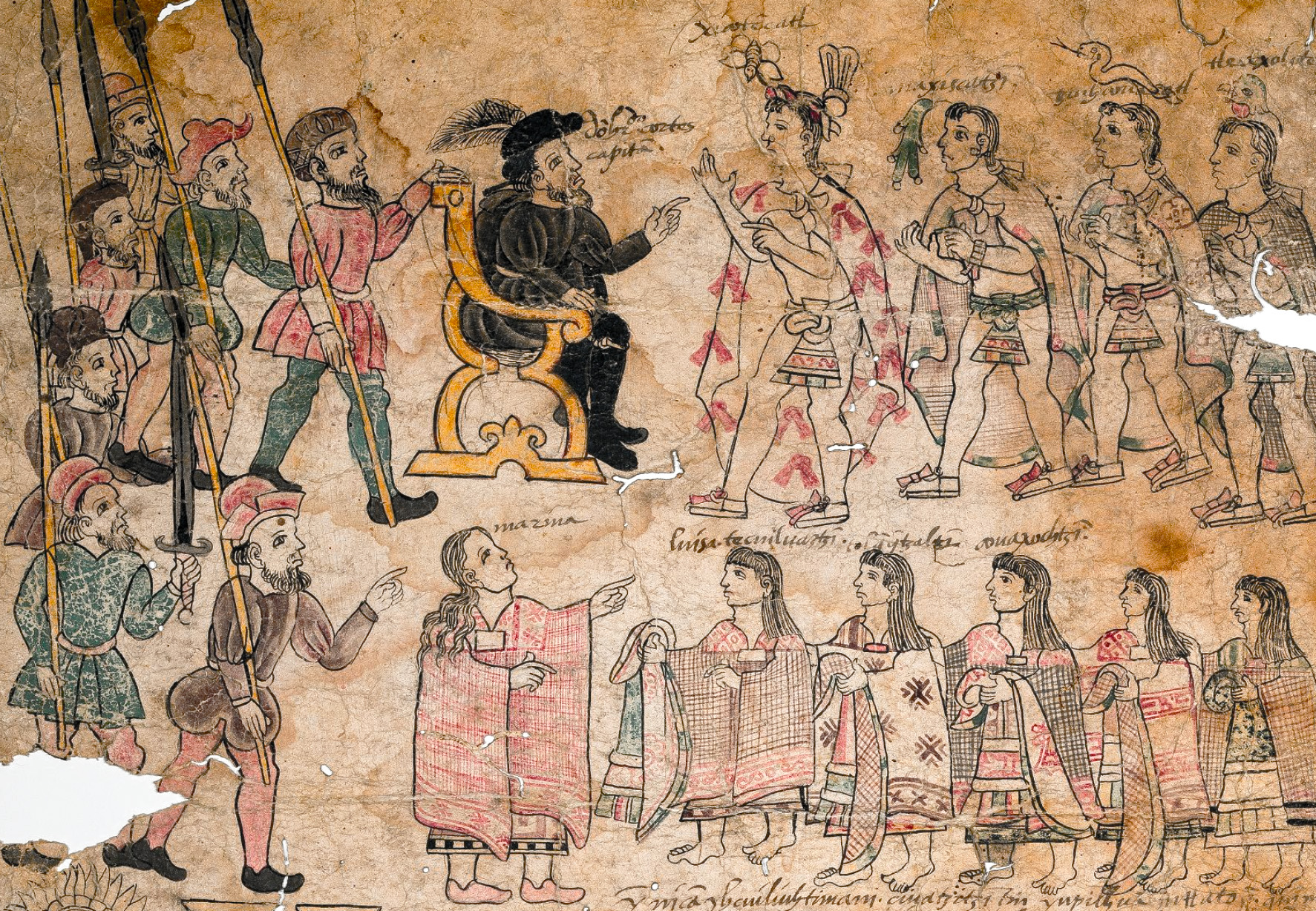

On an April day in 1585, four Indigenous noblemen from the central Mexican province of Tlaxcala presented a list of urgent concerns to King Phillip II of Spain.

