Exactly a century ago, teacher John Scopes was charged with the “crime” of teaching evolution. But Scopes was hardly a defiant Galileo, nobly standing up for truth. In fact, he never even taught evolution. But despite the unseemly origins of the Monkey Trial, Scopes proved himself a genuine hero.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

For William Jennings Bryan—a three-time presidential nominee and former Secretary of State—giving a high school commencement speech might seem like a letdown.

But in late spring 1919, Bryan agreed to do just that for his hometown of Salem, Illinois. Practically the entire county turned out to see their hero. And although he was pushing 60 years old, Bryan could still put on a show. He had the whole town spellbound until…

…someone started laughing.

Bryan’s eyes darted to the mischief-maker. It was a teenager from the graduating class—a skinny, owl-y fellow with glasses and thin red hair. He’d cracked a joke to his friend in the middle of Bryan’s speech.

The old man’s mouth hardened, and his black eyes bored in on the lad. The crowd no doubt hushed as Bryan held the glare for several devastating seconds. Then he cleared his throat and continued.

As a veteran speaker, Bryan did not let the interruption derail him. And he likely would have forgotten the incident entirely. Except, a few years later—in 1925, exactly a century ago—he ended up prosecuting that same troublemaking young man in court, in a trial that would captivate the nation.

Because that owl-y redhead was none other than John Scopes, the soon-to-be-teacher at the center of the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial.

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and The Disappearing Spoon, a topsy-turvy science-y history podcast where footnotes become the real story.

John Scopes studied geology in college and always wanted to get his Ph.D. in that field. But he lacked the money. So, in the summer of 1924, he applied for some teaching jobs.

Luckily for him, a science teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, left the local high school in the lurch by fleeing for another job just days before the school year started. The district was desperate for a replacement and hired the 24-year-old Scopes despite his complete lack of experience.

Dayton was a prim town, full of stately homes with pretty gardens. It had two paved roads and nine churches for its 1800 inhabitants, mostly Baptists and Methodists.

Scopes taught general science and coached football, despite his scrawny frame. The year passed uneventfully until March. That month, the Tennessee legislature passed a law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools.

As a man of science, Scopes thought the law sounded dumb and ignored it. So did everyone else in Dayton. It was just some politicians grandstanding.

But not everyone ignored it. The ACLU, the American Civil Liberties Union, thought the law was an abomination, not to mention unconstitutional. The organization had been founded just five years earlier and wanted to make a splash, so it decided to challenge the law.

The problem was, the ACLU was headquartered in New York. It had no standing in Tennessee. So, the group took out newspaper ads in the state, announcing their hopes to find a willing defendant.

One ad reached a 31-year-old engineer in Dayton named George Rappleyea. Rappleyea worked at a chemical plant in town that made coal and a coal byproduct called coke. Or it used to: the plant had nearly gone bankrupt. It was Dayton’s big employer, and its slump had brought the town down with it.

So, when Rappleyea saw the ACLU ad, he sensed an opportunity. He decided a teacher in Dayton should challenge the law. The publicity could boost Dayton’s profile and bring in jobs.

Frankly, I am not sure what Rappleyea was thinking. Because of him, Dayton became a worldwide laughingstock. But hey, maybe any publicity is good publicity.

Regardless, Rappleyea held a meeting at a drug store with a few local muckety-mucks and pitched his idea. They were equally excited. They decided to recruit the town’s new science teacher, John Scopes.

They selected Scopes not for his eloquence or bravery or intelligence. They chose him because, as a young bachelor from out of state, he didn’t have any family nearby that would suffer from any threats or abuse.

Now, this behind-the-scenes maneuvering might conflict with your image of the Scopes trial. It did with mine. I had always pictured Scopes as a noble iconoclast, someone standing up for scientific truth like a latter-day Galileo. And Scopes did believe in evolution, sure. But in reality, the whole trial was engineered—a publicity stunt.

