John James Audubon always had his detractors, but the public and the scientific community at large loved him. But it turns out his detractors were onto something. The eagle that made Audubon famous, the Bird of Washington, was nothing more than an elaborate lie. Fawning biographers have suppressed this fact for years, but careful historical work has unraveled the Audubon legend, and the Bird of Washington wasn’t his only deceit.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

This Part 2 of a two-part series. If you haven’t listened to Part 1, you should start there.

It’s ironic that John James Audubon’s legendary book, Birds of America, had to take flight abroad, in Europe.

But eventually, scientists in the United States realized just how important the book was. So much so that, in Philadelphia, the Academy of Natural Sciences once again began debating whether to admit Audubon as a member.

He’d already been rejected once, thanks to the machinations of George Ord. But by September 1831, the academy realized it was embarrassing itself by denying Audubon. Ord happened to be absent from that month’s meeting, so the other members voted Audubon in. Equally gratifying, they voted to subscribe to his book. They were now effectively paying him to be a member.

And before long, Audubon’s canonization was under way. He eventually became the most famous ornithologist in history. Even by 1850, a history book named him one of the twelve most illustrious Americans since George Washington.

And it had all started with the iconic Bird of Washington—the bird that stirred so many subscribers’ hearts in England, including the king’s. Even more than the bald eagle, the Bird of Washington became a symbol of America then. People wrote paeans to it. One read, “From every deep grove the birds of America will sing [Audubon’s] name … And the Bird of Washington, from his craggy home … will scream it to the tempests and the stars.”

The only thing was, the Bird of Washington didn’t exist. It never had, outside Audubon’s imagination. And given how it launched his career, it might be the most successful fraud in art and science history.

Birds of America was one of the most expensive books ever printed. Subscribers paid $1000 each. That’s more than $32,000 today, for one book. At 435 pages, that’s roughly $75 per page.

And the book didn’t even come assembled. Subscribers simply got batches of five pages at a time. Each batch had one large species of bird, one medium species, and three small ones. Then they had to sew the 435 pages together themselves, or send everything to a bookbinder at their own expense.

The book cost so much in part because Audubon decided to use so-called double-elephant pages. These were sheets more than three feet tall and two feet wide—the largest paper available then. This allowed Audubon to show birds at life size—even turkeys and flamingos. He could also show them in their natural habitats, with trees and rocks and water around.

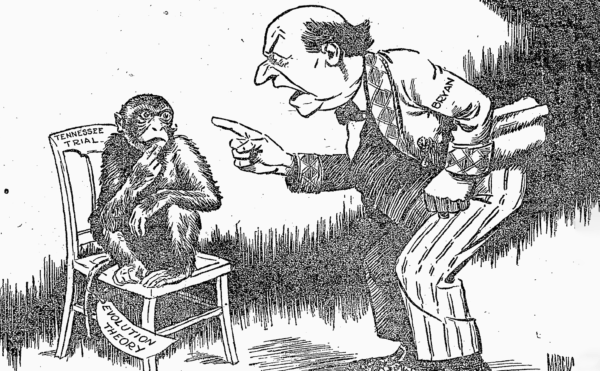

The Bird of Washington appeared on page 11. It was the species that most birders no doubt turned to right away, the one that sent tingles down their spines. What a majestic creature.

Except, when naturalists went looking for it in the wild, no one could find one. To be sure, Audubon had said they’re rare. And country folk did report spying one here and there. But with such a large eagle, you would think one would turn up somewhere.

This lack of specimens actually violated scientific standards then. Before a species counted as new, naturalists had to deposit a specimen in a museum. That way, colleagues could examine it and check the claims for it.

Now, given the difficulty of travel then, Audubon’s supporters in England had let that standard slide originally. They took Audubon’s word that he had a Bird of Washington back in Kentucky and would deposit it at a repository museum in Philadelphia.

But Audubon never did this. That began to worry ornithologists. One was William Swainson, who’d been effectively bribed to write a rapturous review of Audubon’s work, the one that begged others to subscribe.

Swainson feared that he’d let his enthusiasm for Audubon’s art cloud his judgment about Audubon’s science. And even beyond the lack of a specimen, Swainson and colleagues noticed things about Audubon’s claims that didn’t add up.

For one thing, a caption written on the Bird of Washington painting said it was male. But when Audubon had exhibited the piece in Liverpool, the accompanying catalogue said it was female. Was this a simple mistake? Or could he just not keep his story straight?

There was also the sheer improbability of every other ornithologist in America missing this giant bird before Audubon. Swainson realized that the only “proof” the bird existed was Audubon’s painting and a few anecdotes from his friends.

