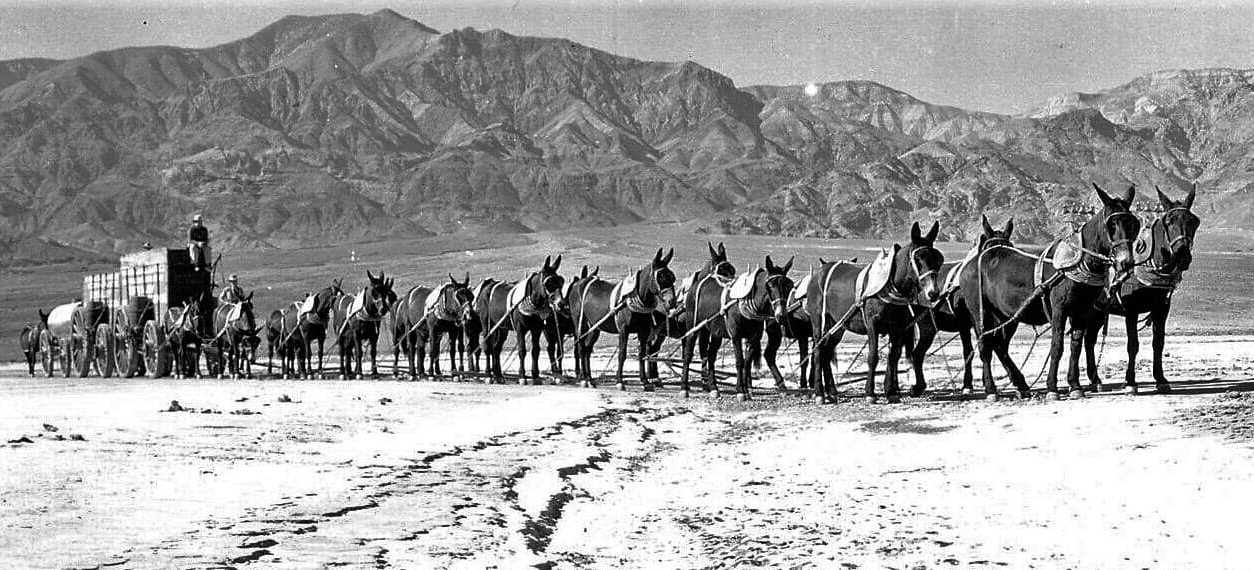

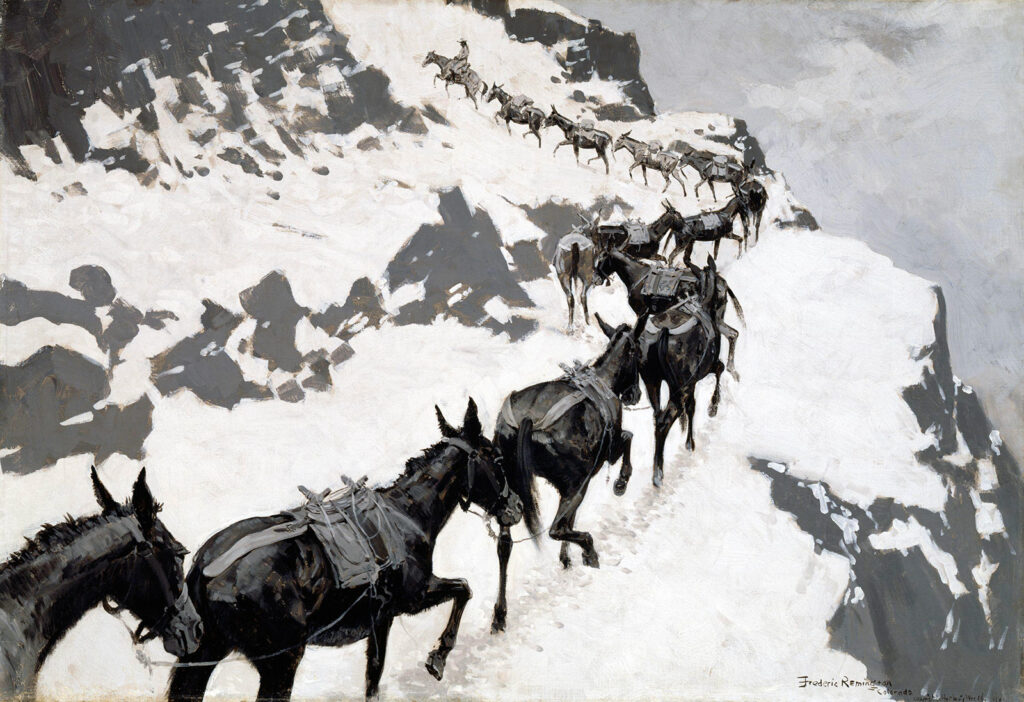

SURE-FOOTEDNESS was key to the everydayness of empire, moving power and products from place to place. Empires, no matter their size and reach, do not traverse land miles at a time but step by treacherous step.

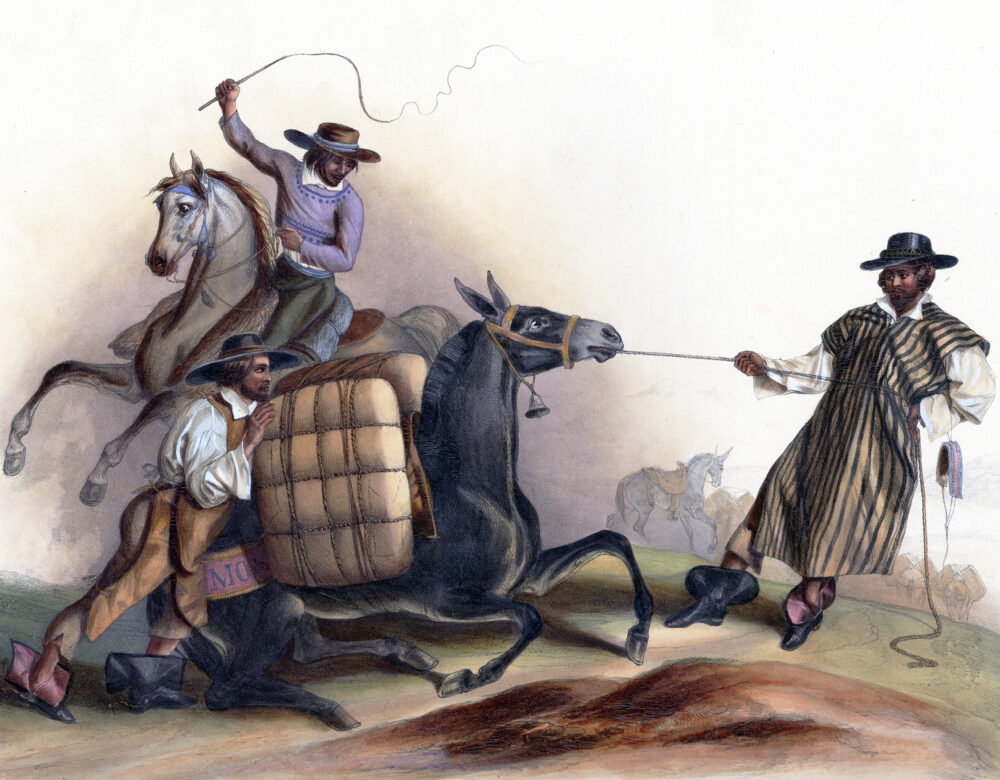

The conquistador on horseback offers an image of how colonialism moved through the Americas, but neither horse nor conquistador had the dexterity to scale mountain ridges or manage plantation rows, at least not as well as mules and their black and Indigenous handlers. Horses come with speed, social status, and occasionally courage. Still, their strides are too long and inconsistent to carry strenuous weight in extreme conditions. For that, empires needed mules.

