Taxonomy, the branch of science concerned with classification, has an ugly history of naming species after despicable people. One of the most well-known examples of this is a blind beetle found in the caves of Slovenia and named for Adolf Hitler. Given the controversy these names generate, there have been many calls to drop them. But taxonomists have so far resisted most of these efforts, for reasons both good and bad.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

Around 2002, biologists in Slovenia noticed something strange. They were studying troglobionts, animals that live in caves. And they were finding traps in local caves that had captured a certain beetle.

It’s a pretty ugly bug. It’s tiny and amber-colored, with no eyes. It looks like a termite or a cockroach. Yet people were paying thousands of dollars per specimen. And no matter how many hundreds of traps biologists confiscated, new ones would appear. Poachers pursued this bug as relentlessly as elephants are hunted for ivory and rhinoceroses for their horns.

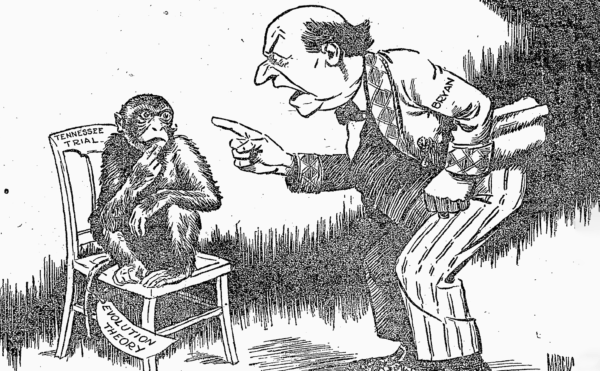

But why? What’s so special about this beetle? Its name. Anophthalmus hitleri. That’s hitleri, as in, Adolf Hitler.

The biologist who discovered it in 1933 named it after Hitler, to celebrate Der Führer’s rise to power in Germany. Now, given that it’s an ugly blind cave bug, that doesn’t seem like much of an honor, but that was his intention.

Nowadays, of course, Hitler’s name is a byword for evil. Except among neo-Nazis. For them, the Hitler beetle is a collector’s item. And relentless poaching has driven this bug to the brink of extinction.

So why haven’t biologists just changed its name? If only things were that simple.

Changing the names of species is a surprisingly fraught topic. So today we’re going to examine this underbelly of biology—and explain why we might be stuck with the Hitler bug for a long time.

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and The Disappearing Spoon, a topsy-turvy science history podcast where footnotes become the real story.

People have always given animals names—racoon, muskrat, Kookaburra. These are sometimes called common names.

But in 1753, biologist Carl Linnaeus introduced a scientific classification system for species. This didn’t eliminate common names, but did give every species a second, official name consisting of a genus and species. Examples include Homo sapiens, Boa constrictor, Tyrannosaurus rex. Linnaeus even named and classified mythological beasts like the phoenix and the hydra.

Some people hated Linnaeus’s system, especially for plants. He talked about their sexual organs in too much detail for those squeamish times. One critic was especially harsh. So, Linnaeus named a weed after him as an insult.

Usually, however, biologists name species after people to honor them. Over 300 species are named for Charles Darwin. Modern examples include a fern named after Lady Gaga; a horsefly named after Beyoncé; a millipede after Taylor Swift; a lichen after Barack Obama. Fictional characters have received honorific names, too: Winnie-the-Pooh, Ichabod Crane, Jeffrey Lebowski, The Godfather, Pippi Longstocking, Popeye, Calvin and Hobbes.

But sometimes names generate controversy. Take the McCown’s longspur, a bird named after John McCown, an American army general born in 1815.

First, it’s not very descriptive. Calling a bird called the Yellow-throated warbler helps you identify it. Calling a bird the McCown’s longspur does not.

Second, McCown was not a biologist and did not describe the bird scientifically. In fact, he only shot “his” longspur accidentally. And obviously he was not the first person to see one. Native Americans knew about them for centuries.

Most importantly, McCown was a bad dude. He deserted the U.S. army for the Confederacy, and he waged genocidal campaigns against Native Americans. Does he really deserve a bird named after him?

Another egregious example is the Englishman George Hibbert, the eponym for a genus of Australian flowers. Again, Hibbert was not a scientist, but a mere patron. And he made his money off the slave trade. Worse, he used his position in Parliament to squash attempts at abolition. And crucially, even people at the time thought his extreme views on the virtues of slavery were disgusting. Yet many pretty flowers still bear his name.

So why keep these names? The big argument is stability. The Latin naming system is the periodic table of biology, and those names appear in records dating back hundreds of years. Abrupt changes would cause countless headaches when searching those records and throw the field into chaos.

