In the spring of 1937 Georg Bredig was forlorn.

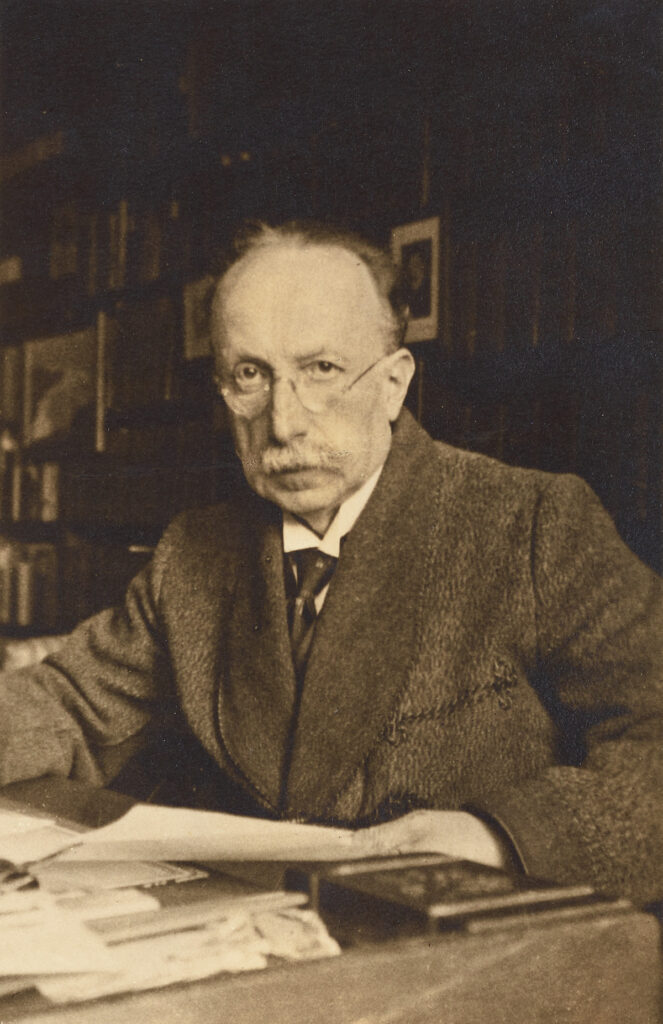

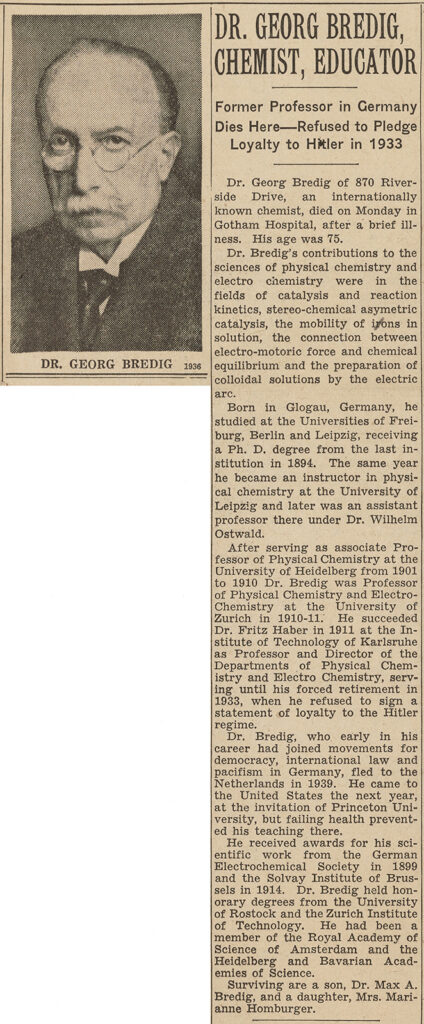

The chemist had watched with disbelief as the Third Reich and fervent antisemitism seized Germany. Though a revered figure in the field of physical chemistry, Bredig had spent the past four years in professional exile—forced to retire because of his Jewish heritage and refusal to pledge allegiance to Hitler.

