Winning a Nobel Prize is a good thing—mostly. The fame, the fortune, the hallowed place among other scientists of note. But surprisingly often, Nobel laureates shift away from legitimate scientific work and into promoting bizarre things like homeopathy, ESP, AIDS denialism, and worse. Psychologists have started thinking about what drives this trend, and it turns out to be way more than ego.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

In 1956, three scientists at Bell Labs in New Jersey won a Nobel Prize for developing the first transistor. The announcement sent ripples of joy throughout the office. A trio of Nobel laureates! Wow.

Management gathered everyone in an auditorium to gawk at the sudden celebrities, and each scientist made some remarks. The last to go was physicist Walter Brattain. Partway through, he got choked up, and nearly started crying. Very touching.

But the thing was, Brattain wasn’t crying in joy. He was worried. At age 54, he still probably had a decade or two of productive research ahead. But he admitted he feared that winning the Nobel Prize would ruin him.

Which was a strange reaction. Winning the Nobel Prize is a good thing, right?

Yeah, mostly. Your name will be etched in history alongside Einstein and the Curies and other legends. You get a big cash prize. Nobel winners even live two years longer on average compared to those who were merely nominated.

But there are downsides to winning a Nobel. And today, we’ll examine some of the pitfalls. Including a notorious “disorder” sometimes called the Nobel Disease.

These days, Richard Feynman is a legendary physicist, as beloved for his manic personality as for his brilliant research. But in the late 1940s, he wasn’t feeling very brilliant.

He’d just finished working on the Manhattan Project to build an atomic bomb. And given that impressive pedigree, people were pressuring him to research Big Things—to grapple with fundamental questions in physics.

And Feynman hated it. He was a freewheeling, mischievous person, and that pressure was ruining physics for him.

So he decided, no more. From then on, he was only going to do fun physics. And a few days later, a problem seized his attention.

He was a professor at Cornell, and one day in the cafeteria, he saw a student horsing around. The lad was tossing a plate in the air and catching it, like you would pizza dough. And Feynman noticed something.

As the plate flew upward, it both wobbled and rotated. The plate also had the Cornell University logo on it. And in watching the logo spin, Feynman noticed that for every one rotation, the plate wobbled twice. He wondered why. Was the student simply throwing the plate a special way? Or was something deeper going on?

He decided to find out. He started playing with the equations that describe the motion of a spinning, wobbling disc. The math proved trickier than expected. But he kept plugging away, and finally got an answer. It wasn’t just the way the student threw the plate; something deeper was going on. As long as you throw the plate upward at a small angle, it will always wobble twice for every one rotation.

Feynman thought this was pretty neat. He showed some other scientists in his department. They thought … that it was pretty dumb. Why are you wasting your time on wobbling plates? Do some real physics.

But here’s the thing: the math that Feynman worked out for the spinning plate later came up when he was studying how electrons orbit an atomic nucleus. Feynman simply tweaked the equations, and voilà—they gave him real insight into, yes, fundamental physics. He later won a Nobel Prize for this work. And it all started with him goofing around with unimportant equations about an unimportant problem.

Feynman never forgot that lesson. Have fun with physics, and big results might follow.

Now, compare that to Walter Brattain, who nearly started crying after winning a Nobel for the transistor. Brattain thought his career was ruined: as a Nobel laureate, he knew he’d feel pressure to work on Big Things. So in his speech at Bell Labs, he vowed to keep having fun with physics. As he said, “I know all about this Nobel-Prize effect. And I am not going to let it affect me.” Observers were touched.

But it wasn’t to be. Brattain caved to the pressure. Even within a few weeks, he got shunted onto Big Problems, where he made no progress. Just as he feared, his career stagnated.

So that’s one downside to a Nobel Prize—winners feel pressure, internal or external, to work exclusively on Big Topics. As one historian said, “They fail … to plant the little acorns from which the mighty oak trees grow.”

There are other bad effects, too. One is a byproduct of being a scientific celebrity. Everyone wants a piece of you. You’re constantly being asked to chair some committee or give some speech at some conference. It’s a huge time-suck. Our best minds suddenly become far less productive.

One Nobel laureate, economist Milton Friedman, summed this up nicely. He said, “I myself have been asked my opinion on everything from a cure for the common cold to the market value of a letter signed by John F. Kennedy. Needless to say, the attention is flattering, but also corrupting.”

Now, the word “corrupting” might seem strong. But it’s not. Consider what’s called the Nobel Disease, or Nobelitis—the tendency of Nobel laureates to subscribe to wacky ideas.

