Donald F. Othmer

Perhaps best known for inventing the Othmer still and coediting the ‘Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology,’ Othmer was also an educator, an entrepreneur, and a philanthropist.

Early in his career as a chemical engineer, Donald F. Othmer found greater economic stability in academe than in industry, but in the long term he benefited from his connections with industry, as inventor and as investor.

Othmer held more than 150 U.S. and foreign patents, most of which he obtained while working as a full-time professor at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn (now the Polytechnic Institute of New York University).

Chemical Engineering and the Othmer Still

While still in high school Donald Othmer (1904–1995) was alerted by his solid geometry and chemistry teachers to the then new field of chemical engineering. From Central High School in Omaha, Nebraska, he went to the Armour Institute in Chicago (now the Illinois Institute of Technology), the University of Nebraska, and the University of Michigan.

With a doctorate in chemical engineering from Michigan in hand, he went to work for Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York, which was then converting to the production of “safety” film—cellulose acetate—instead of the dangerously explosive cellulose nitrate.

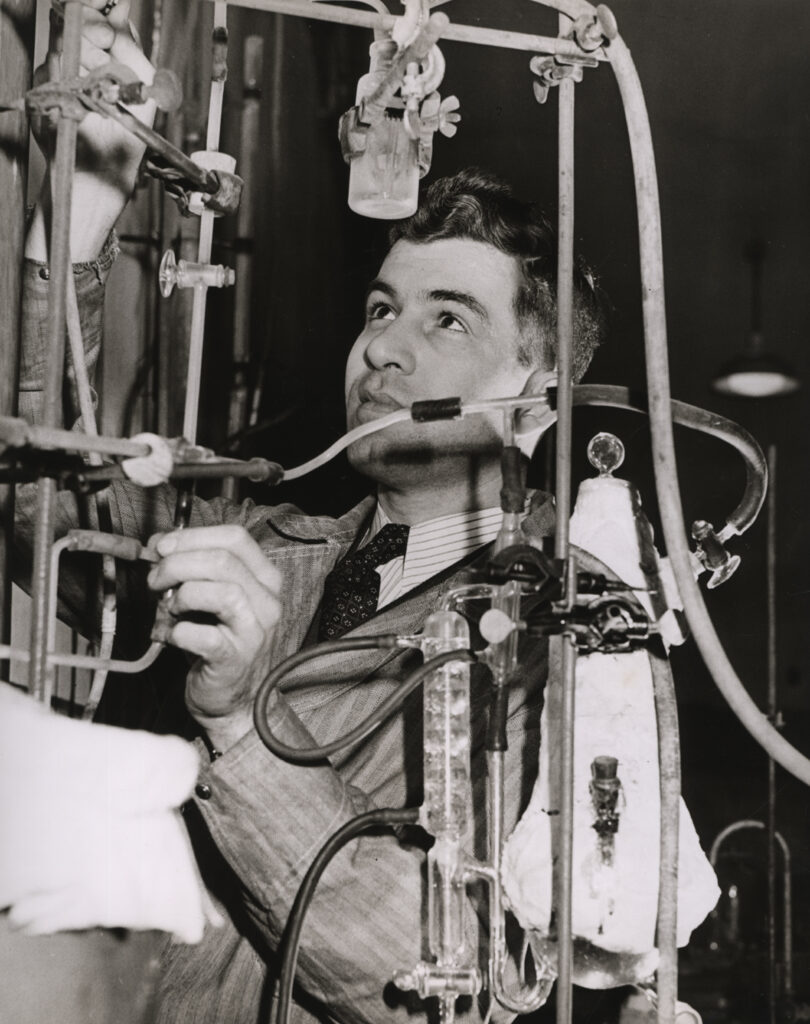

While working out the problems of acetic acid recovery from the acetate-making process, Othmer invented a basic laboratory device, the “Othmer still,” for the simple and precise determination of vapor-liquid equilibrium data. Known for his hands-on approach, he learned to blow glass so that he could build the still himself. Today it is used in industry worldwide and is also commonly found in physical-chemistry teaching laboratories.

When the Depression forced a slowdown in Kodak’s expansion, Othmer decided to run his own business as an independent consultant, until lean economic times made selling patent rights an increasingly problematic activity.

LEARN MORE

Biography is one way of learning about a person. Oral history is another. Spend a few minutes listening to Donald Othmer’s interview archived by the Science History Institute’s Center for Oral History. What do you hear? Has the recording picked up background noises, interesting accents, nervous laughter, or meaningful pauses? What might these tell you about the interview context, who is speaking, or how the speakers feel about the memories being discussed? What do think you can learn about Othmer from his oral history that is different from the content of this biography?

Donald Othmer, with a gold-plated Othmer still in the background.

Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, Other Projects, and Recognition

In 1932 Othmer joined Brooklyn Polytechnic as a professor of chemical engineering, a position that provided him economic stability. There he collaborated on the Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology with Raymond Kirk, a colleague in the chemistry department. The encyclopedia is, in the words of the New York Times, “as well known to generations of chemical engineers as Hoyle is to card players.”

Othmer continued to devise process innovations and patent them, commonly following up topics introduced by his students, who were often already working in the chemical industry but taking classes in the evenings or on weekends to complete academic degrees.

Othmer’s patents cover methods, processes, and equipment for the manufacture and processing of chemicals, solvents, synthetic fibers, acetic acid, and methanol. He long advocated using methanol as a fuel for motor vehicles because it contains fewer pollutants and in the long run is more plentiful than gasoline.

Other projects included providing potable water through desalinization plants and improving the processing of domestic and industrial sewage. Vacations and summers found Othmer traveling worldwide to advise on the installation of his various patented processes.

Othmer was the recipient of both the Founders Award of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers and the Society of Chemical Industry’s Perkin Medal.

Philanthropic Endeavors

Donald and his wife, Mildred Topp Othmer, were generous philanthropists during their lifetimes, but their most substantial gifts came after their deaths in the mid-1990s.

To the surprise of nearly everyone who knew them (the Othmers were well known for their staunch frugality), their estate was worth hundreds of millions—the result largely of wise investments managed by the famed investor Warren Buffett, a fellow Omaha native.

Their gifts went to support medical care facilities and institutions devoted to chemistry and chemical engineering, including the Chemical Heritage Foundation (CHF), now the Science History Institute.

In 1988 they launched a challenge grant to establish the Donald F. and Mildred Topp Othmer Library of Chemical History at CHF, and the Othmer Gold Medal, named for Donald, is given to outstanding individuals who have made multifaceted contributions to chemical and scientific heritage.