At around nine months old, wandering albatross chicks leave their nests and take to the skies for the first time. Five years may pass before they again set foot on solid ground.

The young albatrosses navigate the Southern Ocean with a specialized sense of smell, locating squid and other prey up to 12 miles away. Their ability to hear infrasound may help guide their flight paths: the ocean’s low-frequency growls can travel thousands of miles, announcing large crashing waves and accompanying strong winds. Wanderers circumnavigate Antarctica two to three times a year on these winds, covering roughly 75,000 miles. By weaving between fast and slow layers, they stay aloft with barely a wingbeat.

Over the course of a 50-year lifespan, one may travel 5.3 million miles—the equivalent of 11 trips to the moon and back. But the drive to mate means that, from the age of about 10 onward, every other year adult albatrosses will navigate back to the pinpricks of land where they were born to reunite with their mates and raise a single chick. For many of the world’s wandering albatrosses, that place is Marion Island.

Located halfway between South Africa and Antarctica, Marion Island is not a stereotypical island paradise: it is windswept, cold, and constantly wet. The island is the summit of a huge underwater shield volcano rising 3 miles from the seabed. Marion’s Mascarin Peak coughed up gas and lava stones as recently as 2004. Usually, though, the island’s slopes are dusted with snow. Further down, where the albatrosses nest, marshy plains ripple with cushions, ferns, and other low-lying plants that can survive the Roaring Forties, the notorious westerly winds. To the northeast, Marion’s sister island, the tiny, cliff-edged Prince Edward Island, is visible on the horizon.

