One afternoon in 1941, three teenage girls gathered outside the red brick building of the Trafalgar School for Girls in downtown Montréal. Most days, school was dismissed early with the expectation students would spend the afternoon studying at home. Once a week, though, classes continued into the afternoon. On these days my grandmother Jane Hildebrand and her friend Marilyn Richardson would lunch together at an eatery on St. Catherine Street. That was until they befriended another student, Monique Zimmerman, who introduced them to the Salad Bar.

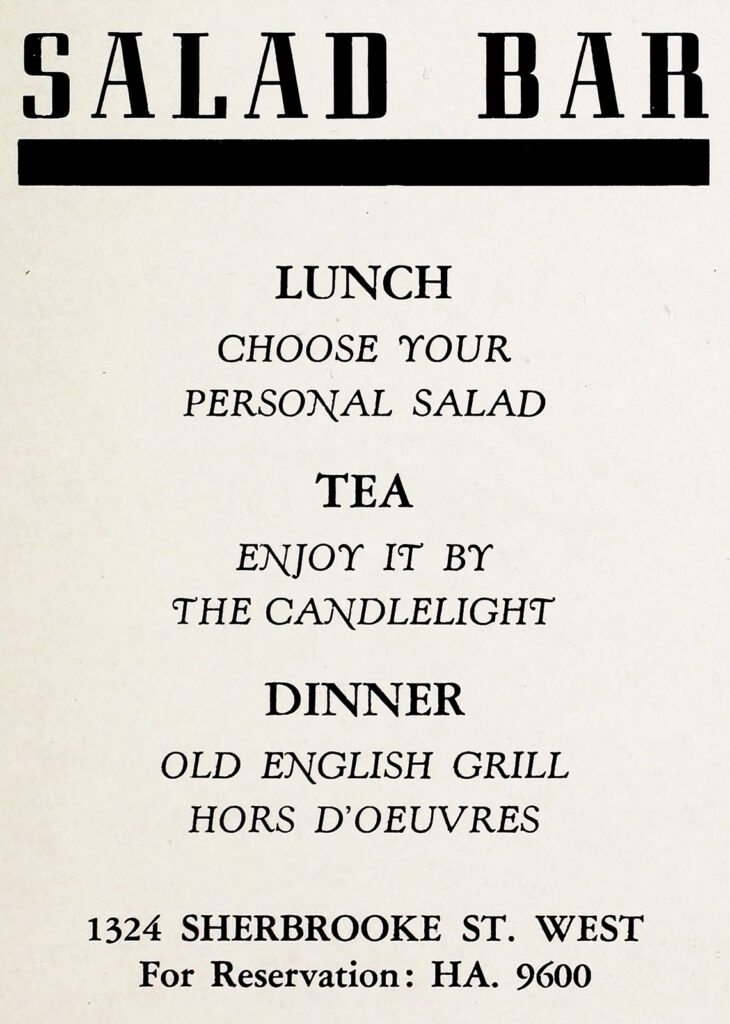

One of the first vegetarian restaurants in Canada, the Salad Bar opened in the late 1930s, catering to a health-conscious, working clientele. It was a success, unimpeded by wartime rations on meat or the conscription of its owner and chef, Monique’s mother.

“When Monique took us down to the restaurant for the first time, it was wonderful for Monique, it was wonderful for us, and it was wonderful for Madame,” Jane later recollected. Little did she know she was brushing shoulders with celebrity. Monique’s mother would, in time, become the “grande dame of Canadian cooking,” known across the country as Madame Benoît, Canada’s French Chef.

It is tempting to equate Madame Benoît with her American counterpart, Julia Child. Both women studied cooking in Paris, ran their own cooking schools, and wrote popular cookbooks. Both traveled overseas during World War II and returned to homelands yearning for peaceful domesticity and “normal” family life. After stepping up to relieve the wartime labor shortage, women were expected to make way for returning soldiers. Benoît and Child led the charge back to the kitchen—and made careers doing it. That wasn’t the only irony. Espousing the virtues of home cooking from faux kitchens, these pioneering celebrity chefs appealed to the culture’s anti-modernist yearning for the “good old days” via the new mass communication technology of television.

Despite their similarities, Child and Benoît were different in significant ways. For one, they held fundamentally different philosophies of food.

Child, a gourmand, played to the cosmopolitan ambitions of midcentury American housewives. The TV show The French Chef presented her as a paragon of continental culinary sophistication who was refining the United States’ banal food culture. Benoît catered to a different crowd. She was French Canadian and a chef—but she was not a French chef. Benoît was a pragmatist and a positivist who prized scientific inquiry, efficiency, and nutrition.

While Child cooked French food, Benoît constructed a Canadian food patrimony out of its traditional regional dishes and multicultural influences. Child revered traditional techniques; Benoit was moved by a faith in novel, labor-saving technologies that flooded postwar Canada. And no technology captivated her attention more than the microwave.

The microwave was a time machine. With Madame Benoît at its controls, it cut dinner prep to a fraction of the time and transported the food of Canada’s past into the future.

An Education in Food Science

Born Jehane-Cécile Patenaude in 1904, Benoît was raised in Montréal’s prosperous Westmount neighborhood. Descended from rural bakers and cattle ranchers, the Patenaude family remained oriented around food and the land even after it joined the urban elite. Food was not merely eaten; it consumed dinner conversation. In the depths of the Canadian winter, Benoît’s grandfather would drive a sleigh 20 miles to reach his preferred bakery. Summer at her grandparents’ house was welcomed with homemade croissants spread with strawberry jam.

