The work of Richard Meinertzhagen helped convince biologists that the forest owlet of India had gone extinct. For decades, everyone believed that the only thing remaining of its existence were stuffed specimens in museums. But after Meinertzhagen’s fraud was exposed, ornithologist Pamela Rasmussen grew obsessed with finding out whether it just might still be alive.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

This is part two of a two-part series. If you missed part one, please start there.

One day in 1872, an Irish customs officer working in India decided to play hooky from work. Instead, Officer William Blewitt went hunting. And before long—bang—he bagged an owl.

Blewitt was thrilled. Collectors in England paid big money for birds from India, especially owls. And this one was lovely. But when Blewitt sent the bird to a naturalist, he got an unwelcomed surprise.

Blewitt thought he’d shot a species called the Spotted Owlet. They’re around ten inches tall, with grey-brown backs and wings and a fluffy white undercarriage. They also have yellow eyes and spots on their heads.

But the naturalist told him that this owl was different. Its head lacked spots, and it had fuller feathers on the neck and legs. It also had a larger bill and massive claws for crushing prey, with toes as thick as children’s fingers. The naturalist congratulated Blewitt—he had discovered a species new to science. He proposed using Blewitt’s name in the official Latin designation.

The news horrified Blewitt. In writing the species up, the naturalist needed to describe where and when it had been collected. If Blewitt’s boss saw that, he would realize Blewitt had played hooky and fire him.

So Blewitt lied. He claimed his brother had shot the owlet, not him. That way, he kept his job but also got to keep the family name in the bird’s name. A win-win.

The species Blewitt collected is now called the Forest Owlet. Over the next dozen years, six more specimens turned up in India, including some from a British army officer named James Davidson. Remember that name.

But when they looked into where the Forest Owlet lived, biologists noticed something. They’d all been collected in two small teakwood forests that sat 550 miles apart. That’s strange. Usually, birds either live in one small area, or they extend over a wide range. But two isolated pockets? It was unheard of.

Unfortunately, no other Forest Owlets turned up for decades. So, the mystery over its range remained unresolved.

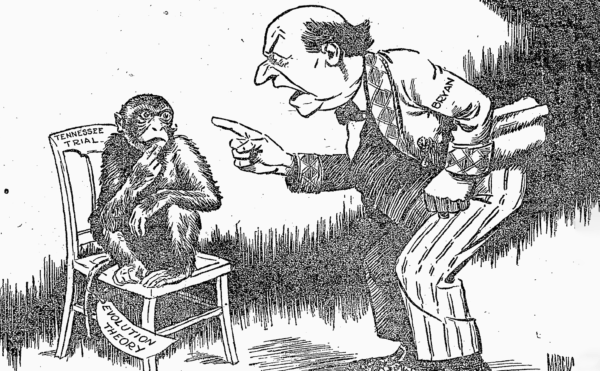

At last, another one emerged in 1961. Not in the wild, but in the private collection of Richard Meinertzhagen, the posh British ornithologist with a penchant for stealing birds from museums. And in finding the specimen, Meinertzhagen announced that he had solved the mystery of the Forest Owlet’s range.

He was lying. And his tangle of lies would plunge ornithologists into an even deeper mystery about the Forest Owlet. Had it been wiped out? Or was there still a chance to save this lovely bird from extinction?

From the Science History Institute, this is Sam Kean and The Disappearing Spoon, a topsy-turvy science history podcast where footnotes become the real story.

In 1961, Richard Meinertzhagen announced that he’d snagged the Forest Owlet in his collection 46 years earlier. He simply hadn’t recognized it then, since it looked a lot like the Spotted Owlet.

Finding any Forest Owlet was a big deal: by that point, none had been seen in the wild since 1884. Furthermore, Meinertzhagen announced that he’d shot it in what’s now the state of Gujarat, near the Arabian sea in western India.

This excited ornithologists. Again, naturalists knew of only two spots where the owlet existed. Meinertzhagen’s report now extended its range to a different habitat. It confirmed their suspicion that the Forest Owlet, while rare, extended over a broad area.

So, ornithologists decided to track the owl down. Several well-funded expeditions scoured its hypothetical range in the 1960s and 1970s. But while they found plenty of Spotted Owlets, no sign of the Forest Owlet ever emerged.

Depressingly, in 1972, they concluded that the owlet had gone extinct. All that remained of its existence were the stuffed specimens in museums.

That was the state of things when Pamela Rasmussen began compiling her field guide on the birds of India in the 1990s. Field guides focus on living birds, so initially Rasmussen ignored the Forest Owlet. She was far more worried about the 14 species of birds where Meinertzhagen was the only source for their presence in India—a fear triggered when she read an article about Meinertzhagen’s fraudulent science.