In 1830, a rumor set Swainson’s mind at ease. He heard that someone had finally deposited a specimen of the Washington eagle in Philadelphia. What a relief.

Except Swainson didn’t know the full story. In truth, Audubon had been passing through Philadelphia in 1830. And the rumor came from him.

It began with a bet. In March 1830, Audubon met up with a fellow naturalist near Philadelphia, Richard Harlan. Harlan actually had a bad reputation; he was considered a scoundrel. But he and Audubon got along well enough.

Together, they visited a zoo which had supposedly captured a Bird of Washington. Harlan took one look and was convinced.

But Audubon shook his head. He declared that it was simply an immature bald eagle. It would molt soon and acquire the familiar bald-eagle plumage with a white head. Harlan said no way, so they wagered on the matter. And, Audubon won. The bird soon molted into a normal bald eagle.

Then they heard a rumor about another Bird of Washington. This time, it was in a taxidermy shop. Harlan and Audubon swung by. The specimen left Harlan glum. It looked just like the bird at the zoo—another immature bald eagle.

But to Harlan’s surprise, Audubon contradicted him. He said, That’s a Bird of Washington if I ever saw one. Harlan was thrilled. They’d found a specimen at last!

In reality, Audubon was just being clever. He likely knew the bird was another immature bald eagle. But, being dead, it would never molt and prove him wrong. He also knew Harlan would gab, and spread word about the discovery. And he was right. In fact, Harlan did such a good job gabbing that even Swainson in England heard the rumor.

Unfortunately, Harlan did more than gab. After Audubon left town, Harlan bought the specimen from the taxidermy shop and deposited it with the museum in Philadelphia.

Audubon must have cursed a blue streak. His idiot friend was going to ruin everything! All it would take was one naturalist stopping by to examine it, and he’d be exposed.

And one soon did. His old enemy—George Ord.

Again, Ord had blackballed Audubon at the Academy of Sciences in Philadelphia. Ord had also published a rival book on North American birds—a book that Audubon’s own book blew out of the water. Ord had every reason to resent Audubon.

At the museum, Ord examined the taxidermied Bird of Washington alongside two bona fide bald eagles. He found zero difference between them.

Ord also compared the specimen to Audubon’s painting. There, he found serious discrepancies. Ord saw that Audubon had stretched the lower bill too far in the painting. He’d also made the skull too flat. For an artist of Audubon’s caliber, Ord decided that these could not be simple mistakes. He said Audubon’s painting was, quote, “calculated to mislead.”

Ord finally had it—ammunition to take down his enemy. So did he rush out and publish something? Shout his findings from the rooftops?

No. Audubon was too famous, and Ord feared abuse from his legions of admirers if he said anything. As Ord grumbled in a letter, “I should have a swarm of hornets about my ears, were I to proclaim to the world all that I know of this impudent pretender, and his stupid book.”

Now, that sounds like sour grapes. But historically, Ord was right: the Bird of Washington was a fraud. Audubon’s surviving diaries make this clear.

Recall that the Royal Society asked Audubon to write an essay about shooting the Washington eagle. He’s vague on dates, but it seems to happen in 1819. Yet, in a diary entry from 1820, Audubon admits he has no idea whether the eagle exists. He invented the whole anecdote.

But because Ord stayed mum, the world never found out. As a result, Audubon’s fame just kept growing.

By the late 1800s, ornithologists knew the Bird of Washington didn’t exist. But Audubon was such a hero, that his biographers made excuses. They claimed he’d simply made a mistake, or that the species had gone extinct. That their hero would lie never occurred to them.

Audubon’s painting of the bird has come under fire, too. In 1996, an eagle-eyed historian noticed that Audubon’s bird looked suspiciously like a portrait of a bald eagle published in an earlier encyclopedia. The birds had the same posture—perched on a rock, back to the viewer, wingtips crossed. They both even had the same glint in the upper left corner of their eyes.

In other words, when Audubon told the Royal Society that he had a model back in America for his Bird of Washington painting, he did. It just wasn’t a specimen. He’d ripped off someone’s art, and passed it off as his own.

Indeed, the more historians dig, the worse Audubon looks. His autobiography claimed he hailed from New Orleans, an iconic American city. He didn’t. He was born in what’s now Haiti, the illegitimate son of a sea captain and a maid.

As for his childhood, he did spend it in France. But he never studied under famous painters there. And he’d fled France to avoid military service.

