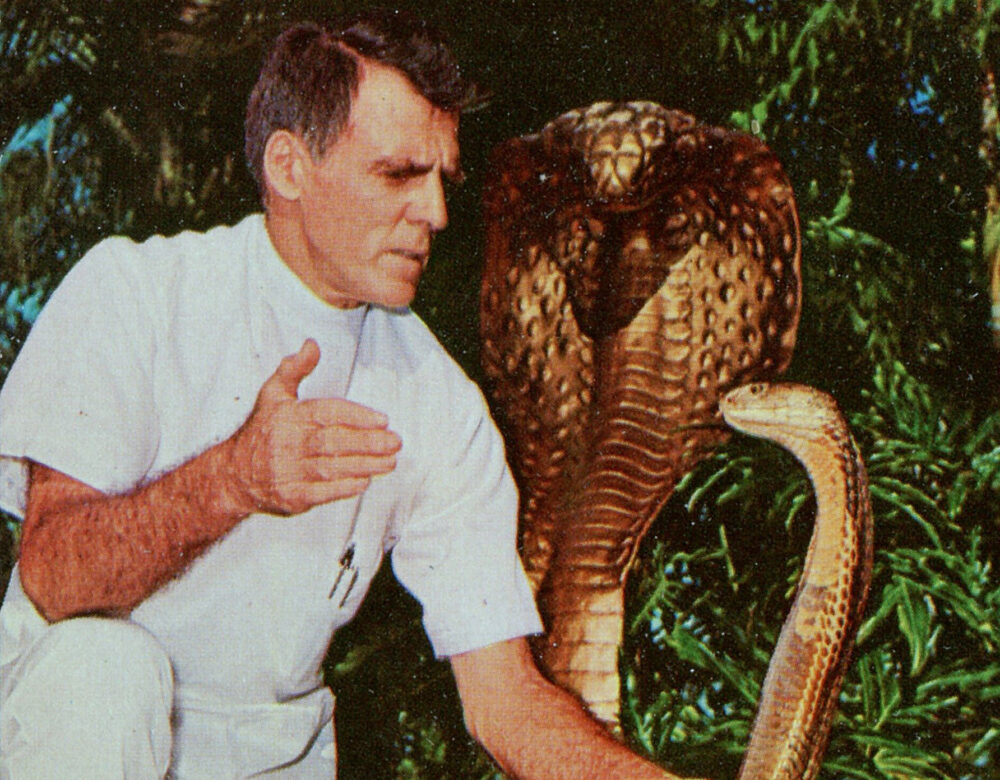

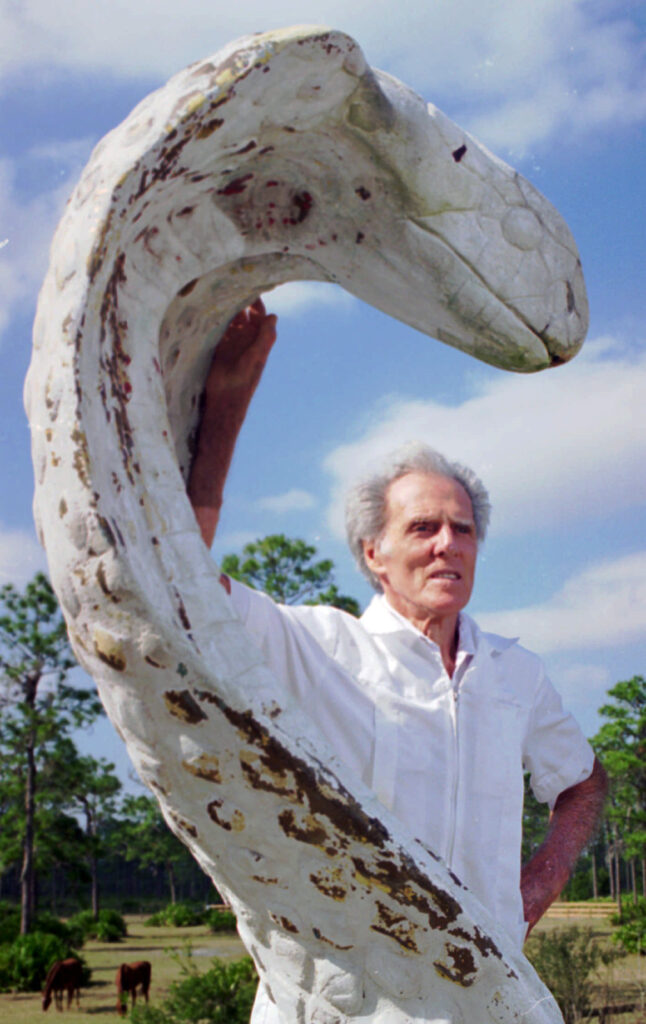

Every Sunday for more than 30 years, Bill Haast would release one of his king cobras on his lawn so that he could “fence” with it.

Haast would hold his imposing but often reluctant opponent by the tail when it tried to slither off, sometimes prodding it with a metal hook to get it riled. When a snake finally reared up to face him, bobbing its head with menace, Haast would use one bare hand to distract the irate ophidian until he found an opening to lunge and seize its head with the other.

