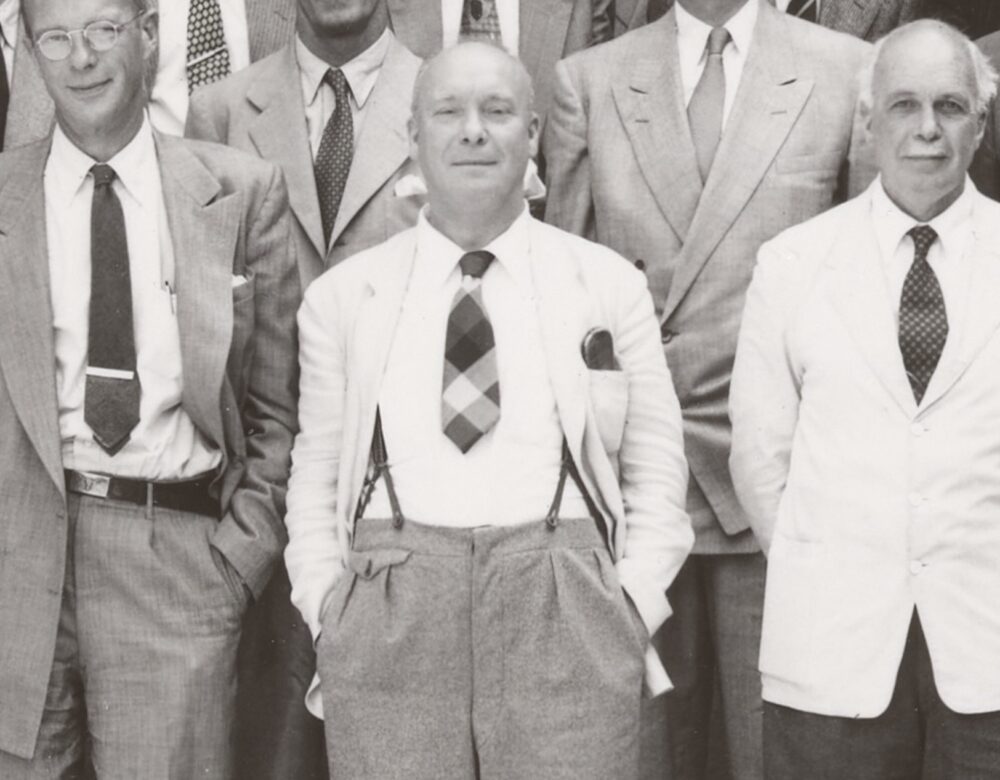

William Astbury

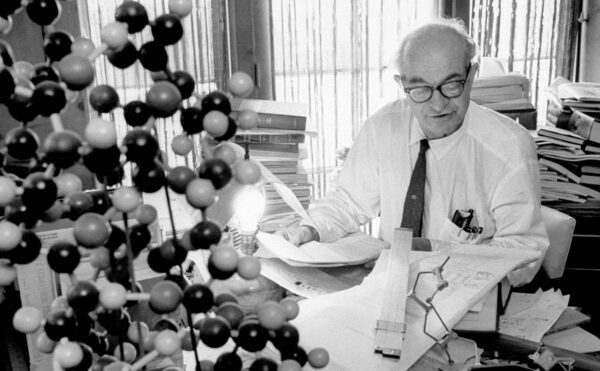

A pioneer in the field of molecular biology, Astbury used X-ray crystallography to study molecular structures within living organisms.

Wool fibers might not seem like the stuff of cutting-edge science. But thanks to textile physicist William Astbury (1898–1961), the study of wool spurred new developments in the life sciences during the first half of the 1900s. Astbury’s pioneering use of X-ray methods to reveal the molecular structure of wool led to the first attempts to identify the structure of the substance that became known as DNA.

From Longton to London

Astbury grew up in Longton in a central region of the U.K. known as “the potteries.” It was a place made famous by novelist Arnold Bennett (1867–1931), who described “an architecture of ovens and chimneys…its atmosphere is as black as mud; for…it burns and smokes all night.” Like some of the characters in Bennett’s novels, Astbury sought to escape.

LEARN MORE

Read Bennett’s vivid description of the region where Astbury grew up. How do you think literature relates to the study of history? Do you think biographies of scientists should begin in childhood or not, and why?

Astbury succeeded thanks to his mother who from an early age had inspired him with her own insatiable curiosity and love of learning. This led him to study natural sciences at Jesus College, University of Cambridge. Astbury arrived in Cambridge in 1917, but after only two terms was summoned for military service in the Royal Army Medical Corps where he first encountered X-ray technology. This, in time, would bring him international renown.

X-rays had first been discovered by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, and the military had been quick to seize upon their power as a tool for medical investigation. But when World War I came to an end, Astbury completed his university studies and learned that X-rays could reveal much more than the fractures in bones.

