Astronomer Jules Janssen was desperate to escape the siege of Paris in 1870 and observe an eclipse in Africa, work that he hoped would confirm his discovery of a brand new element, helium. So he devised a plan to escape the city in a hot-air balloon—despite promises by the German army to shoot him as a spy if he dared try.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

In 1870, France and the powerful German state of Prussia got into a war. And Prussia walloped France. In mid-September, just two months after the war began, the Prussian military had already surrounded Paris. Then they laid siege to the 2.5 million people there. No one was allowed in or out.

Except for one person. Of those 2.5 million people, the Prussian army offered one of them free passage to leave—astronomer Jules Janssen. Janssen wanted to observe a solar eclipse in Algeria that December. And the Prussians magnanimously put science above the fray of politics and told Janssen he was free to travel.

So you can imagine the Prussians’ shock when Janssen told them to kick rocks. After months of suffering in solidarity with his countrymen, he refused to accept the easy way out. Instead, with typical French flair, he informed the Prussians that he would take to the air instead. He would soar over the siege in a hot-air balloon.

This rejection enraged the Prussians. Through gritted teeth, they wished Janssen luck. Then they warned him that they planned to shoot his balloon out of the sky—and shoot him as a spy when he landed.

But Janssen was not about to sit home and let this important eclipse pass him by. One way or the other, he was determined to escape Paris.

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and The Disappearing Spoon, a topsy-turvy science history podcast where footnotes become the real story.

Jules Janssen sported a full beard and a waterfall of grey curls off his bald pate. His determination to observe the eclipse in Algeria had its roots in two things: childhood adversity and a need to follow up on some observations from another eclipse two years earlier.

When Janssen was a baby, a nursemaid dropped him and broke his foot. This left him with a permanent limp. But this handicap fueled a fierce resolve to succeed.

He adored science as a child. But with a musician for a father, he couldn’t afford to attend college. So, he worked at a bank by day and built an observation tower on his roof to learn astronomy at night.

Years of drudgery followed as he tried making a name for himself. Elite French scientists mostly snubbed him. But in 1864, at age 40, he landed a spot on a scientific expedition to Peru. Upon arrival, he nearly died of dysentery.

Undeterred, he made more trips abroad and did pioneering work on observing the atmospheres of Mars and the Moon. At last, the French government rewarded him by sending him to observe a solar eclipse in eastern India in August 1868, two years before he vowed to escape Paris by hot air balloon. You might remember this solar eclipse from an earlier episode of this podcast; it was the one that killed the King of Siam.

Janssen had better luck. During the eclipse, he planned to observe the Sun with an instrument called a spectroscope. Spectroscopes separate light into individual colors at different wavelengths.

The spectroscope was normally used to study elements in the lab. Scientists would heat up individual elements until they were glowing hot. At this point, each element produced a characteristic pattern of thin colored lines. It was like a colored barcode.

For example, hydrogen produced a band of red light at 656 nanometers. It also produced an aqua line and two purple lines at other wavelengths. As another example, sodium produced a bright yellow doublet of lines spaced very close together. You probably recognize the color from yellow sodium streetlamps.

Astronomers used spectroscopes, too. By determining the barcode of each element in the lab, then examining the barcode lines produced by sunlight, astronomers could determine what elements made up the Sun. That’s a pretty impressive achievement from 92 million miles away.

During the 1868 eclipse, Janssen wanted to observe the corona of the Sun, its outer envelope. The glare of the Sun normally overwhelms the corona. But the Moon dims the Sun’s body during an eclipse, while leaving the corona visible.

Everything was set, then. The moon slipped into place that morning. And during those seven precious minutes of darkness, Janssen hurriedly analyzed different bands of light with his spectroscope. Right away, he saw the barcode for hydrogen—the red, aqua, and purple lines. Then the blazing yellow doublet from sodium.

But upon closer inspection, Janssen noticed something odd about the sodium lines. In the lab, that doublet line appeared around 589 nanometers. This line appeared just below 588 nanometers.