Also, consider conservation efforts. Treaties and laws to protect endangered species mention the species by name. If you change the name, it could lose protection. To be sure, you could always go back and change the original law—but good luck getting that through Congress these days.

Another objection to changing names is that political and moral beliefs shift, and one person’s hero can become another’s pariah. Few people today would cry over the erasure of McCown or Hibbert’s name, but what about Gandhi?

I’ll spare your sensibilities, but when he was a young man, Gandhi said some pretty racist things about Black South Africans—to the point that an angry crowd in Ghana tore down a statue of Gandhi in 2018. And there are many species named after Gandhi—spiders, moths, a fossil armadillo. But he remains a hero to billions of people worldwide. So how do we decide whether to strip him of those honors?

There’s also the question of whitewashing history. Take the Hitler beetle. Erase the name and you’re covering up the sin of honoring one of history’s great monsters. I actually think it’s a powerful cautionary tale—about scientists genuflecting shamelessly to power.

Things get even more complicated when you realize some names aren’t meant as honors. There are two species named after Donald Trump. One is a moth with a mop of yellow scales on its head. There’s also an amphibian named after Trump called a caecilian.

Caecilians look like snake-worm hybrids: skinny, slimy, legless critters who wallow in mud. Not flattering for The Donald. But scientists actually named the species after him to draw attention to Trump’s environmental policies, which they fear will drive species like it extinct. Then again, many people love Trump and therefore take offense at such criticism.

Given all this mess, some biologists propose dumping all human eponyms in biology. This sentiment is especially common in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, where there’s a push to restore indigenous names for plants and animals.

Which sounds great—but opens up other cans of worms. Indigenous people are not homogenous. Disagreements and rivalries exist, and they speak different languages. So which name gets priority?

Moreover, some indigenous activists argue that changing species names is, as one writer put it, an “empty gesture meant to assuage liberal guilt.” It does not fix the past, and doesn’t help people now, either. It just makes scientists feel good.

Dumping all human monikers also offends some biologists in formerly colonized countries. They protest that Europeans honored people with names for centuries—and now, suddenly, they’re forbidden from doing the same? They point to the dolphin named after a Native American chief named Tamanend, and a beaked whale named for the Māori whaling expert Ramari Stewart. Can’t those names do good? Humans need heroes, people to look up to.

Still, let’s say we did want to change the names of certain species. Again, the big argument against this is historical stability and the flood of problems that would result. But for all the doomsday talk, many species have undergone name changes recently.

Sometimes it’s a rebranding effort. Fisheries changed the spiny dogfish to the rock salmon, and the Patagonian toothfish to the Chilean sea bass, just to make them sound yummier on menus.

In other cases, names changed for ethical reasons. Apologies in advance, but examples include: the gypsy moth, which is now the Spongy moth; the jewfish, now the Atlantic goliath grouper; and the Oldsquaw, now the Long-tailed duck.

One name that stuck initially was McCown’s longspur. Initially, the American Ornithological Society refused to change it. But in the fallout from the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the Society reversed its position. McCown’s longspur became the more descriptive Thick-billed longspur. Then, in 2023, the Society decided to drop all of the roughly 150 common bird names that included human names.

Reactions were mixed. Many people were overjoyed. They applauded the changes as long overdue. Others grumbled and made “trollish” comments about what bird names would fall next. Were boobies, tits, and pygmy owls now forbidden? Would saying “baldpates” be offensive to people who lack hair?

These complaints often stem from the perception that modern people are projecting their ethics onto the past. And there is truth to that. But even back in 1799, some ornithologists were complaining about naming birds after people. They thought it was silly. So there is historical precedent for opposing human eponyms.

Another criticism of the crusade to eliminate human names involves misplaced priorities. Part of the mission of the American Ornithological Society is conservation—protecting and saving birds. And critics have argued that every hour and dollar spent on renaming birds would be better spent saving bird habitats.

Conservation woes, especially a lack of money, have influenced the naming of other species, too. Recall the caecilian, the worm-snake named after Donald Trump. Unusually, the scientists who discovered it did not name it. Instead, the discoverers auctioned off the naming rights for $25,000, then used the money for conservation.

More wildly, in 2005, a company bid $650,000 to name a monkey in Bolivia. It chose Callicebus aureipalatii. Aureipalatii is Latin for “golden palace.” The winning bid came from the Internet casino GoldenPalace.com.

This infuriated some scientists. One complained about the monkey becoming “a punchline or an advertisement, instead of a reflection of the millions of years of evolution that led to this unique species.” He has a point. Then again, $650,000 can save a lot of monkeys.