Spanish colonists kept encroaching on their territory, the men complained, allowing livestock to roam free and destroy cropland. Every decade, it seemed, another disease or famine swept through the highlands of central Mexico, leaving death and disability in its wake. The province’s population continued to plummet, but tribute payments demanded by the Crown stayed stubbornly constant, which had compelled these emissaries, like others before, to beg for mercy.

It had been nearly a year since the nobles—Antonio de Guevara, Pedro de Torres, Diego Tellez, and Zacarías de Santiago—began their trek across the Atlantic for an audience with the king. So, with such pressing topics in mind and no moment to waste, why would they spend time, as they did that day, defending the reputation of a local insect?

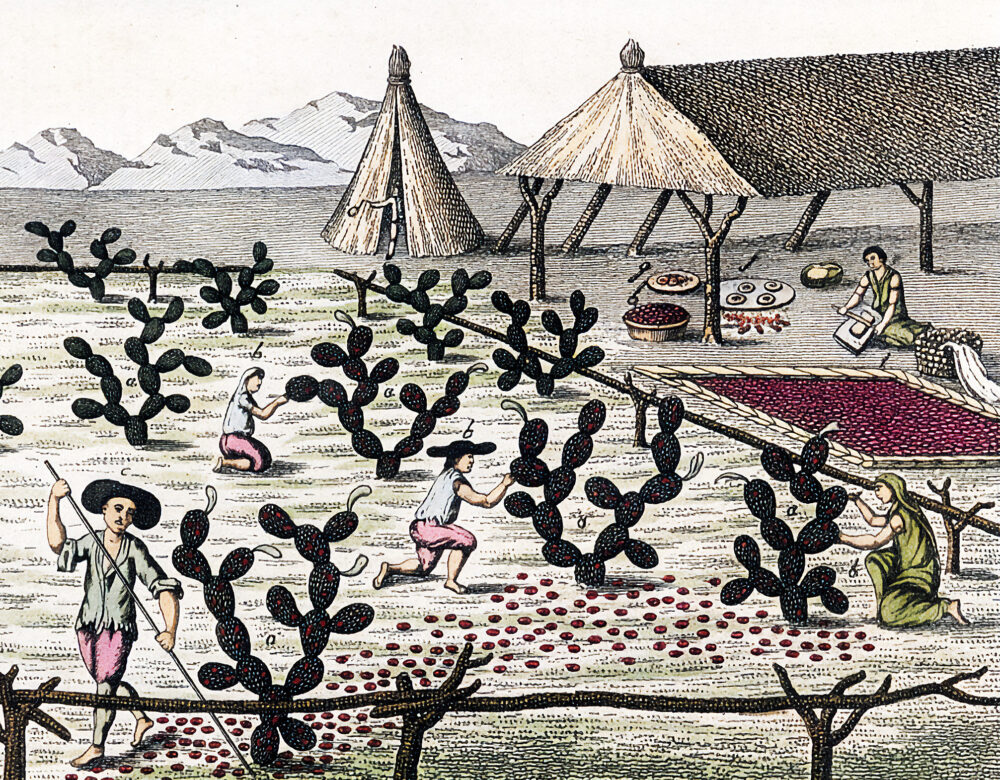

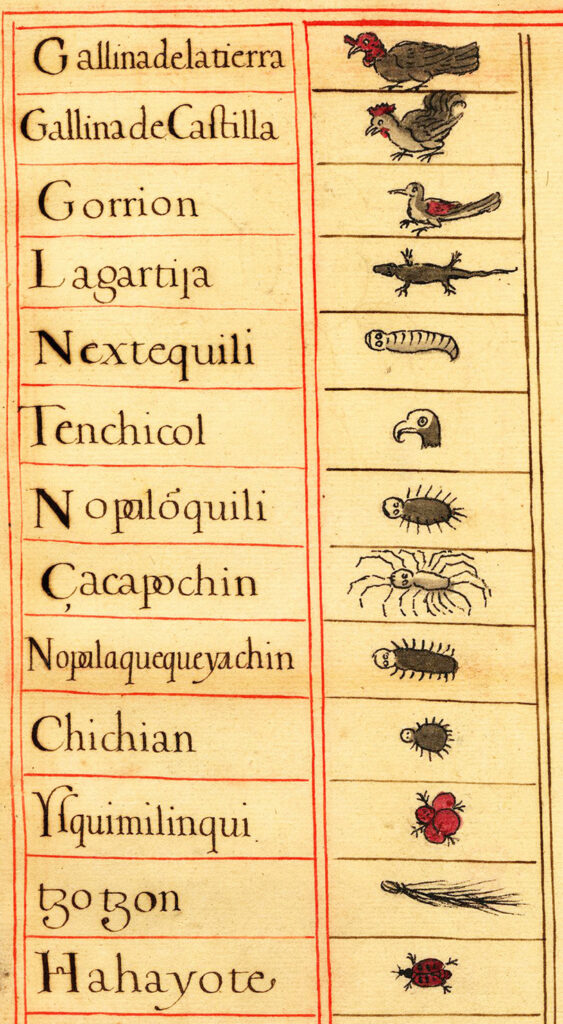

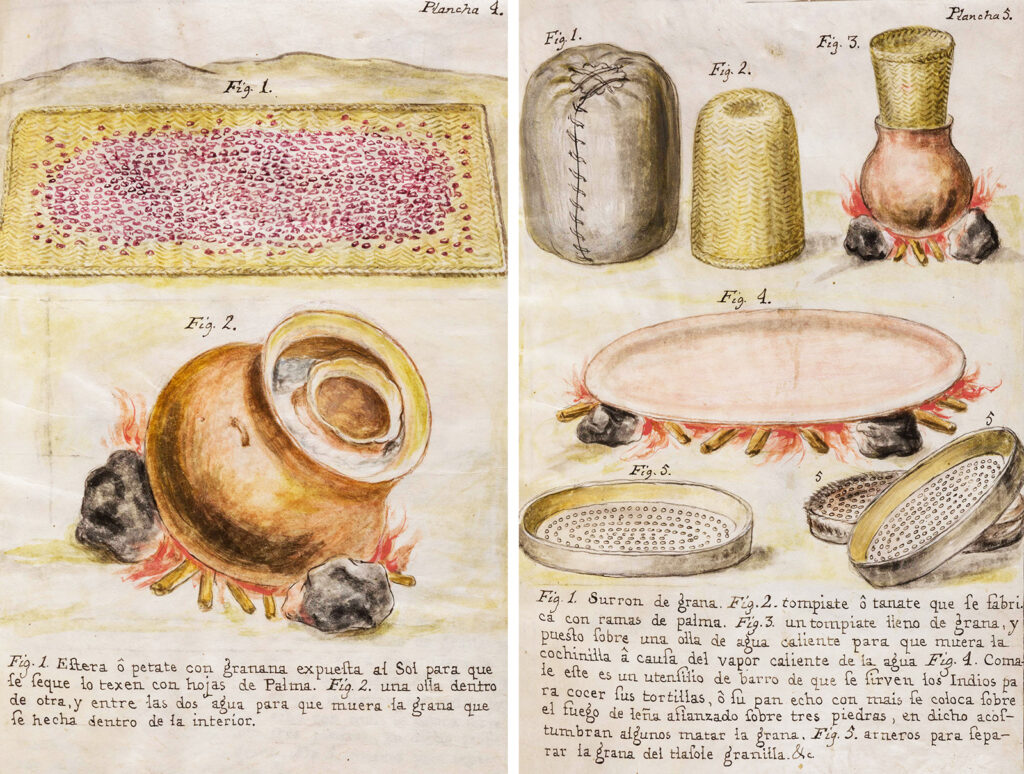

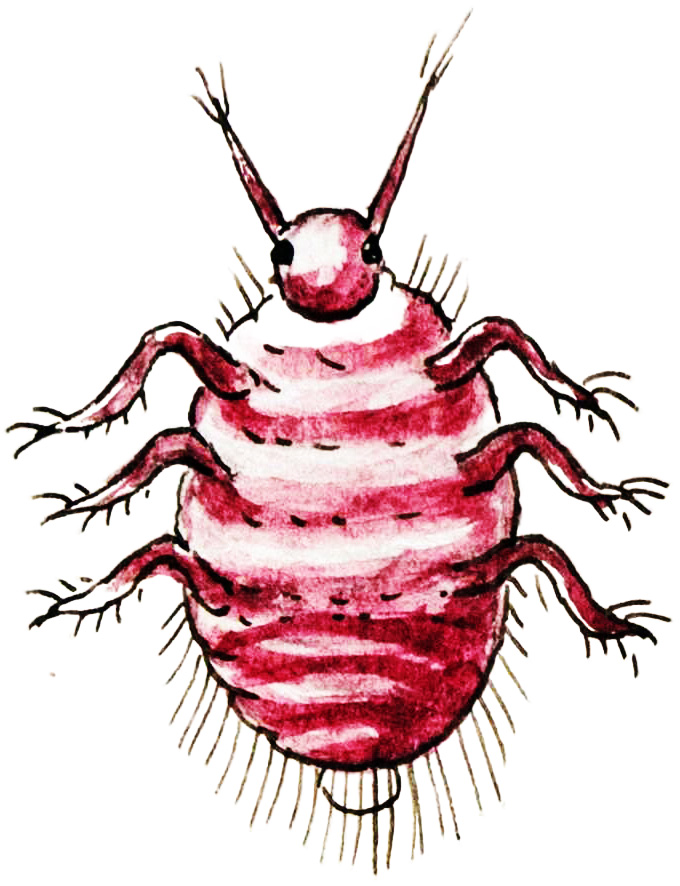

As it happens, that insect was cochineal—at the time the most important cash crop in New Spain. Though cochineal is a tiny, unassuming white bug that spends its entire three-to-four-month life on prickly pear cacti, the inside of its body is an intense red. Dye made from cochineal was one of early modern Europe’s most sought-after substances, used to make vibrant clothes, paints, makeup, and even medicine. Although other insect-based red dyes existed, cochineal dye was far more concentrated, which allowed artisans to achieve deeper reds while using less raw material.

The Spanish Crown enjoyed a monopoly on the colorant through its holdings in Mexico and Peru, where cochineal was traditionally grown and produced. Depending on the year, cochineal could be worth half its weight or more in silver, the only export to consistently outpace cochineal in the wealth it delivered to the Crown over three centuries of colonial rule. It was so valuable and so frequently stolen by rival European powers that in 1674 Spain required all shipments of cochineal be transported on, or with the protection of, its warships.