A mule is a hybrid: the offspring of a male donkey (Equus asinus africanus) and a female horse (Equus caballus). Sex matters here. Due to the smaller womb of a female donkey, its offspring with a male horse produces a genetically identical but smaller equine called a hinny. The 160 or so breeds of mules worldwide today resulted from attendance to this sexual distinction and global trade. From their debated origins in Turkey, Egypt, or Ethiopia thousands of years ago, mules have accompanied many different peoples and cultures. Mules show up early in the Old Testament. Mules appear in Egyptian tombs alongside pharaohs. Mules crossed the Alps with Hannibal and his famed elephants and crossed the Atlantic with conquistadors Christopher Columbus and Hernán Cortés, who turned them into engines of empire, especially in Mexico.

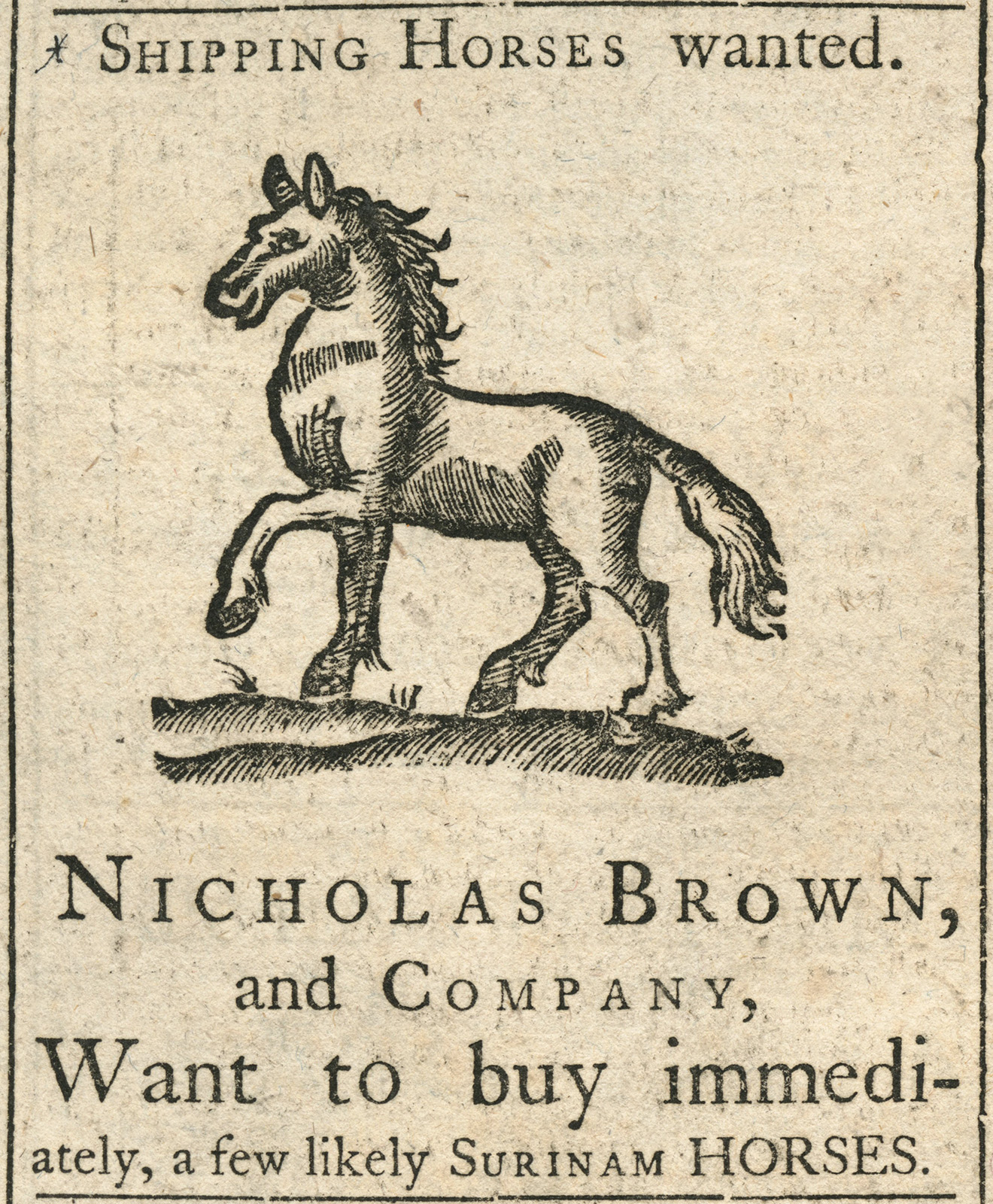

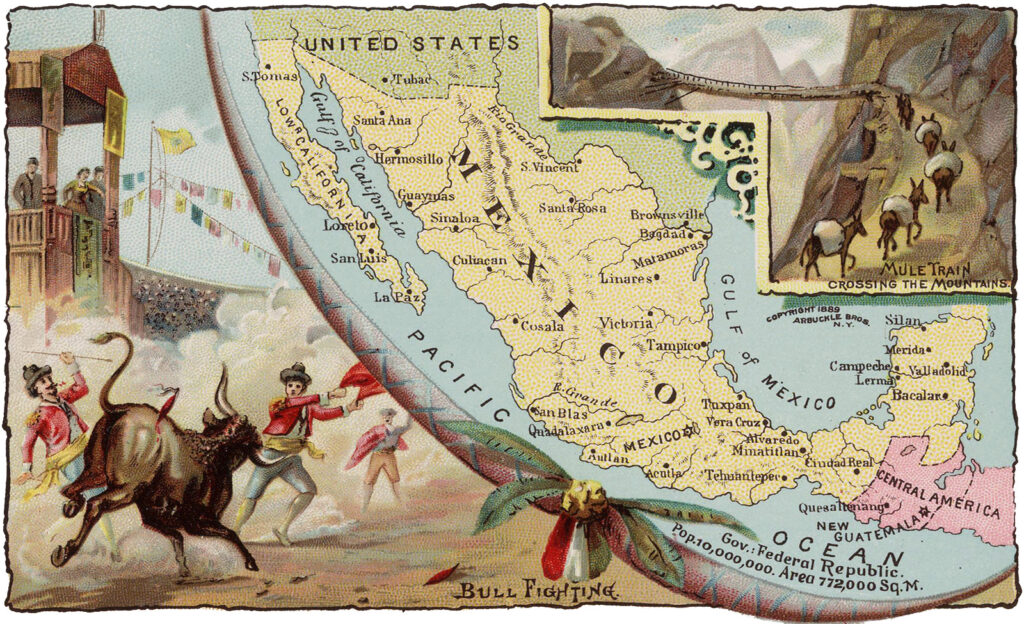

The Spanish and Portuguese empires traveled across the Americas on mules. In Europe, the Iberians dominated mule culture. They domesticated and bred their donkeys and mules in the semi-arid highlands of the Pyrenees, an upbringing that translated well to the high plateaus and mountains of Mexico, South America, and the American West.