As a teen, Benoît was sent to board with Les Dames du Sacré-Coeur, a Montréal convent school run by Parisian nuns. She continued her education in 1920 under the same order in Paris, chaperoned by her mother. Benoît returned to Montréal briefly after finishing university. Despite her mother’s entreaties to marry and settle down, she dreamed of returning to Paris to become an actress.

“She could not tell her parents ‘I want to go to France to be on the stage,’ ” her second husband, Bernard Benoît, later wrote. Instead, “she addressed the gourmet nature of her father” and asked to go to the Sorbonne to study cooking.

In the 1920s, food science was a booming field, propelled by research during World War I to supply soldiers with nutritious, shelf-stable foods. The field’s ascent coincided with the rise of first-wave feminism and its insistence that women had a right to education. Departments of domestic sciences sprung up during this time, siphoning young women from respectable middle-class families into silos of gender-appropriate study. That’s the retrospective view, at least. At the moment of their invention, they were a way to legitimize women’s labor by making it scientific. The domestic sciences were a “foot in the door” of the university system for women.

Against this backdrop, Benoît moved back to Paris, planning to attend classes at the Sorbonne by day and acting school at night. As it happened, however, the Sorbonne had recently appointed Édouard de Pomiane chair of its Department of Culinary Physics and Chemistry.

Pomiane was a biologist and leading researcher at the Pasteur Institute who specialized in understanding the chemical changes food underwent during the cooking process. In 1922 he published Bien manger pour bien vivre (Eat Well to Live Well), in which he argued that good food was the gateway to health. In his follow-up, Cooking in Ten Minutes, or Adapting to the Rhythm of Modern Life, he dispensed with the pretensions of haute cuisine, favoring instead wholesome meals made quickly with modern cooking technologies. This work rapidly gained currency in the 1920s as the electrification of urban homes spurred the adoption of refrigerators, mixers, ovens, and other electric appliances.

“I went to Paris to start my course in food chemistry and just fell—how do you say that—line, hook, and sinker for my teacher [Pomiane]. He was a fantastic teacher. And I got keenly interested,” Benoît told the CBC in 1971. “So, maybe I wasn’t to be an actress at all.”

Three years later, in 1925, she graduated from the Sorbonne with a degree in food chemistry. She stayed another year in Paris to study at Le Cordon Bleu under Henri-Paul Pellaprat, another leading figure of l’art culinaire modern.

With her training complete, Benoît contemplated her next step. “What I want to do is go back to Canada and revolutionize the whole food of my country,” she later remembered thinking. “Of course I didn’t do quite that, but I tried to do a little bit.”

Jehane’s Salad Days

Upon her return to Montréal, Benoît married a local businessman, Carl Otto Zimmerman. Their daughter, Monique, was born in April 1927. A few years later, during the depths of the Great Depression, Benoît opened a bilingual, pay-what-you-can cooking school for Montréal housewives, Au Fumet de la Vieille France. Good food, Benoît reiterated throughout her career, required a chef who cared about those eating it. “Of course, a woman in love cooks much, much better,” she later told Maclean’s magazine. But while her school thrived, behind the scenes Benoît’s marriage quietly came apart.

Around this time Benoît opened the Salad Bar at 1324 Sherbrooke Street West, a mansard-roofed townhouse beside luxury retailer Holt Renfrew in Montréal’s exclusive Square Mile district. “How she knew there was a market there, I don’t know, but she was right—there was a market for people who wanted healthy food,” Jane said. “I just remember that her salads were extraordinaire.”

Melding her training in nutritional sciences with the productivity of early-20th-century manufacturing, she optimized the salad-making process. A long assembly line of prepared vegetables and toppings allowed customers to customize salads to their liking. Benoît managed the old property with similar efficiency. The Salad Bar operated out of the main floor. In the basement beside the boiler, Benoît sublet a small room to an English war evacuee, who set up a dress shop. Above the restaurant were several more rooms in which Benoît ran the cooking school and lived with Monique. Among these rooms was a business office, soon occupied by Bernard Benoît, whom she hired to do administration. Thirteen years her junior, Bernard first became a good friend, then a romantic partner.

It was during the Salad Bar days of the early 1940s that Benoît made her media debut. She was interviewed on Radio-Canada’s Femina, a progressive, French-language program covering women’s issues. Benoît shared wartime ration recipes and asked women to write in with their family’s favorite dishes.

Then, in December 1942, disaster struck. While Bernard was away completing military training, a fire broke out in the boiler room, engulfing the dress shop, restaurant, and rooms above. When it was put out, the soaked interior of the building froze over. Benoît rescued what furniture she could but didn’t have the heart to reopen the restaurant. She transferred the building’s lease to the dress shop owner, who also bought the Salad Bar and continued to run it with several of the restaurant staff.

Jehane moved with Monique into an apartment on Chemin de la Côte-des-Neiges, across the street, it so happened, from Monique’s friend Marilyn. Soon after, Bernard was deployed overseas. Heartbroken from these twists of fortune, Benoît tried her hand at writing a cookbook, but to no avail. A paper shortage prevented its publication, and the handwritten manuscript—on practical and economical cooking during periods of food scarcity—was ultimately lost by the publisher. She made ends meet by giving cooking lessons, appearing in radio programs, writing recipes for food companies, and working as a food consultant for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency.