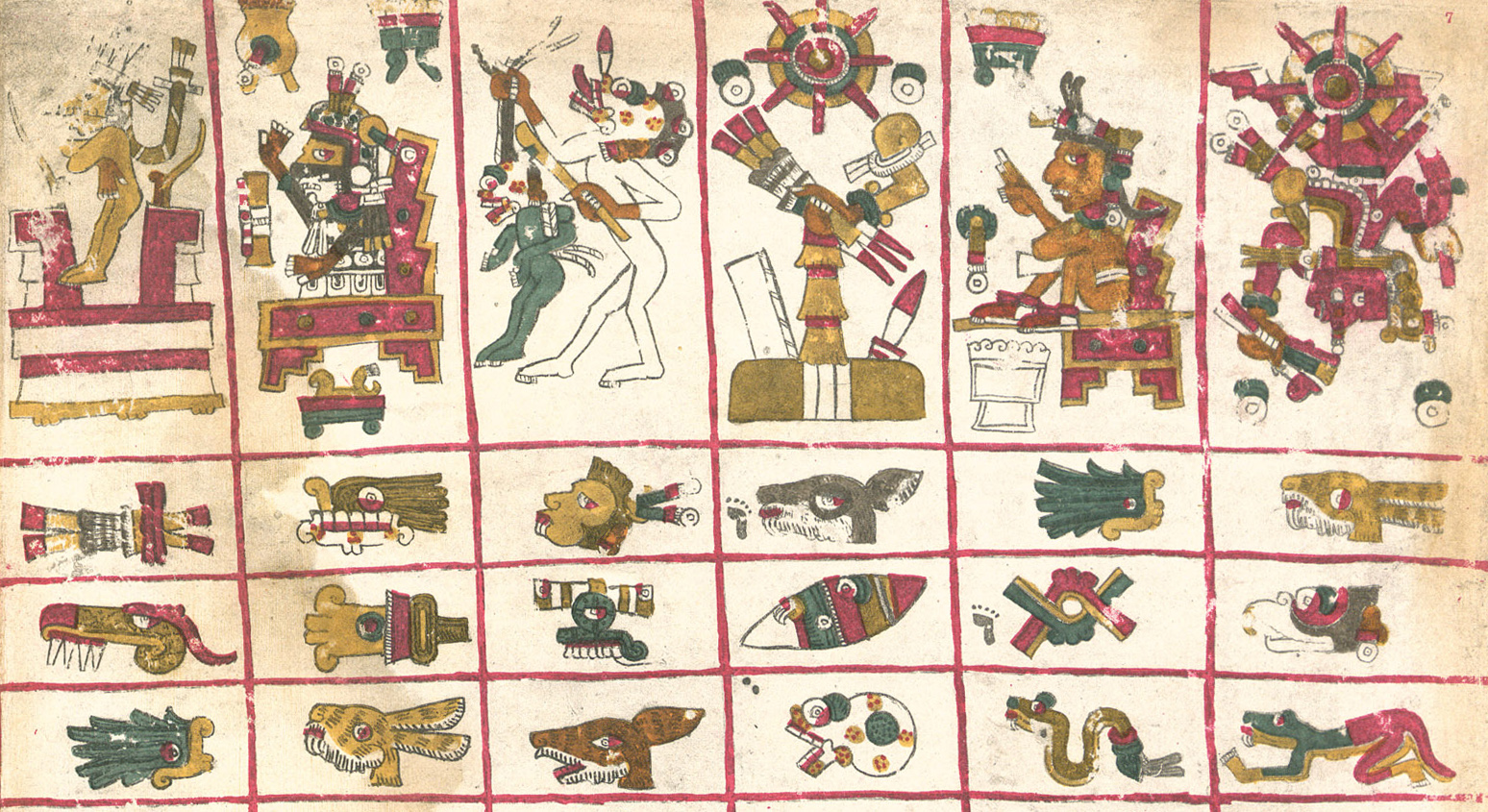

The oldest Mexican textile known to contain cochineal is approximately 2,300 years old, but scholars aren’t sure how long the dye has been produced in Tlaxcala. Only a few pre-Hispanic books from Tlaxcala survived Spanish friars’ fanatical hands, and none describe cochineal production. Evidence of cochineal usage, though, is embedded in the pages themselves. Chemical analysis of their still-vibrant pictographs shows that by the 1400s Tlaxcalteca were using cochineal-based paints to document calendrical and astronomical events.

But where people used cochineal doesn’t necessarily tell us where they produced it. In the 1400s, trade networks were extensive; archaeologists have shown that people in central Mexico had access to turquoise from as far north as New Mexico and ceramics from as far south as Costa Rica.