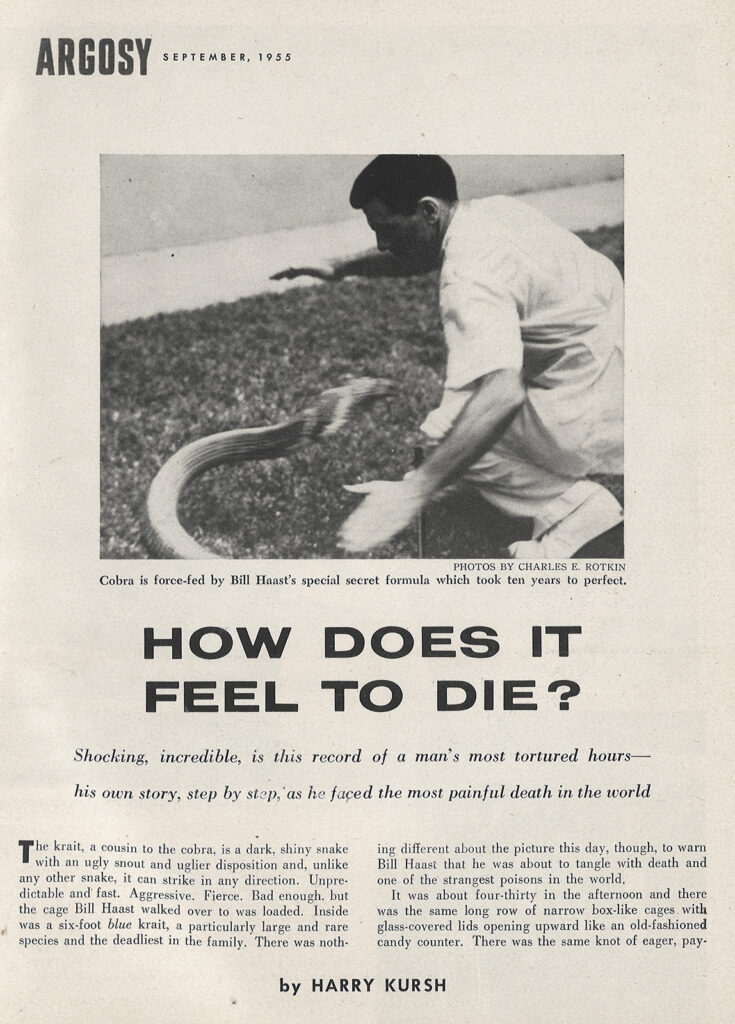

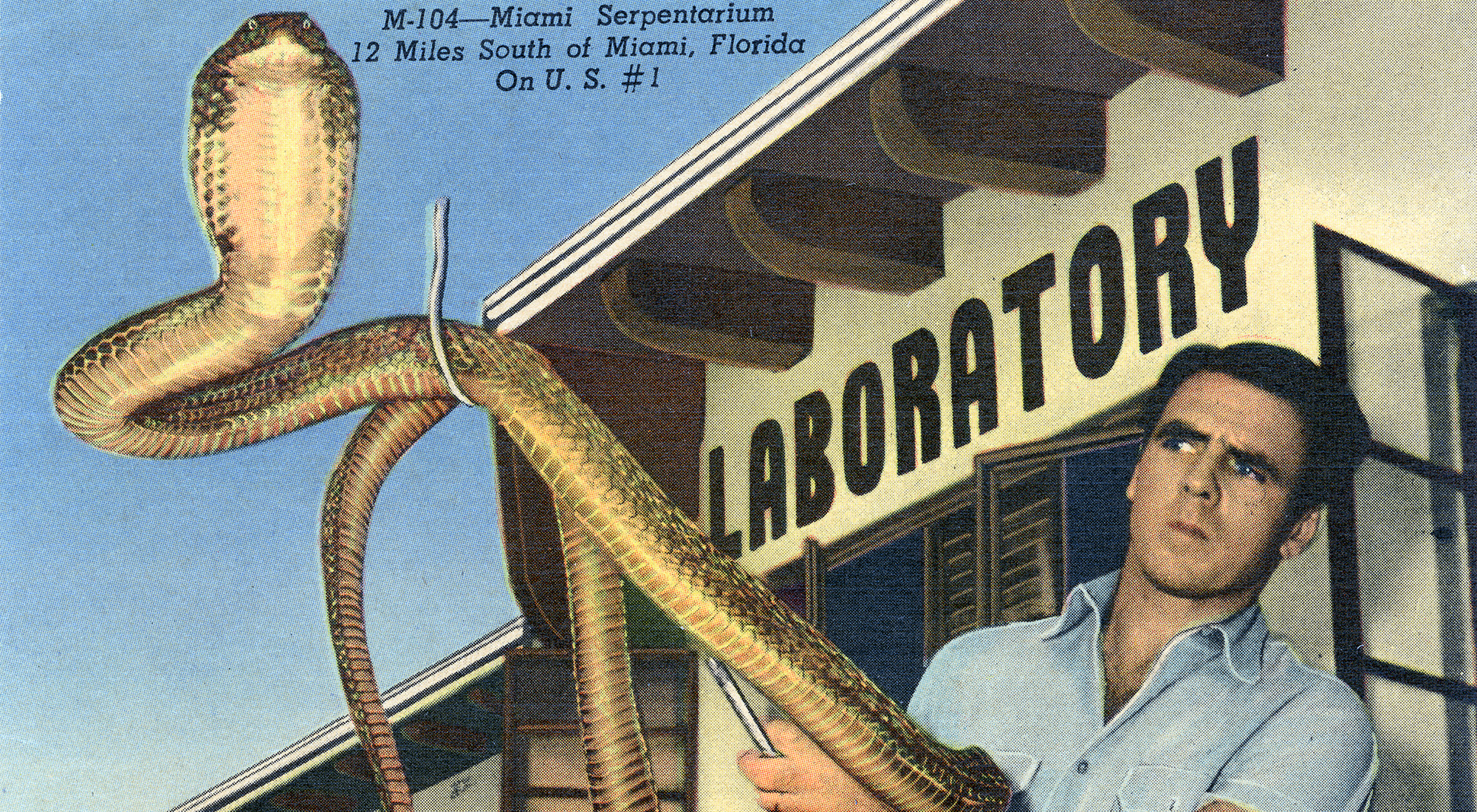

Most Sundays, he would repeat the process twice more with a new snake and a new crowd of spectators standing just feet away from the ordeal. This was, after all, one of the main draws of his Miami Serpentarium, once touted as the nation’s largest snake enclosure and a fixture among Florida’s storied roadside attractions. From 1948 to 1984, Haast offered daily tours of his menagerie and a chance to see him coax venom from some of the world’s most dangerous serpents.

“For a kid growing up among the gators and moccasins of rural South Florida, Bill Haast was a hero, and a trip to the Serpentarium was a pilgrimage,” wrote author Carl Hiaasen, an early architect of modern “Florida man” memes, in 1989. That’s how most visitors and locals remember Haast—as the Snake Man, an eccentric entertainer.

