Richard Meinertzhagen was the greatest bird biologist of his day—as well as a spy so colorful that the character of James Bond was based on him. But Meinertzhagen was also a liar and a thief. And as researchers later discovered, he perpetrated the biggest fraud in the history of ornithology.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

The moment Pamela Rasmussen saw the article, she froze in fear.

Rasmussen was an ornithologist at the Smithsonian Institution. It was 1996, and she was putting together a field guide on the birds of India. She had tens of thousands of specimens and field reports from across the subcontinent to examine. It was overwhelming.

Thankfully, she had a few guiding lights—ornithologists she could draw on who’d done reliable work there. Without them, she would flounder.

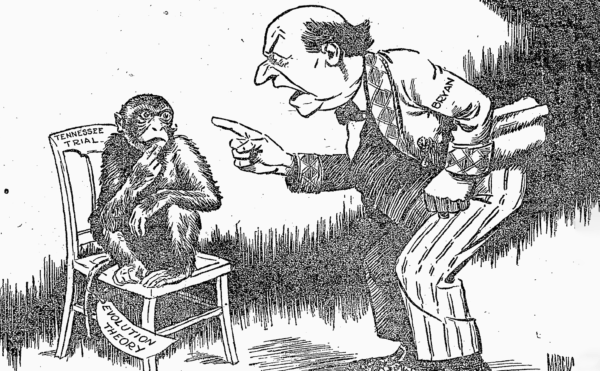

Which is why the article disturbed her. It was about Richard Meinertzhagen, one of those trusted sources. Before his death in 1967, he was considered the great ornithologist of his generation. He did fundamental work in India, collecting 14 species that no one else had seen there.

But the article was accusing Meinertzhagen of fraud. The accusations centered around redpolls — brown-and-white finches with what looked like a smear of strawberry jelly on their chests. Meinertzhagen had collected some in France once, before donating them to a museum in London.

At least that’s what he’d claimed. According to the article, Meinertzhagen had not collected the specimens. He’d stolen them from another museum in England. He had then changed the labels to make it look like he had found them in France, all to prove a pet theory of his.

Rasmussen didn’t believe the article at first—she didn’t want to. But the evidence it laid out was damning. She finished it with a sinking feeling.

To be sure, the accusations involved only birds in England. Maybe his work in India was still sound. And Meinertzhagen had a reputation as tireless, someone willing to tramp farther and search more widely than anyone else. So maybe he really had found those 14 species no one else recorded in India.

But doubts were already gnawing at Rasmussen. Her career, her reputation, were on the line with this field guide. She decided right then and there to get to the bottom of this. Who really was Richard Meinertzhagen, really? And how much could she trust him?

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and The Disappearing Spoon, a topsy-turvy science history podcast where footnotes become the real story.

Richard Meinertzhagen was born in 1878 into an international banking family that was second in prestige only to the Rothschilds in Europe. Meinertzhagen overlapped with Winston Churchill in school and claimed to be descended from a king of Spain. Family members headed the Bank of England and the London Stock Exchange.

He loved biology from a young age. He supposedly sat on Charles Darwin’s knee once, and as a teenager, he spent countless hours skinning and preparing specimens at the Natural History Museum in London. In fact, he learned the art of preparing birds from one Richard Sharpe—the very man whose redpolls he would later be accused of stealing and claiming as his own.

Meinertzhagen grew up into an imposing man—six-foot-five with a booming voice and a dashing mustache. He longed to become an ornithologist, but his father forced him to join a branch of the family bank in Germany at age 17. He despised the work and soon quit to join the British army. He served in India and Burma before ending up in Kenya.

At this point, Meinertzhagen’s biography gets a bit murky. Mostly because he was a fabulist—he just made up wild tales. For instance, his memoirs and even diaries are filled with stories of atrocities he helped commit in Kenya. Burning down villages, mowing people down with rifles. He even talked of roasting a Kenyan warrior on a spit and eating him.

Historians have found zero evidence that any of that happened. It’s unclear why Meinertzhagen invented these stories. Perhaps he enjoyed shocking people.

In truth, he spent much of his time in Africa haughtily ignoring orders and doing science. He mapped the terrain, collected animal skins, painted wildlife, and conducted a census of animals on the Serengeti. However much of a liar, he took science seriously and did good work.

Still, he was involved in two disturbing events in Africa—things that really did happen.

Once, he sicced his beloved dog Baby on some baboons; he hoped Baby would kill a few, perhaps for specimens. Instead, the baboons ganged up and tore Baby to pieces. A furious Meinertzhagen rounded up a platoon of soldiers. They hunted the baboons down and shot every last one. It was pretty ugly.