Now, the one-nanometer difference between 588 and 589 is pretty tiny: less than one-half of one ten-millionth of an inch. But the difference bothered Janssen. In fact, he got so distracted by it that he neglected to do his other observations, and the eclipse passed.

And even afterward, that bright yellow line kept picking at his mind all day. Had his instrument been off-kilter? He didn’t think so. But then what element was that?

Janssen had also been surprised at how blazingly bright that yellow line was. In fact, it was so bright that he wondered whether he could see it outside of an eclipse, even with the full Sun shining. He decided it would be difficult, but doable. He vowed to himself, “I will see that line again.”

Unfortunately, clouds swept over India the day after the eclipse and covered the Sun. So Janssen spent the day reconfiguring his equipment to block out all other wavelengths except around 588 nanometers. The next morning, he tried again, focusing his instrument on the corona. Sure enough, he saw a slight blaze of yellow at 588.

Janssen spent the next month refining his observations. Then he mailed a paper off to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. He didn’t know what he’d discovered and didn’t dare speculate too much. But he sensed it was big—a discovery that could make his career, make all those decades of drudgery worth it.

Unfortunately, intercontinental mail wasn’t exactly a well-oiled machine in 1868. It took his letter two months to reach Paris. And during that time, another scientist scooped him.

The English astronomer Norman Lockyer spotted that same yellow line independently in October 1868, well after the eclipse. But just like Janssen, Lockyer had discovered a way to isolate certain wavelengths of light and study the sun’s corona during daytime.

And unlike Janssen, Lockyer never shied away from leaping to big conclusions. For instance, Lockyer was the first person to propose that the pyramids in Egypt weren’t just tombs, but astronomical instruments.

So as soon as Lockyer saw that bright yellow line, he declared that he had discovered a new, extraterrestrial element. He named it after the sun—helium. And to stake his claim on helium, Lockyer dashed off a paper to the leading scientific body in the world—the French Academy of Sciences.

Now, accounts differ on what happened next. But according to the most dramatic version, Lockyer and Janssen’s papers arrived on the exact same day at the Academy. Had there been an even slightly longer delay on either side, one man might have lost credit forever. Regardless, the two men became instant rivals over helium.

Other complications soon arose. Although other astronomers could not deny the existence of the bright yellow line, some rejected the idea that it arose from a new element. They argued that it was much more likely that the line represented a common element behaving strangely in the sun’s extreme heat. To their minds, helium was bogus.

This, then, was the backdrop for the December 1870 eclipse in Algeria. Janssen needed to travel there to finish the work he’d neglected in 1868. He also wanted to shore up his claim for helium. After all, it was far easier to observe that bold yellow line during an eclipse.

Unfortunately, he had not reckoned on Otto von Bismarck.

In July 1870, the wily Prussian chancellor goaded France into invading Prussia. Bismarck’s military then proceeded to rout the French army.

In a humiliating development, the Prussians even captured the French emperor, Napoleon III. Bismarck then marched on Paris, surrounding it in just five weeks. Some historians call it the original blitzkrieg. People trapped in Paris remember trembling at the booming artillery in the distance, and the smell of burning smoke filling the air.

Bismarck’s men quickly blocked every road, train, and river into Paris. This cut off all incoming supplies. Within weeks, people there were chopping down trees on beloved boulevards for firewood. When food ran low, they took to eating pets; then vermin; then the animals in the zoo. Diaries speak of rat pâté. Victor Hugo compared his stomach to Noah’s ark.

Equally bad, Bismarck’s men cut the telegraph lines out of Paris. As a result, the rest of the world had no idea what Paris was suffering. And the French had no way to communicate with the outside world and rally support.