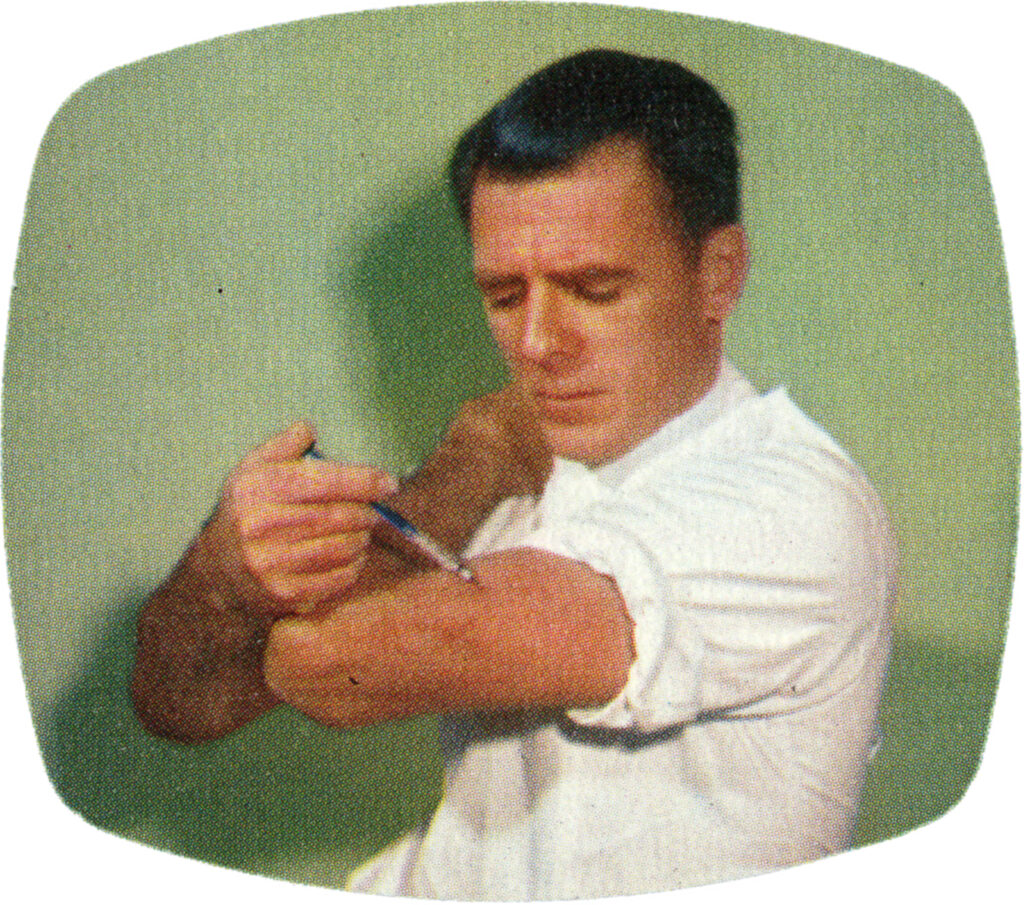

The wider public knew him as the guy who appeared on TV with everyone from Mike Douglas to Jack Hanna to talk about snakes, venom collection, and his considerable experience with bites. He made the papers periodically for his habit of injecting himself with small doses of venom to build up protection against a unique occupational hazard and for offering his supposedly antibody-rich blood as a treatment for people suffering from rare snake bites.