Then, two long years after Bernard was deployed, Germany surrendered. Benoît did not wait. Accompanied by two French friends eager to return home, she took a steamship to London to meet Bernard. The couple was reunited on August 21 and married a week later. They spent their honeymoon with Bernard’s unit in Holland. Upon arrival, Madame Benoît took over the unit’s kitchen and served the troops a beef casserole.

Rise of a Celebrity Chef

When Benoît returned from Europe in 1946, she found herself starting over again in a country doing the same. What would be her contribution to a rebuilding nation?

Her forays into radio during the war had opened her eyes to the breadth and variety of Canadian food. She was convinced Canada had a distinct food culture, which she began to champion in magazine articles and radio segments, and soon, as a member of the Québécois commerce committee for tourism.

Thereafter, Benoît ascended steadily into the role of celebrity chef and Canadian cultural icon. As television infiltrated the nation’s living rooms, Benoît was there, edifying the masses with nutritional science and Canadian recipes. In the mid-1950s she began appearing on CBC’s TV program Living with Elaine Grand and became a regular guest on the talk show Open House. Though a cutting-edge technology was the vehicle, her work was driven by an old-fashioned noblesse oblige to better Canadian society. Her segments were part cooking demonstration, part lecture on food history and culture. Through the screen, Benoît delivered the same mixture of gracious hospitality and maternal instruction that had endeared her to the Trafalgar schoolgirls during their lunch breaks. “[I] saw her on TV and was delighted to see her again,” remembered Jane, who by that time had become a high school English teacher.

In 1954 Benoît earned a regular spot on Femina, providing cooking advice three times a week. By the end of the following decade, she had published four cookbooks and innumerable columns in Canadian newspapers and magazines.

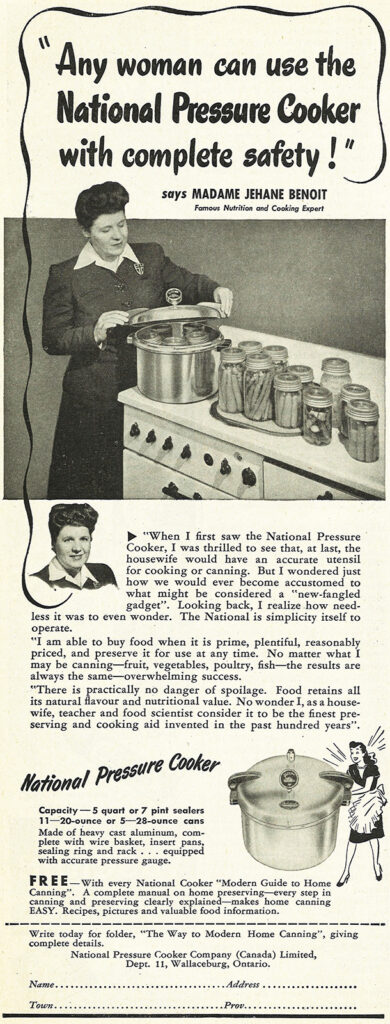

In her appearances and writing, Benoît promoted food preparation shortcuts to ease the workload of Canadian housewives. Often she found the solution in technologies, many of which were discovered through wartime R&D. Sometimes this research led back to old cooking technologies such as canning, first developed by Parisian confectioner Nicolas Appert to stabilize the food supply for Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops.

During World War II women turned to pressure cookers and canners to stretch the shelf life of fruits and vegetables. The demand for these devices spurred innovation—modern versions that were safer and easier to use at home and that proved popular well after the war.

In 1947 Benoît became the face of the National Pressure Cooker company. Canning was an economical activity that demanded technical skill and an understanding of foods’ acidity to achieve proper preservation. In one ad, Benoît describes herself as “a housewife, teacher, and food scientist” (that order intentional) who could vouch for the safety and efficacy of the machine, which “retains all [food’s] natural flavour and nutritional value.”

While Benoît revived old innovations, other, totally new domestic technologies emerged from wartime research.