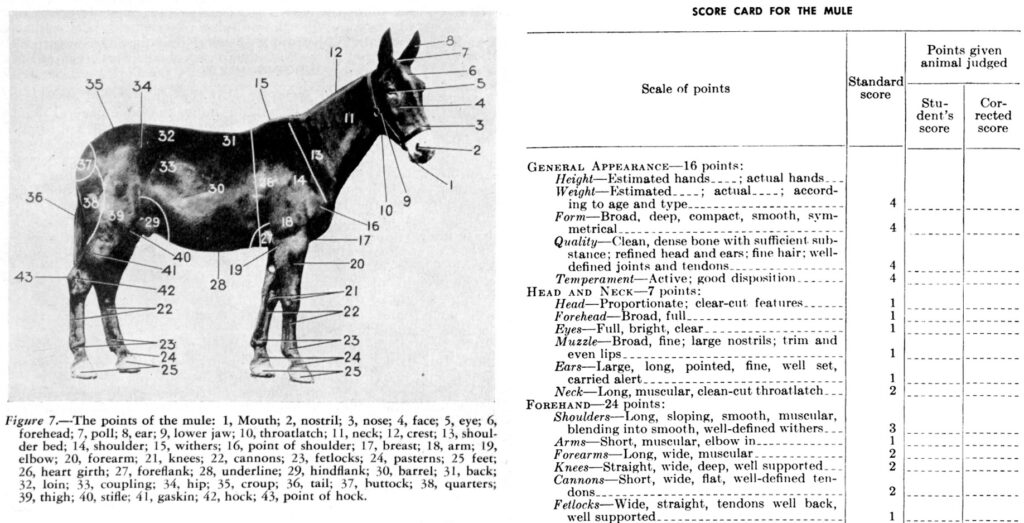

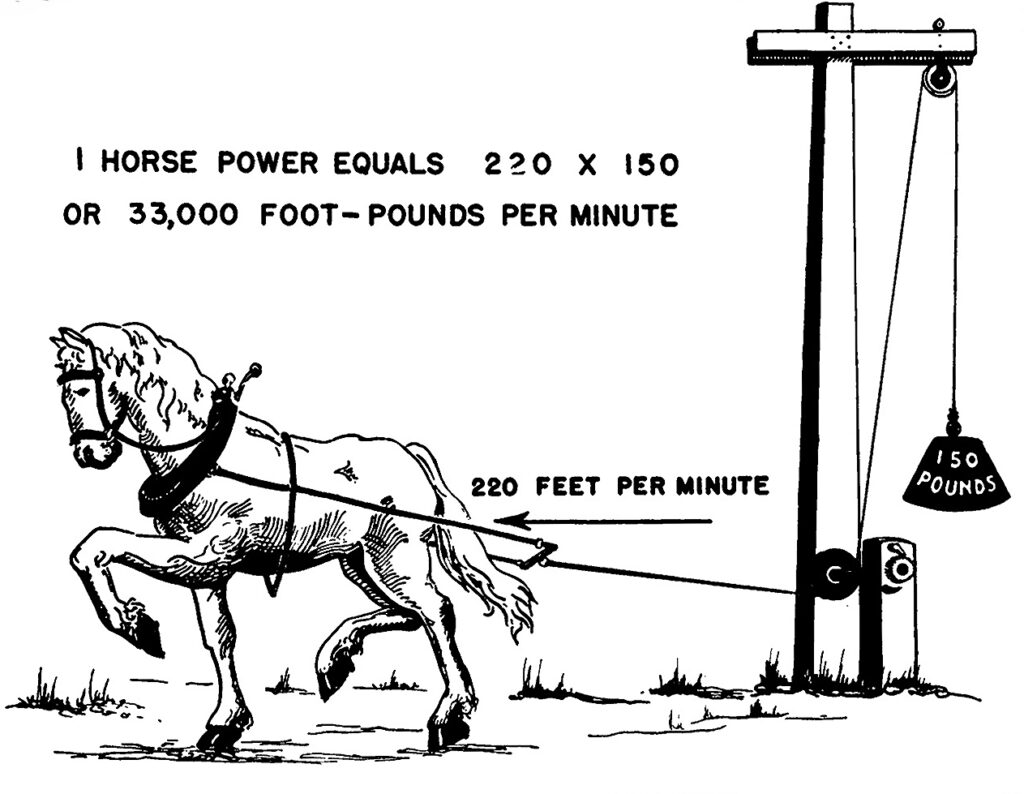

Mules were designed to survive challenging terrain and tasks. Mule vision, foot size, steadiness, and hearing make them better draft animals than horses and oxen. Their regular gait also makes them easier to ride. People who work with them tend to “agree that mules possess the sobriety, patience, endurance, and sure-footedness of the donkey as well as the vigor, strength, and courage of the horse.” Mules have tougher skin and hooves than horses and on average can carry 5% more of their body weight. Their hooves are more equipped to traverse prairie grass than oxen and can better withstand the shock and abrasion of crossing rocky, “boulder-strewn” terrain and the uncertainty of rainy or snowy trails. Horses, on the other hand, require more water, special foods, and additional recovery time.

English speakers usually refer to the caretakers and drivers of mules as muleteers. People know them by many other names in the Americas. Latin Americans call them arrieros in Spanish, arrieiros in Portuguese, and by a number of Indigenous names—oztomeca pixqui in Nahuatl and apiri in Quechua are two examples. Yet mule driver or arriero doesn’t translate well and evenly across Indigenous cultures and regions. Globally and historically, most mules respond to calls from arrieros. As of 2021, over half of the world’s mules lived in Spanish America, with a third calling Mexico home. How this happened has everything to do with the Spanish empire, slavery, and racial capitalism.

