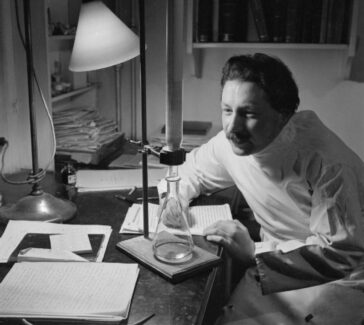

Calvin Ross Sperling

Sperling was a plant explorer who dedicated his life to preserving biodiversity through seed banking for ecological and agricultural purposes.

What are a plant explorer’s favorite foods? When Calvin Sperling (1957–1995) was asked about this in 1991, he recalled the bread that had been served to him in southern Turkey by a couple struggling to harvest their wheat after a drought and the wild apricots he found and brought back from Kazakhstan in his tattered suitcase. He looked ahead to U.S. grocery stores stocked with red carrots, purple potatoes, and burgundy beans.

But Sperling’s life was cut short by cancer, and he did not live long enough to witness these developments. At the peak of his career, from 1987 to 1994, he served as chief plant explorer for the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. This gave him the opportunity to collect and preserve unique plant germplasm that was used to increase the genetic diversity of crops around the world. This legacy, alive in the plants he studied, survived well beyond his 38 years.

A Growing Love of Plants

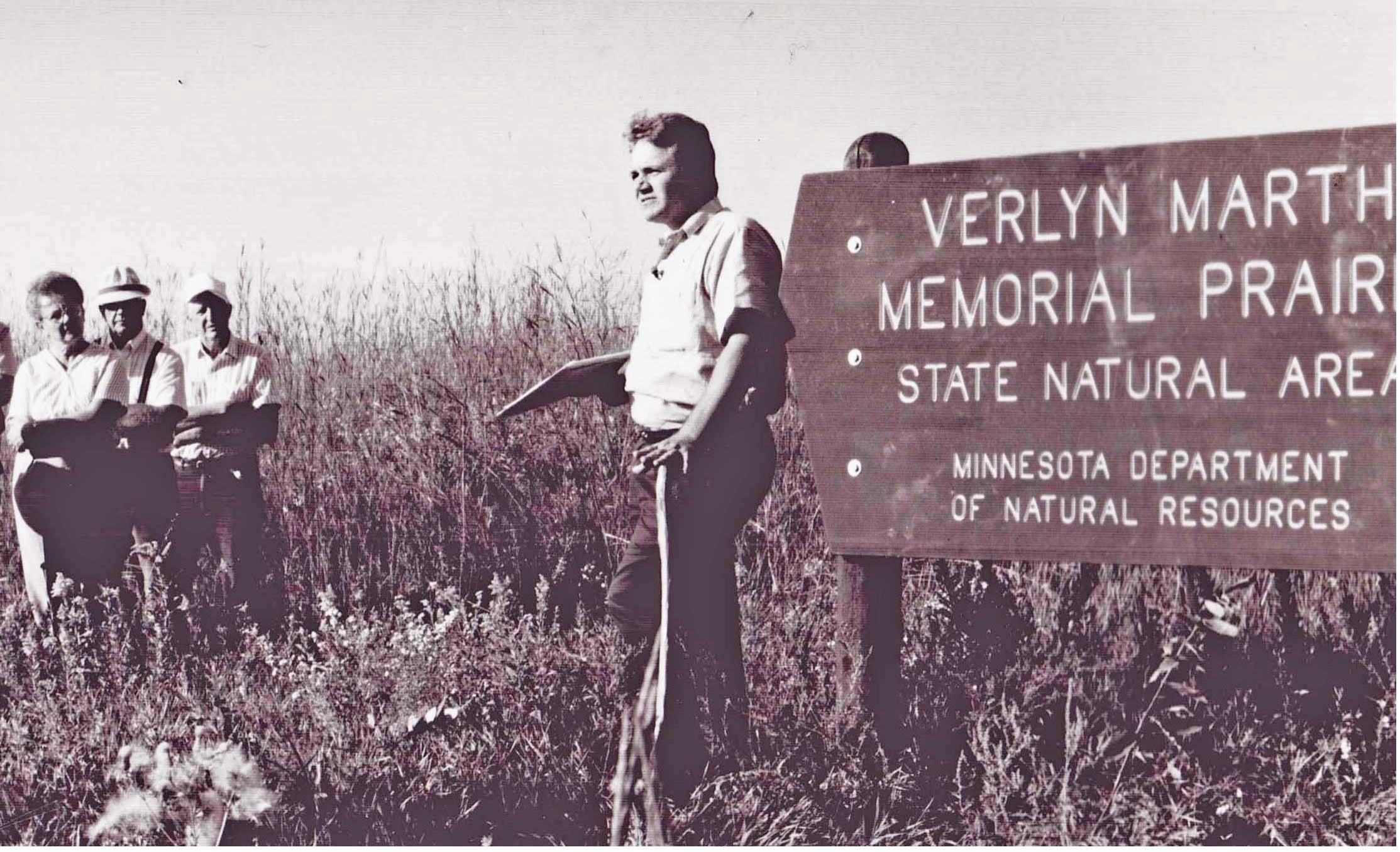

Farwell, Minnesota, had roughly 100 residents in 1957, the year of Sperling’s birth. His family home was a working dairy farm. In addition to farming, his father was employed as a county agricultural inspector—it was his job was to monitor local roadsides for weed infestations. As a boy, he accompanied his father on his rounds, gaining practical experience in plant identification. Quite often, his father said, “Calvin would ask the man driving the truck to stop” so he could climb out and “collect some plant specimen.”

Such experiences complemented Sperling’s growing academic engagement with plants. His family had a subscription to National Geographic and was greatly influenced by The World in Your Garden, part of the National Geographic Natural Science Library. In high school, he learned how to collect and dry plant specimens. He became active in 4-H around this time, and his interests spread from livestock and plants to rocks and minerals. His parents supported these interests, and they “fixed up a little room in the basement” where he could work on his collections.

Sperling was indecisive about higher education at first, but his mother, Doris, convinced him that it would help, not hinder, his desire to study plants. He was accepted to North Dakota State University in 1975, where he became a curatorial assistant in the campus herbarium. By the time he graduated in 1979, he had helped collect thousands of specimens for the herbarium, which formed a nearly complete inventory of Minnesota flora. These specimens were a valuable teaching tool, and part of his job was to manage their distribution and use. A successful student, Sperling’s advisors encouraged him to continue his education. He secured a scholarship to pursue economic botany at Harvard and left the Midwest for Cambridge, Massachusetts, shortly after completing his undergraduate degree.