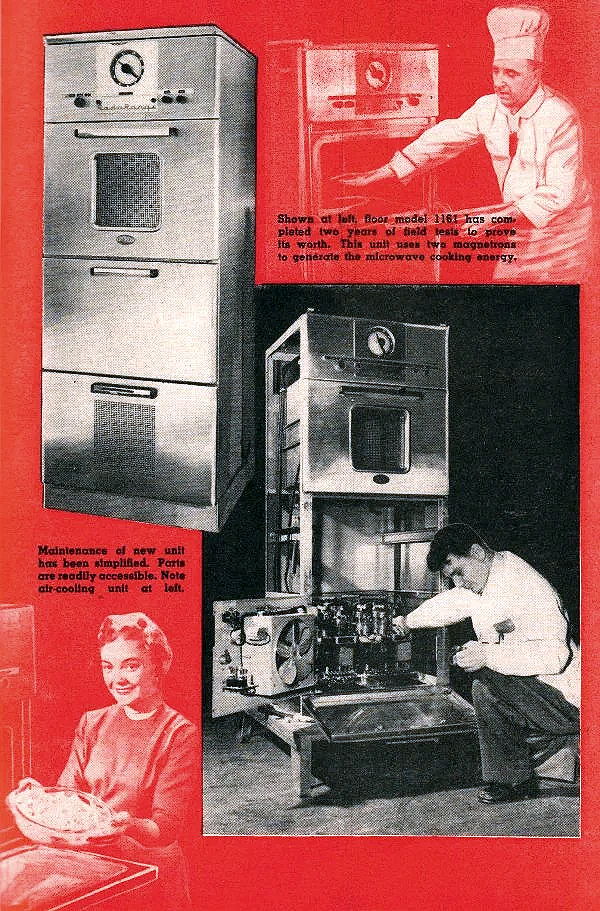

In 1945 electrical engineer Percy Spencer was refining a device called a magnetron at American electronics company Raytheon. The magnetron was a powerful vacuum tube that used a magnetic field to make electrons vibrate, generating short-wave electromagnetic radiation. These short, or “micro,” waves were the key to the Allies’ superior radar technology. As the story goes, one day Spencer was working on a magnetron when he noticed the candy bar in his pocket had melted. A follow-up experiment with popcorn confirmed microwaves’ potential in the kitchen.

Soon, Raytheon had developed the “Radarange,” the first microwave oven. But the device was the size of a fridge, with a price tag in the thousands. It would take two more decades for microwave technology to become commercially viable for domestic use.

Constructing a Canadian Cuisine

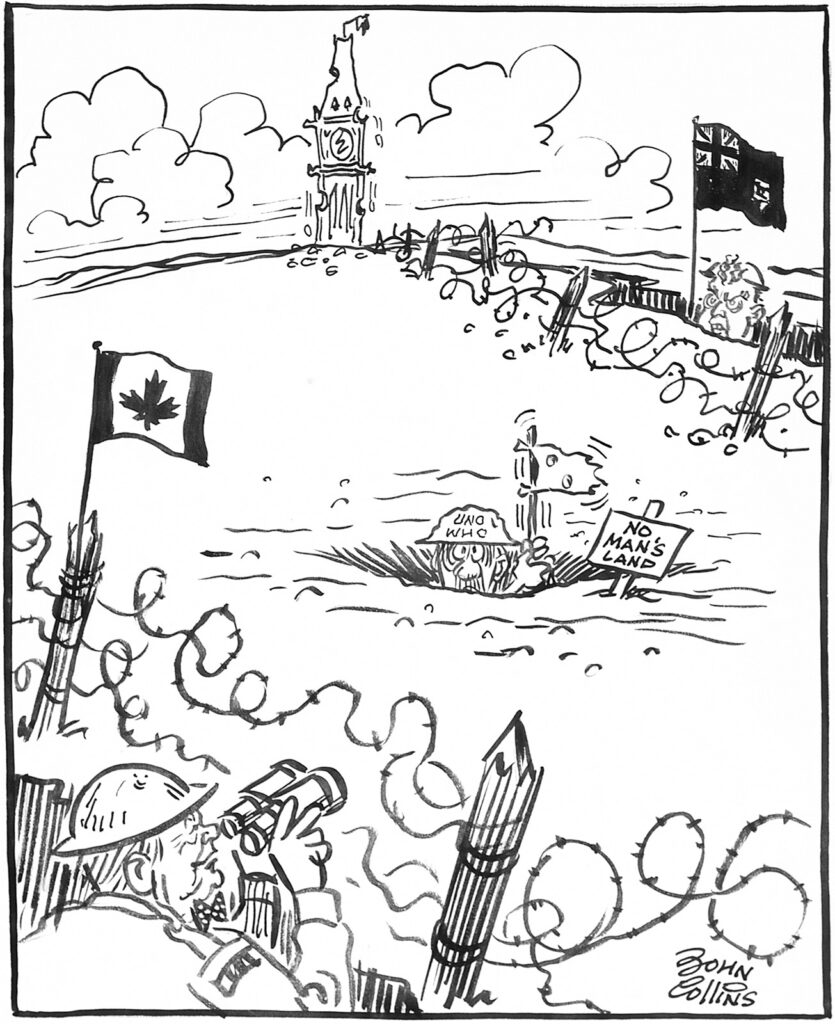

The 1960s were an era of peak Canadian nationalism leading up to the country’s centennial in 1967. Canada sought to step out of Britain’s shadow while differentiating itself from the United States.

While most Canadians could agree on who they were not, it was harder to define who they were. Canada needed cultural and national identifiers all its own. This was a challenge for a young nation with a vast territory that encompassed varied regions and people with different religions, ethnicities, and languages. As illustrated by the political squabbles that marred the Great Flag Debate, reaching consensus was difficult. And the Union Jack’s replacement with the now-familiar Maple Leaf was just the first step. The country also demanded its own canon of art, music, literature—and food.

Benoît, a food chemist and Québécois housewife, had a penchant for reconciling contradiction. The paradox she embodied—innovation and tradition, science and romanticism—was evident in her construction of a national cuisine. In 1963 Benoit published the Encyclopedia of Canadian Cuisine. Her conception of Canadian food reflected the romantic nationalist belief that people’s shared history living in a homeland produced a distinct and unifying identity. “Canadian food,” declared the jacket blurb of the 1974 edition, “is as unique as any in the world.” Yet Canada’s sprawling geography and diverse immigrant groups made assembling a unified national menu difficult. Benoît’s Encyclopedia solved this contradiction by defining the uniqueness of Canadian food by its combination of varied influences.