Far worse was the Nandi massacre of 1905. The Nandi were a tribe in Kenya who clashed with British officials over incursions into their territory. They especially hated railroad lines and telegraph poles. They sabotaged them whenever possible.

Lt. Meinertzhagen reached out to their leaders and proposed a meeting. He said the British wanted to work toward peace.

No one quite knows what happened at the meeting—stories differ. We do know the two sides met in a clearing. Meinertzhagen had five men with him, the Nandi had two dozen.

Meinertzhagen later swore that one of the Nandi shook his hand to open the meeting—then treacherously yanked him forward, to throw him off-balance. It was a signal for the other Nandi to attack. Luckily, Meinertzhagen said, his men opened fire and killed the traitors.

Other sources claim that Meinertzhagen was the double-crosser—that he yanked the Nandi leader during the handshake to initiate his own sneak-attack. Still other sources say that the British hid a machine gun behind a rise near the meeting site and mowed the Nandi down when Meinertzhagen’s men were still fifty yards away.

Regardless, the outcome was the same: two dozen slaughtered Nandi leaders. This decapitated the rebellion, which soon died away.

Now, British colonial officials were not exactly kind fellows. They committed plenty of atrocities. But even they were horrified at whatever Meinertzhagen did. Three separate court hearings probed his handling of the Nandi meeting. He beat all the charges, but he got shipped out of Africa in disgrace.

Not that it really harmed a charmed upper-class fellow like him. He kept his head low for a bit, worked his connections. By the start of World War I, he was back in India doing intelligence work—espionage. He later shifted to Palestine, where the British army was fighting the Turks.

During slow days on the front, he would commandeer the optical instruments that troops used to track incoming artillery. He would spend a happy afternoon calculating the velocities of birds soaring overhead.

Meinertzhagen’s exploits in Palestine have become legendary. Historians have written whole books about them. His primary responsibility involved running a network of Jewish spies within the Turkish army, work that won him several medals.

He also met Lawrence of Arabia. Lawrence described Meinertzhagen as a man “so possessed by his own convictions that he was willing to harness evil to the chariot of good.” Meinertzhagen, however, was less impressed with Lawrence. In fact, Lawrence once supposedly confessed to Meinertzhagen that he was a fraud. “Someday,” he wailed, “I shall be found out.”

After the war, Meinertzhagen married a woman named Annie. He eventually rose to the rank of colonel and continued to lurk on the edge of British espionage. He didn’t do much during World War II, beyond helping evacuate soldiers at Dunkirk.

But that didn’t stop him from spinning wild stories about his exploits. Conveniently, if anyone challenged the veracity of his tales, he either browbeat them with his booming voice or claimed that the incident was hush-hush and that he could not say any more.

One story he told involved meeting several times with Adolf Hitler in the 1930s. He was there to beg for the lives of endangered Jews. But the meetings supposedly had their comic moments. At one, Meinertzhagen said, Hitler walked up to Meinertzhagen, snapped into a Nazi salute, and bellowed “Heil, Hitler.” A flustered Meinertzhagen responded by saluting back and braying, “Heil, Meinertzhagen.”

You can imagine this story getting raucous laughs at dinner after a few bottles of wine. But really, it makes no sense. Why would Hitler heil himself?

More somberly, Meinertzhagen claimed he met with Hitler in 1939 with a pistol in his pocket, and that he came with a spade of shooting Hitler on the spot—his own life be damned. He would recall this tale with a sigh in later years, bemoaning how he could have spared the world the most awful war in history. His dinner guests would coo and try to cheer him up. What a noble man.

You probably won’t be shocked to learn that Meinertzhagen never met Hitler, much less nearly shot him. But he told such tales with enough flair and melodrama that he became a celebrity in British high society.

One aristocrat was especially taken with him—Ian Fleming, the novelist who invented James Bond. In fact, Fleming based Bond in part on Meinertzhagen and his life—or at least, Meinertzhagen’s own version of his life.

After Meinertzhagen published a memoir in old age—full of tales of bravado—Fleming actually quit writing. He said no spy novel could compete with the exploits of the master.

In truth, after the 1920s, Meinertzhagen devoted most of his life to birding. That, not espionage, was his true passion. He loved to watch birds, to study birds, to track birds, and especially to steal them.

Like John James Audubon, Richard Meinertzhagen was both a prolific wildlife observer and a prolific wildlife killer. Over his life, Meinertzhagen amassed a collection of 25,000 bird skins, an obscene number. He shot at least half himself, and not always legally.

Whenever he visited an area where collecting was banned, he carried a special walking stick with a small gun concealed inside. That way, he could shoot any choice specimens on the sly.