At the drug store, Rappleyea and his cronies sent two boys out to fetch Scopes. The teacher wandered in a few minutes later, blinking behind his glasses. Rappleyea laid out his idea.

Scopes hesitated. He was a quiet fellow who hated stirring up trouble. Plus, there was another problem. That spring, Scopes had taught biology at the local high school. But on the day that evolution came up in his lesson plans, Scopes was out sick. So, the class skipped the topic. Which meant Scopes never actually taught a lesson on evolution. The only thing he’d done that might have been illegal was mention evolution in another general science class.

Rappleyea batted away this pesky objection and convinced a reluctant Scopes to become the defendant. A few days later, a mock “arrest” took place, and local prosecutors filed charges.

That prosecution team looked formidable. One member was a future U.S. Senator. The team also included a man named Sue Hicks, who later inspired the Johnny Cash song “A Boy Named Sue.”

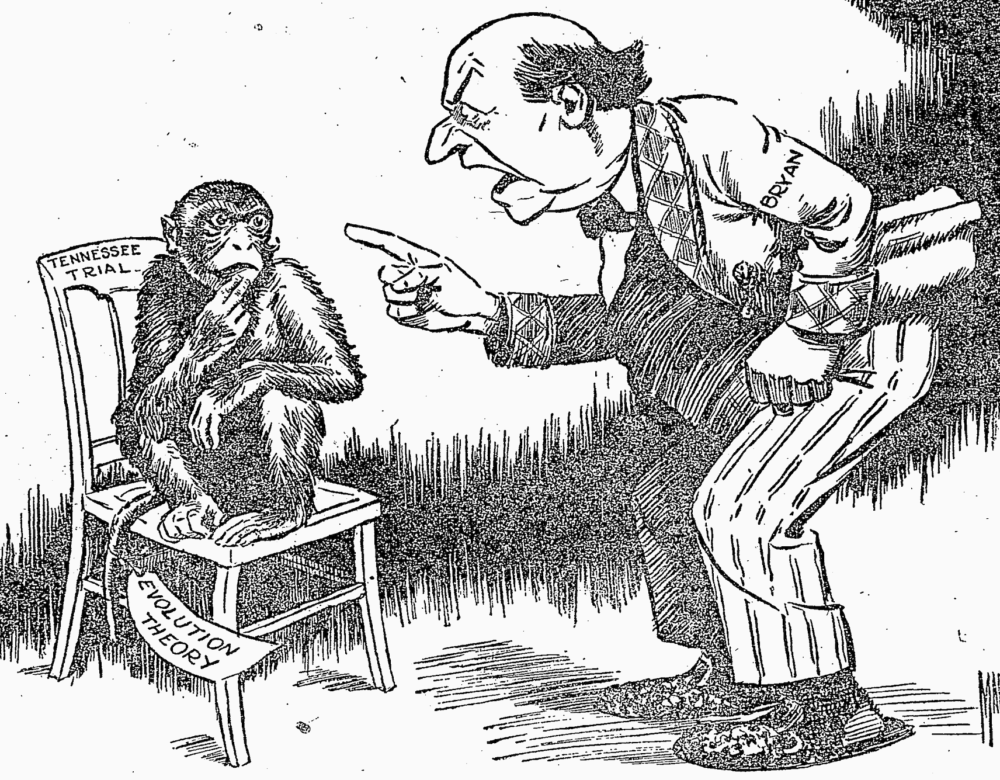

Most formidable of all, William Jennings Bryan joined the team. Bryan was old and creaky then, suffering from diabetes. He didn’t even live in Tennessee. But as a fundamentalist Christian, he despised evolution and wanted to see the idea crushed. He promised a “duel to the death” in court.

Scopes was aghast to hear about Bryan joining the prosecution. He must have thought back to his rude interruption of Bryan’s commencement speech and trembled. The old man could finally get his revenge.

For his defense team, Scopes hired a local lawyer, but the overall case was orchestrated by the ACLU in New York. And they pretty much ignored their client. Scopes had to read the newspapers to find out what plans his own lawyers had for his case.

