John James Audubon is well known now, but back in the early 19th century, he was an ambitious “nobody” who dreamed of packaging his wildlife paintings together into a book. After several heartbreaking setbacks, his career was in ruins—until he hatched a desperate plan to win new patrons. It involved a rare American eagle, the Bird of Washington. The gamble paid off, making Audubon the most famous ornithologist in history.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

After two empty years of searching, the appearance of the eagle startled John James Audubon.

Audubon was strolling along a road in Kentucky, to visit a friend. A hundred yards ahead sat a pen where the friend slaughtered hogs and dumped their organs. You can imagine how pungent it smelled.

Suddenly, Audubon heard wings fluttering. An eagle who’d been snacking on hog guts shot up from the pen and perched on a branch overhead. Audubon could barely believe his eyes. This was not a bald eagle. It was the Bird of Washington—a far rarer species.

Audubon had glimpsed the bird just twice before. The second time, he’d spied a nest on a cliff with two parents and two chicks. He’d tried to shoot one to collect it, but a sudden storm had thwarted him.

Now he had another chance. Quietly, he withdrew a rifle from his pack and crept forward.

He later swore that the eagle saw him approach—and stared right back at him, undaunted. Audubon raised his rifle, stilled his breath, and fired.

The bird was dead before it hit the ground. Audubon raced up, giddy. The eagle was beautiful, with a ten-foot wingspan. And while he had no way of knowing it, this specimen would prove to be the most important one he ever collected. It would salvage his career at its darkest moment, and win him international fame.

In fact, without the Bird of Washington, no one today would know who John James Audubon—the most famous naturalist in American history—even was.

According to his autobiography, Audubon was born in New Orleans in 1785, the son of a sea captain. He spent his childhood in France. There, he picked up painting, and trained under the famous French artist Jacques-Louis David.

When Audubon was 18, his father summoned him back to America to manage a family plantation near Philadelphia. Audubon quickly ran it into the ground. He had no mind for business.

