The Ig Nobel Prize is the bizarro cousin of the Nobel Prize. Created in 1991 to promote a satirical science journal, the awards celebrate odd or unusual research that “makes people laugh, then think.” Reception in the scientific community has been mixed—some hate the awards and refuse to accept them, claiming they belittle scientific work. Others have glided proudly onto the stage to accept the honor. Despite the controversy, the Ig Nobels have grown into a beloved institution—and one with some surprising benefits to science.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

When she got the call about the prize she had won, Eleanor Maguire was almost offended.

The year was 2000. Maguire was a neuroscientist who’d recently published an interesting paper. Maybe you’re heard about it.

In London, cab drivers have to pass a grueling exam to get a license. It tests their knowledge of every single road in the city—every crooked lane, every obscure byway, every paved-over cow path dating back hundreds of years. Twenty-five thousand streets.

Maguire wondered if this changed the drivers’ brains somehow—particularly the hippocampus, a place associated with memory. So she scanned the cabbies’ brains, and sure enough—their hippocampi were far larger than normal. Like they were on steroids. It was a fascinating discovery. And, as Maguire found out that day in 2000, it won her a prize.

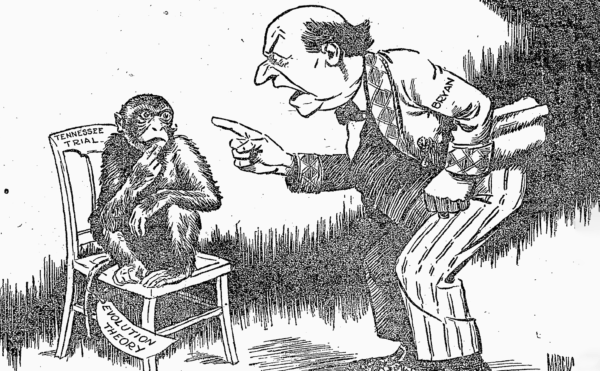

But it seemed more like a booby prize. The award was called the Ig Nobel Prize, a cheeky reference to the regular Nobels. As its motto says, the goal of the Ig Nobel Prize is to highlight research that first makes you laugh, then makes you think.

It’s somewhat controversial. Although it focuses on the absurd side of science, it often touches on surprisingly important topics. But it also sometimes touches a nerve with winners. Not everyone appreciates the joke.

So today, we’re going to explore the Ig Nobels, and what makes them unique. Ultimately, Eleanor Maguire turned down her prize in 2000. But over the years, the Ig Nobels have become a fixture in the scientific community, a bizarro counterpart of the sometimes stuffy Nobel Prize. And along the way, the Ig Nobels have even earned the last thing their founder ever expected—a modicum of respect.

One Friday night in 1997, Andre Geim decided to have some fun. He was a physicist in Holland, and he was building an extremely powerful magnet in his lab.

It consisted of a whole bunch of equipment, but the magnetic force was concentrated inside a coil of wire called a solenoid. At its peak, the force reached 16 tesla. That’s 300,000 times greater than the Earth’s magnetic field. It was crazy-strong.

So strong that it could levitate water. Geim put a drop inside the solenoid and it floated there. Pretty trippy stuff—making water hover.

Then Geim decided to push the envelope. He knew that living things are mostly water. Would they float?

They did. He got a leaf to float. Also a cricket. But one stunt above all captivated people. He grabbed a tiny amphibian, an inch long, and put it inside the solenoid. Presto—a levitating frog.

You can probably see where this is going. Geim published the results, and a few years later, the phone rang—offering him the Ig Nobel prize.

The caller was Marc Abrahams, an American software programmer in his mid-40s with a puckish side. He liked to write spoof stories about math and science. A decade earlier, he’d reached out to Martin Gardner, a longtime science columnist who sometimes wrote playful pieces. Abrahams asked Gardner about outlets for his own work.

Gardner mentioned an old satire publication called the Journal of Irreproducible Results from the 1950s. Abrahams thought it sounded great, so he revived the journal. It had a Mad magazine vibe. Abrahams later left the journal to start his own publication called The Annals of Improbable Research.

And along the way, Abrahams decided to hand out spoof prizes to publicize his journals. The first Ig Nobels were awarded in 1991. The roster that year was mostly lifetime achievement awards.

One winner was former vice-president Dan Quayle, who famously misspelled the word “potato” by tacking an “e” on the end. But Quayle also committed other gaffes. He once said, “It isn’t pollution that’s harming the environment. It’s the impurities in our air and water.” He also said, “[It’s] time for the human race to enter the solar system.” So Abrahams honored Quayle as a, quote, “consumer of time and occupier of space”—and “for demonstrating, better than anyone else, the need for science education.”

