go.

Sharon Begley: So Biogen seemed to do everything right, and still their lead compound failed and that made people think, well, wait a minute, if doing everything right in a clinical trial and a compound as effective at getting rid of amyloid as [inaudible 00:30:36] is, if that doesn’t work, what is going on here?

It’s not just that the trials are set up in the wrong way. It’s not just that they’re going after the wrong patients, but there might be something fundamentally wrong with the amyloid hypothesis.

And then the next question is, well, why are all of these trials that we’re hearing about focused on amyloid? And that’s when the answer came. It’s just really, really been hard, if not impossible, to do any research outside the amyloid hypothesis.

Alexis Pedrick: It makes sense that scientists who have devoted their careers, their lives to this one theory wouldn’t want to give it up, but you might be wondering why would pharmaceutical companies continue to pour so much money into a theory that is not delivered?

Rigo Hernandez: Yeah, we went through that too. I asked Sharon Begley exactly that.

Sharon Begley: If anybody comes up with an even slightly effective Alzheimer’s drug, it will be a multibillion-dollar jackpot for them because again, huge unmet need. Something like 6 million people currently have the disease, more people getting it every year. So the market would be huge, and as we know, even by chance alone, sometimes something that is actually not effective, if you use the standard statistics of 0.05, even something that’s not effective could appear to be effective.

And a number of scientists said to me, “You know what? One of these days there’s going to be one of those studies, and there’ll be such pressure on the FDA to approve the compound, again because there’s nothing else. So a company might have a commercially successful drug that is medically and scientifically a failure. And people won’t know it until they’ve made a lot of money.”

That’s a really, really cynical way to look at this. And I am not endorsing it. I am simply relating what some people have hypothesized to me. But the other explanation is if you are sitting at a drug company, you cannot go wrong if you’re a mid-level or even a high-level executive by following what everybody else is doing. If your amyloid compound fails, as they keep doing, you can say, “Look, we gave it our best shot, but you know those guys over there, theirs failed too. So it’s not like we did something obviously wrong.”

So everybody could sort of seek cover in their competitors’ failures. When Biogen failed, they could say, “Oh, but our trial was even better than the ones that Merck did. So we really, really tried, and we did it smarter, but oh, well.”

On the other hand, if you are again, a mid-level executive and you green-light something that is not within the academic mainstream and your trial fails, you have lost your job.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Five—The Reckoning.

Rigo Hernandez: Each year there’s a big Alzheimer’s meeting that everyone in the field goes to. It’s the one where Ruth Itzhaki couldn’t get a speaking slot in 2004. George Perry went this year in July 2019, just a few months after Biogen’s failure, and I asked him if there was anything different than other years.

George Perry: I think it differed from other years in that there were no major clinical trials that were reported at the meeting. All of them had failed prior to the meeting, and they had been announced prior to it. Aside from that, I think that people were really questioning where we go from here.

Rigo Hernandez: The many clinical trials have caused some reckoning among researchers. Even John Hardy, the father of the amyloid hypothesis, finds it humbling.

John Hardy: I think that you’ve got to take the evidence. So of course I take these failures absolutely seriously, and of course they have made me change my views. A lot of the early trials were crap, but these later trials have not been crap, and they have failed and so that is a concern.

Rigo Hernandez: People who are critical of the amyloid hypothesis say that their proponents are pushing this as a belief system, as a religion.

George Perry: A key part of science, as opposed to religion, you have to always … each thing you know, you never really know. It’s always susceptible to change and validation by experimental observations, and if things don’t fit your hypothesis, you have to modify your hypothesis to fit eventually and provide guidance for future questions. When you don’t do that, you’re not doing science.

Rigo Hernandez: At this year’s Alzheimer’s conference in Los Angeles, something unexpected happened. Ruth Itzhaki, the scientist who got shunned for her work on herpes and Alzheimer’s, got a speaking role. After more than 25 years, there appears to be some soul-searching among the community and a willingness to accept new ideas.

Ruth Itzhaki: This year I was very surprised, and I must say pleasantly surprised, very surprised to be invited to give a talk. I was very pleased because it was the first time it had ever been aired, and we had a good audience. And I think I’ve got the impression as much as one can that people were really very interested.

Rigo Hernandez: Sharon says that finally the latest failed medical trial might have changed things for Itzhaki. Her work is now being rediscovered after all these years. It’s bittersweet.

Sharon: Unfortunately, that’s the kind of thing that could have been done at least a decade earlier if people like Itzhaki had not been dismissed the way she was.

Rigo Hernandez: I asked Ruth Itzhaki if she feels vindicated.

Ruth Itzhaki: Oh, I feel very, very much vindicated because there’s such a lot of supportive evidence by quite different sorts of methods. I feel very much vindicated now, as you said, and I don’t think I’m bitter.

I’m just feeling somewhat cynical about people’s motives sometimes, and just looking back I think it was partly a dismal time, but thanks to the people who work with me and a few supporters who came out to help, it was marvelous that some people were willing and able to do that. So I certainly try not to be embittered, and I hope I don’t sound like it.

Rigo Hernandez: One of the most common refrains from people in the amyloid camp is that there just wasn’t enough money to go around.

Sharon: Well, every scientist in a field says there’s not enough money for his or her field, which is true. On the other hand, you could also look at people who controlled the purse strings, and their choice was to direct virtually all of what funding did exist toward this one hypothesis. So it’s rarely a good idea to put all your eggs in one basket, but that’s pretty close to what the Alzheimer’s field did.

Rigo Hernandez: Some are not as forgiving to the failed clinical trials. This is John Trojanowski, the tau theory guy.

John T: I think it’s almost criminal that we as scientists allowed this to happen. That money could been have put to use for a lot of other things to help Alzheimer’s patients.

Rigo Hernandez: But Hardy says he has no regrets about pushing for the amyloid hypothesis.

John Hardy: I don’t feel responsible. In a negative sense, I don’t feel, oh my God, I’ve misled everybody. I just laid out the arguments, and it’s, yeah, I made a … just laid out the article on arguments.

Sharon: I think those of us who are outside science but who pay attention to it, and probably young people who are thinking of going into science, view it, at least initially, as a pure meritocracy where the best ideas win out, where best is defined as the most rigorous evidence in its favor.

And it’s not very much subjective but that really what’s right will emerge. And to see instead that other ideas are censored and quashed and people are just beaten up until they can’t take it anymore … I know from the younger scientists who wrote to me after the story, that was definitely eye-opening and really discouraging.

Alexis Pedrick: So where does this leave us?

We started this story by talking about the patients and their caregivers. People like Evan and her mom, people like me. We know there is a disconnect, and it’s one we’ve been trying to reconcile in our brains, or I should say it’s one I’ve been trying to reconcile in my brain.

And after working on the second part of this story and talking to Rigo about all of his reporting, I’m actually filled with compassion. Compassion for all of those researchers who have the hard, maybe impossible job, of trying to understand a disease that is in undeniably the most complex part of the body: the brain.