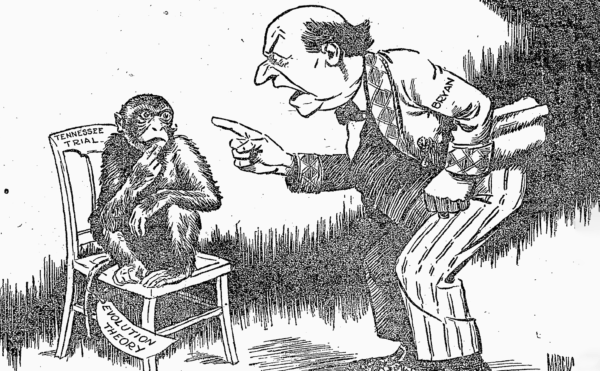

Historically, there have been laureates who believed in ghosts, cold fusion, telepathy, homeopathy, telekinesis, ESP, and more. One laureate, the chemist Richard Smalley, even declared that he’d used chemistry and physics to deal a “death blow” to evolution.

Several laureates also subscribed to eugenics, the discredited pseudoscience of breeding supposedly “better” humans. In fact, one of the colleagues whom Walter Brattain shared his Nobel Prize with, William Shockley, was an ardent eugenicist.

And to be clear, those afflicted with Nobelitis aren’t just being provocative or indulging in philosophical speculation. They cling to these beliefs. They fight for them tooth and nail.

One especially kooky Nobel laureate was Kary Mullis. Mullis was a counterculture hippie-type. He credited his great, Nobel Prize–winning idea to a vision he had while dropping acid. The idea was the PCR machine, where PCR stands for polymerase chain reaction.

Essentially, PCR provides a way to copy and amplify DNA. Even if you start with just one strand of DNA, a PCR machine can produce billions of copies to sequence and study. It’s hard to overestimate how important PCR is. It’s arguably the most important biological tool developed in the past fifty years.

Which made it all the more baffling to hear Mullis talk about his personal beliefs. He spoke openly about his love of astrology. He said aliens visited him, including one that looked like a fluorescent raccoon. More perniciously, he denied that human beings cause climate change. He also denied that HIV causes AIDS.

In fact, Mullis once confronted a biologist who won a Nobel Prize for discovering HIV, Luc Montagnier of France. When they met, Mullis pestered him with bad-faith questions about the supposed lack of evidence for HIV causing AIDS. Montagnier got fed up and eventually just walked away. And I don’t blame him.

But of course, as a Nobel laureate, Montagnier had his own kooky ideas. They involved DNA. Montagnier swore up and down that DNA emitted electromagnetic waves. He also claimed that DNA could mystically imprint itself on water. He said he proved this with an experiment.

He put DNA into a test tube with some water. He placed a second test tube nearby with just water inside—no DNA. Supposedly, the DNA in the first test tube emitted electromagnetic waves that imprinted a signature on the water in the other test tube.

So much so, that Montagnier claimed he could reconstruct the original DNA solely from the water in the second tube. It was telekinesis meets homeopathy. He then added his belief that Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, autism, and multiple sclerosis were all caused by the destructive electromagnetic waves from microbial DNA.

So what causes Nobel Disease? It’s probably a combination of factors.

In Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, there’s an interesting story. In his youth, the idea of killing animals appalled him. So, he became a vegetarian—at least for a while. Because one day, a friend began frying up some fish, and the smell had Franklin drooling.

He remembered his morals—remembered how wrong it was to slaughter animals. Oh, but that smell! Mmm. He couldn’t stop staring at the fish.

Then he remembered something else. He’d once seen someone cut open a fish of this same species. Inside its stomach, there were several smaller fish. And if this fish was eating others, Franklin reasoned he had the right to eat it in turn. With his conscience now clean, Franklin dug in.

Franklin then commented, “So convenient a thing to be a reasonable creature—since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.”

That quip is relevant to Nobel Disease. Nobel laureates are smarter than average. So, they’re great at coming up with reasons to justify whatever they want to believe, however silly. Their intelligence also allows them to poke holes, however specious, in arguments against their silly beliefs. Intelligence can be abused sometimes.

So can creativity. Nobel laureates are more creative than average scientists. That’s how they come up with brilliant ideas—some of which seemed nuts when they were first proposed. But it can be hard to shut down the part of your brain that comes up with nutty ideas.

Creativity also correlates with being open-minded. But being open-minded to bad or pernicious ideas is not a positive thing. Especially when you can just invent plausible-sounding justifications.