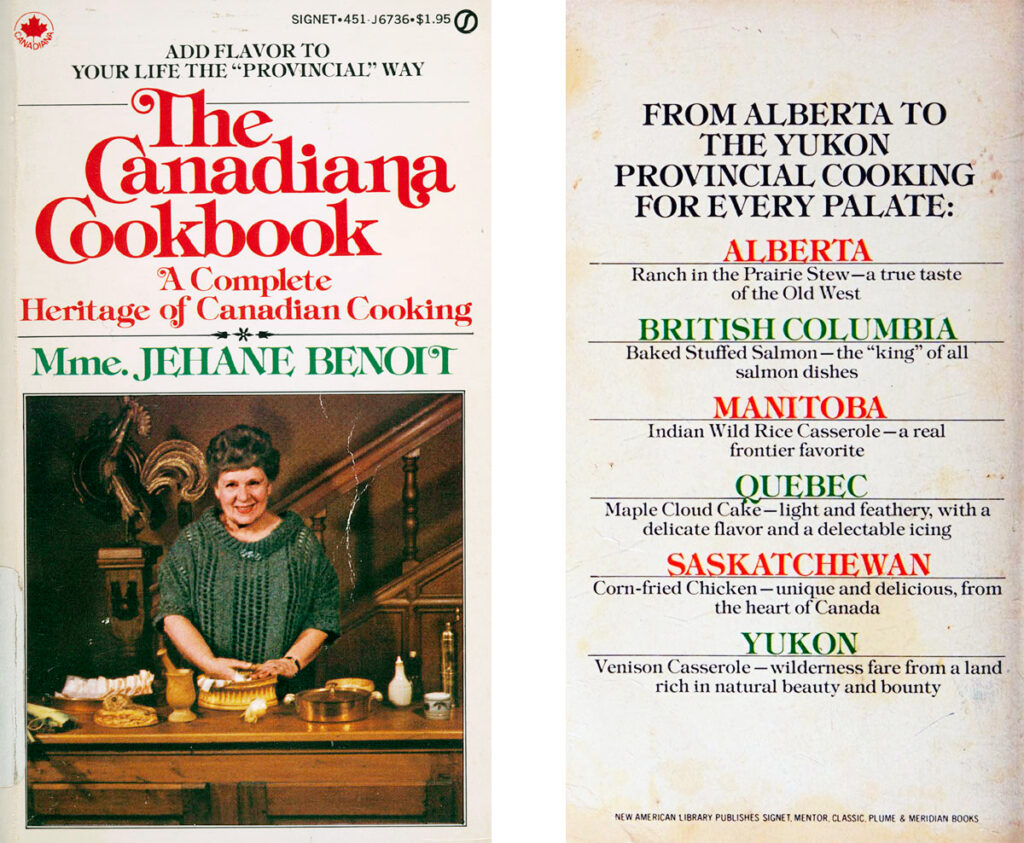

This was a point considered by Pierre and Janet Berton in The Centennial Food Guide, published in 1966. The Bertons proposed that Canada had regional, rather than national, dishes and that Canadian cuisine encompassed a diversity of food cultures. Benoît echoed this formulation in The Canadiana Cookbook (1970), which dedicated a chapter to each province and territory of the country. Benoît wrote of the schnitzel made by Ontarian Mennonites and Scots fish cooked by Nova Scotians. She included the quintessential dish of Québec, tourtière, a meat pie eaten since the early days of New France, and instructions for cooking lobster from the province’s Indigenous Kanien’kehá:ka people. As Benoît saw it, longstanding marriages of ethnicity and distinct Canadian lands and waters lay at the heart of the nation’s cuisine. However, her national menu also incorporated the food of more recent immigrants.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Benoît regularly appeared on CBC’s afternoon talk show Take 30. She cooked Peking duck with host Adrienne Clarkson (a Chinese Canadian celebrity journalist later to become Governor General), and made a borscht recipe from the mother of the show’s other host, actor Paul Soles, whose Jewish family had immigrated from Eastern Europe. Benoît’s forays into ethnic cuisines may appear tokenistic given the dominance of English and French traditions in her cooking, but they also reflect a burgeoning appreciation of multiculturalism, a concept officially adopted by the Canadian federal government in 1971. By dedicating TV segments to Chinese and Jewish dishes, she legitimized them as part of the national cuisine.

Yet Benoît’s gastronationalism—which so often tied food to the land, seasons, and gendered labor—was rooted in old ways of life that seemed incompatible with a fast-paced and urbanizing society. Who had time to cook in modern Canada? Benoît was unfazed. Modern life would provide solutions even for problems of its own invention.

Madame’s Microwave Futurisms

At the age of 70, the grande dame of Canadian cooking set out to future-proof the country’s culinary traditions. True to form, she turned to technology. The microwave, she believed, was the natural successor to the litany of cooking appliances she had witnessed during her lifetime.