Then something unexpected happened. A lawyer in Chicago named Clarence Darrow volunteered to defend Scopes.

Darrow was a controversial figure. As a young struggling professional, he’d paid his bills by playing illegal poker games. In the courtroom, he made a name for himself defending radical labor activists—including one who had planted bombs to take out his enemies. Darrow actually got caught bribing a juror in that case. Later, Darrow defended Leopold and Loeb, two teenagers who had murdered a young boy just to prove they could commit the perfect crime.

Politically, Darrow and Bryan were both populists, fighting for the little guy. But they diverged over religion. Whereas Bryan was fundamentalist, Darrow was agnostic, even atheist. He resented Bryan for shoving Christianity down people’s throats.

That’s why Darrow volunteered to defend Scopes: he wanted a heavyweight showdown with Bryan over the ultimate truth of evolution.

Which is exactly why the ACLU did not want Darrow on their team. The ACLU lawyers supported evolution, yes. But they believed the best way to invalidate the Tennessee law was to focus on narrow legal issues, like the violation of church and state. Fighting over the truth of evolution would be too polarizing. So, they rejected Darrow’s offer.

But Scopes did not. At some point that spring, the ACLU decided that heck, maybe they should bring their client in and update him on his own case. So, Scopes rattled up to New York in a train. And, while there, he made an impassioned speech begging the ACLU to join forces with Darrow. They needed star power to counteract William Jennings Bryan. Otherwise, he would have the jury eating out of his hands.

The ACLU scoffed at Scopes. What did he know about his own case? But despite his appearance, Scopes could be tough. He stood his ground, and the ACLU agreed to hire Darrow. And with that, a heavyweight title card was set. Tennessee versus Scopes; Bryan versus Darrow; and fundamentalist religion versus evolution.

Clarence Darrow and the ACLU lawyers holed up at a creaky mansion in Dayton that they joked was haunted. Less amusingly, they had to hire police protection because of rumors that the Ku Klux Klan would attack them.

Before the trial began, a grand jury had to indict Scopes. Now, normally, defense lawyers hope to get their case dismissed before a grand jury. But Darrow and the ACLU wanted the case to proceed.

So, they called as witnesses some of Scopes’s former students. They would testify about all the wicked scientific ideas he had filled their heads with.

The problem was, Scopes had mentioned evolution only in passing during class. Which meant his students didn’t really understand it. The defense team, therefore, coached the students on what to say. Then the students parroted the lawyers’ words back. This was irregular, to say the least.

But it worked. The grand jury indicted Scopes, and the trial opened July 10th.

Just like George Rappleyea hoped, the trial garnered loads of attention. The grounds outside the courtroom were packed with preachers and political rabble-rousers. Vendors were slinging everything from hot dogs and lemonade to stuffed monkeys. The press descended in droves, too, including H.L. Mencken of Baltimore, who wrote scathing dispatches.

Inside the courtroom, things started badly for Scopes. The presiding judge was up for re-election and was trying to impress the locals. So, he opened the trial with a prayer. Darrow objected, which irritated the judge from the jump.

Then, during jury selection, Darrow asked a prospective juror a dumb question. The man was a preacher, and Darrow asked whether he’d ever railed against evolution from the pulpit. When the preacher answered of course, all the other prospective jurors started applauding. Meanwhile, Scopes could only sit there nervously, blinking behind his glasses and badly regretting what he’d gotten himself into.

The weather was so sweltering over the next ten days that the judge held sessions outdoors sometimes.

The prosecution’s argument was simple. Tennessee had a law, and John Scopes broke it. Case closed.

In contrast, Darrow and the defense tried to make the case about evolution. To this end, they called in a dozen scientific luminaries to testify. But the grouchy judge excluded all of their testimony from court. This put Darrow and Scopes against the wall.

Especially because Bryan was in rare form—eloquent and dynamic. Even Scopes admitted that Bryan hypnotized him at times. Indeed, Bryan would have steamrolled the defense if not for one inspired move.