Abrahams also honored, so to speak, a longtime proponent of homeopathy, and a man who argued that ancient civilizations were built by visiting alien astronauts. The Ig Nobel Peace Prize went to Edward Teller—the father of the thermonuclear bomb.

Over the next few years, the prize evolved. It began highlighting actual research that simply had a silly side. Like scientists who personally tested a suit of armor meant to protect against grizzly bears. Or who gave Prozac to clams, or used chickens to measure the windspeed of tornados. A literature award honored the author of a field guide to splattered insects on car windshields.

It was all in good fun. Still, Abrahams knew that winning the Ig Nobel Prize carried some stigma. Some researchers felt it trivialized their work. They got angry with Abrahams. And you can just imagine some know-nothing member of Congress fuming over a research grant they deemed wasteful. Clams on Prozac? Time to cut their budget.

So Abrahams always called the prizewinners in secret before he announced the award, to give them a chance to refuse.

Sure enough, Andre Geim of the floating frog thought seriously about saying no. He wasn’t offended, but he was a young, ambitious researcher. He feared the Ig Nobel might harm his career—make him look unserious or make it harder to win grants in the future. He consulted some mentors.

And in the end, he decided … what the hell. Unlike Eleanor Maguire, he would go for it. A prize for levitating an amphibian? Why not.

Geim even flew to Boston for the ceremony at Harvard. He shared the stage that year with a dozen other ig-laureates. These included a computer programmer who’d built PawSense—software that detects when a cat is walking across your keyboard and immediately blocks any typing. A group of biochemists won for work showing that falling head over heels in love with someone is, neurologically, indistinguishable from severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Geim had a blast.

Each Ig Nobel ceremony includes some common threads and components. There are lots of silly hats, and people often dress up in costumes of mice or beavers or other creatures. The audience is encouraged to throw paper airplanes.

As their prize, winners receive $10 trillion dollars … in Zimbabwean money. Due to corruption and misguided policies, Zimbabwe experienced perhaps the worst inflation in history in the mid-2000s—nearly 80 billion percent per month. So the government really did print $10-trillion dollar bills, which are worth around 4 American cents. And every Ig Nobel prizewinner gets one.

To ease people’s fears over accepting the prize, actual Nobel laureates—usually from Harvard or MIT—present the awards. The Nobelists even come in for some hazing. In one case, a Japanese scientist won an Ig Nobel for figuring out how to extract vanilla-flavored molecules from cow dung. The Nobel laureates were then presented, on stage, with bowls of ice cream flavored with dung-sourced molecules. They had no choice but to eat it.

The ceremony always wraps up with Abrahams saying, “If you didn’t win a prize—and especially if you did—better luck next year!”

As the Ig Nobels have grown in fame, the stuffier folks in the scientific community have loosened up and started to appreciate it. Abrahams now gets around nine thousand nominations per year. And some scientists actually benefit from winning.

Take the duck guy—Kees Moeliker, an ornithologist from Holland. In 1995, the museum where he works opened up a shiny new wing with a huge glass wall. It looked great. The problem was, birds kept smashing into it and dying. Kind of ironic for a building dedicated to studying life. But it did give Moeliker plenty of specimens to study.

One day, a loud thump startled him. He peered down and saw a dead male mallard duck lying there. He trekked down the stairs to investigate.

And he got more than he bargained for. When he arrived, he found another male duck on top of the dead one—having sex with it. Duck necrophilia. It lasted for 75 minutes.

He published a paper about the incident in 2001. Obviously, it won an Ig Nobel Prize. And the prize garnered so much attention that Moeliker became moderately famous. More importantly, people around the world started sending him cases of bizarre animal behavior—including more necrophilia. It’s now an established, if obscure, research area. And it does make you both laugh and think. How can an animal’s wiring get so messed up that it mounts something that’s dead?

Eleanor Maguire got a boost as well. She was the neuroscientist who studied how the hippocampus swells in taxi drivers. She turned down the prize in 2000, but Abrahams persisted and called her back in 2003. This time, she said yes.

And it transformed her life. Her public profile got a big boost. In fact, if you’ve heard about her study before, it probably was not because of the coverage of the original research, but the hoopla from her Ig Nobel.

Maguire also attended the award ceremony in Boston. She took a cab from her hotel to the auditorium, and she and the driver fell to talking. She explained her research, and the cab driver was so thrilled to hear about his big beefy hippocampus that he refused to accept her fare. He was honored to have her.