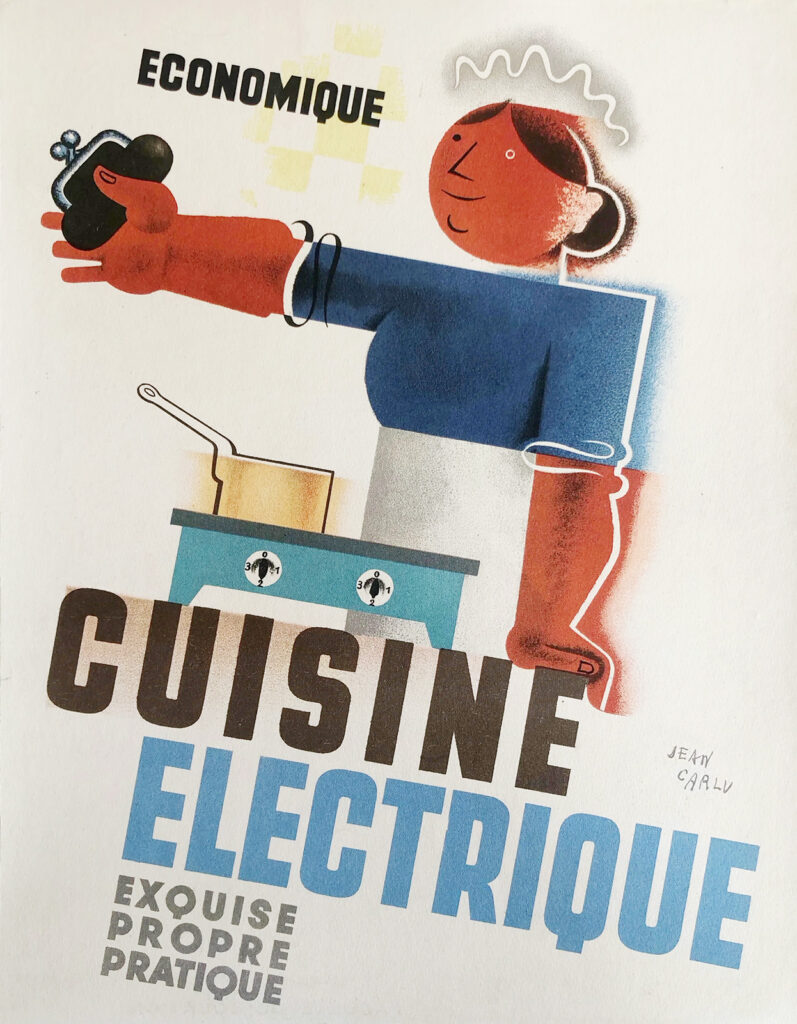

“I grew up with a wood stove,” she wrote. “Then came the gas stove, with its coin-operated metre. . . . And then one day, the electric stove made its appearance. Another miracle! But we had seen nothing yet.”

The Radarange’s invention in 1945 kicked off a race to build a less cumbersome unit that could fit on a kitchen countertop. Raytheon introduced a microwave for commercial kitchens in 1954 and delivered a scaled-down machine for home use in 1967. By then Panasonic’s domestic model had already been on the market for a year. The machine looked every part a small oven, including a fold-down door and knobs above. It would take a few years for Canadian households to adopt the device, but its introduction was emblematic of the technological innovations that flooded midcentury Canada’s consumer market.

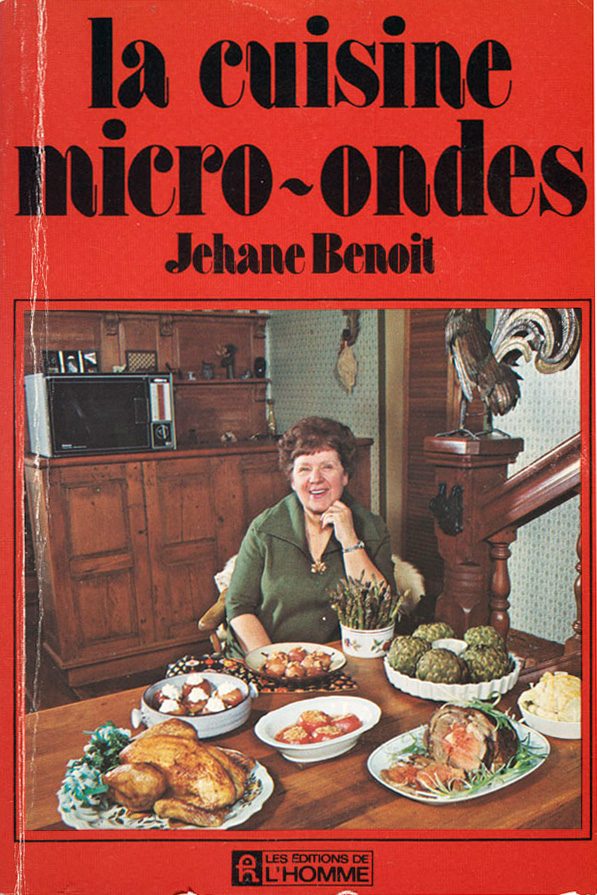

For Benoît, the microwave epitomized all the virtues of modern convenience and food science. “It was the first time I had an oven that applies all the food chemistry data,” she told Radio-Canada in 1975. Madame Benoît’s Microwave Cook Book, published the same year, explained the science behind microwave cooking. The microwave created rapid vibrations in the water molecules of food, she explained, causing it to cook quickly. The “degree of moisture,” or amount of water in a food, determined how quickly it heated.

She, like its inventors, envisioned the microwave not as a supplement but as a replacement for gas and electric ovens. She therefore used it to cook multicourse meals, from appetizers to desserts.

The microwave’s radically different cooking method required radical modifications to her recipes. Since each ingredient in a dish cooked in different times according to its water content, Benoît devised an involved process of heating, adding more ingredients, and reheating in an order determined by ingredients’ moisture content and density. For Veau dans le chaudron, “an Old Québec recipe,” the reader was instructed to first heat the oil, then the veal, and finally the spices and potatoes. Leftover juice from the veal was to be further microwaved until it turned into gravy. With the touch of a few buttons, the recipe produced in 20 minutes a veal roast that would ordinarily take well over an hour.