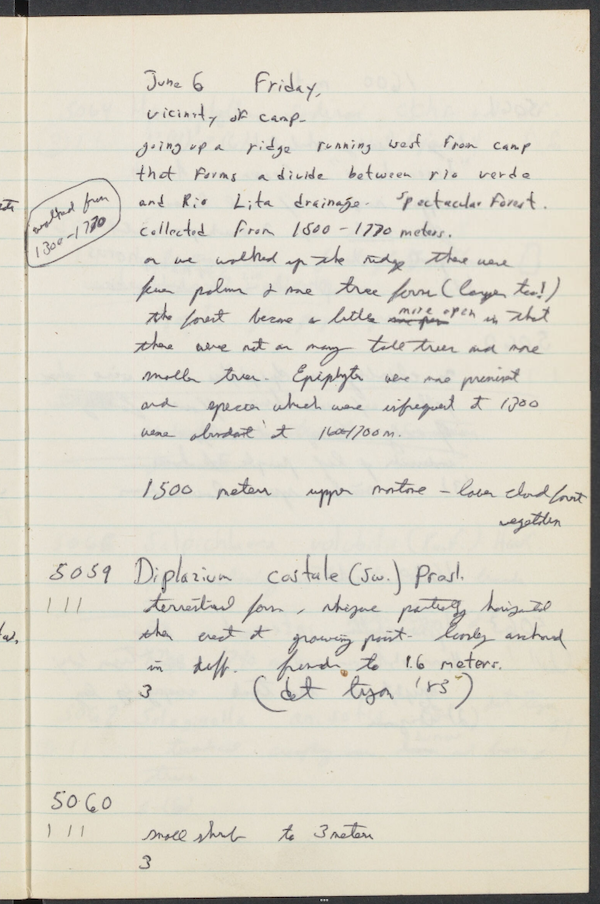

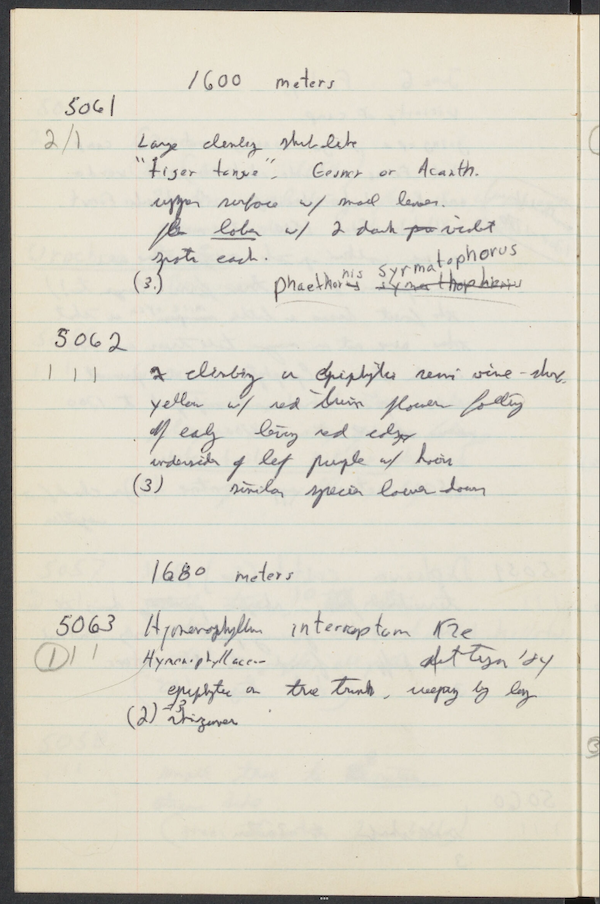

Pages from Calvin Sperling’s field notebook showing how he identified plants and recorded information about their location, 1980.

The World Seen Through Letters Home

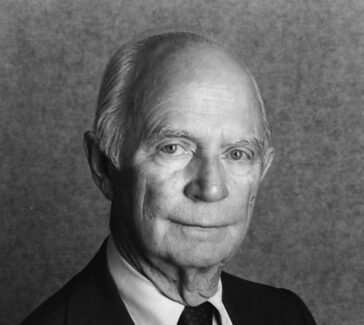

Sperling found a dedicated mentor in Richard Evans Schultes (1915–2001), a professor who specialized in ethnobotany. Schultes was especially interested in the ways indigenous groups in the Americas used hallucinogenic plants, but his research shifted towards economically significant crops—sources of food and rubber, for instance—during World War II. Calvin completed his master’s degree under Schultes in 1981 and set to work on his PhD dissertation, which focused on the Basellaceae family, some species of which were known to be a significant source of food in the Andes in South America.

During his fieldwork in the summer of 1982, Sperling wrote long letters home that were addressed to everyone in the family. His father would type them up and send them to every addressee. “Through his eyes,” his niece, Natasha, later recalled, “we were all able to share in his experiences and travels.” Sperling made detailed observations on agricultural practices in South America. In addition to the descriptions he recorded in his dissertation and letters, he brought back over 200 plant specimens from his fieldwork for the Harvard University Herbarium and the National Plant Germplasm System.

The plants Sperling collected during his graduate studies with Schultes were added to the Gray Herbarium of Harvard University, totaling over 50 species. These collections were richly documented, providing information on research methodology and the geography of each plant. The dissertation he was working on at this time was never published, but it proved key to understanding the Basellaceae. Upon its completion, his focus shifted from this individual plant family to strategic gaps in the National Planet Germplasm System. Sperling turned to this work full time in 1987, when he left Harvard for the USDA.

Global Biodiversity Conservation

Significant developments took place in the history of plant conservation during Sperling’s career at the USDA. First, he witnessed the founding and integration of local, national, and international gene banks via the internet. Second, he worked at a time when awareness of global environmental concerns and effects was growing. Third, plant scientists began to adopt the new tools of biotechnology during this period. Finally, a new value system was ascendant—one that no longer viewed genetic resources as the common heritage of humanity, heritage meant to be openly shared.