Astbury came to this realization when he joined the London-based research team of physicist William Henry Bragg (1862–1942) in 1919. A few years earlier, while Bragg had been a professor at Leeds in the North of England, he and his son Lawrence had made an important discovery. They found that the patterns made by X-rays when they were scattered by a crystal allowed one to calculate the precise arrangement of atoms and molecules in that crystal. Using this method, which they named X-ray crystallography, the Braggs successfully identified the atomic structure of inorganic materials such as ice and common salt. Building on this work, Astbury considered a more challenging question: could X-ray crystallography reveal anything about the makeup of living organisms?

“The Most Exciting Protein in the World”

Among candidate materials, Bragg’s group was most interested in wool. It was one of the main raw materials for the British textile industry and therefore of great economic importance to the nation. But concerns had been growing since the late-1800s that British industry might lose its competitive edge to foreign rivals—particularly German companies, which excelled in applying basic science to industrial problems.

Recognizing the need to address this challenge, Bragg urged the textiles department at Leeds, the biggest department of its kind in the country, to appoint “a keen young man” who could pioneer the application of physical methods like X-ray crystallography to the molecular structure of wool. The hope was that this would lead to improvements with respect to wool’s water retention and elasticity, among other properties.

This is how Astbury became the first lecturer in textile physics at the University of Leeds in 1928. His position was made possible by a donation from the Clothworkers Company of London. Initially at least, Astbury did not share his mentor’s enthusiasm for the move—wool fibers seemed to him like a rather dull subject. But he soon realized that the implications of this work went way beyond the textiles industry, and he ended up praising wool as “the most exciting protein in the world.”

“A Molecular Centipede”

The wool proteins that Astbury studied were insoluble fibers that served a structural role. But this is just one of many roles that proteins can play. Some operate as enzymes; others function as chemical messengers; or they might transmit the flow of electrical signals through the body. Proteins, in other words, are powerful little biochemical machines.

In the late 1920s, the molecular structure of these tiny machines was still a mystery. But Astbury’s X-ray studies of wool, taken using a handmade camera, offered a vital clue. Some scientists had predicted that proteins might be huge molecular chains (or “polymers”) formed by joining together smaller molecules known as amino acids. Astbury’s X-ray images of keratin showed that this was indeed the case. In this respect, keratin looked rather like beads strung together to form a necklace or, as he described it, “a molecular centipede.”

Moreover, Astbury found that the amino acid chains of the keratin proteins could adopt either an elongated or a compacted form. This not only explained why wool could be stretched, it suggested to Astbury that the general function of proteins might lie in the shapes adopted by their molecular chains.

“A Remarkable Discovery”

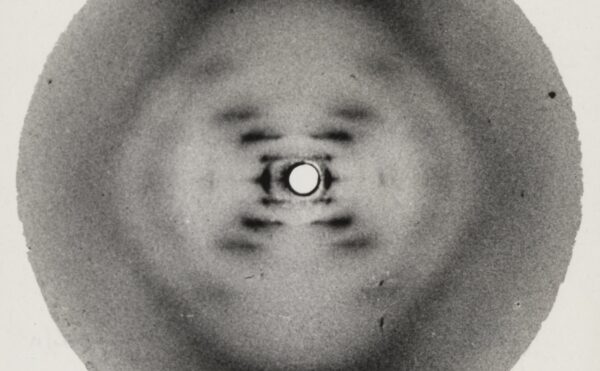

Proteins weren’t the only type of biological fiber that interested Astbury. In 1938, his PhD student Florence Bell demonstrated that the X-ray methods Astbury had pioneered for the study of wool fibers could be used to reveal the regular, ordered structure of “thymonucleic acid,” which later became known as DNA. In so doing, she laid the foundations for the later work of British chemist Rosalind Franklin. In a magazine article from 1954, molecular biologist Francis Crick himself credited Astbury and Bell as having pioneered the use of X-rays to study the structure of DNA.

Bell was unable to continue her work on DNA after she was summoned for military service in 1941. But DNA research continued in Astbury’s lab despite her absence. In 1951, another member of Astbury’s research team, Elwyn Beighton, took some new X-ray images of DNA. These look very much like Photo 51, which was one of several clues that led to the identification of the double helix in 1953.