Such efficiency was driving the microwave’s appeal, Benoît claimed. “The younger generation is more and more going into the kitchen looking for shortcuts,” she remarked in one interview; even her own granddaughter had asked for a microwave as a wedding gift. Moreover, Benoît was adamant that microwaves brought out foods’ “true flavor” better than traditional cooking methods.

Armed with Madame’s Microwave Cook Book, women could turn out healthy and previously labor-intensive dishes more quickly and efficiently than ever before. Its time-saving abilities moved Canadian cuisine into the future by allowing “working couples” to make a traditional Canadian meal in minutes, or so Benoît claimed. Yet like many midcentury appliances that promised to ease the burden of domestic labor, the microwave’s promoters envisioned uses with the opposite effect. Its efficiency was not meant to help women claw back time for themselves, but rather to help them serve more elaborate meals with the few waking hours they had after returning from the office.

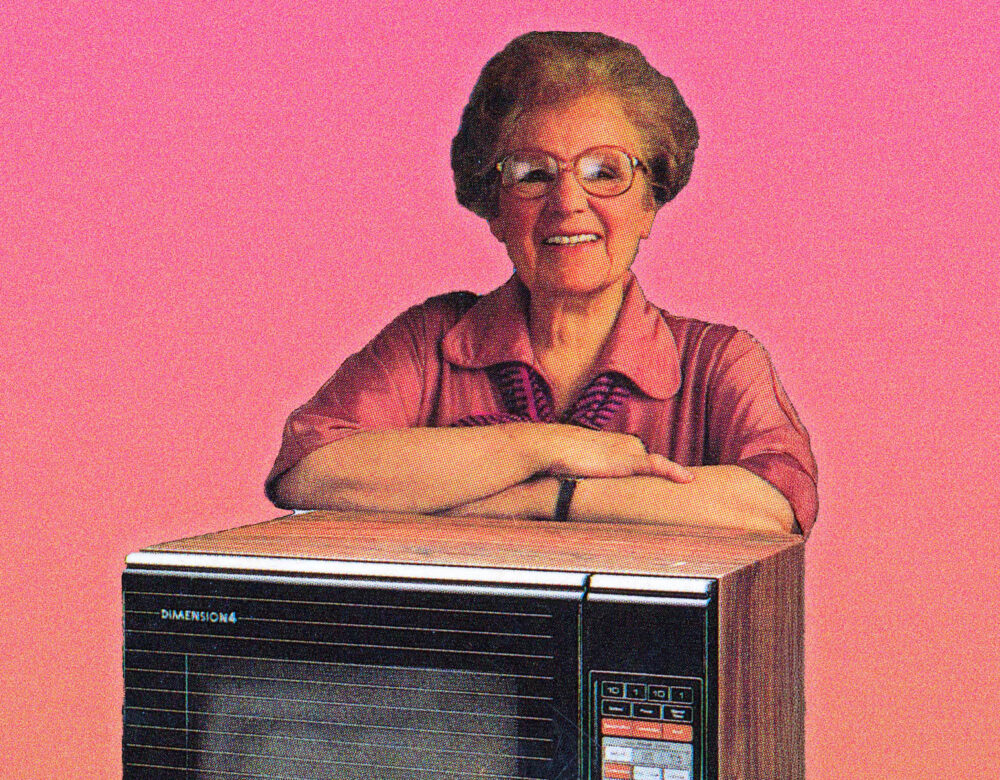

In the late 1970s Benoît became a spokesperson for Panasonic microwaves. In one appearance, a 1986 TV commercial for the Genius Dimension 4, a camera pans through the busy dining room of an upscale French restaurant. When the viewer sees the kitchen, it is inexplicably empty, its ovens abandoned. Instead, this haute cuisine is produced entirely in microwaves, cooked by a waiter at the press of a button.

With this marvelous machine, the ad implied, women could now turn out Michelin star dishes at home. At the same time it suggested that a microwave allowed any man to compete with the male-dominated world of professional chefs. Benoît echoed this sentiment.

Though she frequently touted the value of women cooking in the home, it was not because she thought men were incompetent cooks. Rather, she saw daily cooking as labor outside of their domain. It was a woman’s obligation. “Men cook mainly for pleasure,” she opined, “because they like to eat.” But now that the microwave had made cooking a pleasure, rather than a labor, even the most unlikely demographic—young, single men—might start cooking for themselves.