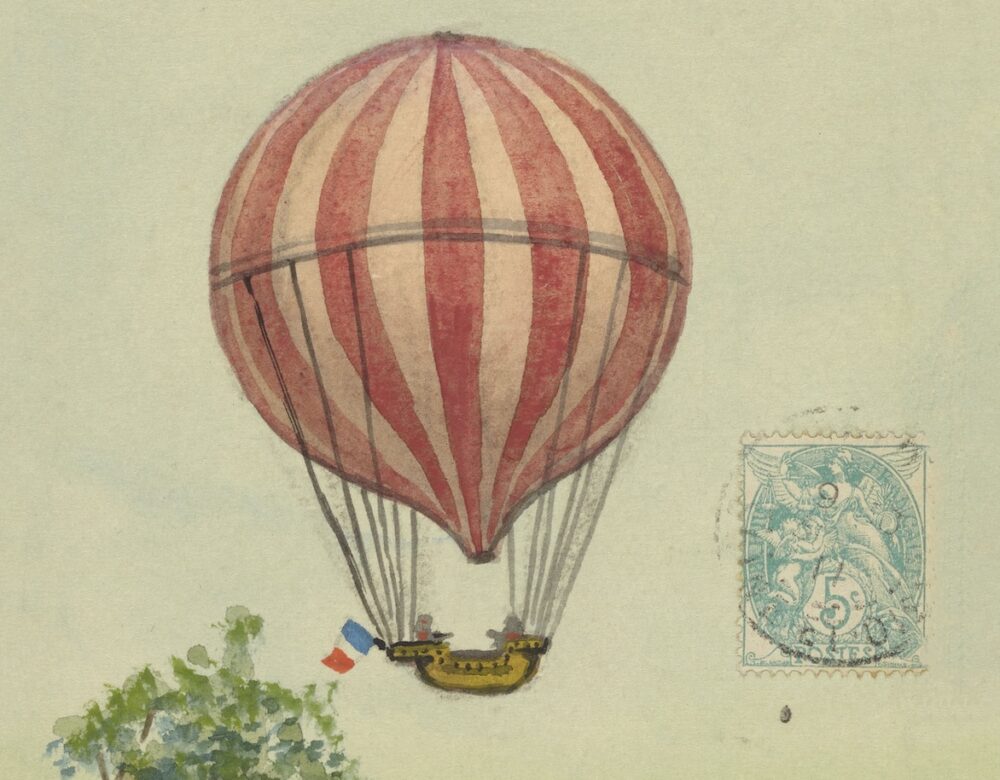

With no way to escape the city, the French government got desperate—and creative. They began sending up hot-air balloons.

Most balloons escaping Paris carried a few passengers, plus sacks of mail and a cage of passenger pigeons. City workers filled the canopies with gas intended for their streetlamps. They sacrificed their reputation as the City of Light for the greater good.

Always stylish, the French gave their balloons dashing names. One was Liberty, another Deliverance. They also honored several scientists by naming balloons after them: Archimedes, Kepler, Newton.

Now, balloons normally take off gently, gaining altitude only gradually. These commando balloon runs out of Paris were not like that. They leapt as high as possible as quickly as possible, in order to dodge the fearsome Prussian artillery outside the city.

Prussian soldiers took potshots anyway. And they sometimes scored hits. One escapee from Paris was Léon Gambetta, the Minister of the Interior and a future prime minister. He suffered a wound to his hand while fleeing and counted himself lucky that that was all.

After his escape, Gambetta set up a French government in exile in the city of Tours. And before long, that government in exile began sending messages back into Paris using microphotography. French engineers had developed a way to drastically shrink the size of text and capture it on film. They could fit three thousand messages in an area just half the size of a modern Post-It note.

These messages were rolled up and slipped inside a goose quill. The quill was then tied with silk thread to a passenger pigeon, which flew back to Paris upon being released.

The exiled government managed to send out 2.5 million messages this way—although many did not reach their destination. The pigeons were often shot down. Some were killed by falcons that Prussian officers trained and sent aloft. Some simply died from cold as the winter settled in.