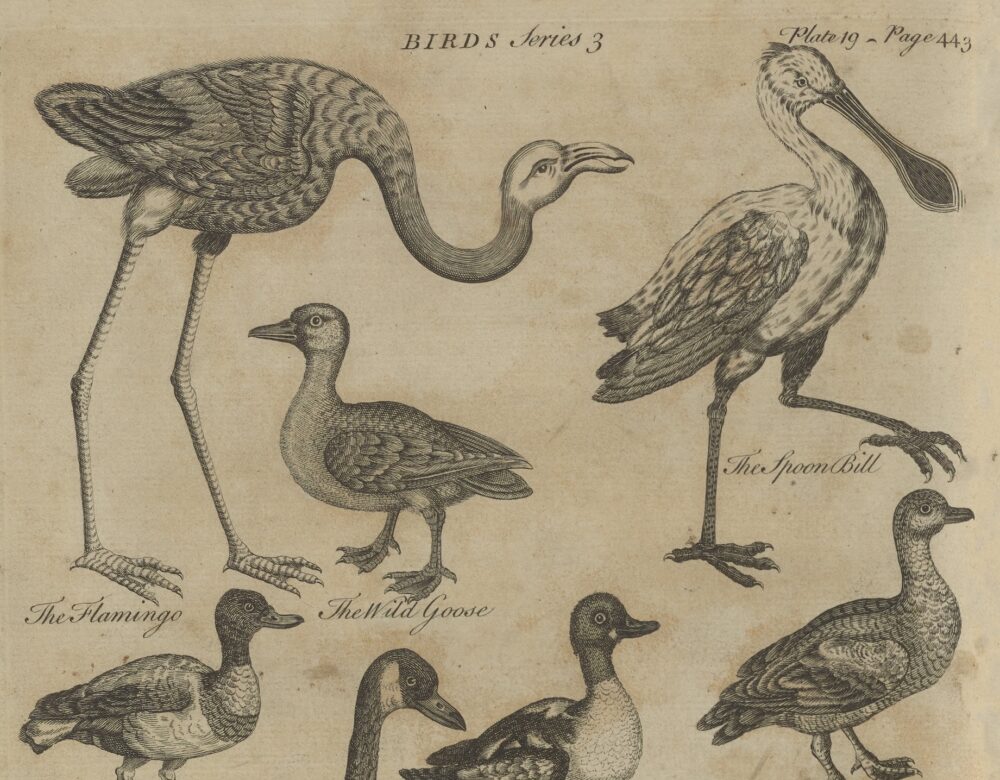

Instead, he spent his days tramping about the woods, looking for birds. He was obsessed with them. Songbirds, hawks, waterfowl—anything with feathers fascinated him.

So much so, that he had to possess them. It’s a paradox, but the great bird-lover Audubon was also a prolific bird-killer. He shot thousands of them.

Afterward, he’d usually sketch the bird, then eat it. If he was out in the woods, he roasted them over a fire—sometimes with a sprinkling of gunpowder for seasoning. Other birds he brought home to make bizarre dishes: blackbird potpie, owl gumbo, sautéed flamingo tongue.

With his best specimens, Audubon painted them, usually in watercolors. He’d hang them from wires or pin them to a board in a lifelike position. It could take days before he finished. Sometimes the birds started rotting. But Audubon kept painting until he was satisfied.

Still, Audubon longed to be more than an artist. He wanted to make his name as a scientist, too. And in 1804, he came up with his first experiment.

It involved the peewee flycatcher, also known as the Eastern Phoebe. It’s a tiny, plump bird with a white chest and grey body. It looks like it has a sunflower seed for a bill.

Audubon was trudging along a creek one spring day when he came across a cave. Inside, he found a peewee flycatcher nest with five chicks.

A question occurred to him. That coming winter, the birds would migrate south, then return to Pennsylvania the next spring to mate. But where exactly would they return? To this creek? Even this cave? Or would they go somewhere else?

This habit of returning to your birth home to breed is called natal philopatry. It’s common in salmon and sea turtles. But does it happen with birds?

Audubon devised a way to test this. He snuck up to the flycatcher nest and tied a silver thread to the leg of each chick. He could then return next spring. If he found any flycatchers with silver threads, that meant the original birds had returned. This type of study—where you catch, band, release, and track animals—is now standard in ecology, thanks to Audubon.

To be sure, his experiment did not go smoothly. The wily flycatchers kept unknotting his threads and dumping them. But they eventually got used to them and stopped bothering.

Six months later, the trees erupted in gold and red. The flycatchers took off south. Audubon spent an anxious winter waiting. He hurried back to the cave as soon as the weather allowed.

Lo and behold, he found two flycatchers nearby with silver threads—40 percent had returned. It was a thrilling discovery for the teenager. Smart, original research.

Except, it was probably wrong. According to Audubon’s own account, he personally observed the return of the banded flycatchers in spring 1805. More specifically, another local birder recorded the flycatchers returning on March 7th.

But according to historical documents, Audubon actually left home to visit France on February 28th—a week earlier. He wasn’t even in Pennsylvania when the birds returned. He could not have personally observed anything.

Now, perhaps someone else noticed the banded flycatchers and told Audubon about them. And maybe in writing the results up, Audubon inserted himself into the story for simplicity’s sake. Scientific standards were looser then.

Except, there’s another problem. Later scientists repeated the experiment with larger sample sizes, nearly 12,000 peewee flycatchers. And in this work, less than 2 percent returned to within even a hundred square miles of their birth home. In fact, no study of any related bird has ever recorded rates over 14 percent.

Audubon’s 40 percent therefore seems suspiciously high. And given that Audubon wasn’t even in the country then, you can’t help but wonder whether Audubon just made the results up.

It’s an uncomfortable thought. Audubon is an American icon. And his story about inventing the practice of bird-banding is a founding story of American ornithology. The tale still gets repeated today. But it’s probably total bunk.