Toward the trial’s end, Darrow decided to call an expert witness on the Bible. He wanted to highlight contradictions in it and show that using the Bible as a scientific text was silly. And as his expert witness, he called up none other than William Jennings Bryan.

This move was even more irregular than the judge starting court sessions with prayers, or the defense coaching witnesses to condemn their client. The judge never should have allowed it. But apparently, he wanted to see the heavyweight showdown as much as everyone else. So, he allowed Bryan to take the stand.

Frankly, Darrow destroyed Bryan. They debated several head-scratchers in the Bible, like where Cain got his wife from, and how Joshua made the Sun stand still in the sky. Darrow wasn’t trying to mock Christianity. He simply wanted to undermine a literal reading of the Bible. Bryan could do little but bluster; he looked foolish.

Darrow then pulled a second clever move. Bryan was the last witness in the trial. Only closing arguments remained after him. And given how mesmerizing a speaker Bryan was, he would have the chance to redeem himself then.

But Darrow decided to waive his closing argument. That meant the prosecution would not get the chance to present theirs, either. The last impression of Bryan from the trial would be him fumbling around on the stand. He was furious.

Unfortunately for Scopes, this clever gambit was not enough. Like everyone expected, the jury found Scopes guilty. The judge fined him $100. That’s $1800 today. Scopes was now a convicted criminal for teaching evolution.

Still, the prosecution could not claim victory overall. The verdict was appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court. And probably wisely, those justices found a reason to dismiss the conviction on a technicality. Under Tennessee law, all fines over $50 must be levied by juries. So, the judge who fined Scopes $100 had technically violated the law.

In the end, then, both sides kind of lost. With the conviction thrown out, the prosecution could not claim much satisfaction. Meanwhile, Scopes was spared the fine but was vilified as an atheist and still had the stain of the original conviction on him.

Bryan suffered even more. His performance at the trial burned him out, and his diabetes flared up terribly. He died in Dayton just five days after the trial ended. So, he never took part in the appeal.

Neither did Clarence Darrow. He had made his point about evolution during the original trial, and he moved on to stir up controversy elsewhere.

Surprisingly, Scopes didn’t participate in the appeal, either. By the initial trial’s end, he was sick of the whole business. He actually received dozens of offers to cash in on his fame—invitations to write articles and give lectures, even a movie contract. He turned every offer down.

Instead, he went back to his first love, geology. He enrolled at the University of Chicago and eventually got his Ph.D. While attending school, he frequently dined at the home of Clarence Darrow.

During the Great Depression, Scopes declared himself a socialist and ran for Congress. He got trounced. He finally got a job with a gas company in Louisiana and moved down there. For most of his life, he refused to talk about the court case.

But in his final years, he did open up a bit and give some interviews. One surprising fact that emerged was that he deeply respected William Jennings Bryan, despite Bryan prosecuting him. Scopes even admitted that they had shared a laugh over him interrupting Bryan’s commencement speech back in 1919. Although he was a stern religious fundamentalist, Bryan had a sense of humor about the absurdities of life.

Scopes was a heavy smoker, and he died of cancer in 1970—just three years after Tennessee finally revoked its anti-evolution law. I admit that when I started this story, I expected to write about a much different Scopes. A firebrand, an iconoclast. But that’s just not the truth. Scopes had not particularly wanted to challenge the law. Other people did, for publicity, and Scopes soon regretted getting involved.

But to me, that makes him all the more admirable in some ways. They say that courage is not the absence of fear. It’s feeling fear and going forward anyway. That’s how I’ve come to see John Scopes. The famous Monkey Trial may have been manufactured. It’s not the pure Galilean morality tale that we’d like.

Nevertheless, it’s still a touchstone for science—as is Scopes’s reluctant heroism. We can’t all be iconoclasts and fiery truthtellers. But he set a wonderful example of what people can do to stand up for scientific truth—an important model any time science faces threats from benighted foes intent on destroying it.