Things had only become worse since he lost his job. The Nuremberg Race Laws, introduced in 1935, stripped German Jews of many civil rights, including the right to work, travel freely, access public services, and own property. Disenfranchised and robbed of his vocation, Bredig now turned his attention to his scientific legacy. He worried his life’s work would be the next destroyed by a fascist mob.

The burning of books by Jewish authors had been underway since 1933. Bredig’s former colleague Albert Einstein was among the first Jewish thinkers to have his works set ablaze publicly. Einstein immigrated to the United States and was followed by many other Jewish intellectuals.

Bredig refused to leave Germany, but he wasn’t oblivious to the perilousness of his position. He hurried to locate a haven for his “opera omnia,” as he had dubbed his library.

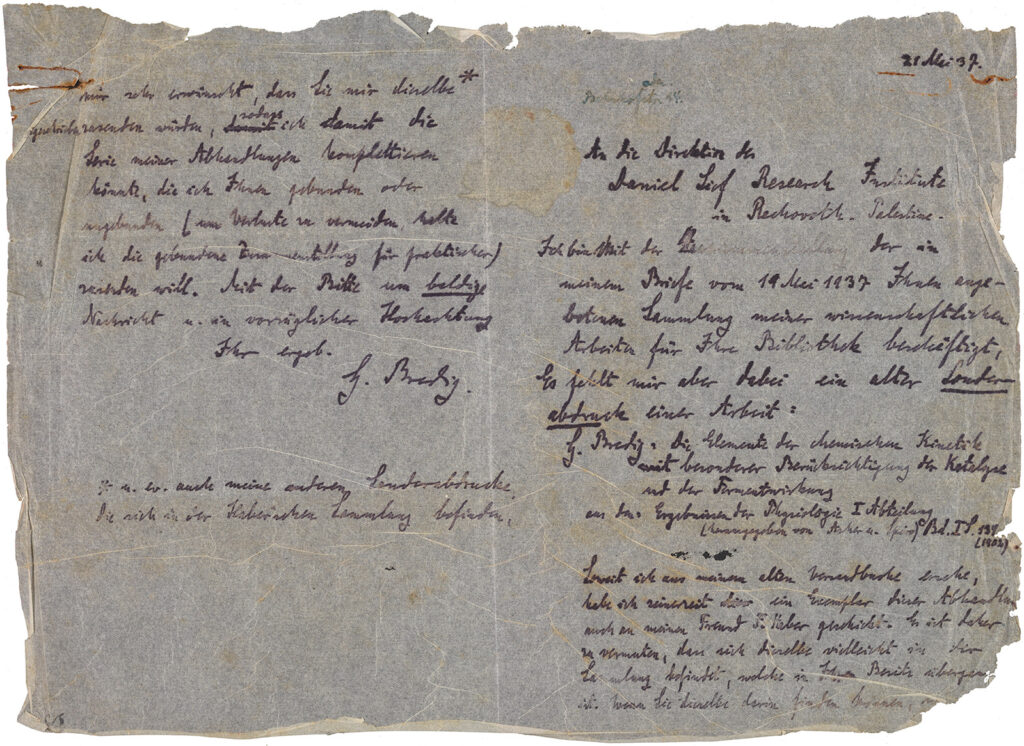

In May 1937 he wrote the Daniel Sieff Research Institute in Palestine. “I would like to send you a collection of all the scientific works and publications written by me and my colleagues in the various fields of physical chemistry, electrochemistry, biochemistry, and more specifically, catalysis,” the last being Bredig’s specialty. “If you are interested in this donation, please respond as soon as possible.” He closed the letter with the same plea: “Please respond as soon as possible.”

To Bredig’s relief, the institute accepted his offer. Yet it was a hollowed-out sort of relief.

When his friend Karl Freudenberg visited the following year, he found Bredig looking “infinitely lonely” as he stood before the empty shelves of his former library.