A few weeks later, she visited a facility outside London where Meinertzhagen’s collection was kept. She got specimens from those 14 species and examined their preparation styles—the quirks that distinguish one specimen-preparer from another.

At a glance, the birds all seemed to have been prepared by the same person. But upon closer examination, she found signs of tampering to cover up the telltale signs of other preparers. It became clear that all 14 birds had been prepared differently, by different people.

She also checked each specimen against the Natural History Museum’s records. Then she tracked down the ornithologists from whom Meinertzhagen had stolen each bird. In the end, none of the 14 species checked out. They’d been collected in Siberia, China, Mongolia. But not India.

On a whim, Rasmussen also examined Meinertzhagen’s Forest Owlet—the one he claimed he’d collected in 1914. And she found damning evidence that he had stolen it from the British army officer James Davidson.

What was the giveaway? For one thing, Rasmussen saw that the owlet’s abdomen was loosely stitched together. When specimens are fresh, you can stitch them shut tightly, because the skin still stretches. After it dries, skin turns brittle. Loose stitching is therefore a red flag that someone has reworked a specimen.

Rasmussen noticed other clues, too. Davidson tended to stretch the neck of his specimens, like a giraffe. And on the owlet Meinertzhagen supposedly collected, the neck had been folded to shorten it. Someone was trying to mask Davidson’s handiwork.

Davidson also stuffed his birds’ wings with cotton, which most preparers do not do. The wings of Meinertzhagen’s owlet were not stuffed. But when Rasmussen gently sliced its wing open, she found a tiny, overlooked lump of cotton in the very tip. It was greasy and yellow from the oils it absorbed from the bird’s skin.

Rasmussen then got hold of one of Davidson’s authentic specimens. She removed a bit of yellow cotton from its wing. She sent both bits to an FBI crime lab to analyze them. The lab quickly got back to her. The fibers were a perfect match.

As a final bit of detective work, Rasmussen checked Meinertzhagen’s diaries for the month he supposedly collected his owlet. They revealed that he had never even left Mumbai that month. He couldn’t. World War I had just broken out, and he was too swamped with intelligence work to go hunting.

In a criminal trial, a jury would have convicted Meinertzhagen in about five minutes. He was guilty, guilty, guilty of stealing the owlet from Davidson.

As mentioned last week, Meinertzhagen once claimed that Lawrence of Arabia confessed something to him: that he, Lawrence, was a fraud and would be “found out” someday. In reality, that was probably Meinertzhagen’s guilty conscience talking.

At this point, Rasmussen was feeling pleased with herself. She’d exposed Meinertzhagen; she’d restored credit to less-renowned ornithologists; and she’d avoided several potentially embarrassing mistakes in her field guide.

But one thing continued to nag her. Again, Meinertzhagen’s supposed 1914 owlet appeared in a different region compared to the authentic ones. And in the 1960s, when Meinertzhagen’s reputation was still stellar, that one data point had convinced biologists that the owlet lived across a wide range.

But without Meinertzhagen’s data point, that theory crumbled. And when Rasmussen checked into the expeditions from the 1960s and 1970s to find the owlets, she realized that none of them had checked the actual locations where Davidson and others had collected their specimens.

Rasmussen was dumbfounded at the implication. The species had already been declared extinct. But was it? There was only one way to find out. She would have to go to India.

Rasmussen knew that the hunt for the Forest Owlet would be difficult. The bird had been recorded in just two small patches of teakwood forest. They sat 550 miles apart. Heavy logging and deforestation had decimated those patches since 1884 and might have pushed the bird elsewhere.

Equally bad, her team did not know what the owlet sounded like. In a forest, you can hear birds from much farther away than you can see them. Plus, ornithologists searching for rare species often lure the birds by playing recordings of their calls. That was not an option here.

In fact, the more Rasmussen thought about it, the more her trip seemed hopeless. In her words, she figured she had “a higher chance of being killed in a car wreck than of finding this bird.” She added, “and the closer it got to the time to go, the more I felt it was silly to even try.”

The only clue to help her was something James Davidson had said. He had found his owlets perched atop bare, leafless trees around dawn and dusk. So, her team would concentrate their efforts at those times.

The expedition began in November 1997. Rasmussen’s team started in Raipur in eastern India. They spent day after day tramping through the woods there, guessing at different calls that the owlets might make. They squeaked and squawked. They trilled and hooted. Nothing worked—no owlets appeared.

After nine empty days, they left in low spirits. They drove 550 miles to their second target area, the Taloda Nature Reserve in western India. Upon arrival, their shoulders sagged in disappointment. The reserve was sparse, and it lacked a solid canopy—not promising for a so-called Forest Owlet.

They nevertheless resumed tramping about and hooting and trilling, hoping one would turn up. Instead, more empty days passed.

November 25th was their second-to-last day. A determined Rasmussen shook her crew awake at 4am to head out. They spent four hours trudging around. By 8:30, she gave up. The day was already hot, too hot for most birds to be active. They would regroup and try again at dusk.