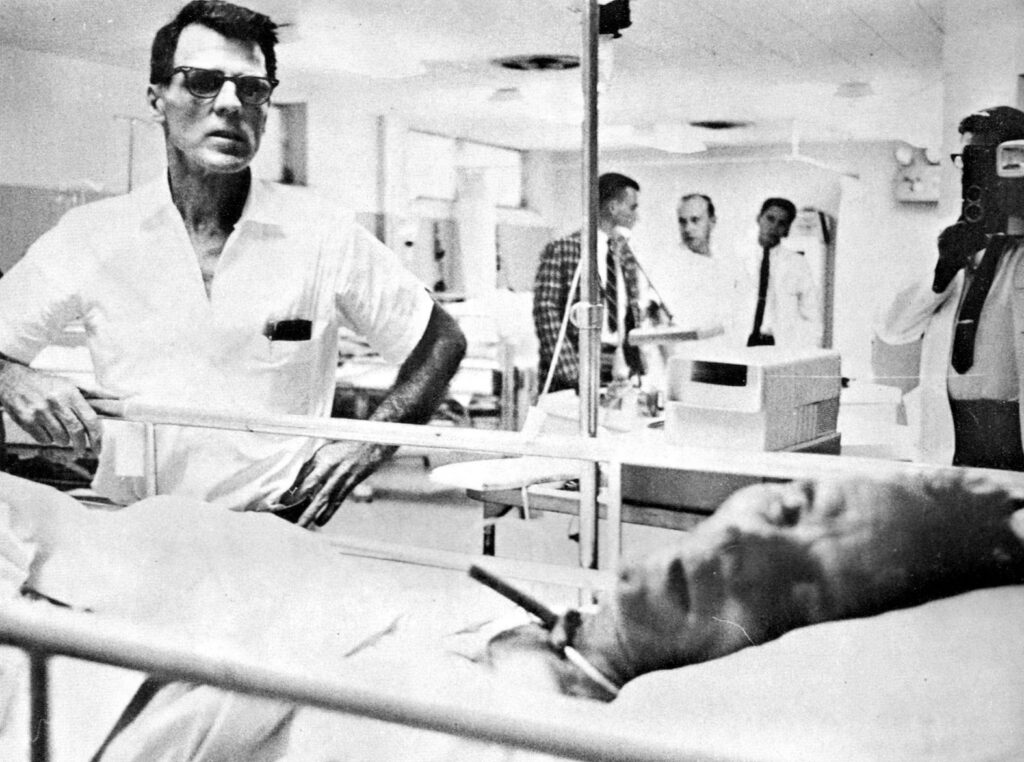

Clip from an Eastern Air Lines promotional film, Florida’s East Coast Holiday, ca. 1960.

Florida Memory

When he died in 2011, most of Haast’s many obituaries led with the number of dangerous strikes he himself survived—at least 172 by his wife’s count—before succumbing to old age at 100. Only a few explained his real aim: revolutionizing the study of snake venom.