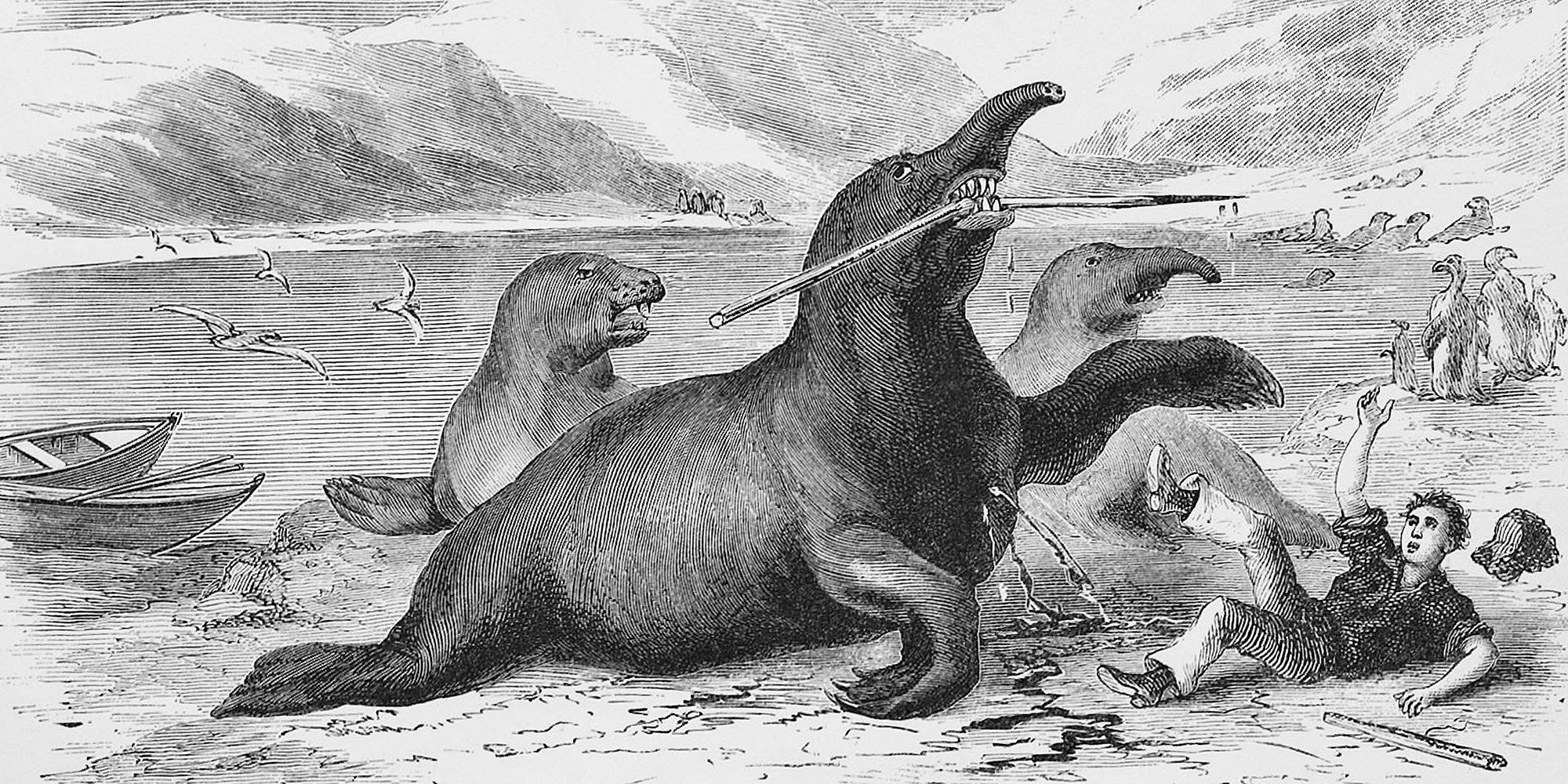

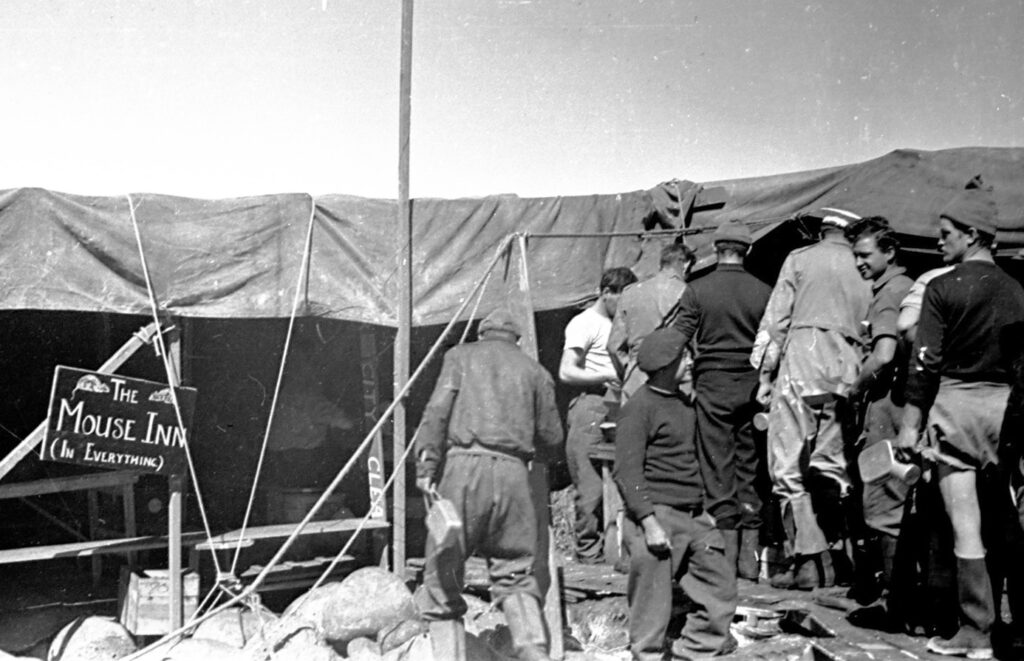

Despite—or because of—their desolation, these islands have long been the breeding sites of millions of rare seabirds: parades of penguins, fleets of burrowing petrels, and, of course, rookeries of wandering albatrosses. Then, in the early 19th century, humans disembarked, bringing with them an unlikely, lurking predator.