And all the while, the Prussians continued to shoot down outgoing balloons. Even after the balloons cleared the siege lines, cavalrymen on horseback would pursue them like a foxhunt. Given that the cargo often included messages for the exiled French government, the Prussians treated French balloonists as spies and executed them. No quarter, no mercy, was given.

Despite these risks, as the eclipse approached, astronomer Jules Janssen wanted to make a balloon flight of his own. He simply had to reach Algeria.

Then, out of nowhere, the Prussians sent word that he didn’t have to risk his life after all. In the spirit of fair play, Norman Lockyer—his rival over credit for helium—had brokered an agreement of safe passage for Janssen to leave the city. And incredibly, the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck agreed.

It’s not clear why Bismarck did so. Was he a secret star buff himself? More likely, he saw a chance to win some cheap, easy points in the international community. Sure, let the astronomer go. Why not?

Regardless, Janssen snubbed him. Janssen was a patriot, and he vowed to take his chances in the air. Bismarck, in turn, vowed to bring the astronomer down to earth—promising that any stars Janssen saw on his balloon flight would be his last. They would treat the scientist as a dirty spy.

By December, the French had already launched dozens of balloons. Most were stitched together by dressmakers in the suddenly idle train station in central Paris. The balloon envelopes were awfully patchy, made of cheap calico and designed to last for one flight only.

The matter of Janssen’s co-pilot only complicated things. The co-pilot was a sailor, and he had exactly as much flying experience as Janssen did—0.0 hours between them.

Nevertheless, early on December 2nd, Janssen limped up to the basket of his balloon, La Volta. He climbed in and checked to make sure that the astronomical equipment he had packed was secure. Then, at 6 am, he ordered the men holding the balloon down with ropes and ordered them to let go.

As they shot upward in the dark, Janssen could see the white light of dawn on the horizon, translucent and pure. Beneath him, silent orange fires burned, tiny volcanoes erupting across Paris. As he later wrote, it was a stark reminder “of a lower world with its appetites, passions, violence, and misery.”

Within minutes, the silence was broken by the rifles of Prussian soldiers, whose shots created their own tiny explosions of orange below. Every crack could mean death. The Prussians only had to get lucky once. Janssen and his co-pilot needed to dodge every last bullet.

Thankfully, the gusting dawn winds soon pushed their balloon beyond their adversaries. For the first time in days, the two men relaxed. They’d beaten the siege!

But as they drifted farther, they realized that the dawn winds were not letting up. In anything, they were increasing—buffeting the basket and pushing them faster than expected. Eventually, they could see the Atlantic Ocean looming. They began a desperate attempt to drop altitude before being swept to sea.

Finally, after five hours and 225 miles, they crashed down into a field just short of the ocean. They were immediately surrounded by farmers, who peppered them with questions about Paris. The farmers then served the famished aeronauts their first hearty meal in months, a lunch of roast chicken, butter, and eggs.

Janssen rested for a few days, then boarded a train for Tours, where the exiled French government was. There, he relayed a secret message to the escaped minister Léon Gambetta. Janssen had been acting as a spy after all. He then raced off to Algeria.

At this point, I would love to tell you that Janssen’s quest ended happily—with him spotting that brilliant yellow line in Algeria and confirming the reality of helium. But life is not so tidy.

After enduring months of siege and escaping in the most dramatic way possible, Janssen arrived in Algeria to find the skies overcast. As one historian said, he’d been “shut behind a cloud-curtain [even] more impervious than the Prussian lines.” There would be no observations, no yellow lines.

It’s enough to make you groan. Such a lofty escape, such a deflating finale. But Janssen took solace in one thing: that Norman Lockyer, observing the eclipse in Sicily, suffered the same fate of cloudy skies.

Today, we know that that blazing yellow line in sunlight does in fact represent helium, the second most common element in the Sun. Janssen and Lockyer now share credit for discovering it, and it remains the only element first discovered on another celestial body. How fitting, then, that the man who first spied it had once taken to the skies himself in pursuit of scientific glory.