Most name changes I’ve mentioned so far have involved the common, everyday names of the animals, not the scientific Latin names. Those names are harder to change because they have to go through international committees.

Being on those committees is pretty overwhelming. There are only a few dozen scientists on each one. Meanwhile, biologists discover around 18,000 new species every year. It is impossible to keep up.

The committees’ work is even tougher due to so-called taxonomic vandals—people who sweep in and name species when they have no right to.

Traditionally, the process for naming a species has required scientists to publish a description of it in Latin in a journal. And the iron-clad Principle of Priority states that the first published name for a species is the official one. Period.

In 2012, taxonomists relaxed some of those requirements. Not the Principle of Priority. But now you can publish the descriptions in English. And you can publish it in e-journals online. Both seemed like good changes—bringing taxonomy up to date.

But vandals saw loopholes. For various reasons, scientists sometimes publish information about a new species without naming it. Maybe genetic evidence shows that it’s there, but they want to write up a more careful description. Or maybe they post the description in a preprint but are still debating an official name and save that for the final paper.

Vandals take advantage of such situations. They rush something into print and propose their own names. A few have even founded their own vanity journals online—just to publish names for species that other scientists discovered.

One reptile expert in Australia has named something like 1800 species using such tricks, close to 200 per year sometimes. He named a few species after his dogs. He also named a frog after a “dunnyseat”—Aussie slang for a toilet lid. Har har. But because he published those names first, by the ironclad Principle of Priority, those officially became the species’ names.

This ungentlemanly behavior enraged other scientists. So much so that some refuse to use the official species names, even in technical publications. Instead, they use names proposed by the actual discoverers. And understandably so.

But that brings up a question. Are the names really so sacred, if scientists can just ignore them? It undermines the arguments for keeping names intact.

And that’s not the only time names have changed. DNA testing has rewritten loads of taxonomic trees and forced many name changes. Or consider the case of the so-called common side-blotched lizard. It lives in the American West and has mating habits like something out of Lewis Carroll.

The female side-blotched lizard has a yellow throat. The males have either orange, blue, or yellow throats. And for some reason, those colors correlate with different levels of aggression in males.

Orange-throats are highly aggressive. They keep a harem of multiple females over a large area and attack any other males who approach.

Blue-throats are moderately aggressive. They usually mate with one female. Sometimes they challenge the orange-throats for another female—only to get the snot beaten out of them. Other times, the oranges just steal the blues’ females. Evolutionarily, then, oranges have an advantage over blues.

Meanwhile, the yellows are wimpy. If they challenge even the middle-aggressive blue-throats, they lose. So evolutionarily, blues have an advantage over yellows.

But yellows have other tricks up their sleeves. Remember, oranges have a harem of many females—often too many to guard. And yellow-throats look like females anyway. So instead of challenging the aggressive orange-throats, yellow-throats sneak in and mate on the sly. That means yellows have an advantage over oranges.

In summary, orange beats blue—blue beats yellow—and yellow beats orange. It’s evolutionary paper-rock-scissors.

Now, however interesting that is, you can imagine why it took scientists quite a while to sort everything out and determine that there’s just one species here. Even messier, sometimes yellow males morph into blues if there are no blues around. And along the way, the lizard had a whole slew of different Latin names—it’s changed nearly a dozen times. So again, names can change without the whole science of taxonomy falling apart.

I admit that these arguments about name-changes give me whiplash. I’ll read one thing and be convinced we should never change names—then read something else and favor it.

I feel especially sheepish when I realize that animals probably don’t care what labels we use. I’ve heard arguments that a bad name, quote, “dishonors the organism”—as if they’ll be challenging us to a duel at dawn.

Still, names do matter to people. Both in who we honor or insult, and in how much we care about a species.

Consider this study from the London Zoo. Scientists there showed pictures of animals to visitors without telling them the animals’ names. The scientists then asked how much people would spend to save the species.

After that, the scientists showed the pictures to different visitors and asked them how much they’d spend. But this time, they also supplied the species’ names. That made a big difference. People spent very little to save the Strawberry Poison Frog. But the Diana monkey, named after Princess Di, was suddenly everyone’s darling.

And to me, that’s the best argument for changing at least some names. Biodiversity hotspots nowadays have huge numbers of endangered species. Unfortunately, these lands were often colonized by Europeans, so few of those species are named after local people. But the zoo study implies that a simple name switch could really boost conservation efforts.

All too often, the debate over changing names devolves into scolding or shaming. But we can also look at the good that can result. We can bring more people into science and get them to care more about the most important thing—saving plants and animals. Changing names might be a hassle. But it’s also an opportunity.