As for the other half of his 25,000 birds, he bought the bulk of them. The rest, he stole.

He stole them from museums all over the world—Paris, Leningrad, New York. But his prime target was the Natural History Museum in London. He usually showed up in the Bird Room there around noon, when half of the staff was at lunch and there were fewer eyes to watch him. He’d request a box with maybe eight birds inside and take great pains to examine them. Then he’d slip one into his coat, say cheerio, and stroll out.

Given his background as a spy, he got away with it more often than not. But not always. Once, a clerk at the Museum caught him with nine birds stuffed into his briefcase.

He tried lying his way out. He said that a former curator there used to let him take specimens home to study them. Besides, he said, I’m Richard Meinertzhagen. I’m a gentleman and I’ll of course return them. The museum didn’t buy it and banned him from the Bird Room.

But a wealthy friend of his, a Rothschild, got him reinstated a year later at which point, Meinertzhagen resumed stealing specimens. Over the decades, he got caught several more times, and the Museum called in Scotland Yard twice. Both cases nearly went to trial. But the Museum always dropped the charges and reinstated him. Later, Meinertzhagen even got his own key to the Museum.

So why did the Museum tolerate him? In part, because the directors belonged to the same upper-class Old Boys’ Club that he did. They protected their own. There was also the typical British terror of fuss or scandal. Better to hush things up.

The main reason, though, was the 25,000 specimens Meinertzhagen owned. The Museum coveted them as a donation after he died and didn’t want to anger him. They figured that if he stole a few here and there—well, they would get them back eventually. And their deferential approach worked. When Meinertzhagen died, they secured the collection.

What the museum didn’t realize was that Meinertzhagen had not just been stealing the birds. He’d been changing the tags on them—the labels tied around the birds’ legs. These labels list where the bird was collected and when, the day and month. This information is vital for ornithologists. It reveals birds’ habitats and what their plumage looks like at different times of year. It also helps track migrations and determine how abundant a species is.

Meinertzhagen was an expert on bird migrations. And he was changing the labels on specimens to forge evidence for his pet theories about the migrations of certain species. This is a grave scientific sin—a massive betrayal of the field. Also, imagine the hubris here—trying to make the natural world bend to your will!

But to get away with this crime, Meinertzhagen had to do more than just change the labels. He also had to redo the preparations of the birds, to mask the evidence of theft.

To ready a bird for a museum in the 1900s, preparers followed the same basic steps. First, they sliced open the tissue-paper-thin skin around the belly and rolled the bird skin inside out like a sock. At this point, they discarded the guts, and most of the bones. They sopped up any blood or fluid with cornmeal. Then they used a dowel and cotton balls to make a dummy mount for the bird. Finally, they stretched the skin over the dummy and sewed the bird up.

Now, these were not like the birds you might see in a front-end museum display—birds with their wings spread wide, assuming dramatic poses. Backroom museum specimens are stiff and lifeless, with the wings tucked into the side. Most don’t even have eyes. They’re strictly for ornithologists to study the features of birds.

But if all bird-preparers followed the same basic steps, the details differed, because each preparer had their own style. In fact, a trained eye can tell one preparer’s technique from another’s at a glance, as easily as you can distinguish between two people’s handwriting.

This was especially true in previous centuries, when many preparers were self-taught. They also usually prepared specimens in remote places—forests or jungles or tundras, where they made do with whatever materials were on hand.

Instead of using a dowel to support the dummy, some used matchsticks or bamboo. Instead of cotton, they might stuff the body with hemp or moss. Some preparers kept more bones inside than others. Some removed the brains by slicing open the thin skull, while others removed the brain through natural sinuses. Some preparers left birds with taut, flat bellies, while others left birds’s bellies bulging, like they’d just polished off Thanksgiving dinner. The stitching could vary widely as well.

Meinertzhagen’s specimens had their own quirks. He usually turned the bird’s head slightly, leaving it at an angle. He also crossed the legs and left the bodies under-stuffed. His birds looked like no one else’s.

So, whenever he stole a bird from a museum, Meinertzhagen had to transform it. He’d unstitch the bellies and redo everything according to his own preparation methods, to hide his crimes.

As a former spy, and a longtime bird-skinner, Meinertzhagen was pretty good about covering his tracks.

But not perfect.

A dogged Irish biologist soon exposed his ploy about changing the labels on redpolls from France to England.

And as we’ll hear next week, Pamela Rasmussen at the Smithsonian would pick up that thread, and soon unravel the entire tapestry of Richard Meinertzhagen’s many, many scientific crimes.