This nefarious world was only beginning to emerge when Salomon Julius Georg Bredig was born on October 1, 1868. Bredig was the first child of a middle-class, German-speaking family in Glogau, Lower Silesia, Prussia, in what is now western Poland.

From an early age, Bredig showed a gift for science, talents nurtured by his uncle Moritz Hollstein, a bookseller. Bredig studied natural sciences at the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin, where a key mentor, Wilhelm Will, introduced him to physical chemistry.

Russian chemist Mikhail Lomonosov had devised the term physical chemistry in the mid-18th century to describe how theories of physics could be used to study chemical processes, but its modern usage began in the late 19th century to describe work on kinetics, thermodynamics, and electrolytes.

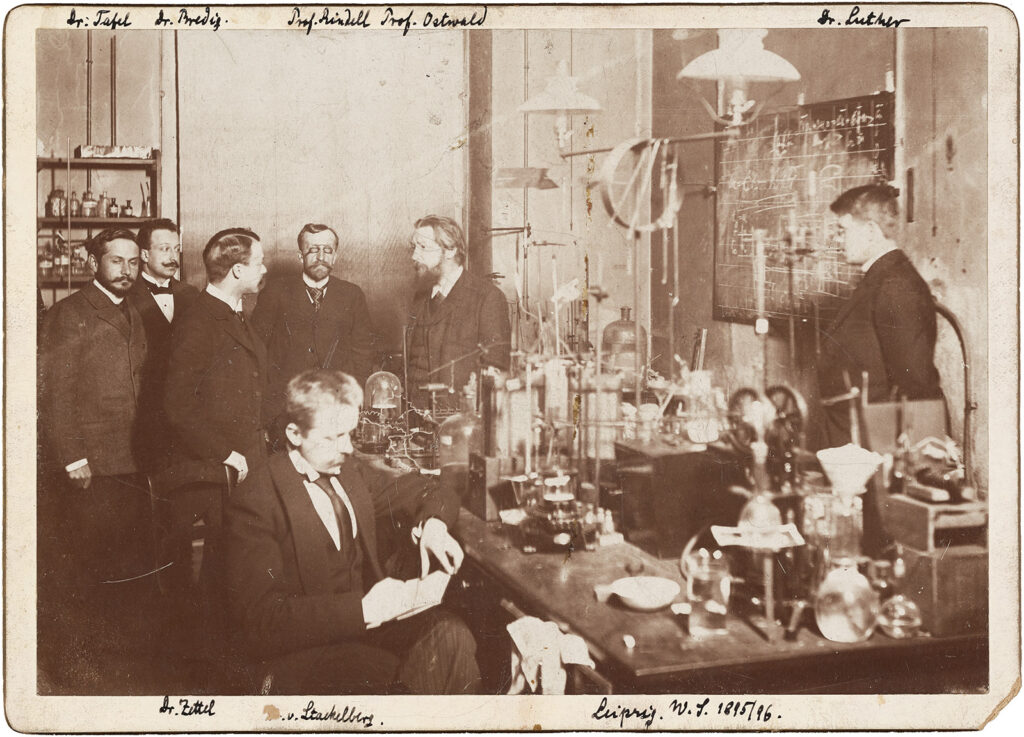

In 1887, during Bredig’s second year at university, Wilhelm Ostwald founded the Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie, the first scientific journal dedicated to physical chemistry. The journal’s first issue introduced Svante Arrhenius’s ion theory and Jacobus Henricus van’t Hoff’s work on osmotic theory. The dynamic intellectual interplay among this trio drew Bredig to the burgeoning field.

After graduating, Bredig joined Ostwald’s lab as a doctoral student at the University of Leipzig. The young chemist found himself at the vanguard of a new science in a thoroughly modern home. Ostwald’s institute had been inaugurated months earlier and immediately attracted scholars from around the world, including Arrhenius from Sweden, Walther Nernst from Prussia, and Yukichi Osaka from Japan. Bredig would maintain lifelong friendships with many of these colleagues, connections that would later prove vital.