Rasmussen opened a water bottle and turned for home. At that moment, a man in her crew stopped in his tracks. Then, quietly, he said, “Look at that owl.”

When her colleague said, “Look at that owl,” Pamela Rasmussen turned—and dropped her water bottle in shock.

The bird was sitting in a tree, not far off. She took a long second to convince herself that it was not a Spotted Owlet—the two species do look alike.

But she saw no spots. Plus, the claws were too thick, and its neck and leg feathers were too fluffy. She was staring at the first recorded Forest Owlet in 113 years.

But would anyone believe her? Recall the episode I did a few seasons ago on the ivory-billed woodpecker. Plenty of people have claimed to see that bird. But without a specimen or clear pictures, bird sightings do not count for much.

So, upon seeing the Forest Owlet, Rasmussen wanted to fling her pack down and rip her camera out. But sudden movements could startle the bird. So, she proceeded as slowly as she could.

Her tactic didn’t work. She heard a fluttering of wings and looked up. To her horror, the bird was taking flight. Her heart leapt into her throat. Would she ever see one again?

But she need not have worried. The owlet was not flying away. If anything, it was flying closer—it wanted a better look at her. It landed on a branch and then just sat there, checking her out—cocking its head like birds do.

Rasmussen’s hands were shaking as she aimed her video camera. But she got thirty full minutes of footage, as did her colleagues. They probably would have filmed all day, except another bird finally started harassing the owlet, and it flew off.

The next day, they found a second owlet at 8am, at a spot 200 yards from the first. They even captured its call this time. A sort of monkey war hoot. Listen…

And with that, with both video and audio evidence, they officially resurrected the Forest Owlet from extinction.

Rasmussen and her team published a paper about the discovery, to great acclaim. But perhaps the most important outcome of her work was the long-overdue exposure of Richard Meinertzhagen.

Meinertzhagen’s fieldwork ended in 1960. That year, when he was 82, a dog in a park tripped him, and he fell and broke his hip. He was essentially bedridden until he died seven years later. At that time, his legacy seemed secure—a celebrated ornithologist, a spy so daring he inspired James Bond. What a life.

But after Rasmussen and others exposed his frauds, historians began to scrutinize Meinertzhagen’s biography with more skeptical eyes. They found that he’d invented most of his spy exploits.

His personal life suddenly looked ugly as well. I’ve put together a bonus episode about this at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. In short, there’s now good evidence that Meinertzhagen either murdered his wife in cold blood or killed her in a duel. He might have done so for two reasons. One, she threatened to expose his scientific fraud. In addition, Meinertzhagen had developed a suspiciously close relationship with his fifteen-year-old cousin. All that at patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

As with John James Audubon, a few clear-eyed colleagues in the mid-1900s had always suspected Meinertzhagen was not on the up and up. One colleague scoffed at Meinertzhagen’s quote, “miraculous ability to stop very briefly somewhere but nevertheless collect important material.” And in retrospect, some of Meinertzhagen’s collecting anecdotes seem ludicrous. Like the time in Tibet he supposedly snatched a rare bird off the back of a yak.

After his death, when Meinertzhagen’s 25,000 bird specimens arrived at the Natural History Museum in London, one curator there startled his colleagues by proposing that they burn the whole thing. He’d never trusted Meinertzhagen, and he thought the stolen specimens and forged location tags made the whole collection useless.

In the end, they did not burn the birds. And good thing: the forensic work of Rasmussen and others has helped restore the collection’s accuracy.

But the damage has been real. Ornithologists had mapped the range and migratory routes of several species based in part on Meinertzhagen’s data. This included some endangered species. All those maps suddenly needed rewriting, at gigantic cost. Naturalists had to scramble to figure out where endangered birds really lived.

Overall, Meinertzhagen’s deceptions have been called “the greatest ornithological fraud ever.” Personally, I’m not sure it beats out Audubon’s Bird of Washington scam in terms of historical importance. After all, the Bird of Washington launched the career of the most famous ornithologist in history. But in terms of sheer scale, there’s no question—Meinertzhagen is champ.

His misdeeds with the Forest Owlet deserve special criticism. His claims about the bird’s range forced ornithologists to waste years looking in the wrong places, and to do so at a critical time—a time when the owlet’s real home was being logged for wood and was all but wiped out. Had he not deceived the world, we would have had decades longer to preserve and save the bird.

Because sadly, despite the surge of hope from the rediscovery, the Forest Owlet remains endangered today. There are fewer than 1,000 in the wild. Now, we cannot lay all the blame on Richard Meinertzhagen here. Humans have driven a lot of species to the brink of extinction. But even a super-sleuth like Pamela Rasmussen cannot undo all the damage he has done to the animals he claimed to love.