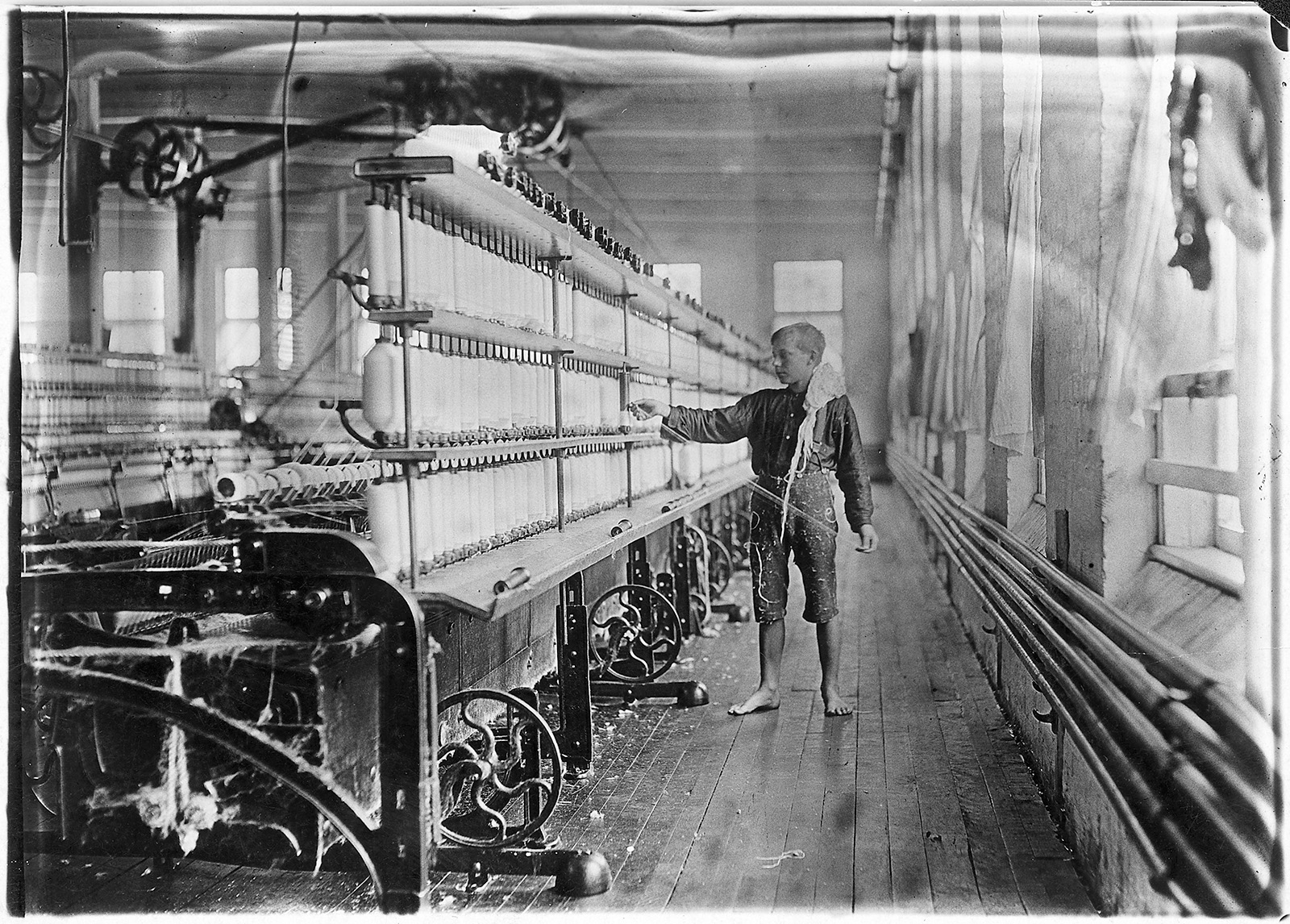

Historian Elinor Melville chronicles a “plague of sheep” that devastated environments in New Spain through their rapid and uncontrolled reproduction. But whereas sheep proved accidental weapons of conquest, mules were calculated tools. Unlike most livestock, mules cannot reproduce. Instead, mule breeding increased alongside Iberian expansion of colonial mines and plantations and the racialized laborers who drove mules for empire (until those laborers used mules to drive empire away).

Jesuit missionaries, large landowners and major investors in the slave trade, took colonial breeding practices to new heights via the largely Indigenous and black arrieros who reared and worked their stocks. Across the 17th and 18th centuries, Jesuits bred mules for plantations and mines from Mexico to Argentina. Colonial extraction drove mule variation as much as landscape. Mines made mine mules and plantations made plantation mules. Jesuits retrofitted their haciendas north of Mexico City to breed mules for sugar plantations in Morelos. In the dry areas of Zacatecas and Durango, they reared mules for silver mines. In Brazil, where the Portuguese established their 18th-century mule culture around gold mining, trains of Jesuit-raised mules called tropas carried gold south to Rio de Janeiro. Even farther south in Río de la Plata, Jesuits bred mules in the semi-arid grasslands of Argentina for shipment to silver mines in Bolivia and Peru.