Upon earning his doctorate in 1894, Bredig continued working for Ostwald while also distinguishing himself in the field of catalysis. Between 1898 and 1900 he invented and refined a novel technique, named Bredig’s arc method, for creating colloidal solutions of metals used as catalysts. The invention became chemists’ preferred method and earned Bredig wide recognition.

Chemist Nikolai Menshutkin wrote Bredig from St. Peterburg to praise his work on catalysis, from which, the Russian declared, “a new field has arisen . . . the scope of which has yet to be seen!” The success convinced Bredig to pursue a career in academia, and in 1901 he earned an appointment as the first professor of physical chemistry at the University of Heidelberg.

The University of Heidelberg’s medieval origins belied the campus’s intellectual atmosphere at the turn of the century. Bredig found both state-of-the-art scientific facilities and a spirit of liberalism among his colleagues. “Dynamic,” Arrhenius called it in an encouraging letter.

Bredig’s personal life was changing in big ways as well. Shortly after accepting the job, he married Rosa Fraenkel, and the couple had two children in short order: Max Albert in 1902 and Marianne in 1903.

Over the next decade Bredig led pioneering research on catalysis while branching into kinetics and electrochemistry. He mirrored Ostwald in attracting some of the field’s brightest young minds to his lab, including Kasimir Fajans and James McBain. Despite this success, the chemist yearned for change. The liberal atmosphere on campus suited Bredig, but relations among the faculty stifled him and left him feeling isolated and discontent. In 1910 he departed Heidelberg for the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, better known as ETH Zurich.

The appointment in Zurich was pleasant—he became acquainted with Albert Einstein and enjoyed the Swiss countryside with his young family—but a more prestigious opportunity at the Technical University of Karlsruhe pulled him away within a year.

It was an intimidating move. Bredig was taking over for Fritz Haber, the future Nobel Prize winner who had left the school to industrialize his famous nitrogen-fixing process with partner Carl Bosch. Bredig’s time in Karlsruhe got off to a promising start, but World War I ground his research to a halt.

The fighting had devastating consequences for universities across Europe. Laboratory research was cut off, with most science and technology work directed toward the battlefield. “It is pretty empty in the institute because many of my students and some of the employees are in the army, but I continue to hold lectures and still have an audience,” Bredig wrote to Arrhenius in February 1915.

The war also cut fissures through the scientific community.

Haber, for example, believed scientists were patriots first and foremost, and set to work building Germany’s chemical weapons arsenal. Bredig was of an entirely different mindset. As a devout pacifist, he rejected military research and, like Marie Curie, volunteered for the Red Cross.

The war ended, but supply shortages and administrative demands convinced Bredig to give up the lab for good. Instead, he devoted himself to teaching.

He was “very much the authoritative German professor,” remembered nuclear chemist and former student Elizabeth Rona. But “under his surface sternness and aloofness, Bredig was a warm and sensitive person devoted to his students’ welfare.”

While Arrhenius and other friends criticized Bredig for abandoning research, his commitment to teaching was rewarded, leading to his appointment as university rector for the 1922–1923 academic year. One of the duties of the position was to deliver the annual rector’s speech.

Bredig used the opportunity to address the political schisms and extremism that had swept Europe, and Germany in particular, after the war.

Bredig lamented the injustices of the Treaty of Versailles, labeling it a “Vampyrfrieden” (vampire’s peace) and a cruel compromise. Nevertheless, he argued for European unity, the path for peace, and free intellectual and scientific exchange in Europe. “One day, the great European statesman must and will create this ideal of the “United States of Europe,’” he declared. He made his case using science, asserting that the democratic principles of Greek antiquity are necessary for scientific progress while highlighting how international collaboration furthered the pioneering work of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, and Marie Curie in physics.

The speech reverberated beyond the university’s walls.

“I read your speech with great interest,” wrote one admirer. “It is an oasis in the desert when a university professor has the courage to take a stand against the catastrophic blindness of today’s youth and to advocate utilizing our nation’s resources, which are capable of demonstrating Germany’s sanctity and hope to the world. May your words reach the hearts of young people!”