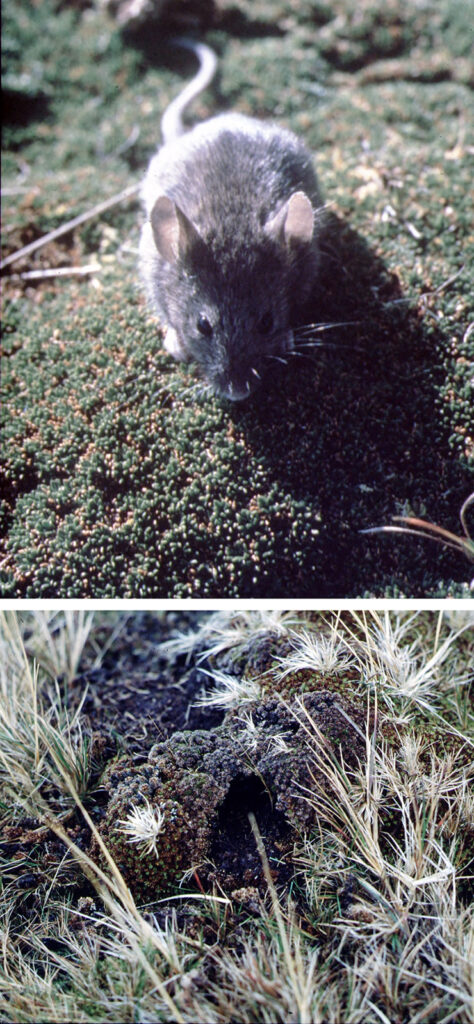

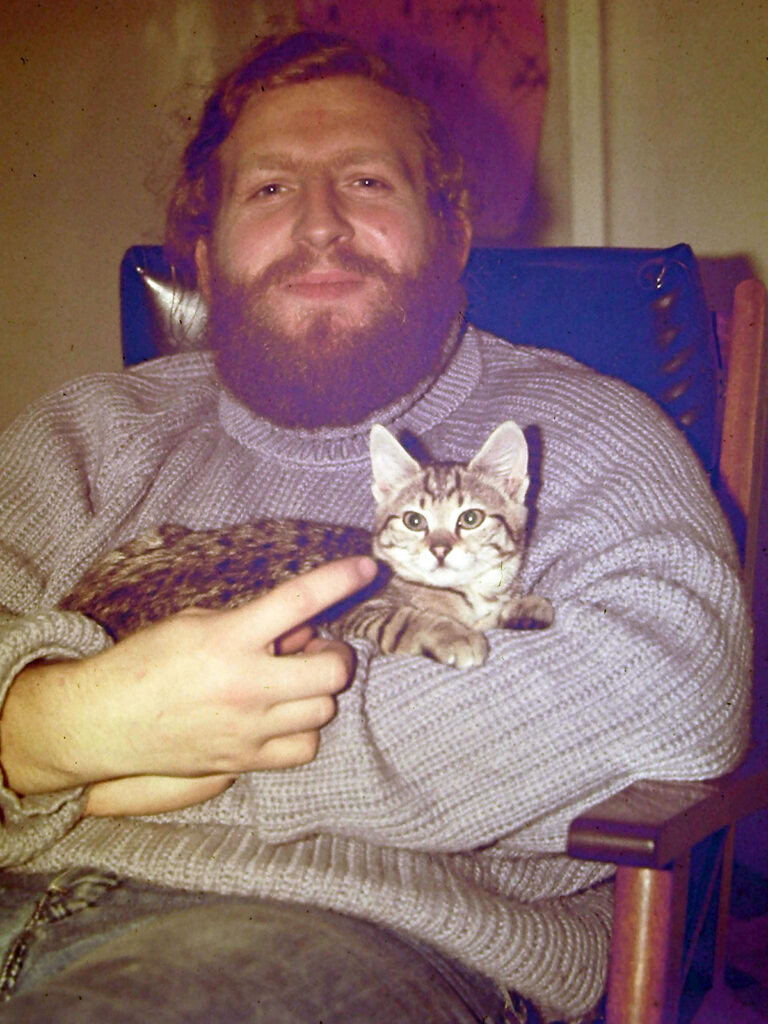

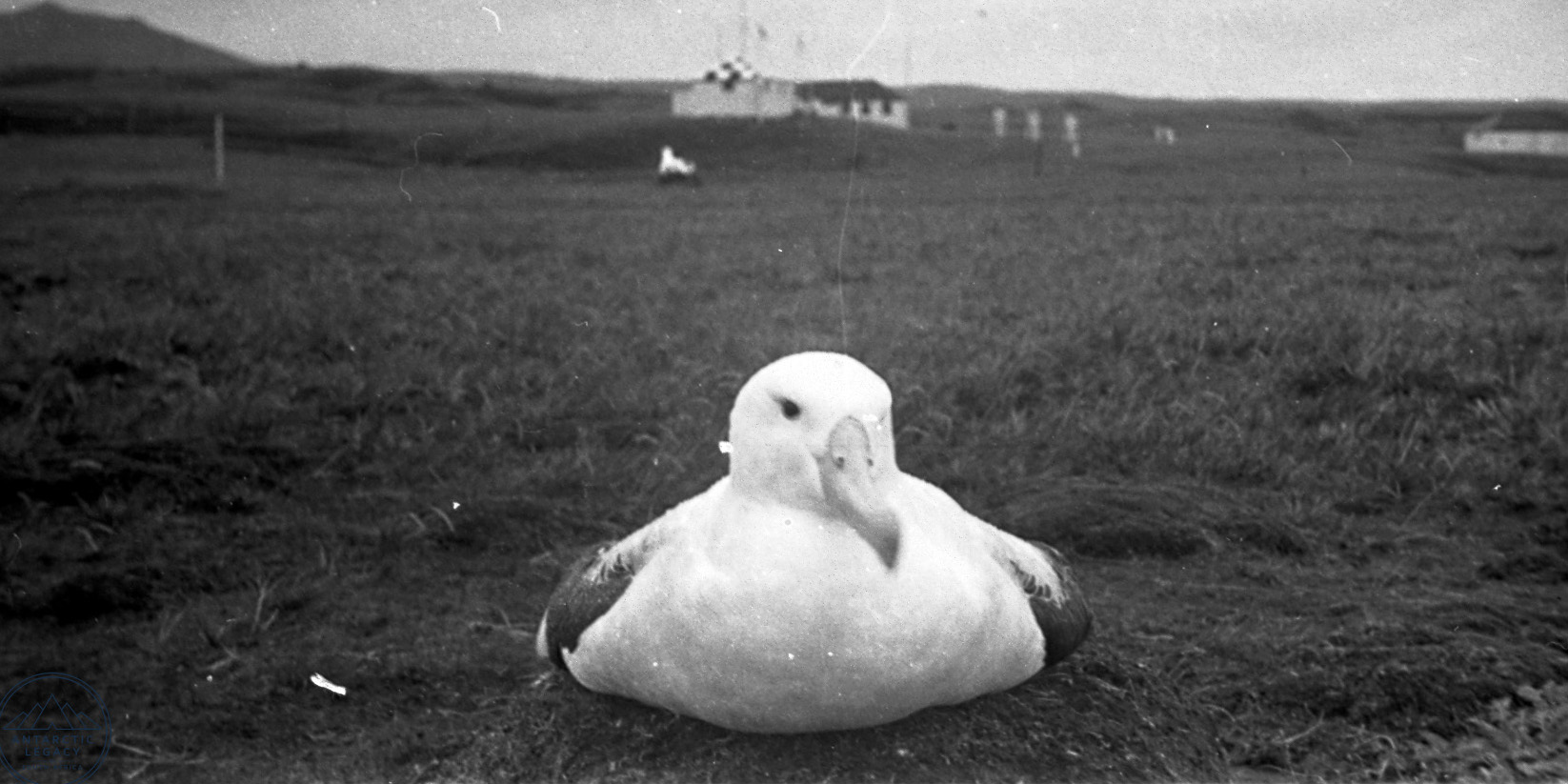

Some 200 years after its accidental arrival, the tiny house mouse has discovered what cats and men had long known: for all their aptitude at sea, pelagic birds make for easy prey. In 2019, photographer Thomas Peschak visited Marion Island to document the increasingly brazen mouse attacks. “In this landscape of black and green and grey, there is this red that pops out at you all of a sudden,” he recounted on the National Geographic podcast Overheard. “You come around this boulder, and you are literally looking at a bird that has been scalped.”

Since Peschak’s visit, bird casualties have mounted. If left uncontrolled, experts predict the mice could drive 18 of the islands’ 28 bird species to local extinction, some within the next three decades. That would wipe out a third of the global breeding population of wandering albatrosses and white-chinned petrels. Over time, the island itself would become ecologically unrecognizable. And so scientists and conservationists have hatched a plan to save the seabirds and restore Marion’s imperiled ecosystem.

Inspired by past eradication programs, South Africa’s Mouse-Free Marion Project aims to rid the island of mice once and for all. Standing in its way are turbulent sub-Antarctic weather conditions, 30,000 hectares of craggy mountains, boot-sucking bogs, and the harsh reality that success is guaranteed only if every last mouse is killed.