Years later, Maguire appeared on a panel with three actual Nobel Prize winners. But the moderator introduced her as the most famous one of the bunch. And during the Q&A afterward, nobody cared about the Nobel winners and their boring research. They wanted to know about the cab drivers’ brains. Maguire was thrilled. Accepting the Ig Nobel turned out to be one of the smartest career moves she ever made.

Just for fun, here’s a rundown of my favorite Ig Nobel prizewinners. Ahem:

One study investigated whether most people in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres have hair that swirls in the same direction, clockwise or counterclockwise. The result, quote: “counterclockwise whorls were more frequent in the Southern Hemisphere.”

Another project was honored for, quote “exploding a paper bag next to a cat that’s standing on the back of a cow, to explore how and when cows spew their milk.” The result: cows produce less milk after being startled.

Another study counted the nose hairs of cadavers to see which nostril tends to have more. The result: our nostrils are equally hirsute.

Other studies proved that extreme constipation does not harm the love lives of scorpions; that rollercoasters can hasten the passage of kidney stones; and that Viagra can cure jetlag—at least in hamsters.

My absolute favorite award involved a project to determine whether, quote, “knives manufactured from frozen human feces are … effective tools for skinning or butcher[ing]” game. You’ll have to read my book Dinner with King Tut to find out the answer to that one.

But however silly or gross, some of this work has led to genuinely beneficial results. In 2006, a few researchers determined that malaria-spreading mosquitos were highly attracted to stinky Limberger cheese—that cheese that Pepé Le Pew from Loony Toons loved. The researchers then developed traps using that odor as bait. Mosquitos found the traps two to three times more attractive than humans. This prevented them from biting humans and spreading deadly diseases.

Another experiment determined that electrified chopsticks and drinking straws can make food taste saltier. It was funny stuff. It could also provide ways to give people the pleasant sensation of saltiness while cutting back on harmful sodium in their diets.

Probably the best example of work with unexpected benefits involved a study that won an Ig Nobel in 2024. In it, scientists proved that, quote, “many mammals are capable of breathing through their anus.”

Now, that might sound like something a naughty fifth-grader would dream up for his science-fair project. But the researchers had done the work for the paper in 2020—during the worldwide Covid pandemic. They were trying to develop alternative ways to get oxygen to people whose lungs were failing. And again, the Ig Nobel brought attention to what could be an important treatment. If there’s ever another pandemic, God forbid, this new breathing technique could save lives.

Or what about this geopolitical drama? In October 1981, a Soviet submarine got stranded deep inside Swedish territorial waters. This scared the bejesus out of Sweden. The Soviets insisted the sub had simply gotten lost and blundered into the wrong place. But the Swedes didn’t believe that. It seemed more likely that the Soviets were preparing to invade or attack.

This fear compelled the Swedish military to mount a huge, expensive campaign to monitor their waters for Soviet subs. And throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the Swedish navy did detect noises that sounded suspiciously like submarines. These scares lasted until the Soviet Union collapsed.

Then, in 2003, a paper on oceanography came out. It demonstrated that schools of herring, the fish, can communicate by farting at each other. Fish lack vocal cords, so when they need to yell or alert each other, they sometimes just let fly. Apparently, it can get quite noisy.

Again, this was an obvious project to win an Ig Nobel Prize. And you can probably guess where this is going. Herring are common in the waters around Sweden. And when this research came out, the Swedish military slapped its forehead. They hadn’t been tracking dastardly Soviet subs. They’d been tracking herring flatulence. For years. At the cost of tens of millions of dollars.

Even that stunt with the levitating frog proved to have real-world benefits. As you might know, China has ambitions to land human beings on the Moon, and it’s been sending rovers there. To help test equipment for the missions, Chinese scientists developed a small simulation chamber that mimics the Moon’s lower gravity. It works through magnets—and was directly inspired by Andre Geim’s floating frog.

Oh, and incidentally, accepting the Ig Nobel did not harm Geim’s career. Far from it. He now works in England as Sir Andre Geim. Why the “sir”? Because a few years after his frog experiment, on another late Friday night in the lab, he was goofing around again and pulled another stunt.

He stuck a piece of tape to some graphite and peeled it off. A black, microscopically thin layer of graphite stuck to the tape. And just for kicks, Geim and a colleague decided to investigate the layer’s properties. In doing so, they discovered graphene. It’s now considered something of a wonder-material. Its incredible strength and high conductivity could revolutionize electronics and materials science.

A few years later, Geim got another phone call about a prize for this work. But not from Marc Abrahams. This one was from Stockholm. Geim had won an actual Nobel Prize. And to this day, he remains the one scientist in history to collect both the most important hardware, and the silliest, in all of science.