Others in Bredig’s circle were more measured in their responses.

Arrhenius shared Bredig’s hope that Europe had recognized the fruitlessness of war, but also expressed pessimism about the prospects for unity and intellectualism on the continent. “How science will develop in Europe in the long run remains unclear to me. For the time being, we are approaching barbarianism,” he wrote.

Indeed, the speech’s liberal idealism and humanistic views placed Bredig on the radar of right-wing circles, especially the university’s antisemitic student union. When Bredig tried to fill a vacancy with a Jewish scientist, the organization told him in writing that hiring a “Semite” would be unacceptable. In a further sign of the darker times ahead in Germany, the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper disparaged him and labeled him a Jew.

Despite the professional tensions Bredig faced throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, his family life remained an oasis. As his children entered adulthood, Bredig relished the role of paternal mentor. In a 1927 letter Bredig thanked his son, Max, for chaperoning his sister on a sailing trip in Berlin and stressed the importance of familial duty.

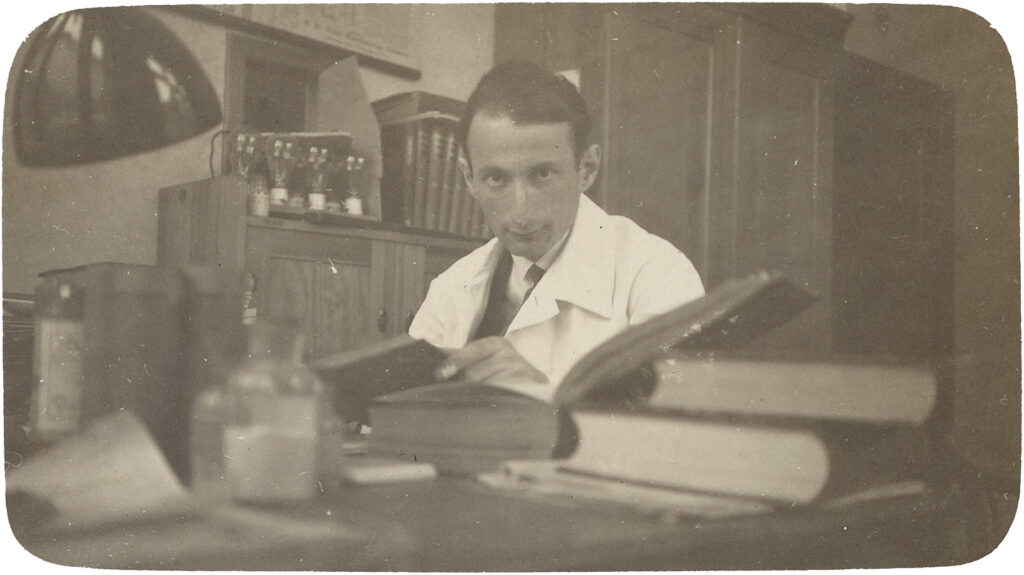

The father was also focused on the professional future of his son, who had likewise decided to become a chemist. Bredig tapped into his extensive network of former students and colleagues to help his son find work with Kasimir Fajans at the University of Munich and later at the Bavarian Nitrogen Works in Berlin.

Georg Bredig had seemed to achieve everything one could aspire to: a fruitful career, a joyful family life, and the success of his children. Yet antisemitism lingered in his thoughts. Bredig warned Max in 1927 to be aware of this bigotry and remain “useful,” “efficient,” and “indispensable” at work.

He was right to offer such caution.

Although Germany appeared to steady itself as the 1920s progressed, unrest and political extremism again intensified after the global stock market crash in October 1929. Hitler, who had struggled to rebuild the Nazi party after his failed Beer Hall Putsch and imprisonment in 1923, exploited widespread unemployment and instability. The Nazi ranks swelled, and by the summer of 1932 it was the largest party in Germany.

Germany’s conservative establishment tried to stem the Nazi threat by joining forces with them. In January 1933 President Paul von Hindenburg reluctantly appointed Hitler chancellor of a coalition government. The ploy’s folly soon became apparent.