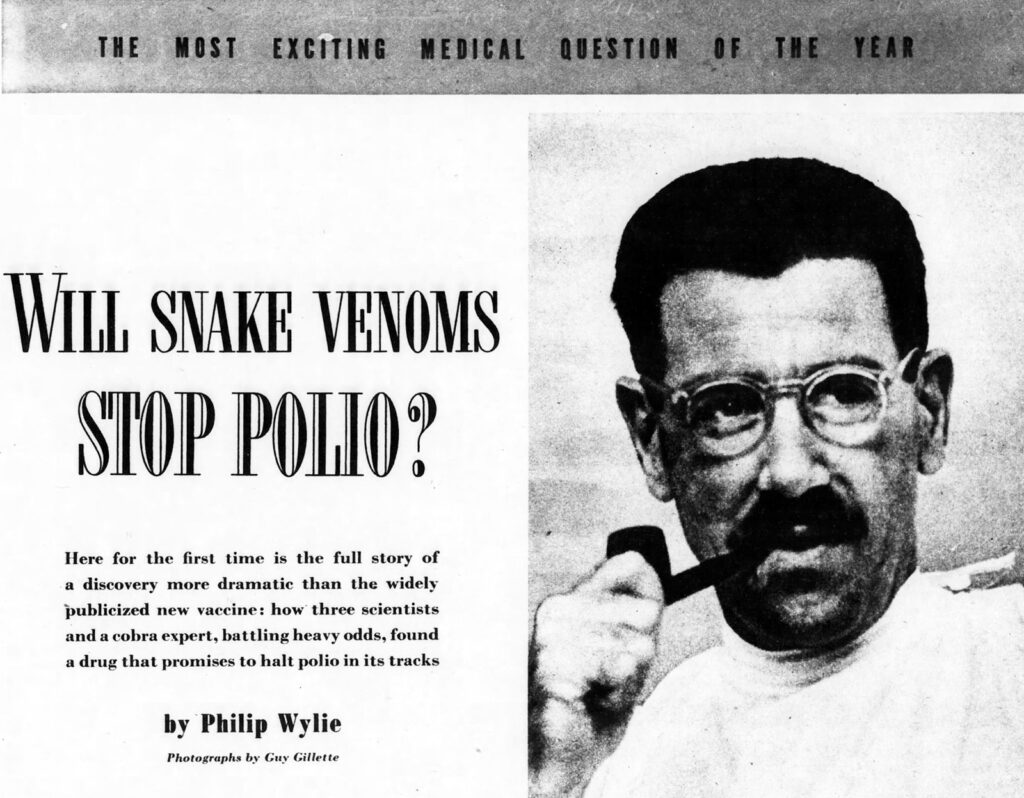

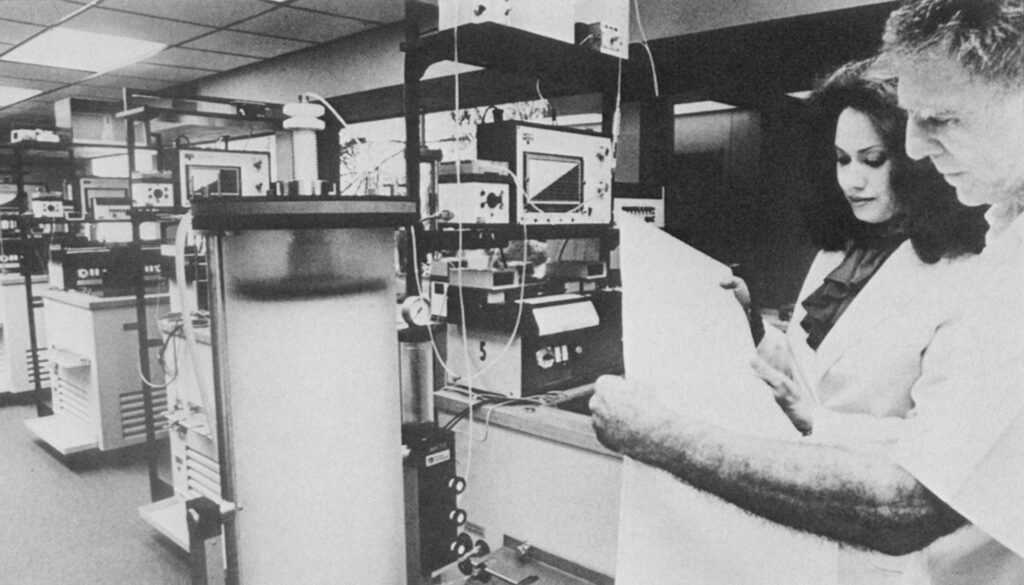

The lab he operated within the Serpentarium delivered a steady and abundant source of high-quality venom to drugmakers and researchers around the world. Tourist shows and media spots, he claimed, were just ways to subsidize that work. Even the most detailed memorials failed to capture the full scope of his influence on herpetology and venom research in the United States. Many in these fields still treat him with reverence.

“Like the pope is to the Catholic Church, he’s like that to the venomous herp community,” recalls Ray “Cobraman” Hunter, a former Serpentarium employee-turned-lifelong-friend and now a prominent snake handler in his own right.

While venerated by many, Haast was far from infallible. He left a complicated scientific record, especially when it came to his work on venom’s medicinal potential. He spent decades developing—and tied his legacy to—venom-based wonder drugs he claimed could treat some of life’s most intractable diseases. His critics charged that Haast’s pursuit of this dream endangered ill and desperate people.

As his friend and physician, Ben Sheppard, once remarked, “Bill Haast really believes that snake venom cures everything from ingrown toenails to dandruff.”