The few biographers who’ve noticed the problems with Audubon’s account have explained it away as a forgivable lapse—a young man who simply got too eager, too ambitious. But it’s not the last time Audubon would run into trouble.

In 1808, Audubon moved to Kentucky. Before long, he devised another ambitious idea. He wanted to package all his wildlife paintings into a book. He would call it Birds of America.

It would be like nothing else in science. He wanted to render each bird life-sized, even vultures and turkeys. The book would therefore need to be humungous, which would also make it expensive. To finance it, he would need subscribers to pay for installments before the book was even finished—a risky request.

And the more he thought about it, the more doubts began creeping in. Would anyone subscribe? After all, he was just a bumpkin in Kentucky. He also felt self-conscious about his command of English, which was his second language behind French. Could he really pull off such an ambitious book?

The person who finally convinced him to try was, of all people, the nephew of Napoleon. Lucien Bonaparte was a noted ornithologist. In 1824, he was living in Philadelphia, the center of American science then.

Audubon happened to be visiting Philadelphia himself at the time. As two French-speakers obsessed with birds, they naturally hit it off. And when Audubon mentioned his book project, Bonaparte was smitten. He begged Audubon to pursue it.

But when Audubon finally worked up the courage to approach some naturalists in Philadelphia, things went south quickly. All due to the machinations of one man: the hated George Ord.

Biographies of Audubon are always harsh on Ord. One called him a “long-faced, quarrelsome, wealthy … dilettante.” The odium just drips off the page.

Ord was tall and stoop-shouldered, with swirls of white in his black hair. As the son of a prosperous rope merchant in Philadelphia, he had plenty of money to pursue science. He worked on the specimens that Lewis and Clark hauled back from the Louisiana Territory, and he provided the first scientific description of grizzly bears and pronghorns.

But Ord’s passion was birds. Initially, he collaborated with his mentor, the ornithologist Alexander Wilson. After Wilson died of dysentery in 1813, Ord completed a book that Wilson had started—a book on American birds.

You can see the problem. Ord had published a book on birds, a book he had a financial interest in. Then Audubon shows up in Philadelphia with his gorgeous paintings and announces plans to publish an even bigger and better book. It’s not hard to imagine Ord feeling threatened.

Audubon wanted the prestigious Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia to publish his book. Ord happened to be vice-president of the Academy. Not surprisingly, the Academy rejected Audubon’s book.

And more humiliation was in store. A few Academy members had been wowed by Audubon’s watercolors. So they nominated him for membership in July 1824. The full body of members voted on the matter in August. They did so by secret ballot—dropping into a container either a white marble for yes or a black marble for no.

I’ll save you the suspense. The Academy black-balled Audubon. The message was clear: You’re not welcome here.

The rejection crushed Audubon. He loved America and thought of his book in patriotic terms. It would demonstrate the scientific and artistic might of the young republic. But American science had rejected him. And with no hope of publishing at home, he decided to try England.

This was not an easy decision. The thought of leaving America was emotionally wrenching. Audubon also had little money. He would have to leave behind his wife and children to fend for themselves—all for a venture that might flop. He might even get stuck abroad, unable to return.

But he felt he had no choice, no other outlet for his ambition. It was England or bust.

Audubon arrived in England with his portfolio of paintings in July 1826. And initially things went well. Within two weeks, he staged an exhibition in Liverpool. Four hundred people crowded in. They marveled at how lifelike his birds looked. Another exhibition followed in Edinburgh.

Beyond his paintings, people were equally enamored with Audubon as a person—partly because he played up his backwoods persona. He kept his hair long and wild. He wore a wolfskin coat. At dinner parties, he imitated gobbling turkeys and hooting owls. He told stories about hunting racoons and holding barbecues on the 4th of July. People lapped it up.

Given the splash he made, Audubon secured a publisher straightaway, along with an engraver. The engraver performed the critical task of translating Audubon’s detailed paintings onto metal plates for printing the book’s pages.