In February 1933 Germany’s parliament building, the Reichstag, burned down. Nazi leadership pounced, casting the fire as a Communist assault on the republic. The next day Nazi leaders cowed their conservative partners into enacting the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended a wide range of civil rights and allowed Nazis to suppress their political opponents. Within a month Hitler bullied and bribed the Enabling Act of 1933 through parliament. The legislation gave Hitler and his cabinet the right to create laws independently, allowing him to seize authoritarian rule of the country.

In short order, Hitler and the National Socialists began Gleichschaltung, the process of controlling all facets of German life.

The first indignity of Gleichschaltung imposed on Georg Bredig was his forced retirement from the Technical University of Karlsruhe. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Service, passed in April 1933, forbade Jews from occupying civil service posts. Bredig lost his job after one of his antisemitic colleagues personally complained about him to the ministry that oversaw the employment of university faculty.

Worse, Rosa Bredig died that same year after a brief illness. Bredig’s anguish was profound. When Max forgot to commemorate his mother’s memory on the third anniversary of her death, Bredig was furious. “Today, on the anniversary of your mother’s death, I didn’t receive a letter of condolence from you,” Bredig scolded. “Other people remembered.”

Although many of Bredig’s contemporaries left Germany soon after losing their university positions, Bredig remained. In a declaration from September 1933 to a Third Reich court official, he wrote,

As more Nuremberg laws were passed, further indignities followed. Bredig’s documentation was stamped with a “J,” which restricted his travel abroad. His phone calls were tapped, and he was forced to declare his financial assets.

His children, of course, suffered similar humiliations. When Nazi officials instructed German companies to “aryanize” by terminating employees of Jewish descent, Max was pressured to resign from the Bavarian Nitrogen Works in 1937. Marianne was refused membership in a seamstress guild. Although the Bredig family’s wealth offered some protection from the worst of the injustices, Georg, now almost 70 years old, was devastated by the hostility.

“All of this is hardly bearable for me, but I still try to maintain my composure in spite of all the violence,” Bredig confessed to Max in a letter from September 1936.

Yet he still wasn’t ready to abandon Germany, although he encouraged his son to accept a fellowship with Fajans at the University of Michigan in 1937. Bredig also began taking measures to safeguard his intellectual legacy. Parts of his library went to the Daniel Sieff Research Institute; he sent other items to colleagues abroad. He shipped his most important works to Max, who was growing to enjoy life in the United States and searching for a permanent job.

“I’m doing well. The job search continues,” Max wrote on November 10, 1938. “After the Republican primary elections, there should supposedly be more prospects.” Max tragically did not yet know prospects for his family had become much more tenuous. Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, had transpired the day before.

Late in the evening of November 9, after the assassination of a German embassy official in Paris by a Polish Jewish youth, the Third Reich unleashed a series of violent antisemitic pogroms across Germany and its annexed territories. In Karlsruhe, Bredig and his son-in-law, Viktor Homburger, were arrested. Bredig was locked in a cold courtyard overnight; Viktor was deported and interned briefly at the Dachau concentration camp. He was released only after stating his plans to emigrate and signing over the rights to his family bank, which was subsequently liquidated by the Nazis.

Georg Bredig knew that he and his family needed to leave Germany—their lives depended on it.

“We are healthy, but, as you can imagine, we are very worried,” Bredig wrote to Max soon after.