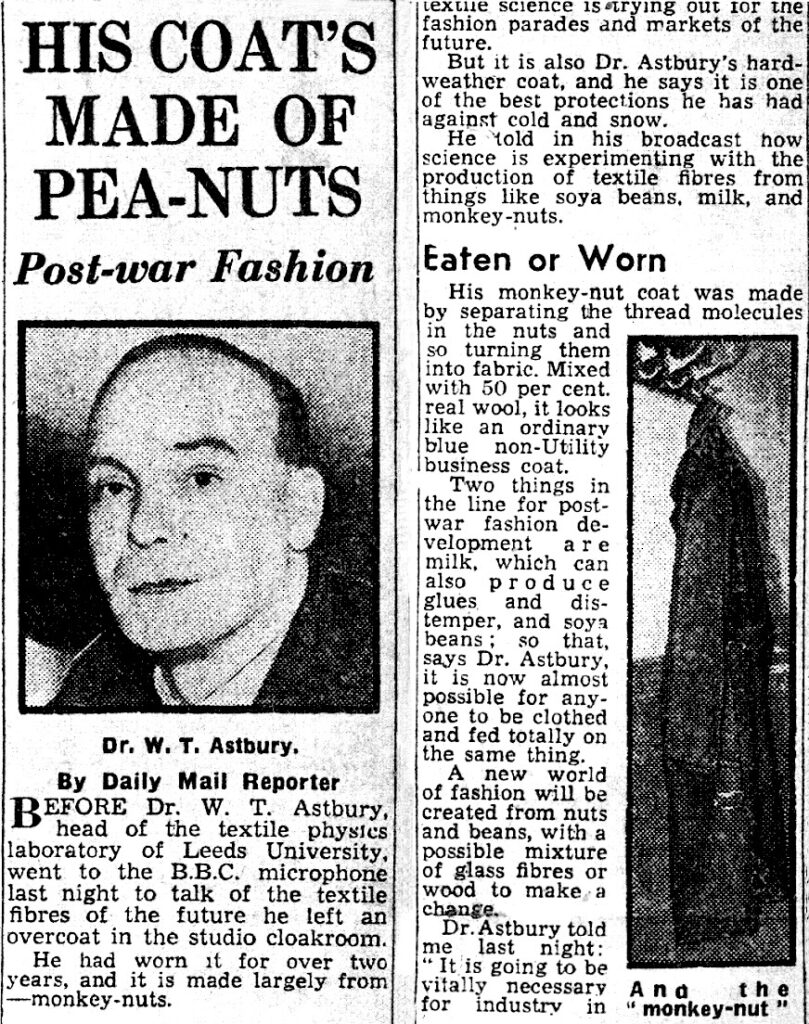

DNA never became the sole focus of Astbury’s work. His larger interest was in how the 3D molecular shape of biological materials gives rise to the ways they behave. There was no better example of this than his rather unusual overcoat, which caught the eye of the national newspapers.

“His Coat’s Made of Pea-Nuts”

Astbury’s coat, along with a jumper worn by his daughter Maureen, was woven from Ardil—a material made by using a chemical treatment to refold the molecular shape of peanut proteins into insoluble fibers. This new textile fiber was produced at a pilot plant in Ardeer, Scotland, by the British chemical company ICI, and it was based on work done by Astbury with collaborators at Imperial College, London. With the price of wool being relatively high at the time, Ardil seemed to offer a cheap and abundant alternative for the textile industry. But with a fall in the price of wool and complications in the supply of peanuts, it became less attractive. In 1957 ICI ceased its production.

The Ardil fiber was nevertheless a powerful demonstration that protein structures could be deliberately engineered at the molecular level to make useful products. Speaking on a BBC radio broadcast in 1942, Astbury predicted that one day this technology would give rise to entirely new industries. Thanks to contemporary developments in artificial intelligence, his prediction could become a reality.

In 2024, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of Alphafold, a tool that predicts the 3D shape of proteins from their amino acid sequence. Since that time, other AI tools have been developed that allow scientists to design novel protein structures with specific functions. This ongoing revolution has its unlikely and humble origins in Astbury’s X-ray studies of wool fibers and his monkey nut coat.

Glossary of Terms

Enzyme

A kind of protein that can break down and change different types of molecules or ingredients.

Back to top

Polymer

A large molecule made up of small chaining subunits; these can be natural (e.g. DNA, proteins, cellulose) or synthetic (e.g. plastics, nylon, polyester).

Back to top

Keratin

Structural proteins found not only in wool but in things like hair, nails, horn, hoofs, feathers, and skin.

Back to top

Monkey nut

Peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) are called monkey nuts in British English.

Back to top

Further Reading and Listening

Astbury, W. T. 1955. “In Praise of Wool.” Proceedings of the International Wool Textiles Research Conference, B, 220–43; p.220.

Hall, Kersten. The Man in the Monkeynut Coat: William Astbury and the Forgotten Story of How Wool Wove a Road to the Double-Helix. Oxford University Press, 2014/2022.

“The Astbury X-ray Camera: From Dark Satanic Mills to DNA,” Centre for History and Philosophy of Science, University of Leeds.

“The Man in the Monkey Nut Coat: How a 1940s Scientist Made ‘Vegan Wool’ from Peanuts,” The Conversation, April 5, 2023.

“The Man Who Almost Discovered the Double-Helix,” BBC History Extra, March 23, 2023.

Perspectives on Science Technology and Medicine, DNA Papers Episode 6: William Astbury, Florence Bell and the First X-ray Pictures of DNA.

Thomas, John Meurig. “The Birth of X-Ray Crystallography.” Nature 491, no. 7423 (November 2012): 186-87.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Linus Pauling’s Vitamin C Crusade

The path to a dubious cure.

COLLECTIONS

History of Molecular Biology Collection

This archive documents the foundation of molecular biology and the race to describe the structure of DNA.

DISTILLATIONS PODCAST

Science, Interrupted

The story of the 1975 Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA.