Los Cedros, Ecuador, October 2022. A hexagonal, open-sided hut glows in the darkness of thick forest. An insect cacophony blazes from the trees beyond. But inside, beneath two bare, moth-engulfed bulbs, hush falls. “Friends of this forest,” begins coffee farmer and anti-mining activist José Cueva. “We would like to tell you something of the history of resistance in the Intag Valley.”

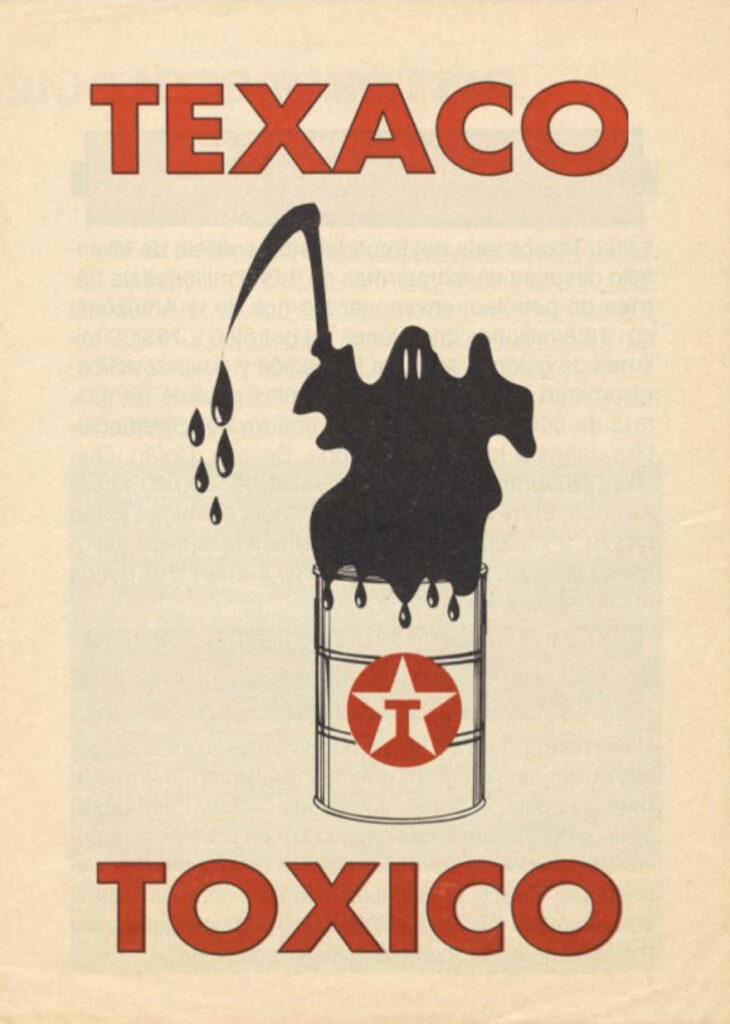

Cueva and his partner, Monse Vásquez, speak into the night of the intergenerational battle between extractivismo de muerte (death extractivism) and anti-mining resistance in this place. It’s a story of violence and solidarity, futility and hope.

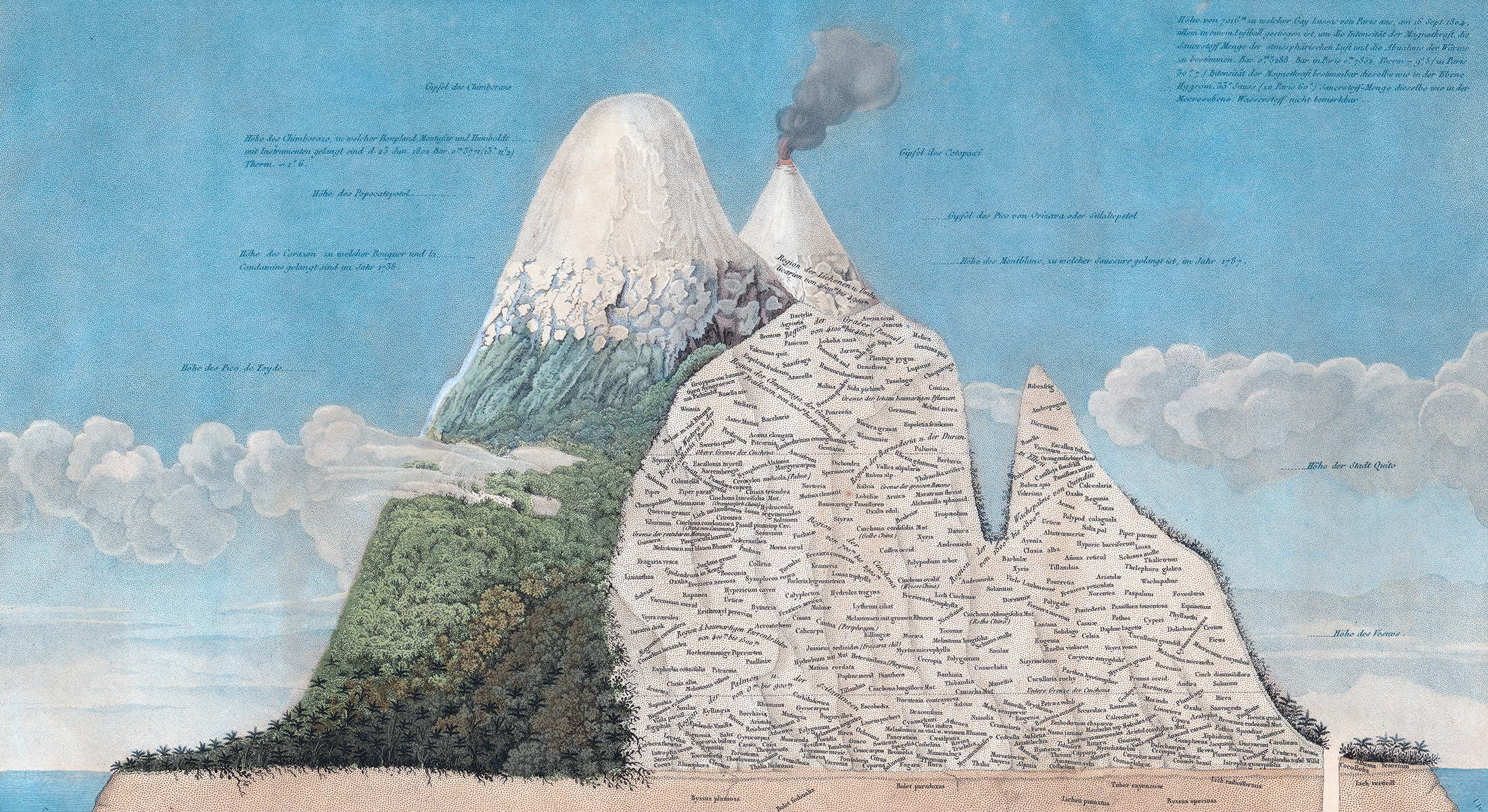

The surrounding forest is Los Cedros (The Cedars): 4,800 hectares of misty, mostly primary Andean cloud-forest on the western fringe of the Intag Valley in northwestern Ecuador. It’s among Earth’s most biodiverse ecosystems. More than 727 fungi species, 400 birds, six cats, and three primates—including the famously loud Ecuadorian mantled howler monkey—live here. Some 200 species are at high extinction risk. Much of the science behind these statistics has unfolded in the Los Cedros Scientific Station—the forest’s only human structures, including this hut.

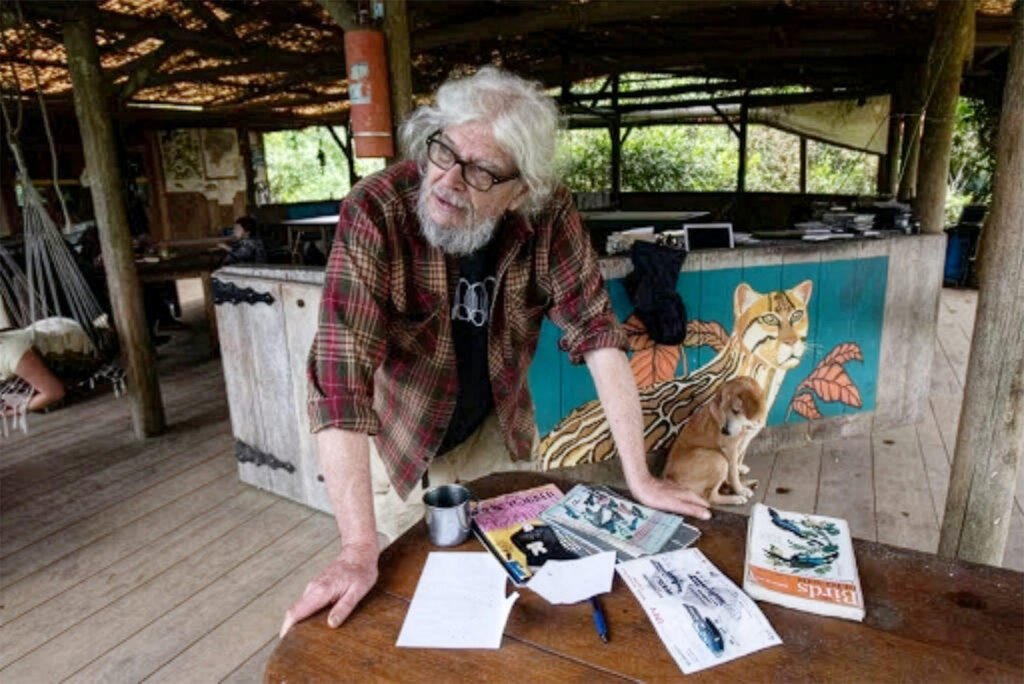

Among those gathered is a shaggy giant named Josef DeCoux, the station’s lone human resident, cohabiting with his two dogs and six cats. American by birth, DeCoux bounced about Latin America before landing in Quito in opaque circumstances in the 1980s. Shortly afterward he pitched a tent in Los Cedros and commenced a cantankerous vigil as its denizen protector. Alongside local communities and international NGOs, DeCoux purchased this land in 1988, established the station in 1989, and spearheaded the land’s 1994 designation as the Los Cedros Cloud Forest Reserve.

DeCoux also initiated the “case of the century” that made Los Cedros famous. In 2021, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court ruled that mining violated Los Cedros’s “rights of nature,” a term describing legal rights held by nonhuman natural entities and broader legal efforts to recognize nature as an active legal subject with agency and intrinsic value. Two judges on the case—reserved Agustín Grijalva Jiménez and exuberant Ramiro Ávila Santamaría—are present, beholding for the first time the forest they have helped protect.

They are accompanied by international activists: writer Robert MacFarlane, who is researching a book, Is a River Alive? (from which the details of this night are drawn); César Rodríguez-Garavito, a legal scholar evaluating the 2021 ruling’s impact; mycologist Giuliana Furci, hunting fungi species; and Cosmo Sheldrake, a musician recording the forest’s soundscape.

This improbable convention—committed to defending Los Cedros with laws, stories, science, songs, and vigilance—has gathered to learn, build solidarity, and strategize. Because while last year’s case was a major victory, the forces menacing the Intag Valley persist. Vásquez reports horrific news from the north: anti-mining activist Alba Bermeo Puin, five months pregnant, murdered—allegedly by gunmen working for illegal gold miners who moved in after activists thwarted a legal mining operation. The news hangs heavy in the hut.

Rights of nature is often framed as a legal movement revolutionizing human–nonhuman relations. But Los Cedros’s story, including a critical chapter currently unfolding, shows that the movement is multifaceted, its revolution contested, and its prospects imperiled. Ecuador’s experience helps answer the question: Can nature rights really work?