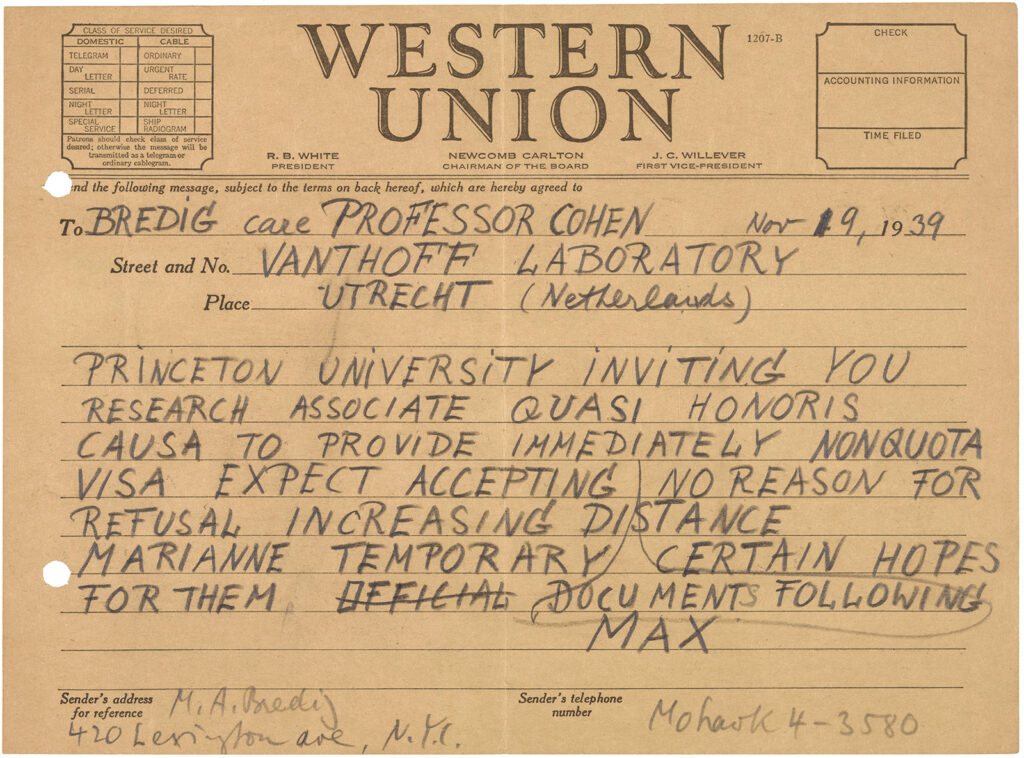

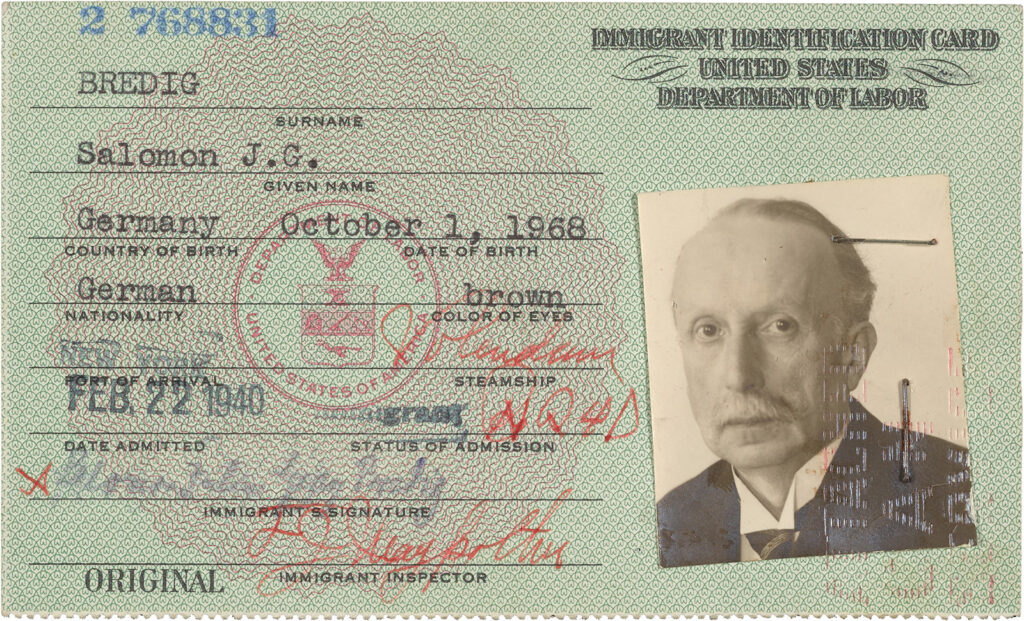

Over the next year Marianne and Viktor Homburger sent their children to England on a Kindertransport and futilely applied for visas to emigrate. Bredig fled Germany and temporarily found refuge with his friend Ernst Cohen in the Netherlands while he waited for his son’s plans to bring him to the United States to materialize. Success arrived in late 1939 when Max, who was by this point working at the Vanadium Corporation of America in New York, secured a lectureship for his father at Princeton University with the help of his father’s former colleagues and students. An elated Bredig accepted the offer in December 1939 in a letter to Princeton’s president, Harold Willis Dodds: “I venture to convey my heartiest thanks to you and the Department of Chemistry for the great honor and kindness bestowed upon me by the invitation to come to your illustrious university. Be sure that I shall endeavour to be worthy of it.”

Bredig departed the Netherlands for New York in January 1940. Although he was fortunate to escape the most harrowing events of the Holocaust, his daughter and son-in-law were not as fortunate. In October 1940 Marianne and Viktor were among the thousands of Jews in Baden, Germany, arrested and deported to Vichy France. The couple spent nine months in the Gurs concentration camp before Max secured their freedom. Again, Bredig’s connections saved the day.

“We would never be here if Professor [Alfred] Reis and his cousin Buchwald hadn’t supported us,” Marianne wrote from Lisbon after their release in 1941. “Your good spirits are everywhere, Father.” The Bredigs soon returned the favor, helping Reis immigrate to the United States the same year.

Georg Bredig survived Nazi Germany, but he never escaped the Holocaust. The years of denigration he experienced shattered him emotionally and physically.

“The last few weeks that we spent together in Bleicherode were very difficult,” Marianne wrote in 1940, before her deportation. “Every evening, he didn’t go to bed without saying: ‘Oh if only I didn’t have to wake up.’ Sometimes, I think that he should have stayed with us among his books and in his familiar surroundings.”