Before long, Audubon’s dream was coming together. After his struggles in America, he could hardly believe it.

Then disaster struck. After just ten metal plates, his engraver quit.

Why isn’t clear. The engraver cited a strike among his colorists, the men who added paint to the plates for printing. But some historians suspect other reasons. Despite the splash he made, Audubon still hadn’t secured many subscribers for his expensive book. So perhaps the engraver realized that he was toiling away on a burdensome, time-consuming project that might end up flopping financially. The strike might have been a convenient excuse to cut bait.

Once again, Audubon faced ruin. But also once again, Napoleon’s nephew saved him.

Audubon was in London when the engraver quit. So was Lucien Bonaparte. After hearing of his friend’s plight, Bonaparte introduced Audubon to members of the influential Royal Society scientific club.

Audubon no doubt arrived nervous. Perhaps he donned his wolfskin jacket; or perhaps a somber suit better fit the occasion. Regardless, Audubon spread his paintings out, bit his knuckles, and anxiously studied the faces of the scientists while they studied his work.

To his immense relief, they adored the paintings. Especially one piece—the Bird of Washington, the majestic eagle he’d shot a decade earlier near the pen full of hog guts.

The Bird of Washington resembled a bald eagle, except without any white on its head or tail. Its lower bill was also longer, and the skull flatter. Most significantly, the Bird of Washington was 25 percent larger.

Audubon’s painting shows the bird perched on a crag. Its claws look powerful enough to crush the rock they’re gripping. Its dark brown wings are crossed behind its back. And just like how the bird had stared down Audubon before he shot it, this one eyes the viewer in profile, its chest thrust out like a soldier’s.

After watching the Royal Society members gape at the eagle, Audubon made a fateful decision. Given his success at the Society, a new engraver stepped forward. And the first bird Audubon ordered him to engrave was the Bird of Washington.

This choice was crucial. Audubon knew that if he didn’t secure more subscribers, fast, his dream project would fall apart. He therefore needed a magnificent set of prints to entice people. And the Bird of Washington would be the centerpiece of this set. He was gambling his whole future on this eagle.

And the gamble paid off. Over the next few months, a few crucial patrons stepped forward—including King George himself. Talk about an endorsement.

There’s no record of why exactly the eagle appealed to them, but historians have made suggestions. In the European mind then, America was a vast wild frontier. And the idea of a giant eagle lurking there must have thrilled them.

The bird’s name helped as well. Audubon named it the Bird of Washington after George Washington. And he did so only after arriving in England—a calculated decision.

The United States had recently fought two wars with Great Britain. And somehow, the upstart republic had gone toe to toe, blow for blow, with the greatest military power in the world. Britain might have whipped Napoleon, but not George Washington. The name commanded respect there. Combine that with the beauty of the painting itself, and the English couldn’t help but marvel at it.

Meanwhile, the Royal Society gave Audubon the chance to write an essay for its zoological journal. In it, Audubon described the years of frustration he’d endured tracking down this ten-foot-wide bird. How he first saw it soaring overhead on a barge on the Mississippi River. Then, how he missed his chance to shoot one a few years later, due to a storm. He finally bagged one near the pig-slaughtering shed while walking the forest in Kentucky.

This essay marked the first new species Audubon ever described. In addition, a review of Audubon’s work appeared alongside the essay. It was written by a revered British ornithologist named William Swainson, and Swainson was rapturous. He wrote, “I have long aimed at that perfection which M[r]. Audubon has so fully attained.” He also called Audubon a genius and begged others to subscribe.

In truth, this review wasn’t quite on the up and up. In exchange for writing it, Audubon promised Swainson a copy of his Birds of America at a steep discount, meaning Audubon essentially bribed him. But the review worked: subscriptions poured in. At last, Audubon’s success was assured.

But what Audubon did not tell the ornithologist—what he didn’t tell anyone—was that he’d invented the Bird of Washington. As we’ll hear next week, the whole saga was an elaborate fraud.