To be fair, he’s certainly not the first person to cover up a lowly birth. But lying in a biography is one thing. Lying in science is another. Recall the experiments he just made up about banding the peewee flycatchers to see if they returned home to mate.

And beyond the Bird of Washington, there are five other species in Birds of America that no biologist has ever seen. Some might be rare hybrids, but others he probably made up. As documented by historians, his rap sheet also includes stealing specimens from museums and ripping off other people’s art on at least six occasions.

Even one of the defining moments of the Audubon legend—getting rejected for membership at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia—hinged on Audubon’s deceptions.

You see, biographers long assumed that Audubon got blackballed there because of cranky, jealous George Ord—someone tearing down an intellectual superior. But that’s not why Ord hated Audubon.

Recall that Ord had a mentor, the ornithologist Alexander Wilson, who died of dysentery. Ord had completed Wilson’s book on American birds. And by all accounts, Wilson was an upstanding gentleman, truly beloved.

But when Audubon arrived in Philadelphia in 1824, seeking to get his book published, for some reason, he started badmouthing Wilson.

Specifically, Audubon spread rumors that Wilson had stayed with him for two weeks in Louisville back in 1810. During that time, Wilson supposedly looked over new species that Audubon had collected. Wilson then published reports of them without Audubon’s consent or any attribution. That made Wilson a thief and a liar.

In reality, Wilson had stayed in Louisville only five days, in a hotel. According to Wilson’s diary, he did look over Audubon’s drawings one morning, then went hunting with him two days later. But he explicitly says they encountered no new species.

It’s not clear why Audubon claimed otherwise. Perhaps he wanted to puff himself up, or win over someone he assumed didn’t like Wilson. Regardless, the ploy backfired. George Ord heard Audubon’s smears. As Wilson’s protegee, Ord had his diaries. And he produced them in public so people could read for themselves that Audubon was lying. That’s why the Academy rejected Audubon’s membership.

And to be clear: so far, I’ve been following the normal historical line on Ord. That he was a nasty, grouchy curmudgeon. And he was. No one ever said he was kind-hearted. But he was a good scientist. And he was right not to trust John James Audubon.

I could go and on about Audubon’s sins. And I have. I’ve put together a bonus episode at patreon.com/disappearingspoon about another experiment that Audubon might have faked. You might have heard the supposed “fact” that birds cannot smell. That’s not true. That canard started with Audubon, a pig carcass, and some vultures.

I’ve also put together a second bonus at Patreon about Audubon tricking another naturalist into publishing fake species. Audubon did so when the man tried to kill a bat with Audubon’s favorite violin. So Audubon took revenge and humiliated him. All that and more at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Audubon died in Manhattan in 1851, at age 65. He had no molars left, and was beset with dementia. But his legend seemed secure, and only grew in later decades. Charles Darwin cited him three times in On the Origin of Species. Multiple species of birds were named after him, as well as the Audubon Society, the world-famous conservation group. There are even cities named for him. In more recent times, he was the subject of a Google doodle. And in December 2010, an original copy of Birds of America sold for $11.5 million.

People continue to love him because he simply had an aura about him—the frontier genius with long hair and a wolfskin coat, a true American original. And we cannot forget the art. It is genuinely brilliant. It still moves people today.

Because of that aura, biographers have twisted themselves inside-out explaining away all the discrepancies and lies they’ve unearthed. They claim he had a “romantic imagination.” Or a Mark Twain–like “frontier sense of humor.” One admirer claimed Audubon had, quote, “no genius for accuracy”—a laughable euphemism.

Only recently have historians seriously challenged his legacy, and chipped away at his status. In addition to his scientific sins, there’s increased scrutiny of his treatment of minorities.

He often relied on Native Americans and Black people to collect specimens or provide information about birds and their behavior. He never credited them. He was hardly alone in that back then, but it doesn’t reflect well.

Worse, he exploited those people in other ways, too. He robbed Native American graves for museum specimens. He also bought, sold, and enslaved Black people, and disparaged the abolition movement as misguided.

As more and more of his sins have come to light, a movement has arisen to strip Audubon of honorifics and rename everything Audubon-related. In fact, dozens of local chapters of the Audubon Society have dropped Audubon’s name—in New York, Philadelphia, Tucson, Chicago.

And as we’ll hear next week, Audubon is not alone in coming under fire. Taxonomy is normally a sleepy field. But there are some nasty fights brewing over who we should, and should not, name species after. Audubon is just one of the many beloved names in the crosshairs.

But as George Ord once said, in defending his mentor Wilson and turning the accusations back on Audubon: “He who resorts to the stiletto can have no reason to complain should its point be reverted to his own chest.”