Bredig ultimately never worked at Princeton. He lived with Max in New York until he died in 1944. Upon Georg Bredig’s death, letters of condolence to his children revealed the impact Bredig had made on the world of chemistry and the sweep of the personal and professional relationships he had maintained.

“Over the years, I followed the immense, albeit quiet progress of his research with admiration,” wrote chemist Ernst Berl. “He accomplished more in his career than most capable scientists. His memory will live on in my heart, and in the hearts of many other friends that he made through his warmth and sincerity.”

In the latter part of his life, Georg Bredig experienced grievous intellectual and emotional chasms. Yet the country where he came of age and prospered was always antisemitic. Bredig recognized this fact early on and attempted to overcome it with assimilation and diligence. When judged at a distance, this strategy appeared to work for much of his life. The world of science in Germany seemed protected against outright prejudice against Jewish scientists before the rise of National Socialism showed it wasn’t.

Bredig’s adversities align with the post-Holocaust analysis of Chaim Weizmann, a Russian biochemist who became the first president of Israel. While Weizmann believed in the ability of science to solve serious problems, as Bredig had envisaged in his rector’s speech, Weizmann also lamented the “ignoble servility” Jewish scientists experienced in Europe. A lifelong Zionist, Weizmann sought solutions for antisemitism in a Jewish homeland within the Mandate of Palestine. Yet before Israel’s establishment on this territory in 1948, that was not possible for most Jewish refugees trying to flee Europe in the 1930s and 1940s.

Instead, as Jewish scientists raced to find refuge from Nazism elsewhere in the world, the Mandate of Palestine under Weizmann’s helm became a haven for their legacies. In 1934, Weizmann founded the Daniel Sieff Research Institute in Reḥovot to both further the work of Jewish scientists and rescue German Jewish property, including parts of Georg Bredig’s library. This act of intellectual salvation ensured that the contributions of Bredig and many other intellectuals were not wiped away entirely.

The reclamation of these lives continues.