Nobel laureates need tenacity, too, and unshakable self-confidence. It’s hard enough to succeed in science—especially with groundbreaking work where people initially doubt you. You might even need a screw-you, go-it-alone attitude. Which is praiseworthy when it leads to discoveries.

But again, if you’re rewarded for being tenacious and clinging to possibly nutty ideas, it can be hard to shut that part of your brain off and realize that you’re embracing dumb, or even dangerous, ideas. Psychological studies have also found that intelligent people tend to delude themselves into thinking that they’re immune to mistakes. As a result, they let their guard down and get seduced into poor thinking.

One final contribution to Nobel Disease is the ego boost that scientists get. After they win, people fawn over them, flatter them. They feel invincible. In this state, it’s hard to stay humble and admit you might be wrong.

Even worse, that inflated ego can lead laureates into the delusion that they’re geniuses at everything, even beyond their area of expertise. They start spouting off about economics, or politics, or race.

But psychologists have noticed that brilliance doesn’t readily transfer from one domain to another. They make an analogy with sports. If you’re tall and fast and strong, you’ll likely be good at most sports. But being a world-class basketball player doesn’t automatically make you a world-class football or baseball player. Each sport requires specific skills and instincts.

The same goes for intellectual endeavors. Brilliance in physics doesn’t automatically translate to brilliance in biochemistry—much less psychology or politics. But for whatever reason, when a Nobel laureate speaks outside their field, people assume they must have great insight.

To be fair, there are exceptions—people who’ve proved brilliant in multiple fields. Consider the chemist Linus Pauling.

In the 1920s, Pauling determined how to apply quantum mechanics to chemistry. In doing so, he figured out, for the first time, what really happens when atoms bond to each other. And considering that chemistry is essentially the study of how atoms form bonds, this revolutionized the field.

A colleague once remarked that, after Pauling, chemistry could now be understood, rather than just being memorized. That might be the greatest compliment ever paid to a scientist. Pauling won a richly deserved Nobel Prize for this work in 1954.

And he didn’t stop there. He figured out the genetic roots of sickle-cell anemia, and became the first person ever to trace a disease back to a specific mutation in DNA. He also came within a whisker of discovering the double-helix structure of DNA before anyone else.

Just as impressive, Pauling was a rare scientist who was politically savvy. He won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1962 for his fight against the proliferation of atomic bombs. He’s still the only person in history to ever win two unshared Nobel Prizes.

And yet—for all his brilliance in multiple fields—even Linus Pauling suffered from Nobel Disease.

His case involved medicine. Pauling suffered from nasty colds his whole life. In 1965, a doctor wrote to Pauling and suggested taking megadoses of vitamin C. Pauling did, and reported feeling better.

From everything we know now, this was likely a placebo effect. But Pauling became a true believer in vitamin C. He started taking up to 40,000 milligrams a day. That’s hundreds of times the recommended daily amount.

This much vitamin C can cause cramps, heartburn, and other problems, even kidney stones. And even if it doesn’t, your body sheds excess vitamin C in urine. And Pauling’s colds never actually went away. He still suffered from them, although he swore they were less severe. Wildly, he even claimed that vitamin C could help cure schizophrenia, AIDS, and cancer.

In reality, Pauling was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1991. But he claimed that vitamin C had potentially put his cancer off by 20 years—which is of course impossible to prove. He died a few years later.

Controlled studies have shown mixed results with vitamin C. It’s possible that it can shorten the duration and severity of colds. But it cannot prevent them. And yet, to this day, many people still believe that big doses of vitamin C will cure or prevent colds. After all, didn’t a Nobel Prize winner say so?

Before we wrap up, I want to mention a bonus episode at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. It’s about the biggest mistakes in Nobel Prize history—cases where prizes were awarded for bogus research. Even Nobel prize winners make dumb blunders. That’s patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

To be sure, there were scientists who believed in kooky things even before the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901. The co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace, believed in ghosts and attended séances. Isaac Newton wasted years of his life conducting alchemy experiments and hunting for hidden codes about the apocalypse in the Bible.

But the prestige of a Nobel Prize brings out the worst in some people—inflating their egos, giving them an outsized sense of importance. You might have heard that it’s Nobel Prize week right now, with the awards being handed out. And to be clear, most scientists are thrilled to win the prize and deserve the attention and praise that accompanies it. It’s the culmination of a lifetime of work, everything they’ve ever dreamed of.

But as they say, be careful what you wish for. You just might get it—and all the baggage that comes along, too.