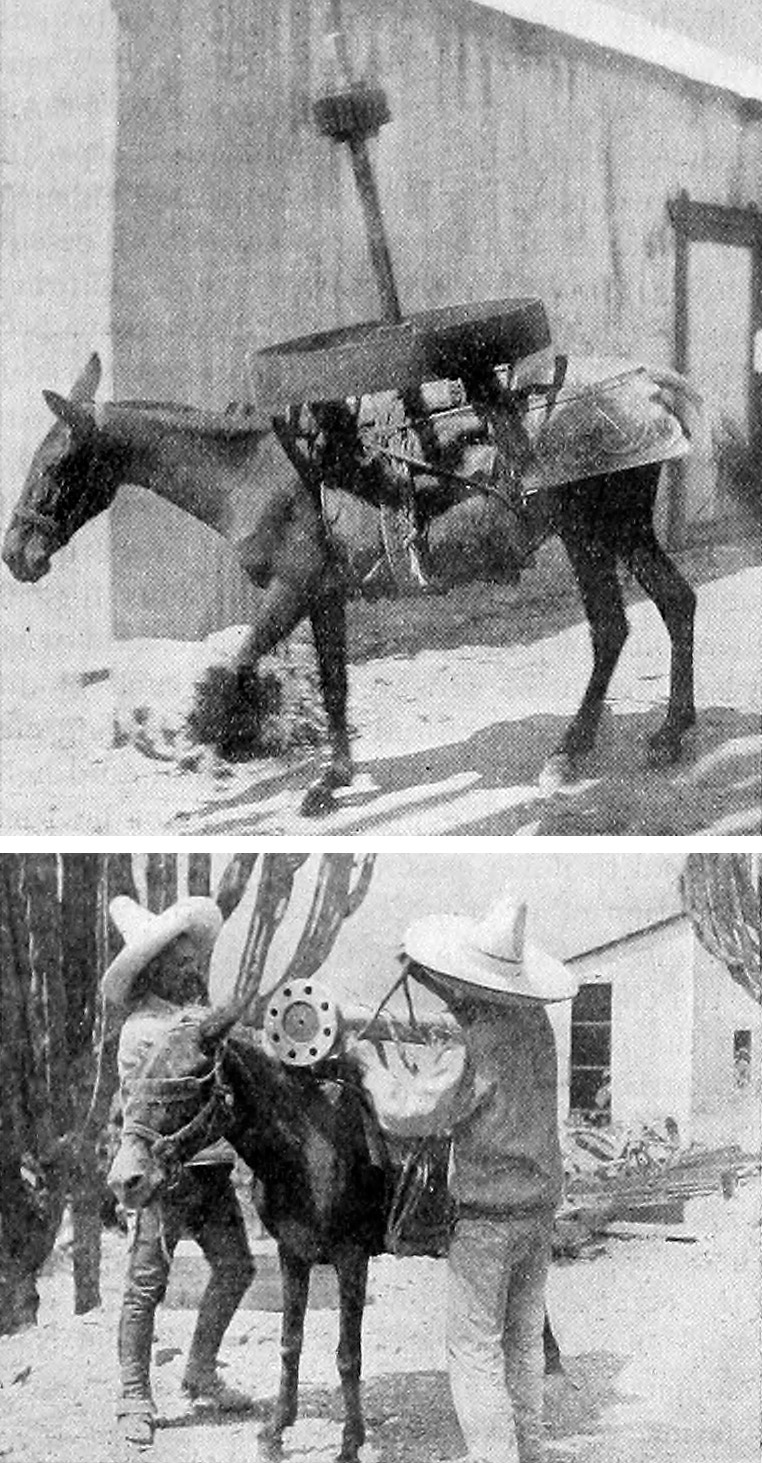

If Jesuit husbandry shaped Latin America’s mules, the region’s diverse environment made arrieros. Sixteenth-century officials in Mexico witnessed a “genuine class of Indian muleteers” to lead these teams of animals. It was not enough to know how to wrangle 20 to 200 animals. Arrieros were products of long apprenticeships with harsh men and harsher land, including an education in local ecosystems and how they transition into microclimates as you travel up mountains and down into valleys. Securely fastening cargo to mules trekking through dense forests and mountain ranges was not an easy feat. To prevent injury and constant readjustment, packing mules properly was a “chief display of skill” requiring “good judgement and long practice.” Arrieros held the skills of veterinarians, blacksmiths, and foragers. They knew the most navigable and nutritious landscapes and how to remedy a snakebite or a gash.

One eyewitness in the 1850s described how arrieros remembered “secret paths among the trees” to return home. Another observer understood muleteering as a “unique occupation” involving a “thorough acquaintance with the mountain region, the camping grounds, pasturage, [and] the state of the roads and streams.” They witnessed how arrieros “depend upon pasturage entirely for feeding their animals en route, except during the height of the dry season.” When the land could not provide for their mules, arrieros relied on communities growing corn and designated mules to carry it rather than other cargo. Arrieros were the glue between plantations and ports and more remote communities. They helped transform sparsely populated landscapes into living and breathing colonial societies. They became “conduits through which news and rumors flowed in rural areas,” which helped with recruiting insurgents to rally against the Spanish. But, like Paul Revere during the American Revolution, arrieros did more than sound an alarm. They served as intelligence and military officials in the resistance to empire.