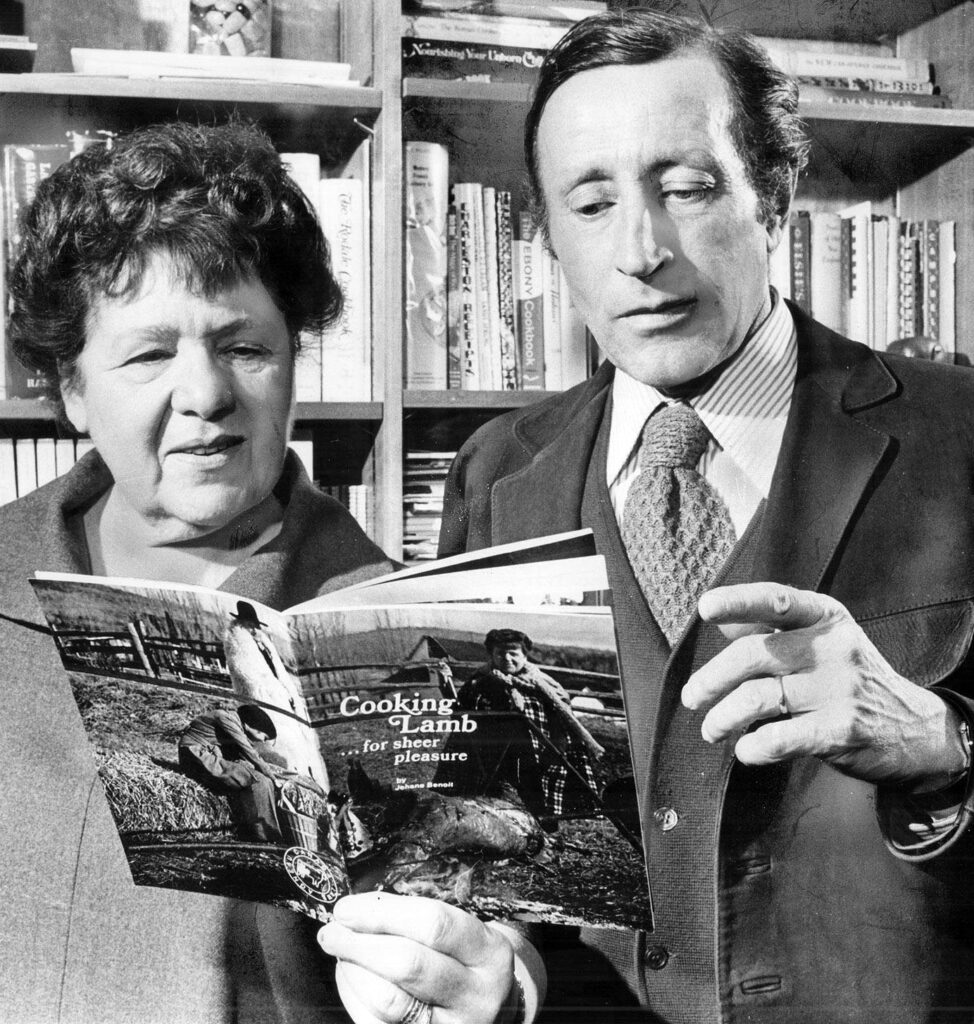

To prove her point, in 1978 Madame Benoît went on Paul Soles’s late-night talk show, Canada After Dark. The other guest that night was Québec pop sensation René Simard. Gesturing to a pile of hamburger patties, Benoît looked toward the 17-year-old and enticed the audience with the revelation that he was going to cook them using Panasonic’s Genius microwave, equipped with auto-sensors to detect food’s perfect cooking time.

“It won’t be good!” protested the young celebrity, to which Benoît responded, “It will be good, because you don’t have to do anything. That’s the genius,” gleaming at her pun. Soles’s interjection—“Years ago, it was mix, mix, fuss”—recalled the outmoded labor of cookery. “Oh, we don’t do that anymore!” exclaimed Madame Benoît. (She skips past the trip to the butcher to buy steak, grinding the meat, and all the mixing and fussing she had done to make those perfect patties.)

Women viewers saw that there would be no more standing over the stove dodging spattering oil. Rather, the raw hamburgers entered the metal box and, like magic, emerged cooked. The invisibility of Benoît’s labor before the show created the illusion that it was a relic of the past and that now even a young heartthrob would cook for himself.

In the late 1980s, Benoît published her book series Encyclopedia of Microwave Cooking. Her experiments with the device left her convinced that the only thing the microwave lacked was the ability to make food brown and crispy. Her tourtière, she admitted, never turned out quite right in the microwave. She addressed these concerns with Panasonic, which began working on a solution. In September 1987 the company unveiled a new unit, the Madame Grille: a combination microwave and convection oven with an insertable grill attachment for browning.

Madame Benoît would pass away two months later. By the end of her life, she owned multiple microwaves and envisioned kitchens of tomorrow as long counters with nothing but electrical outlets. Benoît even saw microwaves, free of woodsmoke and gas pollutants, as the eco-conscious solution to novel environmental concerns in the public discourse.

Nonetheless, it was Julia Child’s view of the microwave that most women would come to share. “I wouldn’t be without my microwave oven,” Child wrote in her book The Way to Cook in 1989, “but I rarely use it for real cooking.” The microwave never replaced the gas or electric stove in expensive restaurants, or even the home. Rather, as women re-entered the workforce en masse at the close of the 20th century, it found its place in the hierarchy of kitchen appliances—as the quick way to reheat leftovers or cook a premade frozen meal after a long day at work, or, as its inventor discovered early on, as a cool way to make popcorn.

Some Canadian grandmothers bake tourtière pies. Not Jane Litt. Jane was a good cook, but most of the time she would stand in the kitchen only half-aware of what she had on the stove, too busy quoting Milton or expounding on democracy as first conceived by ancient Greeks. Jane would warm store-bought tourtières in the oven, agreeing with Madame Benoît that microwaves could never make them properly crisp. She used the microwave sparingly, primarily to reheat her tea. She and Marilyn would remain friends for life. As they got older, they reminisced about their school days together, and their old friend Monique.

And what of their lunchtime outings? “I certainly have happy memories about it all,” she told me, while recounting the story of Canada’s very own, modern-traditionalist, Canadian-nationalist, French Canadian chef.