Sperling’s work as the chief USDA plant explorer took him all over the world during the final years of the Cold War. He traveled to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, both in the former Soviet Union, to collaborate with Aimak Dzhangalievich Dzhangaliev (1913–2009). The two biologists investigated remote forests populated with Malus sieversii, wild apples unique to this area along the border between Russia and China. Sperling was remembered for his ability to communicate easily across cultural and linguistic differences on such trips. He was later remembered by colleagues for promoting “international relationships in the era before international treaties for…the exchange of plant genetic resources became common.”

The tools of biotechnology, which made it possible to identify genes with newfound precision, brought concerns about the free availability of plant germplasm. Between 1986 and 1990, it became possible to add genes collected through fieldwork to the otherwise complete genome of a given plant species. This meant that what had once been considered part of a universal “genetic resource” could now be patented and protected in commercial seeds that were sold for private gain. With the United Nations Framework Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992, genetic resources were reconceptualized as the sovereign resource base of a given country. A nationalized approach replaced that of common heritage.

Sperling became involved with an initiative known as “Project Noah” around this time. It focused on three objectives: identifying threats to global biodiversity; promoting the science and technology necessary to advance the preservation and storage of genetic resources; and supporting an emerging international political consensus that healthy plants are indispensable to human development.

As part of his work at the USDA, Sperling created new guidelines for the collection and exchange of plant germplasm that aligned with the new understanding that genetic resources were a matter of national sovereignty. This guidance was eventually codified as the USDA’s Code of Conduct for Foreign Plant Germplasm Collecting and Transfer.

LEARN MORE

Calvin Sperling was awarded the Frank N. Meyer Medal for Plant Genetic Resources in 1995, the year he died. The inscription at the center of the medal reads: “In the glorious luxuriance of the plants he takes delight,” from a Tang Dynasty poem. The other side of the medal depicts the Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut’s plant expedition of 1570 BC.

Why do you think these cultural references were chosen to decorate the medal?

Diversifying the U.S. Diet

The 500th anniversary of Columbus in the Americas was also in 1992. To mark the occasion, numerous symposia were held on international germplasm transfer. Sperling was invited to address a broad public on this occasion. To prepare, he recorded his meals over a one-year period and determined that he had consumed more than 300 vascular plants. His goal was to illustrate the plant diversity (or lack thereof) represented in the modern American diet. The speech he ultimately gave showed how the American diet could be diversified through the inclusion of crops he had spent his life locating, studying, and cultivating for human benefit.

Glossary of Terms

Germplasm

Genetic resources including seeds, tissues, and/or DNA sequences that are preserved for breeding.

Back to top

Herbarium

A collection of plant specimens, usually dried or pressed, that have been preserved and described for scientific study.

Back to top

Ethnobotany

A discipline devoted to studying the relationship between humans and plants.

Back to top

Cold War

A period of global rivalry between the capitalist Western Bloc and the communist Eastern Bloc from 1947 to 1991.

Back to top

Further Reading

Chacko, Xan Sarah. “When Life Gives You Lemons: Frank Meyer, Authority, and Credit in Early Twentieth-Century Plant Hunting.” History of Science, 56 (2018): 432-469.

Cohen, Joel I., J. T. Williams, D. L. Plucknett and H. Shands. “Ex situ conservation of plant genetic resources: global development and environmental concerns.” Science 253 (1991): 866-872.

Maxted, Nigel, Danny Hunter, and Rodomiro Ortiz Rios. Plant Genetic Conservation. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Sperling, C.R. and D.E. Williams. “Horticultural crop germplasm: 500 years of exchange.” In International Germplasm Transfer: Past and Present. CSSA Special Publication 23 (1995): 47-60.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

DIGITAL EXHIBITIONS

Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Poisonous Plants

Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories from 1887 to 1927 open a window to the history of medicine and empire.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Sesame Plots

Diaspora in twenty-one openings.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Forests of the Future

Modern agricultural practices are unsustainable. Is tree farming the answer?